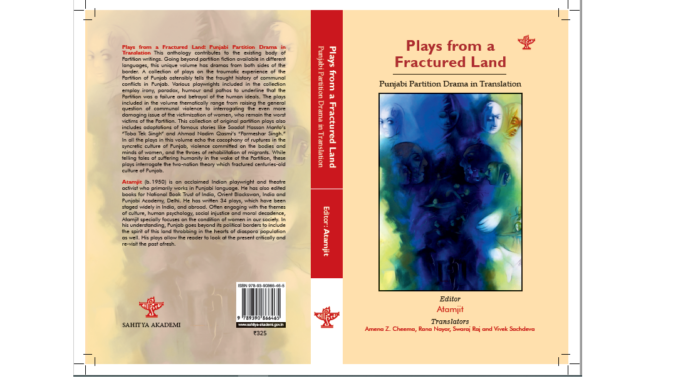

Plays from a Fractured Land. Punjabi Partition Drama in Translation. Editor Atamjit. Translators: Vivek Sachdeva, Swaraj Raj, Rana Nayar and Ameena Cheema. Sahitya Akademy 2021. Pages 316

“Lovers of literature, and college students everywhere, will be glad that Plays from a Fractured Land is out. The book’s dramas are hardly tranquil, for they deal with the gore, loss, pain, guilt, shame, and shock of the 1947 Partition, which sliced the vast Punjab province into two, destroyed a great many lives, and uprooted even more. However, these plays are bound to arouse our interest, for they capture the irresolvable yet stirring dilemmas faced in 1947 by Punjab’s women and men, who were Muslim, Sikh or Hindu, yes, but also human beings, like anyone else”.-Rajmohan Gandhi

“Atamjit Singh, an eminent playwright, has edited an invaluable collection of contemporary Punjabi plays about India’s Partition. Translated into English and written from both sides of the border, these plays speak with sorrow about the sudden destruction of small bastis and ordinary communities with shared cultural life-histories.

The Bhayanak Rasa, the passion of fear and terror that moves these playwrights is not only a result of memories of past atrocities, but also of the continuing acts of lynch mobs whose hearts smolder with religious hate and minds are haunted by imaginary monsters. One must listen to these playwrights as one listens to pleas of mercy, pity, peace and love.”–Alok Bhalla

**

Atamjit

Punjabi Partition Drama

(Excerpts from the Introduction )

T

he intertwinement of art and reality is something that is always a given in any discussion on how art relates to reality. Since reality is understood to predate art, and also because of its putative veridic nature, history is often accorded precedence over art. Art is generally thought to be fictive reality. But no thinker has ever denied the fact that despite history antedating art, the relationship between history and art is not merely a one-to-one correspondence with history providing only the facts and art using these facts as its raw material to fashion a beautiful artifact by infusing emotions into it. The mediation of a literary author plays an important role in this transformation.

The tangled relationship of literature and history was an issue that even Aristotle also grappled with in his Poetics, and in trying to establish that poetry is superior to history, he suggested that the statements of history are in the nature of particulars whereas those of poetry are in the nature of universals, thus denying history any claim to universality. But somehow, those who value history for its truth-claims tend to undervalue literature for its reliance on imagination. Conversely, there are many thinkers who suggest that history itself is replete with fiction as it is also a selection made from an entire panorama by historians according to their own bent of mind. Such a position draws vigour from Kantian idea of unknowability of the “thing in itself”. Apart from this, now historiography is also understood as a textual enterprise, a linguistic construct that is subject to a similar kind of deconstructive reading as any other literary text is.

The fact is that the denial of truth-value either to history or to literature indicates positions that are binarist and hence problematic. We need to move away from this binarism that tends to privilege one over the other. As it is, many contemporary thinkers such as Hayden White and Keith Jenkins go beyond these binaries and in doing so, they suggest that the boundaries between literature and history are extremely porous and the imbrication of history and literature makes it difficult to tell the two apart from each other.

The reality of bifurcation of India in 1947 into two nations was extremely tragic. The task of drawing the boundaries of the two nations was given to Cryril Radcliffe. He was given only five weeks to demarcate the border. He had no idea whatever of the culture of the land, its geography, religious sensibilities of the peoples, social circumstances, and political realities. At first the British rulers had decided to free India in June 1948, but owing to their own compulsions, they advanced the date to 15th August, 1947. The arrangements they made for the Partition were half-baked. The communal fire that started in West Bengal in the wake of the impending Partition took the form of a terrifying conflagration in Punjab. About twelve to eighteen lakh people lost their lives in the violence that accompanied the Partition. According to some estimates, about fifteen million people migrated from one country to another and about ten million of these migrants were from Punjab. Caravans of migrants were attacked on both the sides and countless people were put to death. Trains of migrants were stopped and people travelling in them were slaughtered. Many villages were attacked in a systematic, planned manner. About seventy-five thousand women were raped. Patients admitted to hospitals and mental asylums were set free. These facts are well documented in history, but where those patients went and how, history will perhaps never be able to tell us. It is literature that gives voice to the sufferings of such people. How those who were once land owners in West Punjab had to start their lives anew from a scratch in the arid fields of East Punjab, it is literature only that narrates their travails. We have no account of women who either committed suicide to save their honour or were killed by their own people. We have no idea how many women were abducted but continued living courageously in a different land and in a different culture and religion. We do not know the plight of many such women against whom the circumstances conspired to separate from their families and they had to start their families anew. And among those who did start life afresh, how they grappled with the situations when they happened to meet their first family from whom they were separated, we have no idea. History narrates the story of a divided nation, whereas literature gives us the story of divided hearts. History will never tell about those children who were lost during the exodus. Literature is concerned about them also. History tells us how ordinary, innocent people hurtled into the mass madness and lost their sanity, but is silent about those who were actually insane.

Urvashi Butalia, in her acclaimed text, The Other Side of Silence (1998) foregrounds the silence of history in these words: “As an historical event, Partition, for example, has ramifications that reach far beyond 1947, yet historical records make little mention of the dislocation of people’s lives, the strategies they used to cope with loss, trauma, pain and violence. Why have historians been reluctant to address these? Are these questions of no use to history at all?” In this text, she has recorded the testimonies of those who were witnesses to the Partition mayhem. Veena Das, Ritu Menon and Kamla Bhasin have also made commendable contributions in this regard. Sukeshi Kamra, in her text Bearing Witness: Partition, Independence, End of the Raj (2008) focusses mainly on the ‘silence’ of the survivors of the Partition tragedy. According to her, what needs to have been said about the Partition was never said. Perhaps the people who were traumatized wanted to forget this catastrophe forever because of the sense of shame, guilt, trauma and extremely painful memories of toxic patriarchal violence associated with it.

According to Anjali Roy Gera, official versions of history are incapable of throwing light on the social, cultural and economic life of common people. She argues in her very recent book Memories and Postmemories of Partition of India (2020) that the erasures and omissions of the sanitized official histories come to light through personal testimonies and eye witness accounts of the survivors. In a scathing criticism of the official versions of Partition history, she alleges that “the master narrative of Indian Independence could have been produced by the Indian state only through the repression of gendered, classed, casteist, sectarian, regionalist stories of Partition that interrupt triumphalist nationalist history through their testifying to its unspeakable violence and suffering.” Hence the gaping lacunae, the unsaids of history can only be filled by recovering the lost stories of ordinary people displaced and deracinated by the Partition, the stories that have been either completely omitted from the official history or are confined to its footnotes only.

Memory, despite its known fallibility, corporeality, and selectivity can still be relied upon to yield an archive of microhistories which can fill the gaps and elisions of nationalist histories of India’s Partition. It is in this context that literature has an important role to play. Many literary authors who have written about the Partition have had a personal experience of the tragedy that accompanied India’s Independence. Being authors, they were not even hesitant to speak. And then there are those authors also who did not experience the tragedy first hand, but they wrote plays based on true narratives penned by other authors and also on oral testimonies of the sufferers. In this way, the lived tragedy of Partition has had an unmistakeable bearing, directly or indirectly, on the Punjabi Partition drama.

Naturally, all the playwrights selected the incidents about which they wrote according to their own ideological predilections, though imagining and reimagining the actual incidents, and any additions or subtractions thereof were necessitated by the imperatives of creative structuring of the subject matter to suit the aesthetics of the stage. This is how the stark, chaotic reality is given an aesthetically beautiful structure by blending it with fiction and then fixing it within certain fictional limits. The tragic reality of the Partition and its wounds are, however, never occluded with aesthetic coverture; the idea being neither to scour the old and partially healed wounds, nor to gloss over them, but to engage with what had happened and how to prevent such a tragedy from repeating itself. In this context, it would be worthwhile to refer to the work of Dori Laub, a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who himself is a survivor of the Holocaust. His most important contribution to Holocaust trauma studies is the Holocaust Survivors Film Project he undertook in collaboration with the documentary filmmaker and television producer Laurel Vlock. The documentary they prepared has interviews with thousands of Holocaust survivors. Laub is of the view that the oral testimonies of the survivors need no verification because their survival itself is a proof of the horrors of the Holocaust.

The Italian historian and scholar of culture Alessandro Portelli attaches great importance to oral history. In his book The Death of Luigi Trastuli and Other Stories: Form and Meaning in Oral History (1991), he accepts the importance of memory in inter-generational transfer of oral history. According to him, the utility of oral sources for historians lies not so much in their “ability to preserve the past, as in the very changes wrought by memory. These changes reveal the narrators’ efforts to make sense of the past and give a form to their lives …” In a way, in view of the immensity of the Partition tragedy, the oral testimonies given a coherent structure in the form of literature, can be understood in Partolli’s sense as having a lot of value in our trying to come to grips with the tragic circumstances in which horrors piled up on horror tend to preclude the very possibility of comprehending them. Apart from this, the literature based on oral testimonies does give a voice to the silences and unsaids of history; and in this sense, it is history from below.

*

Most of the other states in our country are unaware of the extent to which the Partition impacted life in Bengal and Punjab. This momentous event changed the whole tenor of life in Punjab in particular. However, in one of his lectures, Girish Karnad (1938-2019) remarked that the Partition of India did not bring about a significant change in the country. Although, Karnad made this remark in a different context, but no Punjabi or a Bengali can ever make such a claim or believe it. When Pakistan was carved out of India, no other state of the country was bifurcated except Punjab and Bengal. Areas like Sind and North West Frontier Province were transferred to Pakistan in toto.

The Partition violence lacerated the psyche of the Punjabis so much that till date Punjabi authors are writing poems, stories, novels and plays about it. Amrita Pritam’s Ajj Akhan Waris Shah Nu (I ask unto Waris Shah), written in the wake of the Partition, stands out as one of the most poignant poems that portrays the collective agony of the Punjabi women who were publicly disgraced. In fact, scores of anthologies of literary writings dealing with the Partition are available in Punjabi language.

However, the present is what we have with us. We cannot wish away our past but at the same time, we cannot allow the tragic past to cast its dark shadow on the present and ruin our future also in doing so. That Pakistan is a separate nation is a fact, which cannot be refuted or undone. But somehow, our two nations have cultivated a long standing enmity rather than friendship. Pakistani Panjabi poet Ahmed Salim’s (Born 1945) Wahga sums up the tangled and troubled relationship of the two countries:

There are flowers betwixt us

But the wall is still a wall

Even if of flowers.

And there are letters we exchanged

That awaken the pain of separation.

We have tears

That cloud us in each other’s eyes.

And there’s pain

Spread betwixt us like a vast expanse of land.

And there’s love among us

That unconnects one into two.

Wherefore my vile beloved, I wish

To enfold you in my arms, to hate you and cry.

*

More than a hundred plays have been written about the Partition; a few by those who had experienced the tragedy first hand and their writings are related directly to their own experiences. Gurdial Singh Khosla (1912-1995) did theatre before the Partition in Lahore. His plays deal with the problems faced by Partition refugees. Although Kartar Singh Duggal (1917-2012) was basically a story writer, but having been associated with the All India Radio for twenty-four years (1942-1966), writing radio plays and enacting them was a part of his calling as well as his avocation. In his play Diva Bujh Geya (The Lamp was Blown Out), he portrays the horror of Partition, problems of the refugees and patriotism of the Kashmiris. His play Mittha Pani (Sweet Water) deals with countless problems of rehabilitation faced by the refugees, one of them being that they do not find the water of this side sweet.

Harcharan Singh (1915-2006) migrated to Delhi from Lahore after the Partition. In his Tera Ghar Mera Ghar (Your House is My House), he depicts how some vested interests had tried to drive a wedge between Hindus and Sikhs after the Partition. His short play Hethle Utte (The Down are Up) portrays the economic impact of the Partition turmoil on the lives of people. Those who were placed on the lower rung of the socioeconomic order before the Partition acquired huge property after migrating to India, while those migrants who were well off in Pakistan did not acquire property as they waited for the things to settle down so that they could go back to their previous jobs. Apart from these, Chaudhry is Harcharan Singh’s another important play dealing with Partition. It narrates the story of a Muslim father who wants to migrate to Pakistan safely with his two unmarried daughters. Chaudhry, the eponymous protagonist of the play, helped many others also along with this Muslim. As the play unfolds, we come to know that the Chaudhry is also waiting for someone to safely send to India his daughters stranded in Pakistan.

Harsaran Singh’s (1929-1994) family was not willing to leave Gujjarkhan to migrate to India, but they were forced by the violence in 1947. His major play, after his few initial radio plays, was Ikk Vichari Maa (A Helpless Mother). Kapur Singh Ghuman (1927-1985) was working in Delhi when his wife walked all the way through agricultural fields from Sialkot to reach India. It was with great difficulty that Ghuman found her in a refugee camp in Delhi. Their one-year-old son died of exhaustion and thirst. She did not even let him cry lest his voice be heard by some desperado. Thus, the Partition inflicted deep wounds on Ghuman’s psyche. Although Gursharan Singh (1929-2011) came to the theatre late but he, Harsaran Singh and Ghuman were coetaneous; therefore, they had many painful memories of Partition to share with others. Roshan Lal Ahuja (1904-1990) and Amrik Singh (1921-2010) are also eye witnesses to the Partition mayhem. The surname of the film maker Sagar Sarhadi (Born 1933) alludes to the Sarhad province now in Pakistan. Davinder Daman (Born 1943) was barely four or five at the time of the Partition. But he vividly remembers till date the dead bodies and broken skulls scattered all around.

Mukh Adhyapak (Head Master) by Balwant Gargi (1916-2003) that deals with the Partition finds mention in one book only, though Gargi seems to have distanced himself from this play. Similarly, Sheela Bhatia wrote Vaadi di Goonj (Echoes of the Valley) about Kashmir, but this play is also not available. Among the other prominent Punjabi playwrights, I. C. Nanda (1882-1965), Sant Singh Sekhon (1908-1997), Sheela Bhatia (1916-2008), Gurcharan Singh Jasuja (1925) and Surjit Singh Sethi (1928-1995) did not write any play dealing with the Partition.

![]()

It is, however, very important to know the sources of inspiration of those playwrights who were born after 1947, who did not experience personally the agony of the Partition but still wrote about it. Such playwrights experienced this pain vicariously through the happenings in 1984, and also through what preceded and followed 1984. It is during this period that the spectre similar to the Partition of 1947 started raising its head in the minds of the Punjabi authors. About the play Rishteyan da ki Rakhiye Naa (No Man’s Land) written in 1981 by Atamjit, Satinder Noor says: “Atamjit (1950) creates a new text based on the story Toba Tek Singh, whose backdrop is different from that of Manto’s (1912-1955) story. The historical circumstances are also different. This is how the text acquires double signification.” In his Introduction, the author also writes: “I am indebted to Manto for his great story. But my motive is not simply to understand or clarify the meanings of Manto’s story; my intention is also to set up a dialogue with the present circumstances through the story. Present in this dialogue are Manto’s 1947, 1981 when this play was created and staged, and 1983 when it was published.”

Compared to only two plays before 1981, a large number of novels, poems, stories, essays and plays have been written after 1981 that seek to understand the circumstances prevailing in the nineteen eighties by engaging with the gruesome happenings of the Partition. In his play “Te Rome Jalda Reha” (And the Rome Remained Burning), Som Pal (Born 1975) made use of Bhagwan Dhillon’s literary writings, his diary entries and the records of his meetings with Pakistani writers. The temporal span of some such writings is the period from 1947 to 1984. A few plays deal with the period that followed 1984. By way of an example, in Sahib Singh’s play Amar Katha (An Eternal Story), the character who was Noora before 1947 becomes Naurang Singh after 1947. When he has to travel to Punjab in 1984, he becomes Naurangi Lal to save his life. Thus, the Partition violence and the violence that took place in 1984 forged multiple identities of a single character in the play and the play affirms life and hope in the midst of death and destruction. Mohan Bhandari’s (Born 1937) story Paarh (Breach) and Waryam Sandhu’s (Born 1945) Parchhavein (Shadows) have also been written on the similar pattern. Many other Punjabi plays with 1947 serving as a backdrop have been written. Punjabi playwrights seem to be of the opinion that efforts are still being made to inject communal poison in the society and the people must be made aware of such nefarious designs.

*

[…]

Notwithstanding the fact that most Partition plays were written after the dust had settled down, the most important question that we face today is to what extent our playwrights were able to control their religious passions? This question assumes greater importance in the context of what Alok Bhalla has to say in his Introduction to the anthology of Stories About the Partition of India Part I to III edited by him. According to Bhalla some stories have been inspired by communal passions, which are alien to inclusive Punjabi sensibility. In such stories he includes Ahmed Nadim Qasmi’s famous story Parmeshwar Singh also. The story is about a Muslim child Akhtar who gets separated from a group of Muslims that was migrating to Pakistan. Parmeshwar Singh takes him home. He feels that Akhtar is like his own son Kartara who had got separated from the family. Parmeshwar Singh loves him deeply, provides ample security but the rest of his family and society do not accept him as a Muslim. Akhtar loves Parmeshwar but hates others. Finally, one morning, while directing him towards his village from the border, Parmeshwar tells him to move towards the direction of the Azan. According to Bhalla, this story is “cynically manipulative” because the Sikh family on this side could not convert the boy into a Sikh, and going back to his Muslim home signifies a victory of his Islamic faith. Bhalla’s interpretation of Parmeshwar Singh’s character ignores the uniqueness of Parmeshwar Singh’s humanity and the piety of his emotions too. If symbolism has to be accorded such priority then even this fact should also be kept in mind that the story does not come to an end with Akhtar’s departure; hence, Akhtar moving in the direction of Azan is not the final image in the story. Later on a Pakistani soldier fires at Parmeshwar. In the last sentence of the story, another powerful image emerges: “And Akhtar was running with his hair flowing in the wind.” The image of Akhtar coming back is much more powerful and lasting than the image of his departure. We cannot interpret Akhtar running towards Parmeshwar as his return to the fold of Sikh religion. In fact, Akhtar is running towards the person he deeply loves. Neither was he going to Pakistan for Azan, and nor does he return because of his hair. The sound of Azan and his hair are minor realities; for Akhtar, his mother and Parmeshwar Singh are much bigger realities. This is a victory of humanity and human relationships over bestiality and communalism, Hindustan and Pakistan, and over that narrow and fake religiosity which separates human beings from one another.

No doubt, some glimpses of communalism are also discernible in the Punjabi Partition drama. Religion is an inextricable part of our culture and cutting oneself off completely from it and stepping out of our cherished beliefs is not an easy task. The larger issue is that of our responsibility as writers. This is equally significant that we cannot cut ourselves off from our shared culture also. Intizar Hussain, the author of Basti, a very important Partition novel in Urdu, believes that we may have divided our country, but we should eschew dividing our common history. In a denial of our combined history, an ordinary Pakistani citizen has started considering even a great poet like Ghalib and a great architectural marvel like the Taj Mahal as alien entities. Intizar Hussain is right in suggesting that such efforts can make people schizophrenic.

Punjabi Partition drama, in general, attaches great importance to our common cultural heritage. But the tone and tenor of some plays written by Roshan Lal Ahuja (1904-90) are contrary to this. In his play Jauhar, Hindu and Sikh widows jump into a well and commit suicide. There is no doubt that Ahuja has portrayed the actual incidents in Rawalpindi which unfolded in a well-planned manner against the Sikhs and Hindus. But towards the end of the play, the dialogue that takes place between a character called Khan Sahib and some Sikh women reveals the repressed hatred of the playwright for the other community. In Ahuja’s play, women fall into simple binaries of Muslim women and Hindu/Sikh women. On the other hand, Agyey’s story Revenge conveys a morally sound message that the humiliation of one woman is the humiliation of the entire womankind. Contrariwise, about his play Khakastan Zindabad , Ahuja himself makes a one-sided comment: “These women’s offering themselves to the pyre is a great sacrifice, which only an Indian woman can make; no woman from any other country can do that. A Muslim woman has never done it to honour her fidelity to her husband.” This is common knowledge that it is not only Hindu and Sikh women who faced this crisis; many Muslim women also committed suicide to save their honour. Fajjan tells in The Bridge of Siraat how many Muslim women saved their honour by jumping into the river. Afzal Tauseef, who wrote the moving story Tahli Mere Bachray (My Kids, O Sheesham Tree) is a witness to how in Indian Punjab village Simbli four young daughters of her father’s elder brother had saved their honour by jumping into a well.

But communalism is not a part of the Punjabi temperament as such.

Intizar Hussain wants to understand his Islamic faith in relation to India because he feels that without this, his Islam is incomplete. Punjabi drama is not Sikh, Hindu or Muslim drama, it is a drama which defends human values.

Here, we can mention the play Chhavian di Rutt (Savage Harvest), which is not included in this anthology. It is based on Mohinder Singh Sarna’s (1923-2001) story by the same title which is perhaps one of the best examples of loftiness of Punjabi creative spirit. The story is set in a border village in Pakistan where all the Hindu and Sikh villagers have been murdered by the Muslims and plans are afoot to kill an old Muslim lady. While adapting this story into a play, the author Master Tarlochan (Born 1957) has changed the spatial matrix of the story from being a Pakistani village to an Indian village. Those who die are Muslims and their killers are Hindus and Sikhs. This prudent strategy has been adopted to make people from the Indian Punjab realize their guilt.

Punjabi sensibility needs to be understood in a different way. Ghulam Abbas’s (1909-1982) Avtar (Incarnation) is a story of Sambal, a town neighbouring Moradabad. Many years after the massacres of Partition, this fact comes to light that the homeless Muslims used to drink water from an old well in the vicinity of a dilapidated and nearly forgotten temple. Communal riots begin once again on the issue of the Muslims polluting the water of the well. Contrary to this, when Pala Singh in Lochan Bakhshi’s (1923-2001) story Dhoorh Tere Charna Di (Dust of Your Feet) revisits his native village in Pakistan twelve years after the Partition, he comes to know that the villagers had stopped drinking the water of the well only because they suspected that the Sikhs might have poisoned the water before migrating from the village. This was the only well with potable water in that entire sandy belt and people walked miles to get water from another well. In order to allay their fears and to prove that the water of the well is pure as nectar, Pala Singh drinks it in front of all the villagers. The residents of Sambal could not get over their rancour which was engendered by the tragic massacres of the Partition and for long years they carried this burden on their minds. But the Punjabis threw away their anger and hatred in 1947 only; they did hold on to their doubts but the moment their doubts were cleared, they came closer to each other than they were before.

[…]

Shahid Nadeem’s (b. 1947) Dukh Darya (River of Sorrow) is an important text in which the large-hearted author has been audacious enough to very appropriately employ the legends associated with Ram Tirath, and the positive aspects of the cultural traditions of the Nath Yogis. Shahid, in experiencing the pain of Partition transcends the geographical and religious barriers of both the countries. River of Sorrow is a quintessential Punjabi play which talks of the oppression as well as magnanimity of the Punjabis; it is history as well as myth; and, it represents real politics as well as cultural realities such as respect and disdain also for women. The waters of our rivers drown us in sorrows, and the same waters also wash away the sorrows.

A reference to Gurpreet Ratol’s play The Village of staged in 2017 won’t be misplaced here. This play is based on Sarbjinder Singh’s book Deejai Budh Bibeka (Grant Me a Discerning Intellect). It is the story of S. P. Singh Oberoi’s native village Dhrabi (now in Pakistan) where the Muslim villagers, in the midst of Partition madness, set a beautiful example of communal harmony which is simply the stuff of dreams. Oberoi happens to be the same person who had paid blood money to save seventeen Indian and Pakistani citizens in the UAE who were awarded capital punishment on a murder charge. For Bachan Singh in No Man’s Land, his first and last dream is his village Toba Tek Singh; in the same way, for the natives of Dhrabi, their village is their top priority. In The The Village of Dhrabi, Sikh characters Mohna and Pritam are prepared to convert to Islam for the sake of their friendship with Chiragh.

In The Bridge of Siraat, Karmo was opposed in principle to a Muslim daughter-in-law because she believes that it would pollute their house, but in practice, she did keep the door ajar. Her son Jassa told her that they would baptize her as a Sikh before marrying her. There are many references to such practices the Sikhs took recourse to in those days to skirt around the issue of ritual purity and impurity. Perhaps it is the inclusiveness of the Sikh ethos that allows for such acceptance to a Muslim woman. Sahib Singh’s play Puro based on Amrita Pritam’s novel Pinjar, is a story of a Hindu family in which the heroine Puro turns out to be a courageous individual with indefatigable spirit. Towards the end of the play, she announces, “I don’t belong to any religion; I’ve nothing to do with any religion … tell your religions to leave me alone.”

*

Feminist [Gender] concerns occupy a place of prominence in Punjabi drama. Beginning with the pioneers like Ishwar Chander Nanda to the well-established contemporary playwrights, most of them have written woman-centric plays. It is women who had been hit the hardest by the Partition. In her famous poem I ask unto Waris Shah when Amrita Pritam calls on the Sufi poet Waris Shah, “A million daughters weep today and look up to you for solace”, she becomes the collective voice of all the tormented women of Punjab. When Harsaran Singh portrays the agony of a helplessness woman in his play Helpless Woman, utter despair takes hold of us and nothing is left but heartache. An abducted woman begets two sons in East Punjab. When she has almost reconciled herself from separation from her sons from her previous marriage and has made a compromise with her new life, a Pakistani police officer who turns out to be her cousin, comes to take her to Pakistan. With her mind split between her love for her sons and family in India where she was had found security and respect, and her love for her sons in Pakistan, she finds herself in a bind. The issue here is not of Pakistan or India, but of her children, two of them are on one side and two on the other side of the border and she cannot be blamed for all this. The entire blame is that of men, but it is women who pay for their sins. In Atamjit’s play Chirhiaan (Sparrows), the law favours sending an abducted Sikh woman from Pakistan to India, but despite her pitiable condition, she is not prepared to go. She has seen how the people in those times treated the women who came back after their abduction. Rajinder Singh Bedi’s Urdu story Lajwanti is a classic which explores not only the silence that attended the Partition trauma but also the psychodynamics of hurt male psyche when the male protagonist Sundar Lal’s wife Lajwanti is abducted and is then repatriated to him; Lajwanti, the eponymous heroine of the story maintains complete silence throughout.

Sita in Sagar Sarhadi’s Messiah, like the protagonist of Manto’s story Open It is a distraught soul and does not recognize her brother till he dies. Similarly, in Season of Healing Wounds, when Fazlu visits India three decades after the Partition, he brings with him all sorts of ointments prepared according to his father Karamdin’s recipes. These ointments could cure all kinds of wounds, but he had no salve for Nafisa’s wounds. In Abducted Woman, the abduction of women is the major issue. When the abducted women settle down in their new families, a process which is extremely painful, their abduction is symbolically re-enacted, this time by the law enforcing agencies which send them to the country of their previous families. And then there are such women also who don Sikh attire but offer Namaz in their minds while sitting in a Gurudwara. Similarly, many women who embrace Islam remain Sikh at heart. And then there are Sikh women in The Lost Village who fight valiantly against the rioters but commit suicide by jumping into a well to avoid being captured by the rioters. Hence, these plays foreground the sufferings of the women.

Pali Bhupinder in his Leeran di Guddi (Doll of Rags) and Khalid Hussain (b. 1945) in his story Soolan da Salan (Dish of Thorns) have built their narratives around the story of Kausar, a woman who was swept to India by the river waters from Pakistan. Khalid was a witness to this real incident because he was the Deputy Commissioner of Poonch in Kashmir. First he wrote the story Dish of Thorns and then the play Dard Vichhora (Pangs of Separation). Whereas Pali’s play is primarily concerned with women’s issues, Khalid Hussain casts his net wider to question the laws of both the countries also. When both the countries consider even that part of Kashmir as their own which is under the control of the other side, then why different laws are applicable to Kashmiri women, especially when this differential becomes a major cause of suffering for women who unwittingly enter the ‘other’ Kashmir.

Shahid Nadim also got this subject matter from Khalid Hussain. But Nadim’s composition is not linear, it is a very intricate inter-text, multi-layered and polyphonous. This is how it operates at multiple levels; it is about the Partition, trauma, suffering and women. The hegemony of feudal and patriarchal cultural mores in both Punjabs is responsible for the plight of women. Kausar was labelled barren by her family in Pakistan. She gives birth to a girl after being raped by an Indian policeman. Thus, her rape evokes conflicting emotions in her; she feels humiliated but this humiliation also proves that she is not barren. She wants to go to Pakistan with her daughter. However, Kausar can go to Pakistan but her daughter cannot since she is born in India. Shahid has also created another story of a Hindu woman that runs parallel to Kausar’s story. He very skilfully interweaves reality and myth by bringing in the legend of the Ram Tirath in Amritsar, Lord Valmiki, Lord Ram and his sons Luv and Kush. As the legend goes, the cities of Lahore and Kasur in Pakistan derive their names from the names of Lord Ram’s sons; Lahore from Luv and Kasur from Kush. In this way, woven into Shahid’s text are the three stories of separation of three women, Kausar, the old Indian woman, and Sita. Just as Intizar Hussain claims that his sources are the tales of Alif Laila and Katha Saritsagar, in the same way, Punjabi psyche is an amalgam of Indian and Islamic traditions; at times it is the Islamic tradition which is prominent as in folk legends and Sufi poetry of Punjab, and at times, the Indian tradition shines bright as in Gurmat poetry. In foregrounding the syncretic Punjabi culture, Shahid Nadeem’s River of Sorrow is a unique text.

Swarajbir’s play The Bridge of Siraat focuses intensely on the helplessness of a woman. Fujjan gets converted into Harnam Kaur after her abduction. But she cannot extricate herself mentally from her parents and religion. She loses her mental balance when her son becomes a Khalistani militant in 1984. In the final dialogues of the play, she emerges as a symbol of Punjab. It is as if both Punjab and women are crossing the narrow bridge on Siraat. In a similar way, in 1947- A Journey Back in Time, there is a very moving scene in which some hooligans catch hold of the chunni of a girl running to save herself from them. They brutally tear her chunni, turning it into rags in no time. Two other young men arrive on the scene with forcibly abducted girls and put on the heads of these shocked girls the chunnis of the colour of their religion. Then a plaintive song penned by the famous Pakistani poet Ahmed Rahi is sung: “My chunni is in tatters/ Brothers, my chunni is in tatters/ All values shattered, all taboos transgressed/ Everyone is blind here/ My chunni is in tatters.” Another destitute woman, very aptly named Punjab Kaur, is from Hansa Singh’s (Born 1949) play Panjo, which in turn is based on a poem written by Mohinder Singh Bhattal (Born 1950). It is double whammy for her; after losing her husband in 1947 she loses her son in 1984. In Satwinder Begowalia’s play Soil and Freedom, we see a woman who prefers to die fighting the marauders rather than be killed by her own father in order to save his honour. But unfortunately, such resisting women are not provided sufficient space in these plays to grow to their fullest potential.

Sahib Singh’s play Puro is a serious attempt at grappling with the problems faced by women during the country’s Partition. The play brings to light some very crucial facts about how patriarchy treats women as a mere commodity and also the resistance put up by women. We learn how men use women as a tool to settle personal scores; the social stigma the family of an abducted woman faces is sought by to be avenged by bringing similar disgrace to the family of the abductor. We learn that a woman has sympathy for another woman even if the other one might be the real sister of her cowardly fiancé Ram Chand. Puro senses that her son too is a male and rather than being happy at being a mother, she is anxious about the possible dangers her son’s machismo can pose to a woman in the future. She exposes those who exploit women in the name of religion. She does not forget her relations easily, even if that person happens to be her timid fiancé. Her courage knows no limits; she can escape from Rashida’s grip but it is the pusillanimous androcentric society that does not accept her. The play asserts that a woman has no ostensible religion.

*

[…]

Most Punjabi Partition plays do not endorse narrow nationalism of any hue, rather they seek to reinforce the roots of the traditional solidarity among different communities. Insular politics holds greater importance for those who remained unaffected by the Partition mayhem. Targeting both the countries in The Lost Village, Saudagar Singh raises a crucial question: “Is it freedom or destruction? Someone should bring Gandhi, Nehru and Jinnah and show them all this! Will they build their Hindustan and Pakistan on piles of dead bodies?” In Kartar Singh Duggal’s Sharnarthi da Coat (Refugee’s Coat), a passenger in a train says, “What celebrations? We Punjabis have been ruined.” Munni Bai, a prostitute who came from Lahore to Delhi in Suraiya Qasim’s story “Where did She Belong” makes an eloquent comment that the Partition did not impact the rich as their nationalism kept rotting in their night long debaucheries as it did in the past. Bishan Singh in Black Blood expresses his anguish in these words: “Noordin’s fields have been left in India and Jaimal’s in Pakistan. Don’t know how the villains have drawn the lines?” Similarly, when Jawali in Duggal’s Sweet Water says, “We’d heard about the kings being dethroned, but had never heard about subjects being displaced,” she actually expresses her deep sorrow rather than commenting on politics or nationalism.

Although in the history of literature in West Punjab, most Hindu and Sikh literary authors do not find any place, but such a thing has not happened in East Punjab. For this very reason, at the time of his departure from the border the Professor in No Man’s Land says, “Though they may have divided the land and the people, but we are never going to divide our syllabi. We’d read Sheikh Farid and we’d read Waris, too. Hashim is also ours, and Mukabal is also ours. Keep writing more … we’ll read them ourselves and also teach in our classes.” This is a telling comment on how education of our composite culture should not be made a victim of divisive politics.

In his novel Kitney Pakistan (How Many Pakistans) the Hindi writer Kamleshwar (1932-2010) thinks of Pakistan in terms of fragmentation of human psyche. To the novel’s hero, Pakistan stands as a symbol of not accepting anyone undivided and whole; it is like a black hole where all sensibilities have died and the joys and pains of others have no meaning. It is a powerful text that presents a bleak and gloomy image only. But the Punjabi drama inspires people to transcend narrow nationalism and politics. The idea of Pakistan has been definitely ridiculed but only by way of satirizing it; on the whole, the reality of Indian and Pakistani nationhood has neither been opposed nor denied. Punjabi drama accepts the reality of Pakistan; it only rejects the viewpoint of religious fundamentalists of all hues and colours. Fundamentalism certainly embitters the relations of the two characters in Blind Shooters but this is not the final message of the play. The final message emerges through the character of Gurmukh Singh who espouses inclusive nationalism which is an ideal to be pursued.

In our country many people have certain misconceptions about Muslims, such as that they are untrustworthy. Most Punjabi plays dispel such specious stereotypical views; The The Village of Dhrabi is an example in hand. A Muslim character in The Lost Village is also espouses this view. For the compos mentis, their nation is universal brotherhood, which transcends all national boundaries. It is very satisfying to add here that the Punjabi Partition drama, in general, falls in the category of “good writing” as Rushdie would define it, for he says in Step Across This Line that “Good writing assumes a frontierless nation. Writers who serve frontiers have become border guards.” Most of Punjabi Partition drama looks toward a frontierless world.

So far as misconceptions are concerned, there are many about the Sikhs also, a glimpse of which we get in K. A. Abbas’s story Death of Sheikh Burhanuddin. The protagonist Sheikh Buharauddin’s hatred for Sikhs is visceral. They appear like beasts to him because of their flowing beards and he dreads them. According to him, Sikhs are stupid as well as unclean and shabby. However, a Sikh neighbour sacrificing his own life to save the life of the Sheikh signals the demise of Sheikh’s misconceptions about Sikhs.

Punjabi drama charts a separate trajectory for this reason also that the Punjabi authors are aware of the fact that for varied reasons, Muslims and Non-Muslims had very close relations with each other in Punjab. There is no denying the fact that in this land of five rivers, the water for the Muslims and Hindus/Sikhs had already been divided owing to ideas of ritual purity and impurity prevalent in the Indian society since ages; the water-carriers filled water in separate sumps earmarked for Hindus/Sikhs and Muslims, and there used to be a third water trough for livestock. But this is also undeniable that on a personal level, the relations between the two communities were very cordial and ran much deeper. Kirpal Singh Kasali’s Barbed Fence is worth mentioning in this regard.

From the nationalistic perspective, the soldiers of the two countries are enemies; but from the cultural perspectives, they are like brothers. Such ambivalence finds its way into most of Punjabi Partition drama.

If our mawkish religiosity and nationalism tend to divide us, then our common culture and language unite us. This is why in literary works, young Sikh and Muslim boys remain steadfast in their friendship with each other; Sikh teachers take their Muslim students to the school on their bicycles; and when Pakistani citizens visit their native villages in India, to them this journey is no less than pilgrimage. Even today, when people from both the Punjabs meet, they embrace each other affectionately and laugh boisterously; and when they part company, then they cry inconsolably. A famous poem penned by Ustad Daman (1911-1984), which has been used by Kewal Dhaliwal in his 1947- A Journey Back in Time, sums up these dilemmas and ambivalences of dual attachments:

We may not voice it, but inwardly

Lost you are, and lost we are.

Buffeted by this freedom,

Ruined you are, and ruined we are.

When those arisen looted with both hands,

You slept over, and so did we.

Redness of our eyes narrates,

You cried your eyes out, and so did we.

But this situation is peculiar to Punjab. It is not necessary that non-Punjabis may also feel the same way. Although Balraj Sahni’s (1913-1973) play Ki Eh Sach Hai Bapu (Is It True Bapu) is not directly about the Partition, yet the dialogue in it between Gandhi, Nehru and Bhagat Singh on the issue of nationalism is quite meaningful. Bapu emphasizes the fact that many misconceptions about Muslims have been spread in the country. He says, “If you look at the people, you’ll find that Hindustan is not a country of Hindus and Muslims; the real nationality is Punjabi, Kashmiri, Gujarati, Tamil and Bengali.” If this is true, then the question that raises its python head in front of us is, why did we Punjabis show such bestiality during the Partition?

*

Pakistani poet Tariq Gujjar (Born 1969) writes:

While giving me birth

Mother earth got split into two.

Taste the bitterness of my words and you’ll know

That the first food I received was waters blended with blood.

With broken instruments

Songs full-scale can’t be sung.

Half of my flute was left on that side

While crossing the river.

Similar nostalgia haunts the characters of No Man’s Land also. An official in the asylum tells the inmates that two countries have come into being now. And then the following dialogue ensues:

Roop Lal: How can they be complete when they have already been divided?

Professor: Now how can you make two trees out of this one?

Employee: By cutting it.

Saleem: Then you’ll end up creating two half trees.

Roop Lal: One will have no roots, and the other, no fruits. How will they be complete …?

There are many troubling issues to which we are yet to find answers: What led to the division of the country? How to come to terms with the trauma of Partition? How to grow out of this trauma, and how to reconfigure our relationships in the present times? But it has not been very long since the Punjabi drama started grappling with these issues and introspecting about them. Politics and history have already concluded that the seeds of the communalism were sown by the colonisers. This has been projected in many plays also. But had it been true, then our past, before the arrival of the English colonisers would have been a golden era of communal amity. The retreating colonials would certainly have wanted the division of the country, but they would not have imagined, or perhaps not even wanted, that we would massacre each other with such ferocity and hatred, and in doing so we would so shamelessly decimate our cultural values also.

Partition drama has gestured towards some other problems facing us. We were willy-nilly encumbered by political and religious hang-ups. Noteworthy in this regard is the dialogue in the play Kahani Wala Dalgir (Dalgir, the Character of Story) based on Afzal Tauseef’s (1936-2014) My Kids, O Sheesham Tree: “Innocent man … looted … ruined … a wounded farmer … a victim to politicos … a victim to religionists.” In the end of Amir Nawaz’s (b. 1977) adaptation of the story Parmeshwar Singh, flowers are sprinkled on the dead body of Parmeshar Singh to the accompaniment of a song: “Hindu-Sikh won somewhere, and somewhere Muslim did/ Defeated lies the human being/ Look, defeated lies the human being.” Here the victory of Hindus or Muslims is a lesser truth; the bigger truth is that gentle humanity was defeated. This play rejects all kinds of parochialism. More than even Qasmi, Amir Nawaz repudiates, very clearly and emphatically, religious and political divisions, and affirms the supremacy of humanity over every other consideration. This way it creates an atmosphere of contrition for what happened in the past.

[…[

Despite our age-old cordiality and brotherhood, why did this tragedy [Partition violence] happen? The entire Pakistani Punjab reveres Guru Nanak as their Pir even today. Many people in Sind, all the Sikhs and many Hindus worship Guru Granth Sahib because the holy Granth contains the hymns of holy men, Sufis and Saints of all religions. Why did we not bother about even Guru Granth Sahib? One significant reason for all the turmoil is to be found in Mohinder Singh Sarna’s story Jathedar Mukand Singh. Combining two other stories with Sarna’s story, Kewal Dhaliwal scripted a new play titled Katha Collage (Collage of Stories), and he has also adapted Sarna’s story into a separate play with the same title, that is, Jathedar Mukand Singh. The story reveals that sentimentality is the hallmark of the Punjabi temperament in general. Integral to such a temperament are qualities like altruism, spirit of sacrifice and selfless love; and also, proneness to humiliating the other, killing and getting killed. What really matters is what nudges the Punjabis in crunch situations. If the nudge comes from political and religious insularity and conservatism, then we behave in a brutal manner; we lose our sense of reason and forget the humanistic aspect of religion. But if the nudge comes from commonly shared culture and language, then unencumbered by any religious or political baggage, we Punjabis are at one with our own selves and with the other as well, and on such occasions, we are unsurpassable in magnanimity and charity. The evidence of all this can be found in various interviews conducted by Urvashi Butalia, Chander Trikha and Sanwal Dhami with the eyewitnesses of those turbulent times. In Pakistan also, many such interviews conducted by Tariq Gujjar, Yasir Dogar and Afzal Sahil are available on the YouTube. Interviews of thousands of affected people can be found on the website http://in.1947partitionarchive.org.

*

[…]

In the present anthology, full-length plays, short plays which create the ambience of full-length plays, one-act plays and some excerpts have been included. Seven out of the sixteen plays in this anthology are adaptations, four of which are based on stories, two on poetic compositions, and one on a prose composition. No Man’s Land is based on Manto’s story Toba Tek Singh, Parmeshwar Singh on Nadeem Qasim’s story by the same title, The Lost Village on Duggal’s “Before Being Reduced to a Plane”, Amar Katha on three stories by Gulzar Singh Sandhu, and Pilgrimage 47 and Munshi Khan are based on forty poems and Joga Singh’s poetic sketch Munshi Khan (and Gurdev Singh Rupana’s story Mirror) respectively. Gurpreet Ratol’s The The Village of Dhrabi is based on Sarbjinder’s text Deejai Budh Bibeka which narrates the story of the efforts made by the people of the village Dhrabi to save the entire village during the Partition riots.

*

[…]

The tragedy of 1947 has taught the Punjabis that there is no deep-seated, ancestral enmity between Hindus/Sikhs and Muslims. In the same way, 1984 has taught us that there is no old animus between Hindus and Sikhs. The roots of the quarrel lie in politics which exploits us time and again.

We have realized that there are problems in all societies and they can be solved, and that the solution cannot be sought by killing the adherents of any religion.

Even if we accept the East Punjab as Hindu/Sikh Punjab and the West Punjab as Muslim Punjab, sundering the two Punjabs from each other is not possible. The inextricable bonds between us cannot be attributed merely to commonality of language and culture, as well as to a shared history. There is no scope for Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs being separate from each other in the Sikh religion. Guru Arjan Dev welded the hymns of saints, Bhagats, and Sufis of all religions in such a way that they are inseparable. Punjabi literature echoes this oneness and unity.

Baba Nanak is certainly the hero of the Punjabis on both sides of the divide. All the people transcend their ideologies and religions in their reverence of Baba Nanak. Roop Lal talks about Dera Baba Nanak being a bridge that unites us. In Tootan Wala Khooh (The Mulberry Well), Gursharan Singh also places his faith in Waris Shah and Baba Nanak’s common heritage. For this very reason, the Kartarpur Corridor is a corridor of hope for us. Dulla Bhatti and Bhagat Singh are also our common heroes. The advent of the 21st Century had raised many hopes of friendly relations but some incidents in the last few years have dealt heavy blows to this hope.

Nevertheless, there is no denying the fact that both the Punjabs must move on leaving behind the agony of Partition, but without forgetting that we ourselves are also responsible for the traumas we have suffered. Had we been the true followers of Baba Nanak and Waris Shah, then all that happened in 1947 would not have happened. The plays included in this anthology are like mirrors that show us what we are like; followers of Baba Nanak and Waris Shah who did go wrong once. We have to make a resolve that we shall not repeat the historic madness that convulsed our land. We have to remain committed to love as Jigar Moradabadi says:

Unka jo farz hai vo ahl-e-siyasat janen

Mera paigham mohabbat hai jahan tak pahunche.

(Let politicians do what their duty is

Mine is the message of love, let it reach the whole word.)

The plays in this anthology will surely take this message everywhere.

********

Notes The Beacon wishes to thank Sahitya Akademy for permission to print extracts from the Introduction to the volume published by the institution.

Atamjit (b. 1950) is an acclaimed Indian playwright and theatre activist working primarily in Punjabi language.

Atamjit in The Beacon

Leave a Reply