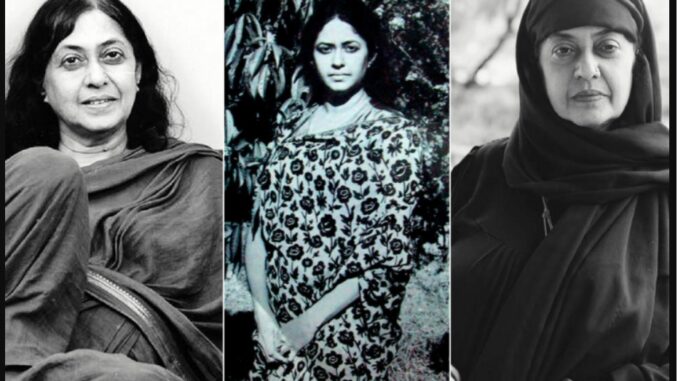

Madhavikutty/Kamala Das/Kamala Surayya. March 31 1934-May 31 2009

Paul Zacharia.

A Prelude

M

adhavikutty, aka Kamala Das, aka Kamla Surayya, (1934 -2009) is one of the greatest names in 20th century Malayalam fiction and a prime-mover of modernity, transforming language, craft and the modes of engagement with emotion and feeling. She brought to her written and spoken word a refreshing freedom and originality that made inroads into the realist/progressive idiom in vogue then. Spontaneity marked her craft – and life. Her unsentimental style shone with a deep humanity. She also wrote stunning poems in English during the period Indo-English poetry was emerging as a force to reckon with.

Apart from her writing which was wide-ranging and celebrated, Madhavikutty’s outspoken social interventions made her a household name – hated by many, loved by many, many more. At a time when feminism was much more despised than it is today in Kerala’s morbidly male society, she spoke out for dignity, equality and freedom for women and was jeered and insulted. She laughed at the hypocrisies of Kerala’s socio-political orthodoxies and lashed out at the forces of masculine-feudal decadence, infuriating their religion-and-caste-centric strongholds.

She became a near-outcaste when her explicitly narrated autobiography burst upon the die-hard conservatives of Kerala in the 1960’s. Her final act of revolt was her conversion to Islam in 1999 when she was in her seventies. P. Parameswaran, the top ideologue of the RSS in Kerala then, made an interesting comment when he heard the news. He exclaimed: ‘God save Islam!’ It points – though he didn’t intend it – to Madhavikutty’s utterly free, subversive and irrepressible spirit. She was a threat to all narrow-mindedness – including Parameswaran’s.

Upon her death there was much commotion about the decision to bury her – the daughter of one of the pre-eminent Nair families of Kerala –in a Moslem cemetery according to Islamic rites. Madhavikutty sleeps in the grassy grave yard of the Palayam Juma Masjid in Thiruvananthapuram. I was at the funeral. I, as a writer, owe a lot to her; and she was a wonderful friend.

Madhavikutty Returns to the Soil

W

e never knew all these years that the Palayam Juma masjid in Thiruvananthapuram had such a lovely garden for the dead at its backyard. Who would have thought that the dead had such a shady and serene enclave in the heart of the city’s clamor and rush? I, for one, didn’t even know that the Moslems had a graveyard at all. What was I thinking, then? That they didn’t die? Perhaps we live completely oblivious of how others live – and die. It was so good of Madhavikutty a.k.a. Kamala Das a. k. a. Kamala Surayya to travel in her death all the way from Pune to Thiruvananthapuram to reveal to us these little neighborhood secrets.

When I go inside I am dwarfed by the giant mahagonys rising into the sky, their branches intertwining to make a shamiana of leaves and patches of clouds and blue skies. The sun throws throbbing windows of light and shadow on the soft rain-soaked ground that seems ready for digging and planting. Perhaps things would have been somewhat like this if Madhavikutty had decided to lay herself down in the leafy and shady yard of her ancestral home at Punnayoorkulam that she had celebrated so lyrically and consistently.

Across the road, a few hundred feet away is the tall steeple of the catholic church, a statue of Jesus surveying the city from there. To the left of the mosque’s gate is the Hindu Ganesha temple, sharing the same compound wall. From inside the gravveyard I am surprised to see yet another church tower looking in from the back. My friend reminds me it is the Malankara Orthodox church next door. Madhavikutty is in good company. Ganesha, Allah and Jesus have taken positions around her. Though she had no use for them, she had a great time talking about them as the fancy took her.

![]()

We had wondered if we would be allowed in for the funeral because mosques are considered out of bounds for non-Moslems. But I reminded myself that neither had I ever checked with a mosque if I could go in. Now we are graciously led inside and taken to the spot under the trees where a wide, spacious grave has been dug. Being familiar with Christian burials I can see this grave is different. Christians have deep, frightening pits into which the coffin has to be lowered with the help of ropes. This is almost shallow and looks manicured and inviting. Ready for planting a sapling.

Suddenly the media rushes in, followed by the politicians and their hangers-on. The grave is now hidden from view by the crowd. It is announced that Madhavikutty’s body has been brought to the mosque for prayers. A cameraman climbs the tree I am leaning on with a mumbled apology. I keep a wary eye for falling bodies. And now Madhavikutty arrives, her bier carried on the shoulders of pall-bearers, preceded and followed by the usual stampede. How she would have loved all this! She enjoyed being celebrated, like a baby enjoying its bath.

As I brace myself against the tree, she is gone. I can hear prayers. And then the policemen go through convoluted drills and fire their guns in an official salute, shocking the birds on the trees. They scream and fly off. Some people had warned of riots and rebellion if she, a Hindu, were to be interred in a mosque. These gunshots are the only violence around. And that was that. One of India’s most courageous and gifted women had returned to the soil. Soil, fortunately, has no religion.

: This first appeared in The New Indian Express June 9 2009

*****

Paul Zacharia is the author of more than 50 books ranging across literary genres including screenplays, recognized and awarded for his contribution to Malayalam literature. A Secret History of Compassion is his first novel and in English.

Paul Zacharia in The Beacon

Leave a Reply