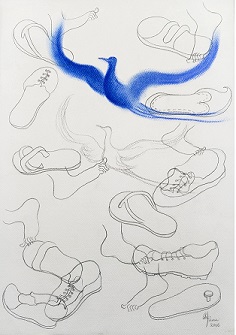

Image courtesy Arpana Caur

Kunwar Narain

{Translated from Hindi Alok Bhalla}

Introduction

Dharma of release, where calm prevails,

And the Dharma of kings, where force prevails—

How far apart are they!

Asvaghosa, Life of the Buddha, translated by Patrick

Olivelli (New York: New York University Press, 2009), p.

263

Kunwar Narain’s Kumarajiva, a long narrative poem in Hindi, was published in 2015. The last work to be published in the author’s lifetime, Kumarajiva is an imaginative meditation on the life of a celebrated Chinese scholar, teacher and translator of Buddhist texts. Kumarajiva was born in 344 CE in Kucha, a famous centre of Buddhist scholarship and art located on the Silk Road as it passed through the Tarim Basin on the edge of the Taklamakan Desert.

Kunwar Narain wrote passionately, and sometimes despairingly, against the absurd and irresponsible acts of political, social and religious violence that have slowly become part our national consciousness over the last two decades. In many of his poems and prose texts, he noted how advocates of peace and tolerance like Gandhi were being cynically pushed to the margins by religious bigotry and majoritarian intolerance. Kumarajiva was his attempt to imagine a society where a people, instead of being proud of their exclusive identities, could learn to pay ‘mindful attention’ to all sentient beings who are as fragile and troubled as they are; to replace aggressive suspicion with nonviolence.

One must emphasise that Kumarajiva is a poem and not a disquisition on Buddhist philosophy or doctrine. It is, instead, a lyric celebration of what Buddhist literature calls sahajata, a life of innate simplicity, infinite patience and enduring compassion. Kumarajiva is not a saint but a teacher who lived during a specific historical time amidst cruel warlords yet never ceased to observe the world with selfless detachment and listen to its sounds with empathy. For Kunwar Narain, he is an exemplum of hope for our dark times; a man whose life-history affirms a fundamental assertion of Mahayana Buddhism that there is no proper time or place for pursuing dharma. It is, therefore, always possible for each of us to dispel our ignorance, refuse to be distracted by the chatter of religious disputations, and reject the politics of power so as to become sravakas (auditor; sra—to hear and vac—voice) of the Buddha’s words.

![]()

We have very few documented facts about Kumarajiva’s life. His father, Kumarayana, a prince from Kashmir, crossed the Pamir Mountains and settled in Kucha. The king of Kucha appointed him as his priest. He married the king’s younger sister, Jiva (or Jivika), who was a devout Buddhist. She insisted that their son, Kumarajiva, should study in Kashmir under well-known Sarvastivadi Buddhist teachers. When Kumarajiva was nine years old, Jiva entered a Buddhist nunnery.

Kumarajiva was an exceptional student whose scholarly fame spread by the time he was twenty years old. After completing his education, he began to give discourses on Buddhism in Kucha. Under the influence of Nagarjuna’s philosophy, he became an adherent of Mahayana Buddhism, which argued that, since there was no unchanging self and we were, at each moment, responsible for our actions, the ‘Buddha path’ was open to all sentient beings, at all times and in every place, instead of only to the self-motivated practitioners of Buddhist tenets.

In 386 CE, Emperor Fu Jian of the Qin Dynasty invited Kumarajiva to move from Kucha to his court in Chang’an on the eastern end of the Silk Road. He sent an army under General Lü Guang to escort him to Chang’an. Instead, Lü Guang conquered Kucha and established himself as its warlord. He imprisoned Kumarajiva for fourteen years, coerced him to marry the king’s daughter and give up his monastic wows of celibacy.

Later, after Fu Jian was overthrown as the emperor of Chang’an, its new ruler, Yao Xing, conquered Kucha and liberated Kumarajiva in 401 CE. Fu Jian appointed Kumarajiva as the National Preceptor (guoshi) of his kingdom. It was under the patronage of Yao Xing that Kumarajiva, with the help of numerous collaborators, began his greatest work of translating Buddhist texts from Sanskrit into Chinese and Tocharian. By the time of his death in 413 CE, Kumarajiva had translated around thirty-five Sutras and two hundred and ninety-four scrolls. His translations are still praised and consulted for their accuracy and the mellifluousness of their verses.

**

Kunwar Narain

(Translated from Hindi Alok Bhalla)

Prologue: Tathagata and I

Tathagata and I have set out

on an immensely long journey

over centuries

we shall travel together

across many ages.1

Who knows

how many settlements

and desolate ruins

our path shall pass through.

We will not stop anywhere

but keep wandering

like the flowing breeze

leaving behind the elegant resonance

of a few words—a few thoughts—

footsteps of wandering sages

resounding at the threshold of every home…

Just as trees and plants

soak light and air

and send the life-giving sap

down to the soil

in the same way

the living-breath of sacred ideas

shall reach down

from the flowers to the roots.

Dispelling the darkness of evil

the fragrance of

all that is good

shall always spread everywhere…

and the colours of joy

shall sparkle…

We shall be seen wandering together

through eternal time

sometimes like the stars

sometimes like the sun.

We can always live like Kumarajiva

just as he had lived like Tathagata

because a Buddha or a Kumarajiva

never dies.

A life of ideas can be lived anywhere

at any time

by imagining it in the past

or making it part of our days

just as Kumarajiva had found

the living message of the Buddha

in his own life and times

and just as a man relives

his ancestral memories

and his scared traditions

by resurrecting them

in the present

and giving them a new life.

The ideas of every devoted

seeker-thinker-artist emerge from

the beliefs of his age

and also reshape them.

A creative life that is aware

of contemporary times

and is harmonious with the eternal

the essence of whose thoughts and acts

dwells in his being

is a perennial presence amongst us

and reappears time after time.

I, Kumarajiva—am a vehicle of Buddha’s teachings—

I am not only a translator of his discourses

they are the medium

for my own teachings.

Interwoven with Tathagatha’s sermons

are my own devotional practices.

Along with Tathagata

my creative writings—

reflecting my own times—

shall be remembered

even after my death

just as centuries later

Tathagatha’s sermons

delivered for his own time

are alive for me

even today!

Every single moment

I live through time and times

Unlike matter

Time cannot be divided

it can neither be broken nor joined like matter.

We split Time into small fragments

only to classify our perceptions—

our understanding.

I can bring to life in the present

any moment in the past

and let other times remain unnoticed

unmarked by consciousness.

Only consciousness can revive dead past.

I alone make my past,

my ancient or medieval days,

my present or future—

my own time and place.

These moments come to us

along the path of our dreams—our thoughts …

The present time

in which I live

has returned after thousands of years

it shall be remembered for centuries after me

sometimes as pre-history

sometimes as ancient…sometimes as medieval history.

With courtesy and humility

I invite Tathagata

from his days

into my time.

Like a book

I open his yuga

in my own yuga.

There is so much

that lies hidden under those text

invisible in the wrinkles of time.

When I read a ‘contemporary’ text

it begins to unravel

and a light

completely different

from today’s glitz and glamour

seeps out of the fissures.

Every book is a closed door

when I open and enter it

I immerse myself in

a ‘spring’ of words

whose source

is the language of its age.

I realise that

I am reborn in an ancient past—

in some unknown place …

My mind and heart are in Jetavana—

in the proximity of Shravasthi or Amravati—

or Sarnath, Sanchi and Patliputra—

where in the living presence of Tathagata

I can sit with Buddhist monks

and listen to his teachings.2

Racing her chariot against the Lichhavis

the sound of their wheels competing with each other—

the courtesan, Ambapalika,

proudly exclaims: ‘Today, Tathagata

will be my guest in Amravana.’

‘Courtesan,’ Lichhavis plead,

‘in exchange for a thousand gold coins

let him be our guest today.’

‘Not even for a thousand gold coins!’

she declares

as she pushes her chariot forward.

Quietly, discretely

I return to my own days—to Kucha3—

and the caves of Kizil4—

in time for the festival of Maitreya5

the future Buddha.

***

********

1.The honorific, Tathagatha, for the Buddha has often been translated as ‘Thus Come One’. It is, perhaps, derived from ‘tatha-gatha’ (Thus Gone] and ‘tatha-agatha’ (Thus Come). See, Leon Hurvitz, Scripture of the Lotus Blossom of the Fine Dharma [The Lotus Sutra] (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009). 2.Located near Shravasthi, the monastery or vihara at Jetavana was the place where the Buddha gave a majority of his discourses. The land originally belonged to Prince Jeta, the son of King Pasenadi of Kosala. The Buddha spent nineteen of his forty-five years of preaching at Jetavana. The monastery has the second holiest tree in Buddhism known as Anandabodhi Tree, named after Ananthapindika, the chief male disciple of the Buddha. 3.Kucha, on the Silk Road along the northern edge of the Taklamakan Desert in Xinjiang, was a major Buddhist centre in ancient China. Kumarajiva was the son of a Kuchean princess and an Indian father. 4.Kizil ancient Buddhist rock-cut caves in Xinjiang, China, near Kucha. They flourished between the 5th and the 8th centuries A. D. 5.Maitreya is regarded as the future Buddha in Buddhist eschatology.

Alok Bhalla is a literary critic, poet and editor based in New Delhi.

Alok Bhalla in The Beacon Kunwar Narain in The Beacon

Leave a Reply