Mayank Bhatt

B

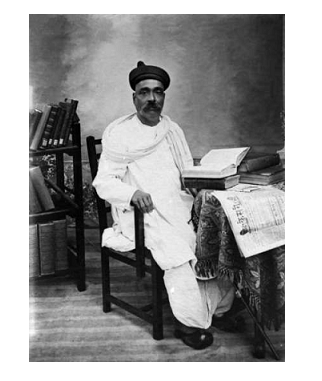

al Gangadhar Tilak (1856-1920) one of the first genuine mass leaders of India’s freedom struggle is deified by nationalist historians and enjoys mass adulation in the centenary year of his death as the only Indian leader who confronted the British Empire at a time when his contemporaries preferred negotiations. However, his long political career reveals he was more than just a unidimensional leader of the masses; he was willing to adapt and change.

India and Indians globally recently celebrated the annual Ganapati festival that Tilak launched as a mass movement in 1893 professedly to unite Indians into a freedom struggle by creating awareness about Swaraj (freedom), Swadesh (nationalism), Bahiskar (boycott of English products) and Rashtriya Shikshan (national education). More than a century later, it embodies Hindutva pride. In an India where democratic institutions have become accommodative and accepting of a majoritarianism doctrine, re-visiting Tilak’s political trajectories might help locate the roots of a festival that is exclusionary and divisive.

Young Tilak’s political career (he was 38 years old when he launched the Ganesh festival) was dominated by religiopolitical mass movements but in his mature years and especially after his release in 1914 from a six-year-long imprisonment in Burma to his death in 1920 he turned a constitutionalist, eager to engage the British and work amicably with other leaders to pitch for ‘Home Rule’

As the father of Indian unrest, as the British described him, Tilak launched successful and effective mass movements in the 1890s – the Sarvajanik Ganeshotsav in 1893, the celebration of Shivaji Jayanti in 1895, and the campaign against British administration’s measures to curb the spread of plague in 1896-1897, which eventually led to the Chapaker Brothers murdering Charles Rand, the Plague Commissioner, and Tilak’s first imprisonment in 1897.

Was Tilak a rabble-rouser who manufactured Hindu anger and manipulated Hindu disgruntlement to gain political ascendency in the last two decades of the 19th century? And, did he compromise on his ideology by turning into a sober political dealmaker, signing the Lucknow Pack in 1916 with Mohammed Ali Jinnah that brought Hindus and Muslims to work together for India’s independence?

Willingness to change

To focus exclusively on the separate phases of Tilak’s political life would lead us to ignore his acumen and adaptability and to erroneous conclusions. Viewed in its entirety, Tilak’s political career from the mid-1880s, when he began to acquire prominence in Poona, up to 1920, shows his adaptability and willingness to change direction to remain relevant.

When he needed to be a chauvinist Hindu nationalist in the last two decades of the 19th century and the first decade of the 20th century he did so with alacrity; when it was expedient to be a constitutionalist to remain relevant in the altered national scenario of the early 20th century (1915-1920), he abandoned chauvinism and appealed to the mainstream by joining hands with Anne Beasant, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, Joseph Baptista, Sir Subramania Iyer and GS Kharpade to form the All India Home Rule League.

Tilak’s contemporary, Gopal Ganesh Agarkar (1856-1895), claimed that Tilak’s conservatism was “the result of calculation, rather than conviction;…he [Tilak] trimmed his sails to catch the winds of popularity.” Agarkar should know; he was the first editor of Kesari, the newspaper Tilak established (along with Mahratta) in 1881 – both were 25 years old at the time. Vishram Bedekar (1906-1998), Marathi author and filmmaker offers penetrating insights in his play Tilak ani Agarkar, 1 into the emotional bond and intellectual conflict between the two leaders; friends who turned into foes.

Historian B. R. Nanda (1917 – 2010) in his biography of Gopal Krishna Gokhale (1866-1915) observes, “Tilak suffered from the malignant hostility of the British while he lived. After his death, he has probably suffered no less at the hands of uncritical admirers, who have tended to present him not as a flesh-and-blood politician, but as a mythical hero.

“The image of Tilak as an uncompromising champion of swaraj, a reckless patriot hurling defiance at the mighty British raj, while the craven moderates lay low, does less justice to the subtlety, stamina and flexibility of a consummate politician who managed to survive the bitter hostility of the government for nearly forty years.” 2

Age of Consent Bill

The genesis of the Ganesh festival lay in the political divide in Poona between the orthodox and the moderates (led by Gokhale). Tilak and his friends, including Agarkar, launched the New English School in 1880 (which later became the Deccan Education Society). It was one of the first native-run schools to provide western-style education in Poona. Gokhale joined the institution later.

Soon, the differences in temperament and beliefs led to a rift, and these became so serious that Tilak had to leave the institution that he had set up. Embittered, he continued his battle with his opponents through his newspapers. Agarkar, increasingly at odds with Tilak’s editorial policy, launched his newspaper – Sudharak in 1888; under Gokhale’s editorship, and later ownership, it became the voice of the moderates.

When Sir Andrew Scoble (1831-1916), then a member of the Imperial Legislative Council of India (the British version of the Indian legislature) moved the Age of Consent Bill in 1891 to raise the marriageable age of consent for girls from 10 to 12 years, the differences between Tilak and moderates, till now confined to newspaper editorials, burst out in the open.

“We would not like that the government should have anything to do with regulating our social customs or ways of living, even supposing that the act of government will be a very beneficial and suitable measure,” Tilak vigorously protested, even as the moderates supported the legislation.

Although a leading British Conservative, Scoble ignored the orthodox opinion in India, and enacted the legislation, noting, “…the balance of argument and authority is in favour of the Bill. Even if it were not so, were I a Hindu, I would prefer to be wrong with Professor Bhandarkar, Mr. Justice Telang and Dewan Bahadur Raghunath Rao than to be right with Pandit Sasdhar Tarkachudamani and Mr. Tilak.” 3

Interestingly, Pandit Tarkachudamani, a protégé of Bankim Chandra Chatterjee (1838-1894), was a leading Hindu revivalist in Bengal, with a large following of his own in Calcutta and had devoted his life to establishing a ‘scientific’ basis of Hindu scriptures.

Tilak too, authored three books on Hindu religion, two of which – Orion – Researches into the Antiquity of Vedas (1893) and The Artic Home of Vedas (1903) – attempted to link science and religion. Later, when he was imprisoned in Burma, he wrote his magnum opus the Śrīmad Bhagavadgitā Rahasya (Secret of the Bhagavadgita) – also known as Bhagavad Gita or Gita Rahasya, in which he reinterpreted the meaning of Gita. Its message was not renunciation he held, but selfless service to humanity.

Tilak’s personal belief heavily influenced his political views. To him, the main reason for India’s cultural and geopolitical unity was the Hindu religion. N.R. Inamdar, a political scientist and historian, explains, “Tilak believed that Hindu philosophy was superior to other philosophies and religions. According to Vedanta philosophy, the reality is ultimately non-dualistic, and man’s final goal is to become one with Paramatma.

“The Bhagwad Gita teaches that man can and must achieve this self-fulfillment through Karmayog – through a life dedicated to the performance of one’s duties in this world of loksamgraha. This karmayoga ethic, Tilak asserted, is superior to materialistic or hedonistic ethics. The latter justified a model of politics centered on the pursuit of self-interest. The former entails a conception of spiritualized politics…”

Inamdar adds, “To Tilak, a feeling of oneness among the people and pride in their country’s heritage were the vital forces of nationalism. He believed that fostering among the people the feeling that they have common interests to be pursued and realised through united political action could develop nationalism. This idealistic and romantic conception of nationalism did inspire and unite the de-spirited and divided people of India.”4

However, Hindu religion is an upper-caste construct that does not have the room for lower castes and especially the Dalits to voice their opinions. That situation has remained unchanged since the religion began to be practiced and was especially so in the late 19th century. Pertinently, the ideals of Hindu religion that Tilak espoused and defended then were being challenged before, during and would continue to be challenged after his time.

The defeat of the orthodox view over the Age of Consent Bill ignited passions across India. “The battle over Age of Consent roused orthodox leaders throughout British India to the consciousness of the actual weakness and potential power of their position. The alliance of foreign rulers with Hindu reformers had proved impervious to the protests of those who valued religious rituals more highly than political independence or social equality. Yet the cry for religion in danger had awakened a responsive chord in millions who otherwise took no note of public affairs.”5

Ganesh festival

Tilak realised it was necessary to build a mass movement to fight the joint might of the British administration and the Indian moderates. The opportunity that he was waiting for came unexpectedly a couple of years later when Hindus and Muslims clashed in Bombay. For four days from 11 August 1893, Hindus and Muslims went on a rampage, leaving 80 people dead, 530 injured and 1,505 arrested. Until then, Hindu-Muslim friction had not erupted into large-scale violence.

But with the rise of new industries, textiles, thousands of Muslim Pathans and Hindu Marathas moved into the city, working, and living in proximity. The ignition in the communally surcharged atmosphere, according to the then Governor of Bombay, was provided by the resurgent propaganda by the cow protection societies (Tilak, incidentally, was a leading functionary of the Gow-Rakshak Mandali in Poona).

The moderates, led by Mahadev Govind Ranade (1842-1901) and Gokhale, urged communal peace, but Tilak and his followers sponsored a mass meeting in Poona on 10 September 1893 to discuss the riots. One week after the meeting, he launched the first modern Ganapati festival.

The year proved to be a watershed. Till then, many Hindus in Poona routinely joined Muslims in their annual celebration of Moharram (when the grandsons of Prophet Muhammad were honoured, by constructing the replicas of their tombs and carrying them in a parade to the river). Tilak declared that Hindus would no longer take part in Moharram. He advocated for a separate festival of Ganapati with similar processions and passions.

With the Ganapati festival, Tilak struck a responsive chord among Hindus. His increasing influence in the affairs of Poona ensured his group gained control of the venerated Poona Sarvajanik Sabha. It was an ironic twist of fate that an association which had spearheaded the social reform movement in the Deccan was now controlled by orthodox leaders. This new phase of emotional revivalism in the Hindu religion, inspired and guided by Tilak, had to reach its logical culmination in political extremism.

The underlying cause of the friction between the orthodox and moderates over the Age of Consent Bill was what should take precedence – political swaraj or social reforms within Hindu society. While Tilak was in favour of social reforms, he wanted political swaraj to take precedence, he preferred social reforms to be guided by Indians rather than foreigners; the moderates differed and argued that social reforms were more urgent than political freedom.

Tilak consolidated his political hold by delinking social reforms and political swaraj in 1895. Before that year, both the National Social Conference (set up by Ranade in 1887) and the Indian National Congress held their annual meetings together at the same venue and both had several common delegates. But in 1895, when he also launched the Shivaji Jayanti, Tilak insisted the two events be delinked. The moderates led by Ranade were relegated to the background. In a fit of pique, they walked out of the Poona Sarvajanik Sabha and formed the Deccan Sabha. The ideological split was complete.

Plague of 1896

The compulsions of marketplace politics and the competition to corner popular support lead both the orthodox and the moderates into another confrontation. Measures adopted by the British administration to prevent the outbreak of bubonic plague were opposed by the orthodox leaders. In 1896 Walter Charles Rand was appointed the Plague Commissioner of Poona. As if that was not controversial enough, the following year the Bombay government enacted the Epidemic Disease Act, 1897, which gave sweeping powers to the administration to search and clean homes of the native population.

![]()

Officials visit house in Bombay searching for people with plague in 1896. . Welcome Images/Wikipedia

Poona was in the throes of political, social, ideological, and economic ferment. There was an ongoing famine across Deccan, which had crippled the economy. When the cleaning operations began in Poona and Bombay, the British administration was expectedly thorough, and ruthless.

Nationalist historians would like us to believe that Rand went about his task with the zealousness of a civil servant, unconcerned with local customs or local sensitivities. But more recent interpretations from a subaltern perspective reveal the hidden role of caste and of Brahmin control over the nationalist discourse. It should be remembered that while the orthodox and the moderates had many differences, the leadership of both the groups mainly comprised Brahmins.

Historian Richard I Cashman gives an insightful analysis of the uneasy relationship between the British administration and the Brahmins in the Bombay Presidency. In his book The Myth of Lokamanya, he observes, “British attitudes toward Brahmans had long been conditioned by a positive fear of this community as the immediate pre-British rulers of the Deccan, and by a distaste for the priestly community, which they blamed for all that they disliked in Indian society.

“Their reliance on this community was born from the needs of administration and order rather than from any positive feelings towards Brahmans. The wily Brahman, inscrutable in his ways, unfathomable in his mind, disloyal in his feelings, clever and intelligent, was a familiar bogey to the British mind throughout the 19th century.”

Cashman illustrates his argument by describing the portrayal of Professor Godbole’s character in E. M. Forster’s Passage to India. He observes, “Professor Godbole, the symbol of Hindu and Brahmanical culture, was presented as cheerfully inept, disorganised, inefficient, and captive of an other-worldly philosophy. When confronted with the question of whether Aziz, a Muslim was guilty of an assault on Miss Quested, an Englishwoman, Godbole launched into a long and circuitous discourse which concluded with the homily that while good and evil were different they were ‘both of them aspects of my Lord.’

“He later presided over a popular Hindu festival which was a ‘muddle,’ a ‘frustration of reason and form.’ Godbole thus epitomised the inscrutable Brahman mind. It is significant that Godbole is a Chipavan name and that Forster’s work was not written until 1924, by which time the Chitpavans had established a reputation for political activism. Forster’s Godbole underlined the British confusion when confronted by Brahmans who acted like Kshatriyas. 6

Atul Krishna Biswas, a retired IAS officer and the former Vice-Chancellor of Dr. B. R. Ambedkar University Muzaffarpur, Bihar, in his essay compares the effect of the 2019-2020 Covid-19 pandemic with the 1896 plague. He implies that Brahminical influences stymied the plague control measures in 1896-1897 and ultimately resulted in Rand’s murder by the Chapekar brothers.

He notes, “Tilak was the pioneer in the anti-Rand campaign and smeared Rand’s reputation in an editorial in Mahratta (25 April 1897), terming Rand’s appointment as Plague Commissioner as ‘an unfortunate choice.’ Biswas quotes Parimala V. Rao’s research (Foundations of Tilak’s Nationalism Discrimination, Education and Hindutva, Orient BlackSwan, 2010) that traces Tilak’s hostility towards and his campaign against Rand to the young ICS officer’s tenure as a Khoti Settlement Officer in Satara district. “In 1894, Rand ordered nationalists to stop playing music in a certain part of Wai in Ganesh procession. He had convicted eleven Brahmins, who had disobeyed the prohibitory orders.”

Stanley Wolpert has more details of Rand’s strict handling of the Wai incident. “As chairman of the newly created Plague Committee, Rand was invested with dictatorial powers. He arrived in Poona preceded by his reputation as a stern disciplinarian for having sentenced eleven “respectable Hindus” to jail for instigating the Wai communal riots of 1894 when he served as the magistrate of Satara District. After passing the sentence, he had obliged these convicted Brahmans to walk under a blistering sun for more than twenty miles from Wai to their Satara prison.

He adds, “But if Rand was regarded with hostility by the orthodox Hindus of Poona before his arrival there, a brief period in the office at his new job in that city sufficed to arouse the hatred of most of its inhabitants against him. Even the Liberal (Sudharak) newspaper, which had so recently advocated the appointment of a “strong officer” moaned,” complaining to the British administration, “the accounts we have been from time to time publishing in our Marathi series will, we have no doubt bear sufficient testimony to the unparalleled distress and the misery caused to the people of this city in consequence of the operations of the Plague Commission as at present directed.” 7

The Poona Vaibhav, Modavritta, Pratod, and Dnyan Prakash, besides Sudharak, joined the cacophony to provoke sentiments against anti-plague measures in Poona.

Tilak and his group started a Hindu Plague Hospital, and Biswas reveals that “Charles Rand’s report specifically noted that the Hospital was open to Brahmin and other upper castes Hindus but out of bounds for lower castes. Rand recorded that ‘of 157 patients’ admitted in the Hospital, “98 were Brahmins and 59 belonged to other castes.” The Brahmin plague patients were 62.42%.

Biswas then quotes a British administration report (The Plague in India, 1896-1897, Vol II) which stated, “…a section of the Brahman community including some of the most influential men of the city,” were disinclined “to support any measures that emanated from an official source, and were more likely than not to work against any operations that might be set on foot by the Government to deal with the emergency.”

To substantiate this claim, the report states that “Malicious rumours were set afloat and disloyal and inflammatory articles appeared in the local vernacular press.” The excitement “culminated in the dual murder of Mr. Rand and Lieutenant Ayerst.”8

The public expression of outrage by orthodox Hindus at the tough measures implemented to control the plague pandemic forced the British administration to adopt softer measures. This prolonged the disease for several years.

According to Tim Wallasey-Wilsey, Senior Visiting Research Fellow, Department of War Studies, King’s College, London, “…the stark truth is that cultural sensitivity had its consequences. The plague was not stamped out – and continued to kill until the mid-1920s. As many as 10 million Indians may have died.” 9

Following Rand’s murder, the British administration arrested Tilak under charges of sedition on 27 July 1897, even though the administration could not link Tilak to the murder. He was tried for disaffection, found guilty and sentenced to 18 months of rigorous imprisonment. Justice Ranade and Parsons denied Tilak bail. Imprisonment turned him into a national hero, and his stature grew manifold, especially outside the Bombay Presidency.

After his return from prison, he continued with his fiery politics and opposed Lord Curzon’s division of Bengal in 1905, formulated the core ideals of passive resistance (later adopted by Mahatma Gandhi), and caused a split in the Congress in 1907 between the so-called extremists and the moderates. The British administration turned the split into an opportunity and arrested Tilak once again in 1908 on charges of sedition and terrorism.

Tilak had editorially supported Prafulla Chaki and Khudiram Bose, who tried to assassinate Chief Presidency Magistrate Douglas Kingsford of Calcutta, but erroneously killed two innocent Englishwomen. Chaki committed suicide when arrested, and Bose was hanged. Mohammed Ali Jinnah defended Tilak in the trial, but the British administration was bent on sending him to prison for a prolonged period and he was transported to Mandalay in Burma.

By the time Tilak was released, the world had changed. Europe was engulfed in a crisis that would lead to a World War, the partition of Bengal was rescinded, Tilak’s opponents – Gokhale and Pherozeshah Mehta passed away in 1915, and Mahatma Gandhi returned to India from South Africa. He was the last of his generation of leaders, and he realised the need to change his methods if he had to remain relevant in the freedom movement.

Cashman, while analysing Tilak’s transformation from a mass movement leader to a constitutionalist, explains, “Released from jail in 1914, Tilak virtually abandoned the tactic of mass movements outside the Congress in favour of more constitutional forms of agitation. Having enunciated the goal of swaraj and having built up a sizeable following, Tilak chose to work within the framework of the Congress and of the legislatures and later to appeal to the British Labour Party.

“Although some of Tilak’s followers regarded the new strategy as a manifestation of caution and compromise, it was born of confidence rather than weakness…in 1915, Tilak was the pre-eminent leader of western India and one of the most powerful figures in the Congress. His new program was designed to harness the hitherto undirected flow of protest into more constructive channels of political pressure.”10

Tilak’s transformation had come full circle – from a leader who directed Poona Hindus not to take part in the Moharram festival, he now represented the Congress in signing the Lucknow Pact in 1916 with Jinnah who represented the Muslim League. The Congress agreed to separate electorates for Muslims in provincial council elections.

When Tilak’s political career is assessed in its entirety, it becomes obvious that he was a shrewd politician who dexterously changed his position as the situation demanded. He pragmatically sacrificed his orthodox moorings, abandoned his propensity to launch incendiary mass movements, and turned himself into a moderate to confabulate with leaders not aligned to his thinking and methods. Adaptability was the hallmark of Tilak’s politics.

******

Author Notes Note: Parts of this article were posted in a different context on www.generallyaboutbooks.com

[1] Tilak ani Agarkar, a play by Vishram Bedekar (1906-1998), author, playwright and filmmaker. Originally published in 1997 [2] Gokhale: The Indian Moderates and the British Raj, B. R. Nanda, Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 1977 [3] Ranade and the Roots of Indian Nationalism, Richard P. Tucker, University of Chicago Press, 1972 [4] Tilak in Political Thought by N. R. Inamdar in Modern India Edited by Thomas Pantham and Kenneth L Deutsch, Sage Publications, 1986 [5] Tilak and Gokhale: Revolution and Reforms in the Making of Modern India, Stanley A. Wolpert, Oxford University Press, 1989 [6]The Myth of the Lokamanya: Tilak and Mass Politics in Maharashtra, Richard I Cashman, University of California Berkeley, 1975 [7] Tilak and Gokhale: Revolution and Reforms in the Making of Modern India, Stanley A. Wolpert, Oxford University Press, 1989 [8] A. K. Biswas’s quotes from Mainstream Weekly May 2020 https://www.mainstreamweekly.net/article9413.html [9] Policy dilemmas from the Bombay plague of 1896 https://www.gatewayhouse.in/bombay-plague-1896/ [10] The Myth of the Lokamanya: Tilak and Mass Politics in Maharashtra, Richard I Cashman, University of California Berkeley 1975

Mayank Bhatt is a Toronto-based author. His debut novel, Belief was published in 2016. View Bhatt's blog: www.generallyaboutbooks.com here.

More by Mayank Bhatt in The Beacon

NEW FICTION: Arthur in the rains

MARRIED TO A BELIEVER

NEW FICTION: Remembrance-I

We are here, ‘cos you were there! The Immigrant’s Anthem

Leave a Reply