Darius Cooper

F

ilms about saints should be made according to the ideology they preached and practiced. The technology of cinema has to surrender to the spirituality of their apostleship. Two films that attain a state of grace are the 1936 Indian film Sant Tukaram directed by Vishnupant Govind Damle and Sheikh Fattelal and the 1950 Italian film The Flowers of St. Francis directed by Roberto Rossellini.

Saints don’t live or preach in an autonomous universe. They are born and live in a secular world that is full of all kinds of contradictions. The saint confronts and questions these contradictions. He challenges those that do harm and tries to replace them by creating a new kind of consciousness that not only improves the self but also instructs it to wipe away all its lapses. He struggles to invent a new kind of maturity, not only about man’s relationship to man, but also about man’s relationship to God. If the second enterprise proves too futile to accomplish, at least the first one is given plenty of room to succeed by the consummate efforts made by the saint setting himself up as a prominent example.

In the case of Francis and Tukaram, this is inaugurated at the outset by the determined rejection of everything that is related to the very idea of sainthood itself. Francis does not impose any of his signs of apostleship but rather shares them with his brothers and we see its equal distribution amongst all the brothers wearing the same benign expressions at all times on their faces; maintaining the same tonsured haircut; wrapping the same rough sheepskin sacks around their bodies in all seasons; and carrying the same pilgrim’s staff through every landscape they traverse. In the opening scenes of the film, when Francis fails to find “shelter” for his brothers from the pounding rain, he acknowledges this failure by insisting that he lie flat on the soaked earth and have the brothers “walk” all over him. This is offered as a penance for that brief moment of arrogance he entertained while believing that whatever “orders” he gave as “a leader” would immediately “be obeyed.” He rejects every halo that any brother tries to impose on him and insists that like them he is only a “jester,” a juggler of God who pursues “innocence” and encourages “silliness” because it is through innocence and silliness that he wants to embrace, both, the world with all its inhabitants, and God. If a fruit has to be plucked from the top of a tree, he enthusiastically climbs on the shoulders of his brothers to the highest point. But, when a rich man beats him and kicks him down the stairs, he rolls away, happily offering no resistance. Both gestures are celebrated in the joyful spirit of neutrality. He praises God not only for the fruits that will be eaten but also for the blows he receives when begging for alms and failing.

Tuka is constantly seen discouraging any claims that are made by his devotees on his privileged relationship with his Vithala or God. We see him constantly using his humbleness, often with a childlike innocence, to show that even though he is, by caste, an untouchable or sudra, God makes no special distinction in claiming him as one of his devotees along with the privileged upper caste brahamins of his village, Dehu. He submits willingly to all the false charges brought against him by the corrupt and jealous Brahmin priest Salo Malo. And when God intervenes and miraculously reverses these ordeals and punishes the wrong doers, Tuka merely steps in and forgives the trespassers. He treats the whole painful altercations as just a common misunderstanding that unfortunately happened on misguided human terms.

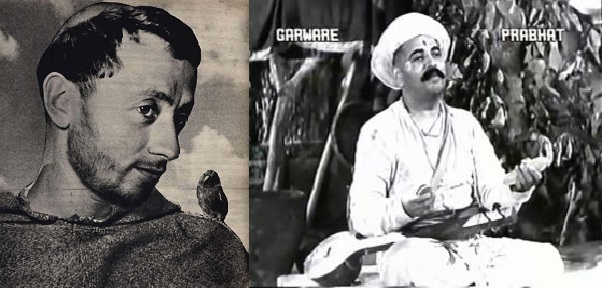

Both Francis and Tuka are offered by their respective film-makers to their followers and to us, as their audience, in their physiologies. Following the dictates of neo-realist cinema, both saints are primarily enacted by non-professional actors. Francis is played by a real brother who was a Franciscan monk, Nazario Girardi. An actual bhajan singer of hymns or abhangas, Vishnupant Pagnis, was chosen to play Tuka. Their integral biographical selves are crucial in authenticating their fictive presentation and representation of two of religions most enigmatic and popular saints.

As a result, the very process of performing as a saint is dispensed with all together because they are not professional actors. Performing, in fact, is simply replaced by being. Their presence, is enough to summon up the saints they are shown constantly evoking and re-evoking. There is no act/ing involved here, just one continuous be/ing!

In Sant Tukaram, the very pure offering of bhakti as devotion is conveyed by the way Pagnis, as Tuka, sings and dances his abhangas or hymns for Vithala, his God. It is not staged as a performance, either for the idol of Vithoba, which is before him in the temple or for his surrounding kirthankaris or singing and dancing devotees. Pagnis’s entire body and face is turned inwards. We see him moving his eyes, his lips, and his upper body to reach the Vithala who is within him. This is the God who is being woken up, the God that lies underneath his breath of singing words. These marvelous musical gestes are then brilliantly contrapunted (if that is the correct musical term I am grasping for) by contrasting them with those of his corrupt rival Salo Malo, who constantly plagiarizes Tuka’s abhanyas and presents them ostentatiously through the carefully rehearsed performative abhinarjaas or gestures of the popular tamasha entertainer.

We see this in the film’s very first abhanga or hymn “Pandurang dhyani/Pandurang-mani” (God becomes yours/when you constantly recite him in your mind). We see Tuka completely lost in the singing of it during the credit sequence. The utter simplicity and the genuine transparency with which he immerses himself in the hymn, seated with his eyes completely closed, is then sharply contrasted with Salo Malo’s exaggerated performing of it as his abhanga in Vithala’s crowded temple. Tuka’s solitary grace is replaced by Salo Malo’s excessive theatrics. Tuka’s humble clothing bears no ornamentation like Salo Malo’s embroidered attire. The verbal purity of Tuka’s utterances as they emerge from his lips are so far above Salo Malo’s dramatic falsettos, where, his pronouncement of the shabd or word dhyani, for instance, is literally suspended, merely for effect, by a theatrically created khatka or pause.

Similarly, when Tuka ends his abhanga or hymn with his customary signature of “Tuka mahne or “Says Tuka,” he utters this for Vithala’s sake. It is his direct address to his god with whom he has been having a personal and intimate discourse. But when Salo Malo punctuates “Salo Mhane,” it is addressed to his fawning audience. He, as performer, wants the verbal response of an “Ah” from them as an “appreciation.” God is nowhere in his horizon, and so there is a repetition of his verbal signature, this time essayed by one of his accompanying singers who actually intones “Salo Mahne” in a much lower octave in case some members of his audience have failed to respond to his master.

Tuka’s instruments too are very simple, usually a tal and a pair of chiplyas or castanets. Salo Malo, however, surrounds himself with two accompanying singers armed with a veena, a tal, with also a pakhawaj player on the side. God does not need such extravagant paraphernalia which introduces, instead, a false layer of spectacle. In true bhakti or devotion, all spectacle has to be avoided. It is a private enactment bearing only two witnesses—God and his devotee!

Tuka’s musical abhanga tradition is exemplified even by his wife, Jijai. When we first meet her, she is washing her buffalo and singing softly to the beast with the same kind of reverence her husband does when he sings to his Vithala. But her singing is interrupted by her crazy husband who enters her patio softly singing his Pandarang dhyani abhanga. She stops singing and flies into a rage because Tuka’s devotion to that “black god” has constantly ruined her household and driven her family to poverty. From her pragmatic point of view, her songs are only addressed to those, like her buffalo, who in its younger and more healthier years provided milk for their starving children. It does not have “a stone heart” as her husband’s “blackstone idol of Vithoba. But whenever we see her performing her chores for the family, she always does them willingly and lovingly by constantly singing to herself. It is bhakti or devotion of another kind, but it bears the same significance of purity.

Jijai’s singing is very effectively contrasted with the Salo Malo musical tradition. When Salo Malo hurries to his mistress, the courtesan Sundara, to declare the success of his “stolen abhanga” which he hopes will defeat Tuka’s popularity, he asks her to sing a lavani to celebrate this moment. Lavani songs celebrate eroticism in a bold and frank manner. They were usually performed by women who functioned outside the codes of decency and respectability like courtesans and professional singers and dancers. When Sundara sings her lavani, it is artificially rendered. It is a song that lacks any kind of integrity. It involves skills that are expected from her as a performer for which she will be monetarily rewarded. It is also a song that is expected to be rendered as an aphrodisiac—a musical foreplay resulting in the inevitable sex which is to follow.

Another theme that unites both films is the celebration of nature. “How good it is to stop doing, thinking and struggling and give it all up to nature, to become her thing, her concern,” muses the young doctor in Boris Pasternak‘s Dr. Zhivago. Kazantzakis‘s Zorba also talks about nature as that “divine whirlwind which can convert bread, water and meat into thought and action” in Zorba the Greek.

Both our saints follow in their traditions. The brothers in St. Francis…exist in perfect harmony with nature. It is as if they have internalized nature where man, bird, beast, grass, trees, rock, rain, heat, snow all exist as one. “Fire” is addressed affectionately and given a familiar male gender—”brother fire.” When Francis sees brother Giovanni beating the flames that are about to consume his tunic, he gently asks him, “Why do you want to harm brother fire?” Nature provides the brothers with the most appropriate space yo practice, on a daily basis, their ideology of “doing.” The brothers are never shown as being still, meditating, or being inactive. They are constantly doing something in nature, like building a hut, or collecting fruits and herbs, or fetching wood for the fire. “Doing (all the) things (that nature supplies) by oneself is a way of getting to know about life,” one of the brothers loudly proclaims as he happily goes about doing his daily tasks.

It is a ritual or what the Sikhs call, karseva, or work duty, like cleaning the porch, planting the corn where all the chores are done in the constant spirit of play.

Giovanni loves to play on the chapel bells inside one of the huts. Ginepro loves to play at swinging with the children. Nature brings out the child in them constantly and maintains, therefore, in them, a permanent state of wonder.

Tuka’s abhangas, many of them, spring from the very womb of nature itself. Some of them accentuate the seasons. Others give expression to nature’s instance of plenitude. When Turka’s wife feeds her child with bhakri or food, and then without eating a morsel, is shown taking the rest of the food to her wayward husband who is with his Vithala on top of a hill, we hear a very beautiful ashhanga or hymn in which Tuka celebrates all of nature’s beauty as he sings in praise of “the sun” and “the birds” who have returned to “their nests” in Viksha valli amha soyari vanachare/Pakshihi susvare alaviti.” This abhanga is there even in the Rossellini film when Francis gently asks “the birds” not to make “such a loud noise” while he is praying, and inspires them to “accompany” his prayers “with their songs,” so that God can receive both at the same time.

In The Flowers of St. Francis Tuka’s idea of bhakti or devotion is reaffirmed by Francis when he makes the important distinction between “words” theatrically preached in a “sermon” and “actions” genuinely “performed” to validate the “message” conveyed in the sermon. Francis privileges “actions” over “words” because it is in the process “of doing” that the brothers are schooled to discover the certainty of what they are being asked to do by God. “Preaching” with words in a theatrical way only draws attention to the self an Francis even provides Brother Ginepro (played by an actual brother, Severino Piscane) with a meaningful sermon, “Mbo, Mbo Mbo, I say a lot and do little” to train him to completely empty and forsake his self while preaching. It is this humility that saves Ginepro when he strays into the tyrant Nicolaio’s camp and undergoes excessive physical torment at the hands of his men. The confrontation between the tiny brother, dressed in simple robes with the benign expression of a smile on his face resisting all physical indignities and the tyrant’s enormous comic’s coat of armor set into motion by a complex system of pulleys clearly shows the victory of the brother achieved on the very “simplistic” and “essential” terms of Francis’s doctrine of bhakti. The tyrant’s ferocious grimaces and outlandish threats have no effect on the tiny brother’s powerful and sustained impassivity and it is in this transaction that the tyrant and Ginepro learn Francis’s important lesson that “souls are saved by example and not by words.” When Ginepro, in fact, confesses that he is “a great sinner” in the presence of the tyrant, the articulate Benedictine, one of the tyrant’s wisest counselors, asks aloud, “If this is Ginepro, then what must Francis [and by extension, Tuka] be like?”

Another quality of bhakti that both saints share, is that of “giving.” Brother Ginepro often returns to his brothers after having “given away” all his clothes to the poor. When one of the brothers complains that he “gave” his own clothes to Ginepro, who in turn, “gave” them to a poor man, he is gently reminded by another brother, with a quotation from the bible: “he was naked when we found him, and so we clothed him.” Tuka also practices this “giving” ideology which is wonderfully illustrated in the scene when we see him walking through a village street armed with a large bundle of sugarcane given to him for services rendered by a grateful farmer. So wrapped up is Tuka in his Vithala, that he is literally unaware of the little hordes of children who creep up all around him and plunder him of his entire bundle leaving him with only two sticks of cane that he hands over very happily to his very poor and starving son and daughter who are absolutely delighted by his last ounces of generosity. The same generosity is displayed when God creates the miracle of surplus grain at Tuka’s door, and Tuka invites the entire village of Dehu to take “generous” portions of “god’s gift” that was given not to him alone but to them as well. And when they come and collect the grain, Tuka accompanies their actions to the Bolava Vithal/Karava Vithal abhanga or hymn (when you utter God in your words, God is enacted in your actions). This is indicated marvelously in the scene when the Shastri arrives to interrogate Tuka in Dehu. As he rides into the village, arrogantly erect on his Brahaminical saddle, he is immediately cut down to size by the entire village which is shown completely engrossed in the performing of its daily tasks. And these chores are being attended to joyfully because they are accompanied by the vibrant singing of Tuka’s abhangas. As the camera tracks the Shastri’s riding from the foreground of the screen, we see an entire palki or procession of villagers working dynamically.

Here, the usual monotony and alienation of non-productive labor is replaced by a joyful celebration of work that is actually maintained in the true Franciscan spirit of finding yourself through your “actions” which the “words” of Tuka’s abhangas are making them accomplish, almost like a miracle.

Tuka, however, never claims any acknowledgement of the several miracles that Sant Tukaram, as a film, is littered with. Since the film language of neo-realism would, cinematically speaking, force the film-maker to gravitate his film more toward the instance of a Lumiere created realism, the Melies magical intrusion of chamatkaars or miracles in Tukaram’s text, at first, seem ideologically unnecessary. However, on closer examination, we realize that the offering of these miracles de-establish, rather than, reinforce the idea of the fabulous because they are presented in a very naïve, crude, and primitive way solely on cinematic terms. Look at the subjects that are chosen to perform these miraculous acts: Vithoba’s stone idol is made to dance very awkwardly in its chamatkaar reincarnation of a flustered little boy; Krishna pouring grain from the sky, once again, is a very clumsy boy; the goddess who emerges from the Indrayani river with Tuka’s drowned bundle of verses is a stagy, corpulent, overpainted ‘extra’ with four mechanical arms; even the chariot that carries Tuka to vaikunth or heaven is a clumsily made studio prop of a gigantic hairy bird. The fabulous is constantly undermined by such very imperfect primitivity, but on the other hand if the miracle “boys” consistently resemble Tuka’s very conspicuous, awkward nature of childlike innocence, the miracle goddess comes pretty close to how a native Dehu villager would visualize her in his primitive imagination, nursed as it was, on tamasha actresses performing similar roles in their popular traveling theatrical productions they would have witnessed.

Hence, the film does achieve a hybrid mix of the two strands of cinema, without in any way, disturbing its over all neo-realist presentation. A good instance of this is Sant Tukaram’s final scene where Tuka is shown taking leave of his earthly existence after announcing it to the entire village in his wonderful abhanga: Amhijato or I am departing. His marvelous departure on that gigantic bird to Vaikuntha or heaven is wonderfully undermined by the pathetic but realistic cry of his wife, who with her feet planted firmly on the ground, is telling her airborne husband that she will expect him “back home” for “his supper with her and the children” after his encounter with his Vithal up there!

Rossellini’s St. Francis film achieves a similar magical-realist ending. When the brothers ask Francis where they should proceed to spread their essential messages of God, Francis has them spin around and around till they get dizzy and fall to the ground. Whichever way they fall is the direction determined for them to follow. It is important to note that Rossellini holds the camera completely immobile when he records this marvelous scene. He does not allow cinema’s technology to interfere with the miraculous paths that the individual destinies of each of the brothers will determine for them. The whole landscape is spread out behind them and it is into the landscape that we see each of the brothers finally disperse after taking leave of each other. As they become smaller and smaller and fade into the distance, Rossellini tilts his camera to Vaikunth and holds it on a shot of moving clouds crossing the sky. As this image fades, the final, divine transcendence, has been achieved, for in that sky, somewhere, there is also a gigantic bird carrying a Vithal wrapped saint to his Vithal or God.

![]()

Darius Cooper teaches Critical Thinking in the Humanities at San Diego Mesa College, California, USA. His essays, poems and stories have been widely published in several film and literary journals in USA and India A sample: Between Tradition and Modernity: the Cinema of Satyajit Ray (Cambridge University Press).In Black and White: Hollywood Melodrama and Guru Dutt(Seagull Publications).Beyond the Chameleon’s Skill (first book of poems) (Poetrywalla Pub).A Fuss About Queens and Other Stories (Om Books). Read his review of Kedarnath Singh's poetry 'BETWEEN THUMBPRINTS AND SIGNATURES'.

Leave a Reply