AN UNFINISHED SEARCH One Lineage, in One Village, through Three Nations. by Rashmi Narzary. Paperback. Pippa Rann Bppks. June 2023. 318 pages

Chapter I : The Year Twenty Seventeen – Malegarh War Memorial

B

ut I had tended to those graves, huzur, I planted the flowers around them, and I pulled out the weed and grass along the sidewalks. So that the martyrs there may lie in peace. I tended to each one of those graves, like each had my grandfather’s abbajaan resting there, I don’t know in which. So, I tended to each. Please, huzur, let me in!’ he pleaded.

It pained the soldier to see the eighty-five-year old man begging him thus to let him in. Asman Hazratkandi would be about his grandfather’s age. Or even older.

‘Please, Asman,’ the soldier said, placing an apologetic hand on Asman’s stooping shoulder, ‘not today. The ministers will be here any moment.’

‘Yes, I know,’ Asman replied, ‘and it is them, at least one of them, that I need to please ask…’

‘But they won’t be alone. They will be surrounded by lots of people, Asman, all very important people. Senior officials, bureaucrats, police, political leaders, so many of them. From both India and Bangladesh. You won’t even be allowed anywhere near the ministers, let alone speak to them or ask something,’ the soldier tried to dissuade Asman.

Asman Hazratkandi thought for a while and then asked again, ‘Then can’t I even be allowed to speak to anyone of those big officers, huzur? Someone? Anyone, please?’ Asman looked at the hillock ahead.

The otherwise tranquil Malegarh hillock, that gave those lying there in eternal slumber all the solitude they ever needed, wore a festive look today. The place was teeming with Border Security Force personnel, State police officers of Assam and personnel from all ranks of the Indian Army. Because the hillock was on the outskirts of the town of Karimganj, lots of people from the nearby villages too had gathered to see what was unfolding. These were people from both sides of the Indo-Bangladesh International Border at Sutarkandi. Some came to have a look at the ministers; some came all dressed up and ready to appear on television because they heard that the media would be there to ask random questions to random people about the Malegarh Monument. Some stopped just as they were passing that way. For whatever reason, the place was crowded, and the lone narrow road was getting congested. Up on the hillock, where Asman Hazratkandi’s grandfather’s father lay, organizers had put up garlands of fresh, bright yellow marigold on the black granite plaque that read,

In the memory of those who sacrificed their lives

In the great Mutiny of 1857,

For the freedom of the Country

Asman Hazratkandi, however, could only read the Bengali translation of these words, written above the English words. He forgot count of how many times he read those words, the ones written in Bengali, running his fingers over them. On those occasions, he had unrestrained entry into the site of the monument. He had guarded the monument from stray goats and miscreants, had warded off boys and men who came in with boards of dice and bottles of rum to sit in the solitude there. He had guarded this monument like it was his family’s heritage. But today, guards stopped him from entering.

Asman Hazratkandi pushed his cycle slowly across the road towards the narrow patch of grass that grew all alongside the road. His cycle didn’t have a stand. So he put it gently down on the grass as if putting a child to sleep. Because his were hands that tended to graves, and grew flowers around them, they were always gentle with everything, living or not. He sat down on the grass next to his cycle and watched the preparations for the celebrations at the Malegarh hillock. The hillock which had the answer to the one question that stayed with him, unanswered till today, since that first time when his grandfather Anjaan Hazratkandi brought him to see the graveyard. Asman was then around fifteen years of age. But he remembered well. All that his grandfather had said. He recollected his grandfather’s eyes and the way his voice choked often during their conversation that day at the hillock.

The soldier from the Border Security Force too had been slowly walking up and down the road keeping a watch. He now walked up to Asman and stood near him. ‘You know, huzur,’ Asman Hazratkandi found courage to talk, ‘it was in the year 1947 that I first came here. With my dadajaan. My grandfather. See that plaque there?’ he said, gesturing towards the garlanded plaque. The soldier turned to look but the view was obstructed by all the people around it. ‘That plaque was not there at that time,’ Asman went on, ‘the grave slabs too were not here. But the memorial was. There was no boundary wall, no, nothing much of a monument. Even that blue board, you see huzur? With the story of the valiant Malegarh martyrs? No, even that wasn’t there. Very few people knew about the significance of this place then. Even I didn’t think much of it those days. But my dadajaan did. Because he was in search of his father. His father’s name. He was in search of freedom of a different kind, huzur, he was in search of freedom from being without an identity.’ Asman ran a hand down his grey beard as he looked up at the skies. ‘You know what dadajaan had said to me that day, huzur, standing there on the hillock?’

‘What did he say?’ the soldier asked.

‘He said,

Asman, now on, where we have been living is no longer India. It is now Pakistan.

And, huzur, I asked him if we would have to move away to some other place, if we were shifting house.

Then dadajaan had said,

No Asman, we will remain where we are. It is only the nations that have come and gone by us. Our address has changed. Not by a street, a village, or a district. But by a country! By a country, Asman, by a whole country, even though we remain just where we are. The same skies above us, the same ground we walk on, the same Dooni streamlet that shall continue to flow into the Sonai river that meanders through the land, Asman, the same village of Hazratkandi, the same district of Sylhet. Yet, it will be a different land. A different country….’

Asman Hazratkandi thought for a while before speaking again, ‘I remember my dadajaan’s voice choking when he said all of that, huzur, he had a lump in his throat which he didn’t want me to see and had a bigger burden on his chest. But I saw both the lump and the burden. As the nations changed again and again, that lump, and that burden started to grow on me.’

‘How old was your grandfather then, Asman?’ the soldier asked.

Asman looked at the far horizon and stared at it for a while. As if recollecting. Or calculating the years.

Then looking up at the soldier, he said, ‘How many years would that be, huzur, if he was born in the year of the mutiny?’

The soldier thought and said, ‘Mutiny … eighteen fifty-seven … Wow! That would be ninety years! He lived well, Asman, your grandfather lived well!’

‘But not long after that visit to these graves. He passed away soon after,’ Asman replied.

‘Oh! And did you come to these graves again soon after he passed away? After your grandfather?’ the soldier asked. He was starting to find it all very intriguing.

‘I did. With my abbajaan a couple of times. We would just walk around here and rake in the fallen leaves in winter and pile them in a corner and burn them. ammajaan had once sent a few saplings of the gulmohar with us, and we planted them among the graves and along the periphery of the site.’ He paused. As if wondering if the soldier still had any interest in listening. It seemed he had.

‘Didn’t stray goats and cows eat up the saplings?’ the soldier asked, curious.

Encouraged, Asman Hazratkandi went on, ‘Abbajaan brought fine, thin sticks of bamboo from home with him and made fences with them around the saplings. Then he started to visit this place once every day because the saplings had to be watered. He brought a bucket with him and in it fetched water from the ponds over there to water the plants. Once the roots grew steady, they no longer needed watering everyday. But it had become a habit with abbajaan to tend to them. He sometimes collected cowdung from the fields nearby and sprinkled them around the base of the plants.’

A child was running towards the approach lane and the soldier hurried across the road to turn him away. He stood near the lane for a while and then once more crossed over to Asman.

‘So, your father too used to tend to the graves?’ he asked Asman.

‘It started from those saplings ammajaan had sent. Yes. Once the plants were on their own, abbajaan, by habit, started pulling out the weeds. Then one thing led to another, and he started to plant flowers in the whole graveyard. Huzur, actually, it was my dadajaan who used to tend to these graves. Then when age caught up and his fingers started shaking and his hands no longer obeyed him, he stopped coming here. He had to. Because even if he wished to, he couldn’t. No, no more.’

‘So, it was then that you took over? He asked you to?’

Only then, faced with that question, did Asman Hazratkandi realize that nobody had asked him to tend to these graves of the martyrs. He was simply drawn to them. To tend them. Very lovingly. Very possessively. As one would his identity.

‘No, huzur, nobody asked me to. It just came to me,’ Asman replied.

The soldier suddenly heard a commotion and had to walk away, towards a group of young men and women alighting from a van equipped for live-telecast of the proceedings at the function. Their equipments were the cause of some fuss with the security personnel and the reporters had some issues walking through the metal detector placed at the bottom of the steps, at the entrance to the monument. The soldier from the Border Security Force walked in to help his fellow guards. Once the matter was settled, the soldier looked for an opportunity and slowly, though alert and never neglecting his duty, walked up once more to Asman.

‘When will they arrive, huzur? The ministers?’ Asman Hazratkandi asked him.

‘I don’t know, Asman, I wasn’t informed about that. I am only to guard the place and see that everything is safe for the VIPs and the people gathering here. This place, the Sutarkandi border area, has always been a matter of immense security concern, being an international border area. There has been a lot of illegal border crossing, of both human and cattle,’ the soldier took pride in his superiority of knowledgeabout international affairs, even though it was confined to the Indo-Bangladesh International border at Sutarkandi. But he wondered how the old, grave-tending Asman Hazratkandi would find that out.

‘I have known Sutarkandi since the times when it was just one land, huzur,’ Asman said, ‘then I saw the land being split from one to two, and now here I am, living long enough to see one part of that split land,’ Asman raised a hand motioning towards Sylhet in Bangladesh, ‘first made a part of one nation, then detaching itself to be on its own. Huzur, I was born on that land. Since then I have been stayingon the same land which was once known as India, then came to be called Pakistan. East Pakistan. And now it is Bangladesh. But it remains the same land. Isn’t that strange, huzur?’ And Asman Hazratkandi himself answered that question, ‘Yes. It truly is. That some stretch of land should go through such phenomenal change of address, despite being rooted just where it had always been. And here I am, one man who has lived through it all and seen all of it change. By just remaining there, at that same place, growing old where I was born. Being rooted, yet I know not about my own roots, huzur. Earlier when I used to come here with my dadajaan and then with my abbajaan, I didn’t have to write my name on the register at the Sutarkandi Border Security Outpost. I didn’t have to write anything while crossing back as well. But now I have to. At the crossing, under that imposing, green board made to stand tall enough to cut into the skies, to separate it into the Indian sky and the sky of Bangladesh.’

*******

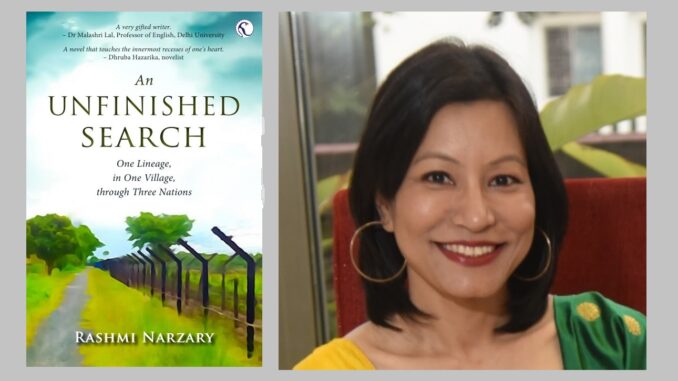

Sahitya Akademi Awardee for English Children’s literature in 2016 for her book ‘His Share of Sky’, Rashmi Narzary is an author, creative writing mentor, and independent editor. She has worked with Late Dr. Bhabendra Nath Saikia’s award winning Assamese works. Presently, Narzary is the Joint Secretary of the North East Writers’ Forum

Leave a Reply