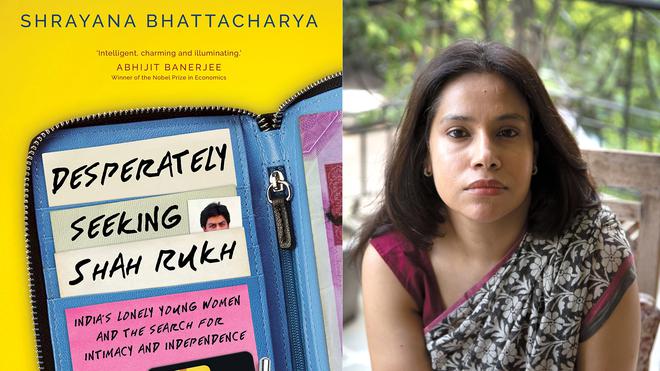

Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh Khan: India’s Lonely Young Women and the Search for Intimacy and Independence. Shrayana Bhattacharya. HarperCollins India. Nov 2021. 464 pages

“Let me be clear — there is no meaningful dimension of well-being on which men and women are equal in India. None. Within each class and caste bracket, women fall far behind men.”

“Fifteen years since I unknowingly began the research that culminated in this book, for the women I’ve followed and chronicled, Shah Rukh remains a spiritual timeout from the alienation, irrational trade-offs and determinism of modern life.”

These are two of the author’s statements that sum up the premise of this fascinating book. A Google search for Shrayana Bhattacharya tells us that she is an Economist in the World bank’s Social Protection and Labour unit for South Asia. Her research is focussed on the areas of “urban bureaucracy, social protection and informality”.

Bhattacharya’s earliest jobs were with the women’s trade union, SEWA, founded by Ela Bhatt in Gujarat, which has done pioneering work in organizing women of the “informal” or “unorganized” sector: a category that covers the large majority of working women in India. She later worked at the Institute of Social Studies Trust, Delhi founded by the famous economist D.T. Lakdawala. She was exposed to the ideas of some of the best minds studying the poor and deprived in India. She mentions the influence of some leading feminists, among whom Devaki Jain and Nirmala Bhattacharya are named. She says she has studied gender and development, being “possessed” by words like ‘patriarchy’ and ‘agency’ which, in this book, she tries to shake off.

From these jobs she moved to the ILO. Her later career was in working for research companies and international agencies affiliated to the UN and the World Bank.

The structure of this 500-odd page book, however, moves us in an opposite direction. The book is a sociological study that takes us through case studies of many women of different classes and social locations, with their Shah Rukh Khan fandom being the thread that ties them together. She begins with stories of women from more affluent backgrounds, women whom she encountered later in her career, and only towards the end of the book talks about women of the urban slums or small North Indian towns, and migrants from Jharkhand.

Maybe she does this because the loneliness and unhappiness of the latter sort of women, who live under constraints of family, caste and a misogynistic social environment, is only to be expected. It is, however, somewhat surprising that the examples she gives in the beginning of the book, women with some degree of privilege in terms of education, wealth or social location, who have fought and partially succeeded in attaining their ambitions, are also suffering from a deep loneliness and seek solace in fantasising about Shah Rukh Khan. Bhattacharya also tells us that she herself is a Shah Rukh Khan fan, which is the reason why asking her ‘respondents’ about their favourite actor is, for her, a useful and pleasurable way to get them to open up to her. She has picked out those who answered – Shah Rukh Khan — for more conversations about their dreams.

Halfway through my reading of this book it struck me that, in charting economic changes —in employment, availability of consumer goods and the expanding use of telecommunication devices —in the period, roughly, from 1995 to the present, and relating them to contemporary media phenomena (and SRK, undoubtedly, is such a phenomenon) Bhattacharya is giving us a sequel to a story that was charted by Arvind Rajagopal in a book published twenty years earlier. In his Politics after Television, Rajagopal traces how the spread of television sets into middle-class homes in the 1980’s (itself an outcome of the gradual and selective opening up of the Indian economy during the 1980’s, and the screening of the great Hindu epic, the Ramayana, as a television serial), set the stage for a transformative chapter in Indian politics. The Bharatiya Janata Party, until then a small player in electoral politics, took the cue from this to project a Hindu identity as the definitive unifying factor of the Indian nation. L.K. Advani’s rathyatra in 1990 put fire into the movement for reclaiming the site of the centuries-old mosque known as the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya, in Uttar Pradesh. This was the BJP’s answer to arise in consciousness of the Bahujan or middle castes among Hindus. In 1992 a mob of kar sevaks (servers through action) demolished the Babri Masjid in broad daylight in the presence of national and international journalists.

Rajagopal’s book was pioneering in the connection it drew between a media event and its political reverberations, tracing back the media phenomenon to the widening consumption of television sets.

It seems to me that Bhattacharya is giving us the next chapter of the story, though her focus is not on politics but on sociology, on the changes in women’s lives between 1995 and 2020, and the emotional tensions that these changes generated.

I remember 1995 as a kind of turning point. The further opening up of the Indian economy under IMF recommendations was beginning to show its impact on people’s life and their culture. I was living in Aurangabad, a small town in Maharashtra at the time, and I remember writing a small piece on how Hindi film songs were suddenly becoming more tuneful. After a flourishing of Hindi film music around and after independence, when composers drew on folk songs, western tunes and the spirit of becoming a new free nation, there was a hiatus during the 1970’s and 1980’s, when, to my ears at least, cacophony ruled. And suddenly into the 1990’s Bollywood songs blared out by autorickshawallas were not hurting our ears. A.R. Rahman., a young man from Chennai who converted to Islam after his father’s death, started with writing ad jungles and graduated to Hindi films; he is now an accomplished composer of international repute. Many of my friends, my contemporaries, did not like his music. But he definitely started something; and now Hindi film music was not dominated by a handful of ‘music directors’. There was a life, a variety, a new creative spirit. And for all my criticism of the new economic policies, I recognized that there was something new in the air.

Shah Rukh Khan made his first films in the early nineties. They say he modelled himself on the earlier movie star Dilip Kumar, a Muslim actor who had had to take a Hindu name in order to be acceptable to a wider audience. My brother Sudhir, much more a film aficionado than I ever was, once remarked that Dilip Kumar was the only film hero of his time who actually romanced his heroines. The others were too much in love with themselves and their own image. Many of the women interviewed by Bhattacharya said something similar about Shah Rukh Khan. Of his star contemporaries –the three Khans are still talked of in one breath – Salman Khan had a ‘bad boy’, macho image, while Aamir Khan was too intellectual, and, in Bhattacharya’s view, catered to the pretentious, jhola-swinging liberal left.

This blanket dismissal of left intellectuals is very much a 21st-century custom. But she makes her point. Shah Rukh was the one who fuelled young women’s romantic dreams.

SRK started acting in films in the early 1990’s. Baazigar was an early film noir, and his modern fangirls are mostly not too enamoured of his role in that film. I remember seeing some SRK films in this period, and I was far from being a fan. I felt, in fact, that his very popularity was doing something to the medium of Hindi cinema that I did not really welcome. I didn’t really explore my reasons for this dislike at the time, except maybe saying that his exaggerated acting was more suitable for the stage than the screen. But today I would say something like this: besides romancing his heroines, SRK is always also romancing the camera. He positions himself as a star. Even in his earliest roles, he is already part of an elite. He does not allow the camera to romance him, or portray him; he is ready-made. This means, to me, that he is doing a kind of violence to the medium.

Of course, it was the 1995 Dilwaale Dulhaniya Le Jaayenge (DDLJ) –The ones with heart will carry away the bride — that really made SRK into an icon. The film has become a classic of its genre. Here is a quote from a newspaper from two weeks ago (February 2023)

`Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge` was a game-changer in the romantic genre in Hindi cinema. From its plot to cast to the music, the film is classic and cherished by people across age groups. On Thursday, Yash raj Films, the production house behind the film announced that the film will be re-released in national cinema chains across the country for a week.

The occasion for this was the unprecedented success of SRK’s latest film, Pathaan. In the time since Bhattacharya’s book was published, Shah Rukh Khan has become a target of strident right-wing voices resentful that a Muslim actor can be so universally loved. There were calls for ‘true Indians’ to show their patriotism by boycotting the film.

In spite of these, spectators in India and abroad flocked to cinema theatres to see the first mega blockbuster since the Covid-19 lockdown.: This week there is news that the movie’s takings have crossed a hundred crore (one billion) rupees in record time.

DDLJ is the SRK-starrer most frequently referred to by Bhattacharya, and by Bhattacharya’s interviewees. In 1995, the opening of markets had brought new aspirations for consumer goods and fashions, and a desire to see the world outside India. The producers of DDLJ gave their audiences a romantic fantasy that starts off in London and Switzerland, then moves to the heartland of rural north India. The bride is a young woman who has been brought up in London but has agreed to an arranged marriage. She wants to have a last adventure before she is tied down, and meets the hero played by SRK, who indulges her desire for adventure but also protective when she needs that. Bhattacharya notes how the romantic scenes shot in Europe cater to the fantasies of a class that is becoming aware of global lifestyles but can never hope to afford a trip abroad.

The television of the 1980’s whose influence is traced in Rajagopal’s book, afforded just one channel. But after the economic reforms of the early 1990’s, by 1995, television in India covered more than 70 million homes giving a viewing population of more than 400 million individuals through more than 100 channels. It is true that most families could not afford their own TV sets, but, in the urban slums and in rural villages and small towns, neighbours would gather at a TV owner’s house to view films and favourite programmes.

DDLJ was remarkable in that it also enshrined a respect for traditional ‘Indian’ values. The hero and heroine have declared their love for each other, but the SRK character pledges to win the blessings of his beloved’s family. Among the scenes most liked by SRK’s woman fans is the one where he enters the kitchen and helps the heroine’s mother with cutting vegetables. This is what Bhattacharya’s lonely women dream of: a man who will treat them gently, who easily helps with household chores.

Shah Rukh Khan went on to play different roles in his subsequent films (he was making about five films a year), but the fangirls accept even his negative roles: he is SRK, he has already established himself as a certain kind of man. Writing of one of his worst films, in which Bhattacharya feels that the script doesn’t treat the woman with respect, she finds that ‘there are flecks of vulnerability in the leading man’s eyes. What a relief’.

Many of the fangirls, especially those who speak English, watch interviews with the actor, and these interviews reinforce SRK’s fanworthy image.

He is one Bollywood actor who is not touched by scandals; he is reputed to be faithful to his wife. His screen personas and his real-life persona seem to merge, making him an even more desirable object of fantasy. He is unabashed in claiming his stardom. That absence of modesty makes him sound even more genuine.

Bhattacharya uses this adoration of Shah Rukh Khan to get the women she interviews to speak about the more personal aspects of their lives. As I said, she begins the book by discussing women from similar backgrounds to her own. She has already told us that she is a genuine SRK fan herself. And so, the first chapter that narrates stories of lonely women has the title “Elite Composites”, and here she gives us canned versions of similar narratives: women who get a good education, good jobs, then inevitably enter a marriage or a relationship and are disappointed by the experience. Some have ample domestic help to lessen their chores, but still end up tied to an unfulfilling routine and high expectations. The other two stories in the beginning part of the book are those of a woman who asks Bhattacharya to refer to her as just ‘The Accountant’’. This woman comes from a middle-class family, but, because of her mathematical skills, manages to complete part of the course for chartered accountants. Family and financial constraints prevent her from becoming a fully certified chartered accountant. Bhattacharya throws in a few facts: in 2015, there were 300,000 registered chartered accountants in India, only 21 per cent of whom were women. But The Accountant finds remunerative work, and likes the flexibility of working hours, the ability to work from home (even before the pandemic made this a common practice) Women find a little wriggle-room in their highly restricted lives and they value the freedom that they manage to negotiate. But in the end, even for these relatively privileged women, it is not easy.

Bhattacharya inserts a few facts of this kind from time to time, and the economist in her gives us figures. She talks about the prevalence of suicide among Indian women, about how job opportunities for women are shrinking overall, and how more women than men lost their jobs during the pandemic.’ She weaves in words like ‘agency ‘and ‘patriarchy’’, but wants to keep her distance from the usual feminist theorizing. She is searching for some truth — but where is it to be found?

As I mentioned above, it is only towards the end of the book that Bhattacharya tells us about the women from much less well-endowed families whom she studied in the surveys she did for SEWA and the ISS Trust. Three women, all SRK fans, together with their daughters, are selected for detailed discussion. The first is Zahira, who earns money rolling incense sticks in a work-from-home arrangement in Ahmedabad, and later becomes a SEWA organizer.. Bhattacharya is familiar with the research on these work-from-home arrangements which poor women get into because it is easier to manage their household duties and keep an eye on their children while they work. The rates of pay are abysmally low, but still their earnings give these women a certain degree of freedom. A woman from Rampur in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh is able to keep the family going when her husband loses his job. Women from the even more economically backward state of Jharkhand migrate to Delhi for work; all they find is domestic service, but they set up a network informing their friends and relatives about families that treat their domestic help well.

These stories engage us; a reader like me is familiar with the scenario she unfolds, but the details are fleshed out in an interesting way. In all this, the women use the freedom and the money they have control over to feed their SRK fandom. The electronic devices are now different from the black-and-white televisions of Arvind Rajagopal’s book.

In fact the technology is changing faster than the attitudes of male family members who frown on the SRK obsession. The women, helped by their daughters, manage to keep one step ahead.

Bhattacharya returns to some of the women of her earlier interviews. She mentions the changing political environment with her trademark style of accurate facts inserted in a throwaway style, as if she is really refusing to thread them together into any of the accepted ‘theories ‘or to offer her own. What interests her is something I too have noticed in my own travels: women in unlikely environments, in small towns where patriarchal attitudes are still largely unquestioned, in metropolitan city slums, are looking for freedom in ways that are usually not discussed; they band together and negotiate, squeeze out some freedom from the constraints of duty and the confines of the family. They find venues for social mingling. But , she tells us, towards the end of this massive volume, young women today also want intimacy in sex, they want to dress well, to enjoy life. The women are seeking to find a balance, in Bhattacharya’s alliterative phrasing, among the three forces of “Market, maryada (or modesty) and modernity. Films are a large part of the means to do this. Shah Rukh Khan has managed to feed the dreams of women over three decades. What will happen as he ages? He is already in his late fifties, but the latest film Pathaan still seems to have the magic. Among the newer actors in Bollywood, Bhattacharya talks of Ranveer Singh, who has adopted a funky persona with an outrageous style of dress; he recently posed in the nude and the pictures went viral drawing much vilification on his head. That love is a disease of sorts,

But Bhattacharya tells us, maybe the technological divide is widening, perhaps films are no longer as important as they used to be. There are multiple sources of images that cater to the fantasies of young men and women. Bhattacharya is aware of an underlying ubiquitous misogyny that sometimes breaks into violence.

She makes a trip, a kind of self-conscious pilgrimage, to SRK’s home ‘Mannat’on his birthday (her second such visit, after many years), but finds that the crowds outside the mansion are largely male and the atmosphere is not friendly to women fans.

After a chance encounter with a girl taking part in protests around the 2012 brutal rape of a young woman in Delhi, Bhattacharya visits her home and has a most unpleasant encounter with her brother, a young, rich, entitled Jat who spouts the most virulent sexual innuendoes when he sees this poised modern woman with his sister.(We are also treated to a brief discourse on the social journey of the Jats, a dominant non-Brahmin caste in the agriculturally affluent northern states of Punjab and Haryana.)

The final chapter of Bhattacharya’s book has the title Loveria, which is the name of a song from the 1992 SRK-starrer Raju Ban Gaya Gentleman. I happen to know something about this song, a knowledge that caused me to feel a bit rattled as I read this chapter title. More of that later. While the coinage Loveria implies that love is a kind of disease, in this chapter Bhattacharya muses on her conjectures and premises (not hypotheses or theories). She feels that Indian feminists have not paid enough attention to women’s emotional needs; that is why she has chosen to focus on the power of romantic fantasy: to alleviate the drudgery of everyday life, to inspire, to colour dreams which are an important part of living.

Fandom is also a kind of love. And love conquers all: Meenal, the daughter of the Muslim SEWA activist from Ahmedabad, is at first a little upset that SRK has been silent on the ruling regime’s moves to target the citizenship of Indian Muslims, through the Citizenship Amendment Act of 2019. But she is quick to forgive him when he makes a bland comment that avoids actually mentioning the new law: ‘He has said something, he will speak out later’. This is one of the rare mentions in this book of how the present regime goes after Muslims.

A fantasy icon that can be clothed with all the qualities that women desire from their men: SRKconsciously presents himself as an icon, plays to these fantasies. And he becomes a template for mainstream Hindi cinema. He usually appears as upper-class, often sports a janeu, the sacred thread of Brahmins. He may appear in many different roles, but he is always larger than life. His very overwhelming popularity crowds out the possibility for Hindi cinema to make films about real, ordinary people. I enjoyed the film Band Baaja Baraat starring Ranveer Singh (named by Bhattacharya as SRK’s successor) which centres round a middle-class man and woman trying to profit from the wedding management business. But his later film, Gully Boy, even though set in a Mumbai slum and telling a story of creative aspirations, was to me disappointing, somehow falling prey to the ‘larger than life’ template.

A small personal postscript: but first I must say I enjoyed this book. It made me look at my own compromises in life, my own fantasies, my experience with the collection and presentation of data, of feminist discourse. It even has a set of tables at the end which appealed to the long-retired economist in me.

PS: When I was living in Aurangabad, I with my poet husband Tulsi were friendly with Bashar Nawaz, an Urdu poet . we visited him from time to time. On one visit he greeted us excitedly: after a long gap, he had been invited to write lyrics for a Hindi movie, something he used to do quite often. The film was Raju Ban Gaya Gentleman, and he read out the words to us. Ultimately his song, Loveria, turned out to be the most popular one from that soundtrack. But when I googled the movie, Bashar Nawaz’s name did not appear as one of the lyricists. Here was a poet, well-known in this mofussil town, living well away from the limelight, but playing a part in creating the large-scale dreams and fantasies of Bollywood. Gentle poetic irony.

******

Till recently, Professor at the Advanced Centre for Women’s Studies, TISS Mumba, Wandaana Sonalkar has translated various Marathi texts into English including Urmila Pawar and Meenakshi Moon’s book on Women in the Ambedkar Movement, Zubaan, New Delhi and some short fiction and poetry. Her translation of the autobiography of the Dalit communist activist R.B. More was published by LeftWord Books as "Memoirs of a Dalit Communist: The Many Worlds of R.B. More" in 2019. Her autobio-polemic "Why I am not a Hindu Woman: a Personal Story", was published by Women Unlimited, New Delhi, in 2021. She is a member of The Beacon’s Panel of Editors

Also read translation by this author of Baburao Bagul’s THE PEOPLE ON THE GROUND

Listening to Shrayana Bhattacharya’s interview as a podcast (Cyrus Says) on the same topic is fascinating. Now with Wandana’s review of SB’s book, reading it becomes an imperative.

Wandana Sonalkar’s review of “Love and Fandom in the Time of Loveria” explores the intersection of love, fandom, and popular culture.