Tarun K. Saint with Vandana Singh

Prelude

This session features Vandana Singh, who is well-known to writers and readers from South Asia and abroad. She is a physicist and writer of speculative fiction brought up in Delhi, and now based in the USA.

**

Tarun K. Saint–Welcome to this session of South Asian SF Dialogues, and welcome back (virtually speaking) to Delhi! You spent formative years in Delhi at a time when environmental activism was coming to the fore, as exemplified in the work of Kalpavriksh. What impact did such groups/movements have on your thinking and writing at an early stage?

Vandana Singh–Thank you! It is an honour to be part of this Dialogue series! The impact of those early experiences has been lifelong. I keep discovering new insights based on my growing understanding of those experiences, one of the most important being a Kalpavriksh trip to Tehri-Garhwal in 1980. All those years ago! A key learning experience for me was that environmental concerns and social justice are inextricably linked; thanks to the Kalpavriksh experience I have never fallen for the elitist model of conservation, which displaces people ostensibly to preserve a distinct and separate Nature. I learned also that so-called ordinary people, the most marginalized, have intelligence, creativity and agency, and that our unequal, pyramidal societies discount and ignore this massive human potential. Another revelation was the leadership of women, that feminism is not exclusively Western, there are many feminisms and the upper class/caste educated do not have a monopoly on these. This early experience took years to ferment and articulate, but I have kept up my connections with environmental justice concerns in India, where I hope to spend increasing amounts of time. These concerns inform my current academic work on a transdisciplinary, justice-centred conceptualization of climate change, and, of course, my fiction.

TKS: Which SF writers were key influences as you began writing and publishing SF? Were writers like Ursula Le Guin as important to you as, say Premendra Mitra, as you have acknowledged elsewhere? How did this hybrid set of influences shape your sensibility?

VS: I began publishing short stories around 2003. I am indebted to multiple influences throughout my life, including writers outside SF. There were lurid little stories in Hindi, thick with fairies and monsters and space voyages, which I read in my pre-teen years. I read trashy science fiction in English as well, graduating from these to Clarke and Bradbury by the time I was twelve. There were also the stories of Premchand, who was a social realist, and yet he’s been a source of lifelong inspiration. I devoured all these in my pre-teen and early teen years, but became disenchanted with science fiction for a while, until I landed on American shores as a graduate student and experienced what it meant to be an alien. Then I began to read science fiction again. In my early thirties my brother urged me to read Ursula Le Guin. What Le Guin did for me was to make me – an aspiring SF writer from another world – feel welcome in SF. I realized that I could make science fiction my country as well, despite being neither white, nor male, nor rich. Later I met Anil Menon at a science fiction convention, at that time the only other South Asian in America writing science fiction as far as I knew. A few years later I discovered Premendra Mitra, and the stories of Satyajit Ray, and then Manjula Padmanabhan and Priya Sarukkai Chhabria, and the classic work of Naiyer Masud. The great thing about influence is that it can become a complex network of give and take – after a critical point, the growing numbers of writers form a kind of dynamic ecosystem of thoughts, ideas and creativity. Now I have lost count of the number of writers – Anglophone and otherwise – from the subcontinent who are doing fantastic creative work, enriching the field, and influencing each other. I count myself fortunate to be potentially influenced by (and perhaps also influence) writers as variedly creative as Indrapramit Das, Mimi Mondal, Gautam Bhatia, Usman Malik, Sami Ahmed Khan and so many others. And then of course we are living in a time when, through the hard work of translators, we can read SF from writers of multiple Indian languages and also languages around the world. Thanks to efforts like those of the Italian SF writer and editor Francesco Verso, and the Israeli writer Lavie Tidhar, we have conferences and anthologies of world science fiction from writers across the planet.

TKS: SF writing in India tended to be seen in a didactic light, as a way of promoting science education. Your work often bridges the gap between YA/children’s literature and serious, ‘literary’ SF. How did you negotiate this legacy of an earlier phase of SF writing at the outset? Is this a false binary?

VS: SF as a means of promoting science education and a scientific temper is such a narrow and impoverished application of the genre! We know that science has been used to promote and justify colonialism and racism, so sometimes the use of SF in this way can also be dangerous. We can see that in early American SF, the so-called ‘golden age’ of white male heroes on colonialist rampages through the galaxy. It has also been the case in other countries that SF has been used as a propagandizing tool for culture change. Even at its most harmless, the use of SF as a medium for furthering an agenda – such as educating people about science – goes against the ultimate value of SF as an art form. Much as I love science, am a scientist by training and choice, and have an academic interest in science education, you cannot hope to produce a work of art if its sole purpose is to teach a lesson! Children and young people are quite understandably turned off by such manipulation. For me, the point of art is to free the imagination. The lessons, whatever they may be, emerge (or not) depending on the needs of the story. The most effective stories are usually (but not always) the ones that don’t go directly for the effect they produce – however contradictory that sounds! What science fiction can do – although it mostly doesn’t – is to shake us loose from old ways of being and thinking by immersing the reader in an alternate world, and therefore posing the ultimate revolutionary question: what if things were different than they are now?

There’s also the notion that children’s stories must be simple and have a clear moral. As a child I hated such stories. We underestimate and devalue children by presenting them with such paternalistic fodder. I write children’s fiction with the same seriousness that I apply to fiction for adults. Children can understand complex aspects of reality if given a chance. This is one reason my Younguncle books, for example, don’t talk down to kids by simplifying language or plot or theme.

Going back to the question of science education, if you want stories to have a role to play in informing people about science, then those stories must be as complex as real science and the scientific pursuit of knowledge – with its failures, wrong turns, appropriations, misuses, as well as triumphs and revelations. If one cares about science, as I do, then one cannot turn away from its problematic aspects, in real life or in science fiction. And it must be pointed out that much of science fiction today is really technological fiction. As someone with a background in theoretical physics, I am far more interested in science fiction that engages with science – what is the universe like? What can we discover about it and about ourselves? Are laws of Nature immutable, or do they change with time? Are there other universes?

TKS: In your speculative fiction manifesto in the collection of stories The Woman who Thought she was a Planet (2009) the ‘What if?’ question underlying speculative fiction is emphasized as having a potentially revolutionary dimension. Could you elaborate on this in today’s context, especially with the looming threat of climate change?

VS: The “what if” question becomes revolutionary when we use it to question establishment thinking and norms. We live in highly unequal societies, where the power structures not only dictate our socio-economic reality but also –subtly and otherwise, condition and constrain our thinking. If we can ask the question “what if social arrangements were different?” such as “what if technology arose from human need instead of being imposed on us by neoliberal corporates?” then we can start to dismantle – at least in our heads and on paper – these structures of power and oppression. With regard to climate change (I research transdisciplinary conceptualizations in the academic sphere), there is a really problematic mainstream discourse that presents the climate crisis in isolation from its socio-economic-ecological context, thereby presenting it as a mostly technological issue. In fact, the climate crisis, the biodiversity crisis, the pandemic, social inequality, are all connected to each other, and the underlying common paradigm is the idea of endless consumption, endless growth, feeding the coffers of the few at the expense of the many. This is a denial of, among other things, physical law, and can only end in disaster. Despite this, people are caught in a trap of the imagination; they can’t even conceptualize living in a different kind of society. What spec fic can do in this context, I think, is to shake us loose from this toxic reality trap into alternative possibilities.

TKS: In your critique of Amitav Ghosh’s The Great Derangement you came to the defense of SF/speculative fiction as a way of alerting us to the dangers of environmental degradation and catastrophic habitat loss, as well as modes of ‘paradigm blindness’ resulting from a blinkered view of scientific advancement. In your stories ‘Indra’s Web’ and ‘Reunion’ you explore the complexity of ‘indigenous’ wisdom and the ways modern sciences like botany might extend epistemological horizons in a time of crisis, even unto the language of the forests. What are the challenges you foresee in reconciling seemingly incommensurable worldviews/knowledge systems in the sphere of climate change fiction.

VS: Western science and various Indigenous ways of knowing both give us essential ways to conceptualize the world. They can be seen as complementary, but with an overlap as well. I’ve come across collaborations between scientists and Indigenous peoples, for example in Alaska, in the context of climate change. The great difference between the two is that Western science is still largely based on reductionism and the separation of the observer from the observed, while Indigenous ways of knowing, despite being very diverse, seem to share the aspect of being relational. My sense is that most thoughtful scientists generally tend to recognize the limitations of reductionism – physicists, for example, know that the universe is amenable to Newtonian physics within a certain domain of validity, and do not misapply it outside that. Ecologists and population biologists and endocrinologists understand this as well, although we are all hobbled by the burden of Newtonian ways of thinking even here. But the mechanistic, reductionist, Newtonian way of thinking tends to be misapplied beyond its domain of validity, well beyond science, to economics and sociology, for example, engendering systems that harm humans and the biosphere. These days there is much talk of reconciling Indigenous ways of knowing with Western science, but here also one has to be careful not to reproduce old colonialist power structures. I’m very interested in exploring collaborative and egalitarian knowledge-sharing that has the potential to change science as well. After all, science is not static, and Indigenous cultures have kept changing as well. Science, in this historical moment, doesn’t do complex systems that well, whereas many Indigenous epistemologies seem to be able to look at the world as a priori complex. I find this fascinating and powerful. I think that such a context could form the framework for a practical and just re-making of the world, in the context of climatic and ecological disaster.

As a fiction writer I try to imagine this collaborative and egalitarian confluence of knowledge systems in various ways. In my journey in science I have often wondered at the insistence on objectivity –you, a part of the universe studying the universe, can hardly separate yourself from it! So there’s no true objectivity possible, all objectivity is temporary and contextual – the only thing we can do is to be honest and think about our relationship to what we are studying. And when we think about relationship, we can’t really isolate the thing. I remember reading a paper on a comparison between these two knowledge systems where the authors had an example – an ecologist who studied moose went to a Native community in Canada, I believe it was, to ask them about the local moose population. He was surprised when a Native Elder started to speak at length about beavers in the area. Only later he realized that you couldn’t understand the moose without understanding the beaver.

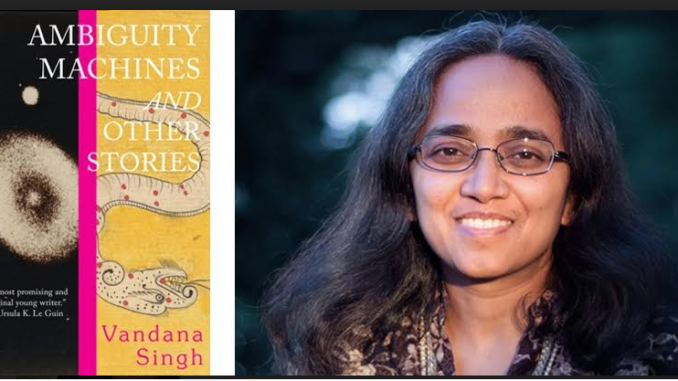

TKS: The anthology Ambiguity Machines and other Stories (2018) has a geographical and cultural range that indicates your extensive travels as a researcher and writer. How difficult is it to get into the skin of characters from marginalized groups in remote areas in existential peril as a result of development and ‘progress’, while retaining the power of story-telling to surprise and astonish the reader, without drifting into the patterns of the tall tale?

VS: Well, because I am very conscious of being an outsider in these communities, I generally write from that perspective. When there are characters from marginalized communities in my stories, they are either seen through the lens of another character who is an outsider, or, they are themselves at a remove from their cultures in some way. Many of my characters are scientists (and women scientists at that) so in some cases they are trying to reconcile their scientific training with their backgrounds. I don’t have the authority to write from an insider perspective, so I avoid that, and leave it to writers who are actual members of those communities. Of course I do extensive research and consultations with people who have access to that insider perspective. I think it is really important to write such characters, otherwise we are in danger of contributing to their erasure. At the same time the insider voices are very important, and I feel an obligation to signal-boost them whenever that is warranted.

With regard to attempting to surprise and astonish the reader without resorting to the tall tale – for one thing, it is important to grant a character their full humanity, whether or not they are from a marginalized group. The point of connection becomes our shared humanity across the abysses of utterly different historical experience, epistemology, and perspective. And many people from marginalized communities live in hybrid worlds formed by the intersection – often violent – of their older epistemologies with modernity. I try to represent those hybrid worlds. As for the tall tale, I actually don’t have objections to it. Sometimes a tall tale can extend the imagination, make it stretchy and pliant, better than spec fic with more verisimilitude.

TKS: In your forthcoming books and stories. Will SF/speculative fiction remain your preferred mode of expression?

VS: Currently, I’m doing a project for the Center for Science and the Imagination as one of four international Climate Imagination Fellows who will be writing stories in the context of the UN Climate Conference, COP 26, coming up this November. I am taking that as a chance to (hopefully) widen some cracks in the edifice of mainstream climate discourse, which is dominated by the same forces that caused the problem in the first place (talk about paradigm blindness!). I have two novels gestating that I don’t have time to write. I wish someone would pay me to take a year off! I also have some half-finished experiments in fiction that represent for me a turn toward a different way of thinking about fiction. Making written fiction ear-friendly, so it can be read aloud, shared and made into something new through community – in other words, a re-turning toward the oral dimension of storytelling.

Alok Bhalla weighs in:

Can SF flourish in a society which is hardly ‘modern’ or technologically developed? Can a society whose scientists are still deeply superstitious really imagine a future (for good or evil) which is rational and concerned with questions about what it means to be human in a society without sanctions from God? Or what it means to have an Indian Self if and when the country does become rationally advanced and scientific. Can one write SF in a society which is not secular? If so, of what kind, given that there can be no speculation about the presence or absence of God? Can there be SF and spirituality?

VS: SF’s origins are indeed in the colonizing cultures of the West. The scholar John Rieder, in his book, Colonialism and the Emergence of Science Fiction connects the birth of SF with imperialism and colonialism. The discovery of new lands through colonialist journeys of exploration is paralleled by the SF trope of journeys to strange planets with alien lifeforms. In that sense, SF is indubitably connected to modernity, and science; in classic Western SF, is presented as an instrument for uplifting the so-called savage – hence ‘white man’s burden.’ The painting American Progress by John Gast rather blatantly shows the colonialists bringing in science, technology and modernity, driving the natives into the darkness ahead. https://picturinghistory.gc.cuny.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/gast-hi-res.png.

But since the 1970s there have been major efforts to take back SF from the conquering white male heroes, starting with women writers in the West, and more recently, African-American and Indigenous writers, and now, with translations becoming available, writers of multiple nationalities are entering the arena. These include writers from formerly colonized nations, some of whom are engaged in talking back to the colonizers through story. Due to colonialism and modernity, most urbanized areas in most countries are hybrid worlds, where modernity and science co-exist, sometimes uncomfortably, with older epistemologies. There is plenty of SF from these countries– from India and Pakistan to Nigeria and Brazil.

As far as superstition is concerned, one must distinguish between the perspective of scientism, which would dismiss any knowledge system other than the reductionist scientific tradition as ‘superstition,’ and those specific elements of any culture which are harmful, violent, exclusionary, and irrational. Currently in the context of climate mitigation even such august international organizations as the UN have recognized, or at least paid lip service to the importance of indigenous ways of knowing, which are seen as complementary to science; ways that have generally resulted in the mutual flourishing of the human and the environment.

As for the existence of God, you can certainly have science fiction about God as an axiom or hypothesis (see for example Ted Chiang’s story ‘Hell is the Absence of God’, or Phillip Pullman’s famous His Dark Materials books), or write SF in the service of some religion or another, although I tend to find these less interesting because positing God stops most of the interesting questions! And I’d rather engage with the questions!

But to return to your earlier point, I think we should be careful what we call superstition – there are a lot of grey areas! That doesn’t mean that there aren’t practices in any society that need to be changed or eliminated, but one would really have to engage carefully with these questions. You may dismiss as superstitious a tribal culture that believes in forest spirits, but they likely have a better record of ecological co-existence than us urbanites, and besides, consider the disproportionate and worshipful importance we give to little pieces of paper we call money! The fact is that when a society or culture gives meaning to something that does not exist except in a metaphorical or abstract sense, it can have real, material repercussions, some of them negative – but that is true in Western societies as well as any other. To me the idea of the invisible hand of the market is just as much rank superstition as, for example, conducting a séance to call the dead; and the former is far more dangerous.

AB, again:

What might be an Indian attitude toward a scientific future? Can it be imagined as being different from SF Futures in the US or Russia? It is interesting that a deeply Christian man like Andrei Tarkovsky does make SF films, and twists and turns Stanislaw Lem and the Strugatsky brothers, who are far removed from religiosity, for his own purposes.

VS: I am not sure there is one, consistent Indian attitude toward a scientific future! There are already many streams and multiple arguments. What do we mean by a scientific future anyway? One can have an endless debate on that question! Does that mean a technological society as in the developed West, which is leading us into ecological catastrophe? Americans live in a highly technological society and SF futures in American science fiction have changed over time, while also being different depending on whom you read. You have the classic golden age science fiction futures with white male heroes saving the day, with a lot of technological positivism, and then you have the more complex, darker portrayals by later and more diverse writers, warning us about nuclear and ecological disasters among other things.

We also have our very own Rokeya Sukhawat Hussain writing Sultana’s Dream, a harmonious and also high tech future where men are socialized to engage in harmless pursuits while women manage the world. A significant proportion of Indian SF in non-English languages that I’ve read tends to reproduce the narrow scientism of the golden age Western SF, in part because there hasn’t been enough cross-pollination between current SF writers from around the world with writers in various Indian languages. I fervently hope that changes. Only through a careful analysis of earlier and current SF in Indian languages as well as Indian SF in English can we come to any conclusion about how the field is progressing, and what the emerging themes might be, and I am certainly not qualified to do that.

However, in fiction I try to play with various possibilities within the wide umbrella of ‘Indian attitudes,’ such as in the story ‘Indra’s Web’, and its sequel, ‘Reunion’, where a new science is presented, arising from the confluence of indigenous and local knowledges and the sciences. That’s my personal, preferred scientific future!

AB/TKS: In the subcontinent, ghost stories about the superstitious past have had a conservative dimension, perhaps due to fear of change. Has contemporary weird fiction and speculative fiction, including your work, become a vehicle for making more sharply critical statements about contemporary dilemmas, whether in the domain of religion, ecology, gender relations or politics, eluding the traps of informal and formal censorship in the process?

VS: I think it is somewhat over-simplistic and misleading to denote the past as ‘superstitious’ and, by implication, the present and future as enlightened (if I am interpreting your question correctly). The pandemic, social media and the rise of authoritarian regimes the world over has shown us that despite an age marked by the highest scientific and technological achievements, we are still capable of living within echo-chambers of lies and falsehoods. I am not an expert on ghost stories and their conservative (or other) dimensions, alas. But certainly, speculative fiction can serve the purpose of social critique, although it has also, perhaps more often, reinforced the status quo. But that is changing, because the field is becoming more diverse.

The power of the ‘what-if’ question in speculative fiction is precisely to question taken-for-granted aspects of the present day. And by setting the story on another planet or among an imagined culture, perhaps spec fic can get around the defensive barriers that people raise to protect their dearest assumptions or illusions about the world. I like to invoke Emily Dickinson in this context, who famously said “Tell all the truth, but tell it slant.” By immersing the reader in an alternate reality, the reader gets a feel for a different world, which may well result in a shift in perspective. The thing is, speculative fiction done well engages us at multiple levels – the literal, conscious mind, and the unconscious, whose language is metaphor and symbol (I’m thinking of an essay by Ursula K. Le Guin here, in her non-fiction collection The Language of the Night). For example, consider the novel by Easterine Kire, When the River Sleeps, about a man on a quest through the rich landscape of Nagaland; it is a literal, physical journey, but simultaneously a story of encounters with multiple non-humans, and a metaphysical quest for self-knowledge.

But speculative fiction has also taken on (with varying degrees of success) our current global issues in a way that (as far as I’ve seen) mainstream fiction simply hasn’t been able to do. That’s partly because spec fic is intimately concerned with the human relationship with the non-human – whether the non-human is an alien or some form of AI, or another species or a planet. And mainstream Anglophone fiction is still obsessively engaged with the human in isolation from everything else. There are a few forays beyond this, such as Richard Powers’ The Overstory, but the richness and potential for this really lies in spec fic (or so I believe), which may well push such narratives from the margins to the mainstream.

***

Link to ‘Mother Ocean’ by Vandana Singh–

https://go.xprize.org/oceanstories/mother-ocean/

*******

Vandana Singh is a professor of physics and a science fiction writer. A particle physicist by training, she currently works on a transdisciplinary understanding of climate science at the intersection of socio-economic and justice issues. Her stories have been published in numerous venues, including several best-of-year anthologies. Her latest collection, Ambiguity Machines and Other Stories was a finalist for the Crossword Book Award and the Philip K. Dick Award. Born and raised in Delhi, she divides her time and energy between Delhi and Boston.

Also read in The Beacon: Dialogues with South Asian SF Writers-1: Bina Shah Dialogues with South Asian SF Writers-2: Anil Menon Dialogues with South Asian SF Writers-3: M.G.Vassanji

Leave a Reply