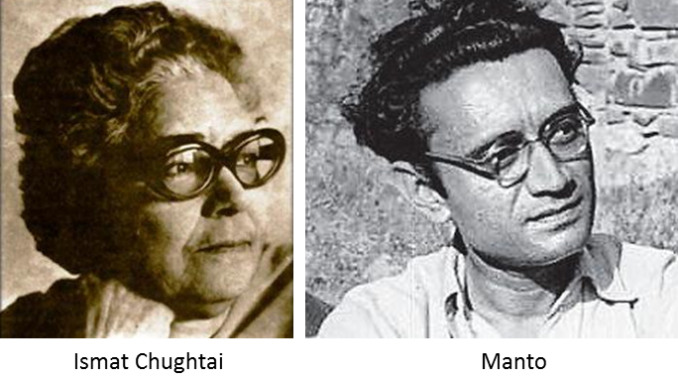

courtesy: urduwallah/wordpress.com

Ismat Chughtai

(Translated from Urdu by M. Asaduddin)

In the name of those married women…

Whose decked-up bodies

Atrophied on loveless,

Deceitful beds

-Faiz Ahmad Faiz

IT WAS about four or half past four in the afternoon when the doorbell rang out loudly. The servant opened the door, then drew back in fear.

“Who’s there?”

“Police!” Whenever a theft took place in the Mohalla, all the servants were interrogated.

“Police?” Shahid got up in a huff.

“Yes sir.” The servant was shaking with fear. “I haven’t done anything. Saab, I swear by God.”

“What’s the matter?” Shahid went up to the door and asked.

“Summons.”

“Summons? But … well, where is it?”

“Sorry, I can’t give it to you.”

“Summons for what? …For whom?”

“For Ismat Chughtai. Please call her.” The servant heaved a sigh of relief.

“But tell me this…”

“Please call her. The summons is from Lahore.”

I had prepared milk for my two month old daughter Seema and was waiting for it to cool down. “Summons from Lahore?” I asked as I shook the feeding bottle in cold water.

“Yes, from Lahore.” Shahid had lost his cool by then.

Holding the bottle in hand I came out barefoot.

“What is the summons about?”

“Read it out,” said the Police Inspector dryly.

As I read the heading—Ismat Chughtai vs The Crown—I broke into laughter. “Good God, what crime have I committed that the Exalted King has brought this lawsuit against me?”

“It’s no joke,” the Inspector said severely. “Read it first and sign it.”

I read through the summons and could barely make out the sense. My story “Lihaaf” had been accused of obscenity. The government had brought a suit against me and I had to appear before the Lahore high court in January. Otherwise the government would penalise me severely.

“Well, I won’t take the summons.”

“You have to.”

“Why?” I began to argue, as usual.

“What’s up?” This was Mohsin Abdullah sprinting up the stairs. He was returning from some unknown destination and his whole body was covered with dust.

“Just see, these people want to inflict this summons on me. Why should I take it?” Mohsin had already passed his law exams and obtained a first class.

“I see. Which story is this?” He asked after reading the summons.

“It’s an ill-fated story which has become a source of torment for me.”

“You’ll have to take the summons.”

“Why?”

“Don’t be stubborn.” Shahid flared up.

“I won’t take it.”

“If you don’t, you’ll be arrested.” Mohsin growled.

“Let them arrest me. I won’t take the summons.”

“You’ll be put in prison.”

“In prison? Good. I’ve a great desire to see a prison house. I have urged Yusuf umpteen times to take me to a prison but he just smiles. Inspector Saheb, please take me to the jail. Have you brought handcuffs?” I asked him endearingly.

The inspector lost his temper. Barely restraining his anger he said, “Don’t joke. Just sign it.”

Shahid and Mohsin railed at me. I was chattering merrily. When my father was a judge in Sambhar the court used to be held in the mardana, the part of the house meant for menfolk. We would watch through the window thieves and robbers being brought in handcuffs and chains. Once a band of fearsome robbers was brought in. They had a beautiful woman among them. A stately figure in coat and breeches, she had the eyes of an eagle, her waist was supple as a leopard’s and she had a luxuriant crop of long black hair on her head. I was greatly impressed by her

Shahid and Mohsin made me thoroughly confused. I wanted the Inspector to hold the feeding bottle so that I could sign but he retreated with shock as though I had held a gun at him. Mohsin quickly snatched away the bottle from me and I signed.

“Come to the police station to sign the surety document. The surety is for rupees five hundred.”

“I don’t have five hundred rupees with me now.”

“Not you. Someone else must stand surety for you.”

“I don’t want to implicate anyone. If I don’t present myself in the court, the money will be lost.” I tried to display my knowledge of law. “Please arrest me.”

The Inspector did not get angry this time. He smiled and looked at Shahid who was sitting on the sofa, holding his head between his hands. Then he said to me gently, “Please come along. It’ll take a couple of minutes.”

“But the surety?” I asked, pacified. I was ashamed of my stupid behaviour.

“I’ll stand surety for you,” said Mohsin

“But my child is hungry. Her ayah is young and inexperienced.”

“Feed the child,” said the Inspector.

“Then please come in,” Mohsin invited the policemen. The Inspector turned out to be one of Shahid’s fans and flattered him so much that he forgot his irritation and began to talk pleasantly.

Mohsin, Shahid and I went to the Mahim police station. Having completed the formalities, I asked, “Where are the prisoners?”

“Want to see them?”

“Sure.”

There were ten or twelve men lying in a huddle behind the railings. “These are the accused, not prisoners,” said the Inspector.

“What crime have they committed?”

“Brawls, violence, pickpocket-ing, drunken fights…”

“What will be the punishment for them?”

“They will be fined or imprisoned for a few days.” I felt sorry that I could get to see only petty thieves. A couple of murderers or highwaymen would have made the visit more exciting.

“Where would you have put me up?”

“We do not have arrangements to house women prisoners here. They are taken either to Grant Road or Matunga.”

After returning from the police station Shahid and Mohsin reprimanded me severel. In fact, Shahid fought with me the whole night, even threatened to divorce me. I silenced Mohsin by saying that if he made too much fuss I would disappear and he would lose his five hundred rupees. Shahid could not bear the disgrace and humiliation of a public suit. His parents and elder brother would be terribly upset if they heard of it.

When the newspapers published the news, Shahid received a touching letter from my father-in-law which ran thus: “Try to reason with dhullan (daughter-in-law). Tell her to chant the names of Allah and the prophet. A law suit is bad enough. That, too, on obscenity. We are very worried. May God help you.”

MANTO phoned us to say that a suit had been filed against him, too. He had to appear in the same court on the same day. He and Sufiya landed at our place. Manto was looking very contented, as though he had been awarded the Victoria Cross. Though I put up a courageous front I felt quite embarrassed. Manto’s visit brought great relief. Shahid, too, felt rejuvenated. I was quite nervous but Manto encouraged me so much that I forgot all my qualms.

“Come on, it’s the only great story you’ve written. Shahid, be a man and come to Lahore with us. You’ve not seen Lahore in winter. We’ll take you around our city. The winter in Lahore is very severe. Aha! roasted fish with whisky—fire in the fireplace like burning flames in a lover’s heart—the blood-red maltas are like a lover’s kiss.”

“Be quiet, Manto Saheb.” Sufiya was getting nervous.

Then filthy letters began to arrive. They were filled with such inventive and convoluted abuse that had they been uttered before a corpse, it would have got up and run for cover. Not only me but my whole family including Shahid and our two month old child were dragged in the muck.

I am scared of mud, muck and lizards. Many people pretend to be courageous, but they are scared of dead mice. I got scared of my mail as though the envelopes contained snakes, scorpions and dragons. I would read the first few words and then burn the letters. However, if they fell in Shahid’s hands he would repeat his threat of divorce.

Besides these letters there were articles published in newspapers and debates in literary or cultural gatherings. Only a hard-hearted person like me could bear with them. I never retaliated nor did I refuse to admit my mistake. I was aware of my fault. Manto was the only person who would get furious at my cowardice. I was against my own self and he supported me. None of my friends or Shahid’s friends attached much importance to it. I am not quite sure, but probably Abbas got the English translation of “Lihaaf” published somewhere. The progressives neither appreciated nor found fault with me. This suited me well.

I was staying with my brother when I wrote “Lihaaf”. I had completed the story at night. In the morning I read it out to my sister-in-law. She did not think it was vulgar though she recognized the characters portrayed in it. Then I read it out to my aunt’s daughter who was fourteen years old. She didn’t understand what the story was about. I sent it to Adab-e-Lateef where it was published immediately. Shahid Ahmad Dehlavi was getting a collection of my short stories published, so he included it in the volume. The story was published in 1942 when Shahid and I were close friends and were thinking of marriage. Shahid didn’t like the story and we had a fight. But the controversies surrounding “Lihaaf” had not reached Bombay yet. Among journals I subscribed only to Saaqi and Adab-e-Lateef. Shahid was not too angry and we got married.

We received the summons in December 1944 to appear before the court in January. Everyone said that we would just be fined, not imprisoned. So we were quite excited and began to get warm clothes stitched for our stay in Lahore.

Seema was a small baby. She was frail and whimpered in a shrill voice. We showed her to the child specialist who declared that she was in good health. Nevertheless it was not wise to expose her to the severe cold in Lahore. So I left her with the mother of Sultana Jafri at Aligarh and set out for Lahore. From Delhi Shahid Ahmad Dehlavi and the calligrapher who _copied’ the manuscript joined me. The Crown had made him one of the accused as well. The suit was brought not against Adab-e-Lateef but against the book published by Shahid Ahmad Dehlavi.

Sultana had come to the station to pick us up. She worked in the Lahore radio station and was staying at Luqman Saheb’s place. It was a gorgeous mansion. Luqman Saheb’s wife had gone to visit her parents along with their children. Thus the entire place was at our disposal.

Manto had also reached Lahore and soon we were flooded with invitations. Most of the callers were Manto’s friends but many also wanted to have a look at a strange creature like me. We appeared before the court one day. Nothing happened. The judge only asked me my name and wanted to know if I had written the story. I admitted to the crime. That was all!

We were greatly disappointed. Our lawyer kept on talking all the time. We could not make much of it as we were whispering among ourselves. Then the date for the next hearing was announced and we were free to freak out. Manto, Shahid and I roamed around in a tonga, shopping. We bought Kashmiri shawls and shoes. When we were buying shoes the sight of Manto’s delicate feet filled me with envy. I almost broke into tears looking at my rough and graceless feet.

“I hate my feet,” said Manto.

“Why? They’re so graceful.”

“They’re absolutely womanly.”

“So? I suppose you’ve an abiding interest in women.”

“You always argue from the wrong angle. I love women as a man. This does not mean that I want to be a woman myself.”

“Come on, forget this man-woman controversy. Let’s talk about human beings.”

Also read : ‘Lihaaf’ [The Quilt]. Short Fiction by Ismat Chugtai

The second hearing was scheduled for November, 1946. The weather was very pleasant. Shahid was preoccupied with his film. Seema was now a healthy child and her ayah, too, was quite competent. So I left her in Bombay and flew to Delhi. Shahid Ahmad Dehlavi and the calligrapher joined me from there and we went by train. I used to feel sorry for the calligrapher. He was dragged in for no fault of his own. He was a harmless and quiet sort of fellow with down-cast eyes and a permanent frown on his face. I used to feel guilty at the very sight of him. Copying the manuscript of my book had invited all these troubles for him. I asked him—”What do you think? Shall we win the case?”

“I can’t say anything. I haven’t read the story.”

“But …you’ve copied it.”

“I see each word separately and don’t ponder over its meanings.”

“Strange! And don’t you read them after they are printed?”

“I do, to see if there are mistakes.”

“Each word separately?”

“Yes,” He looked down in embarrassment. A few moments later he said, “I hope you don’t mind if I say something?”

“Not at all.”

“Your writings contain many orthographic mistakes.”

“I know. I always confuse siin, swaad, and the, zwai, zwaad, zey and zaal. The same happens with the aspirates.”

“Didn’t you practise spelling on boards?”

“I did and always got punished for these mistakes.”

“Fact is, as I concentrate on words and not on their meanings, you get so impatient to put across your point of view that you can’t pay attention to the alphabet.”

I prayed to God for the prosperity of calligraphers. They would rectify my mistakes and I’d be spared embarrassment.

I WENT to stay at M. Aslam’s house along with Shahid Saheb. Hardly had we exchanged greetings when he began to bow his top about the alleged obscenity in my writings. I was also like a woman possessed. Shahid Saheb tried to restrain me, but in vain. “And you’ve used such vulgar words in your Gunaah ki Ratein! You’ve even described the details of the sex act merely for the sake of titillation.”

“My case is different. I’m a man.”

“Am I to blame for that?”

“What do you mean?” His face was flushed with anger.

“What I mean is—God has made you a man, I had no hand in it and He has made me a woman, you had no hand in it. You have the freedom to write whatever you want, you don’t need my permission. Similarly I don’t feel any need to seek your permission for writing the way I want to.”

“You’re also an educated girl from a decent Muslim family.”

“You’re also educated. And from a decent Muslim family.”

“Do you want to compete with men?”

“Certainly not. I always endeavoured to obtain higher marks than the boys in the class and often succeeded in that.”

I knew that I was being pig-headed, as usual. Aslam Saheb’s face was red hot in anger. I was afraid that he would hit me or his jugular vein would burst. Shahid Saheb was aghast, almost in tears. I assumed a softer tone and said humbly: “Aslam Saheb, actually no one had told me that it was a sin to write on the topic with which “Lihaaf” is concerned. Nor had I read in any book that such disease aberrations should not be written about. Perhaps my mind is not an artist’s brush like Abdur Rahman Chughtai’s but an ordinary camera that records reality as it is. The pen becomes helpless in my hand because my mind overwhelms it. Nothing can interfere with this traffic between the mind and the pen.”

“Wasn’t religious education imparted to you?”

“Aslam Saheb, I’ve read Behishti Zevar. Such revealing things are written there” I said innocently. Aslam Saheb looked upset. I continued, “When I had read it in childhood I was shocked. Those things seemed vulgar to me. But when I read it again after my B.A. I realised that they were not vulgar but crucial things of life about which every sensible person should be aware. Well, people can brand the books prescribed in the courses of psychology and medicine vulgar if they so want.”

“Tender an apology to the judge,” advised Aslam Saheb.

“Why? Our lawyer says that we’ll win the case.”

“Nonsense! If you and Manto tender your apologies the case may be wound up in five minutes.”

“Many respectable people here have put pressure on the government to bring the suit against us.”

“Nonsense!” Aslam Saheb blurted out but could not look me in the eye.

“Do you mean the King of England or the people in the government have actually read the stories and thought about filing this suit?”

“Aslam Saheb, some writers, critics and people in high positions have drawn the attention of the government to the books as being detrimental to morality and urged it to ban them,” said Shahid Saheb in a subdued tone.

“If morally detrimental writings are not to be banned, should we offer homage to them?”

Aslam Saheb growled and Shahid Saheb cowered in embarrassment.

“Then we deserve punishment,” I said.

“Being pig-headed again!”

“No, Aslam Saheb, I really mean it. If I’ve committed a crime and innocent people have been led astray, why should I escape punishment merely by tendering an apology? If I’ve committed the crime and if it is proved, then only punishment can bring peace to my conscience,” I said sincerely without any trace of irony.

“Don’t be obstinate. Tender the apology.”

“What will be te punishment after all? I’ll be fined?”

“It’ll bring you disgrace.”

“Arre, I’ve suffered enough disgrace. It can’t be worse. This law suit is nothing compared to that.” Then I asked, “How much will they fine me?”

“Two or three hundred, I suppose,” said Shahid Saheb.

“That’s all?”

“Maybe five hundred,” threatened Aslam Saheb.

“That’s ALL?”

“Have you come into piles of money?” Aslam Saheb was incensed.

“With your blessings. Even if I don’t have money, won’t you pay up five hundred rupees to save me from going to jail? You are counted among the aristocrats of Lahore.”

“You’ve a glib tongue.”

“My mother had the same complaint. She used to say, _A glib tongue invites misfortunes’.” Everyone laughed and the tension in the atmosphere melted. However, a few moments later he began to repeat his plea for an apology. I felt like smashing his skull and mine as well.

WE appeared before the court on the day of the hearing. The witnesses who had to prove that Manto’s story, “Bu” and my story, “Lihaaf” were obscene were all present there. My lawyer instructed me not to open my mouth till proper interrogation began. He would answer the queries as he thought fit.

“Bu” was taken up first.

“Is this story obscene?” Manto’s lawyer asked.

“Yes,” answered the witness.

“Can you point out a word in the story which is obscene?”

Witness: The word “chest”.

Lawyer: “My lord, the word chest is not obscene.”

Witness: “No. But here the writer means a woman’s breasts.”

Manto was on his feet instantly and blurted out: “A woman’s chest must be called breasts and not groundnuts.”

The court reverberated with loud guffaws. Manto also began to laugh.

“If the accused shows his frivolity a second time he will be turned out for contempt of court or severely punished.”

Manto’s lawyer whis-pered into his ear and he understood. The debate went on. The witnesses could find no other words except “chest” and it could not be proved obscene.

“If the word _chest’ is obscene, why not knee or elbow?” I asked Manto.

“Nonsense!” Manto growled.

The arguments went on. We went out and sat on the benches. Ahmad Nadim Qasmi had brought a basketful of maltas. He also taught us a fine way of savouring a malta. “Squeeze the maltas to make it soft like one does a mango. Then pierce a hole in it and go on sucking the juice merrily.” Sitting there, we sucked up the whole basket

The court was crowded the next day. Several persons had advised us to tender an apology. They were ready to pay the fine on our behalf. The excitement surrounding the law suits was waning. The witnesses who had turned up to prove “Lihaaf” obscene were thrown into confusion by my lawyer. They were not able to put their finger on any word in the story that would prove their point. After a good deal of reflection one of them said: “This phrase ‘drawing lovers’ is obscene.”

“Which word is obscene, ‘draw’ or ‘lover’?” The lawyer asked.

“Lover,” replied the witness a little hesitantly.

“My lord, the word ‘lover’ has been used by great poets most liberally. It is also used in naats, poems written in praise of the Prophet. God-fearing people have accorded it a very high status.”

“But it’s objectionable for girls to draw lovers to themselves,” said the witness.

“Why?”

“Because because it’s objectionable for good girls to do so.”

“And if the girls are not good, then it is not objectionable?”

“Mmm no.”

“My client must have referred to the girls who were not good. Yes madam, do you mean here that bad girls draw lovers?”

“Yes.”

“Well, this may not be obscene. But it is reprehensible for an educated lady from a decent family to write about them.” the witness thundered.

“Censure it as much as you want. But it does not come within the purview of law.”

The issue lost much of its steam.

“If you agree to apologise, we’ll pay the entire expense incurred by you and” Someone I did not know whispered into my ear.

“Should we apologise, Manto Saheb? We can buy a lot of goodies with the money we’ll get,” I suggested to Manto.

“Nonsense!” exclaimed Manto as his peacock eyes popped out.

“I’m sorry. This madcap Manto doesn’t agree.”

“But you…Why don’t you?”

“No. You don’t know what a quarrelsome fellow he is! He’ll make my life miserable in Bombay. I’d rather undergo the punishment that may be awarded than risk his wrath.” The gentleman was disappointed that we were not penalised. The judge called me into the anteroom attached to the court and said quite informally: “I’ve read most of your stories. They aren’t obscene. Neither is “Lihaaf”. But Manto’s writings are often littered with filth.”

“The world is also littered with filth,” I said in a feeble voice.

“Is it necessary to rake it up, then?”

“If it is raked up, it becomes visible and people feel the need to clean it up.”

The judge broke into laughter.

I was not terribly worried when the suit was brought against me, neither did I feel elated now that I had won it. Rather I felt sad at the thought that it might be a long while before I got a chance to visit Lahore again.

I WAS a spoilt brat and used to get bashed up often for telling the truth. But when the disputes were taken to Abba Mian he would decide in my favour. My elder sister who had become a widow at nineteen was extremely bitter about life. She was greatly impressed with the high society at Aligarh, particularly the Khwaja family. I couldn’t get along with the begums of that family even for a moment. I was a madcap, outspoken and ill-mannered. Purdah had already been imposed on me, but my tongue was a naked sword. No one could restrain it.

The world around me seemed like a delusion. The apparently shy and respectable girls in these families allowed themselves to be grabbed, hugged and kissed in bathrooms and in dark corners by young men who were related to their families. Such girls were considered modest. Which boy would have taken interest in a plain Jane like me? I had studied so much that when there was a debate I would beat to a pulp all the young men who were scared of the sight of books. They considered themselves superior to women merely because they were men!

Then I read Angare on the sly. Rasheed Aapa was the only person who instilled into me a sense of confidence. I accepted her as my mentor. In the hypocritical, vicious atmosphere at Aligarh she was a much maligned lady. She appreciated my outspokenness and I quickly read all the books recommended by her.

Then I started writing. My play Fasaadi was published in Saaqi. After that I wrote several stories. None of them was rejected. Suddenly some people began to object to them but the demand from magazines went on increasing. I didn’t care much for the objections.

But when I wrote “Lihaaf”, there was a veritable explosion. I was torn to shreds in the literary arena. Some people also wielded their pens in my support.

Snce then I have been branded an obscene writer. No one bothered about the things I had written before or after “Lihaaf”. I was put down as a purveyor of sex. It is only in the last couple of years that the younger generation has recognized that I am a realist and not an obscene writer.

I am fortunate that I have been appreciated in my lifetime. Manto was driven mad to the extent that he became a wreck. The Progressives did not come to his rescue. In my case they didn’t write me off nor did they offer me great accolades. Manto became a pauper in Pakistan. My circumstances were quite comfortable—the income from films was appreciable and I didn’t care much for a literary death or life. I continued to remain a follower of the Progressives and endeavoured to bring about the revolution!

I am still labelled as the writer of “Lihaaf”. The story had brought me so much notoriety that I got sick of life. It had become the proverbial stick to beat me with and whatever I wrote afterwards got crushed under its weight.

When I wrote Terhi Lakeer and sent it to Shahid Ahmad Dehlavi, he gave it to Muhammad Hasan Askari to read. After reading it Askari advised me to make my heroine a lesbian like the protagonist in “Lihaaf”. I was furious. I got the novel back even though the calligrapher had started working on it, and handed it over to Nazir Ahmad in Lahore. Lahore was then a part of India.

“Lihaaf” had made my life miserable. Shahid and I had so many fights over the story that life had become a virtual hell.

I went to Aligarh after a long time had passed. The thought of the Begum who was the subject of my story made my hair stand on end. She had already been told that “Lihaaf” was based on her life.

We stood face to face during a dinner. I felt the ground under my feet receding. She looked at me from her big eyes that conveyed excitement and joy. Then she cruised through the crowd, leaped at me and took me in her arms. Drawing me to one side she said, “Do you know, I divorced the Nawab and married a second time? I’ve got a pearl of a son, by God’s grace.”

I felt like throwing myself into someone’s arms and crying my heart out. I couldn’t restrain my tears though, in fact, I was laughing loudly. She invited me to a fabulous dinner. I felt fully rewarded when I saw her flower-like boy. I felt he was mine as well. A part of my mind, a living product of my brain. An offspring of my pen.

And I realised at that moment that flowers can be made to bloom in rocks. The only condition is that one has to water the plant with one’s heart’s blood…

*******

Notes -Excerpted from Ismat Chugtai’s autobiography Kaghazi Hai Pairahan] with kind permission of M. Asaduddin.

Ismat Chugtai (1915-1991) was a fierce writer who really needs no introduction. Fiercely independent, an early votary of feminine agency she was often referred to as the 'Grande Dame of Urdu fiction', championing free speech and women empowerment. Her outspoken nature marked her out as an early feminist with her writings on sexuality, class conflict, and femininity. Chughtai wrote for many publications in Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, and after the heat and dust of the Lahore trial in the early 1940s where she was refused to cave in to pressure to apologise for her story, Lihaaf, she would go on to win acclaim. Lihaaf would become hugely popular; her other creatibe works are Gainda, Intikhab, Terhi Lakeer, Garam Hawa, among a host of others.

M. Asaduddin is Professor of English and Advisor to the Vice-Chancellor, Jamia Milia Islamia, New Delhi. Among other writings he has translated Ismat Chugtai’s autobiography, A Life in Words Memoirs. He has also translated and edited four volumes of the complete stories of Premchand.

Lihaaf is raw and real. A powerhouse of writing that breaks boundaries of truth, simply.

The Midnight Knock at 4 pm leaves one laughing and aching at the same time.

Ismat Chugtai is truly a gift to humanity.

Once I had asked my professor that if he were to be re-born, which period in history would he choose? He replied “The very same period as now. 1960-70 is epochal. I would savour it, interact and learn from it, better”.

And how would Ismat Chugtai respond to being asked the same question?

Perhaps similarly!