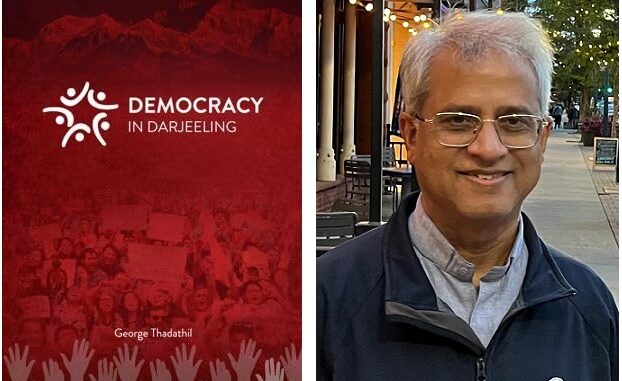

Democracy in Darjeeling. George Thadathil. Salesian College Publication. New Delhi, Siliguri and Sonada, May 2023. 275 pages Rs.950/- USD50/-

I

n the introductory chapter ‘Defining Democracy’ in his book Democracy, writer and Reader in Politics at the University of Sheffield, Anthony Arblaster points out very meticulously:

“Yet as soon as we start thinking seriously about what democracy is, what the term means, and has meant, some healthy doubts will begin to cloud this mood of self-congratulation. For democracy is a concept before it is a fact, and because it is a concept it has no single precise and agreed meaning.” (Arblaster 3)

As a concept which is closely related to autonomy, the West’s concept of democracy has often been undermined and generalized. The key to understanding how democracy is conceptualized, implemented, and interpreted is to gain an understanding of how it is conceptualized and implemented according to spatial, temporal, geopolitical, and regional discourses. George Thadathil’s Democracy in Darjeeling is both an inquiry and a repository of research-based outcomes that highlight fresh insights about Darjeeling’s society, history, culture, democratic ideals, and religious pluralism. The lucid description and cogent arguments about National aspirations and regional autonomy in Darjeeling remain at the core of discussion in the introductory segment of the book. It is the writer’s goal to generate a universal streak of indigenous rationality by analyzing the socio-philosophical perspectives that drive political and community goals. Since imperialism and cultural colonization have had such a profound impact on Darjeeling for such a long time, nurturing and strengthening the community’s autonomy toolkit has become an indispensable part of ensuring their survival. As Thadathil examines the concept of autonomy, identity, and equality, he points out:

“…[A]utonomy aspirations are linked to and flow from the desire for defining identity. Definition of identity is not merely a social or only a political programme. Underlying it are psychic and philosophic implications.” (Thadathil 8)

What defines the underlying currents and redistribution of the theory of democracy among the people of the hills? What about the dominant communities and the marginalized ones? How does one dissect the demand for autonomy by the hill people and the small associations that are formed? Do these associations spearhead the course of further movement to ensure democracy in Darjeeling? There can be these and myriad other questions about the designation and enjoyment of autonomy by an individual or a larger community of people. As the discussion moves further, the author enumerates the different modes of language in which the people speak, and how there was a clarion call to introduce ‘Nepali’ as a type of communicative tool first as a medium of instruction in schools and then as an official language of the hills. It is true that the purity, efficacy, and singularity of any language erode through time, as new discursive formations, diverse layers of dialect, and indigenous formations create a multilayered concept of democracy. If we consider globalization in a broader sense, with far-reaching repercussions of national and regional trajectories that thrive on plurality and cultural binaries even for the tiniest of communities, we can see how the purity of language becomes mythological over time. Since Darjeeling has grown in terms of tourism, tea, and lumber throughout the years, the flood of regional, national, and global tourists has had an impact on the transmission of language. The author’s sharp tone, descriptive articulation, and clarity of expression kindle the reader’s interest to know more about how the process of social identity has an overall discursive formation and affective dimension amongst the people of the hills:

“This affective dimension is intricately interwoven into the texture of culture and language. The affective dimension is best captured in the literary mode. The construct of identity through literature has a past of its own. Every generation as it were, depicted the affectivity surrounding oneself and the collective self in poetic or prose articulations, in novels or in short stories, in dance, music and folk songs and these communicated to a distant land, people and time and sense of self identity…” (Thadathil 21)

The author does not complicate concepts or words; the objective transmission of knowledge and resourceful results contribute to the picture of what Darjeeling was, how it has progressed over the years, and what the current state of Darjeeling is. The author effectively expresses by drawing upon oral histories as well as written documentation, to provide newer insights into the realms of Darjeeling. Postcoloniality has isolated regional monotony in literature, and diasporic needs have given birth to newer settlements that new generations in Darjeeling are continuously attempting to uncover. In spite of that, the authenticity of the mother tongue by retaining the traditional norms, rituals, family practices, cultural phenomena, and literary outputs helped Darjeeling to grow in its own rights and measures. In this connection, one chapter of Democracy in Darjeeling definitely needs a special mention here.

Chapter 5, titled ‘Darjeeling Hill University: Emergence of a People’ is a study that takes into account the precise background idea of what a university is, what were the prerequisites to establish European model universities, and Darjeeling as an ideal place to set up a university (a onetime dream that materialised in 2022) as there is a presence of a native ‘polish’, ‘finesse’ and ‘wisdom’ in the hills, that has developed over time. The impact of the colonial legacy and the proximity to the British had expedited the process of developing this fine, refined sensibility among the people of Darjeeling and adjoining areas. The dissemination of knowledge in schools, colleges, and universities is different. Christianity was also a major force, rather advocate for the advancement of English education in Darjeeling. One critical element to consider is basic access to schools, colleges, and universities. With the passage of time, it is also about the utility and accessibility of education in terms of technology. Before establishing any educational institution, employees, buildings, funding, dormitories, libraries, labs, forms of communication and transportation, and other similar relevant aspects must be considered. The author writes:

“Establishment of a university in a certain place has a purpose. Once upon a time, probably, it was a top-down procedure. Somebody somewhere saw the need for a university at a certain place. For example, the first university college of India was opened in Calcutta because it was a felt need in London that it would be good for managing affairs in India.” (Thadathil 71)

It is true that the concept of vidya and vidya kshetra in Oriental terms has much to do with the overall cultural assimilation of several factors. A university is not just a building made of brick and mortar, but it is a constant effort to expand the horizons of practical knowledge. As the author writes very adroitly, there are several stakeholders in the smooth functioning of the process. If the government sanctions a certain amount for establishing the university, the work does not end there. Rather, it is about the educated parents, students, management, academics, and the culturally enriched groups, and individuals who must affirm ‘why’ they need a university in the first place. The ‘why’, ‘how’, and ‘when’ triumvirate should form the pivot of discussion in this connection. If there is unnecessary sloganeering and hooliganism and excess of political unrest in a university, that results in nothing but utter chaos and defamation for an academic system, and consequentially, instead of a sane representative of education, a Frankenstein is born whose actions are detrimental to any sort of academic or artistic accomplishment. Darjeeling has the complete set-up to kindle and inculcate a holistic goal among the students, helping them not just in class, but also in literary activities (setting up literary clubs), musical bonanzas, sports activities, and so on. This is a pluralistic approach, of course, retaining the individual essence of quality education in all its aspects.

American political scientist Theodore J. Lowi identifies the basic concept of pluralism in his discussion of the ‘Pluralism Matrix’ (‘Plural Forms of Pluralism’) as part of the edited volume Pluralism: Developments in the Theory and Practice of Democracy:

“Pluralism exists in the identities people develop out of the places, positions and cleavages they occupy. Pluralism is civil society wherever the separate identities are allowed to develop and express themselves.” (Eisfeld 25)

Pluralism indicates diversity, and it is evident in the identities of the people and includes the fundamental right both to agree and dissent. Chapter 6 of Democracy in Darjeeling is titled ‘Democratic Pluralism or Pluralistic Democracy: Colonial Legacies and Post-colonial Possibilities.’ It deals with a methodical approach and then a fundamental analysis of the multi-layered trajectory of Indian democracy, postcolonial identities, and the effect of pluralism. The post-independence scenario in the country was marked by a representation of the Bahujan and the Dalit parties, large-scale privatization, and liberalization of the economy and even the non-party groups occupying a place of prominence. The author diagnoses the plausible structures and implications of a pluralistic democracy, and how the preparatory ground for the amplification of the regional and national goals was made. The recognition of several languages, communities, and tribes in the hill areas also commingled with the recognition of their identities and through cultural patterns that were naturally practiced and that were not thrust by an external force. Along with that, the author also reflects upon the tectonic shifts that occurred in the Hindu and Christian beliefs of the ‘good life’:

“For the Christian, ‘good life’ is in the future, to be attained, worked for and striven after. For the Hindu, the good life is a pre-given, an ordained position in society, not to be challenged or trampled upon. Therefore, for one freedom consists in preserving the patrimony, tradition already given.” (Thadathil 100)

The next few chapters are about the process of democratization through civil society institutions in Darjeeling, history, culture, environment and development, a socio-religious description, and philosophical reading of Dhajia, the environment as a matrix for enabling cultural identity, the role of social sciences in the promotion of science, religion in Darjeeling, protest masks, religious pluralism, and movements. Each of these chapters highlight the ways in which democratization is a process-force in cementing the cultural and religious legacies of Darjeeling. There is no abstract meandering that the author does, nor does he raise blatant political questions or insinuating remarks that might kindle religious fury. The book is a collector’s item in its own swift flow and expressional luminosity. The author has woven a fine tapestry with facts, insights, and philosophical reflections, free from didactic jargon and obscure educational rendering. The condition of the tea-garden workers, plantations covering a large area of Darjeeling, religious practices, and socially-sanctioned goals are not historically mundane, as the author corroborates. This book itself is a process, a process that emanates from an in-depth study of Darjeeling as a democratic entity, and not just a geopolitical ‘space’ in the strictest sense of the term. The role of the missionaries in the past and present, combined with the infringement of modern ideas that affect the dreams and aspirations of the youth of Darjeeling are bound to give rise to both cohabitation and competition. In addition, when we study the religion and cultural paradigms in Darjeeling, we discover how the people’s history is inextricably linked with the same. Tanka B. Subba, who has also written the Foreword to the book, in his article ‘Do People Exist?: The Problems of Writing People’s History’ enumerates:

“If Darjeeling is conceived merely as a place, the answer is no, because people’s history is, according to Raphael Samuel, not about ‘places’, but about ‘faces’, or individuals and their lived experiences. But Darjeeling is not just a place, and a celebrated one at that, due to its world-famous tea and its place in world tourism, but also a place where more than one dozen ‘peoples’ have been living for centuries under the domination of the ruling classes in West Bengal.” (Subba 12)

It is true that the process of democratization does not happen overnight. In chapter 7 titled ‘Democratization process through civil society in Darjeeling district’, Thadathil traces the development of Darjeeling district passing through changing political conditions including the functions of the trade union in ensuring fair wage earning and rights of plantation workers. One of the most incisive remarks that the author makes in this chapter is how the percolation of democracy is necessary to ensure its reach down to the grassroot levels. Within the local population of a district–there are layers available downward to the block, panchayat and village–the concept and application of democracy varies from one region to another. The writer makes every possible effort to make the readers not oblivious of the sustained interest of the small target groups that might, in any way, harm the assumptions and proclamation of national integration. In hill democracies, the presence of minority groups and ethnic complications often plays a significant role in shaping political dynamics and governance. These regions are characterized by diverse populations with distinct linguistic, cultural, and sometimes shifting religious identities. As a result, the management of minority rights and ethnic tensions can be complex and challenging. Minority groups in hill democracies often demand equal representation, and protection of their cultural rights. Failure to address these concerns can lead to social unrest and instability. Ethnic complications can arise from historical conflicts, territorial disputes, or competition for resources, exacerbating the challenges faced by these regions. Political institutions in hill democracies must navigate these complexities by implementing policies that promote inclusivity, decentralization of power, and the recognition of cultural diversity. Devolution of authority to local administrative bodies and the creation of special provisions for minority rights, be it linguistic or religious, therein can help mitigate ethnic tensions. Additionally, fostering dialogue and reconciliation processes among different ethnic groups is crucial for achieving long-term stability and social cohesion in any democratic space. Ultimately, addressing minority issues and ethnic complexities is essential for the success of these unique democratic systems, to ensure that all citizens have a voice in the decision-making process and promoting harmony within the diversity of hill regions. As Thadathil probes deeper into the realms of cultural organizations and their contribution to the local democracy under scrutiny, he says:

“The cultural organizations that are mushrooming all over the region in the name of promoting one or the other social, religious, or cultural issue is equally to be noted. So too, sports clubs, music clubs, Independence Day celebrations, marking the birth and death centenaries of noted personalities (including Bhanu Jayanti) community halls construction, maintenance and promotional activities.” (Thadathil 115)

Hence, we are looking at the completion of a body politic. The body of an autonomous state and a democratic nation. Close, well-knit groups of men and women are taking recourse to healthy lifestyles, tourism activities, and reduction of social malaise to integrate extra efforts in the conservation of the democratic ideals in the hills. And the historical and cultural paradigmatic shifts are brought into a further academic and comparative loop when in chapter 8, the author studies the contrast between Kerala and Darjeeling in terms of history, culture, environment, and development. In Kerala, just like in Darjeeling, over the last few decades, the range of homogeneous, singular language-based communities have experienced a major alteration across layers. The areas have witnessed large-scale migration to several parts of the city, urbanization has resulted in new opportunities and more liberal ways of looking beyond the apparent veil of democracy. However, urbanization in both Darjeeling and Kerala also presents challenges, including overcrowding, increased demand for housing and services, and strain on resources. Effective urban planning and development are essential to address these issues, ensuring that cities can accommodate their expanding populations sustainably. Furthermore, urbanization and migration bring together diverse cultures and backgrounds, making cities hubs of cultural exchange and innovation, enriching societies, and economies. Further, the book depicts a discussion of the environment that plays an active role in the larger matrix to ensure cultural identity. Both the internal nature of man and the external nature, environment, flora, and fauna of Darjeeling redefine and authenticate the larger, more profound, and super-sanctified goals of becoming an ethical human being. The individual and collective consciousness of the people of Darjeeling resuscitated the primordial ideas of existence and belonging to a homeland. As George refers to the critic Ramachandra Guha’s opinion on environmentalism, he narrates:

“In talking of how environment nurtures culture and culture in turn shapes identity, one cannot but refer to the path breaking works of Ramachandra Guha, in his ecological history of India ([This Fissured Land: An Ecological History of India]) and the Global History of Environment ([Environmentalism: A Global History]).” (Thadathil 163)

And the following chapter discusses the role and function of social science in promoting this cultural notion of the homeland wherein the promotion of a scientific temperament is no less important. One particular cohesion in this text, however, is worth re-reading. Chapter 12 concentrates specifically on religion in Darjeeling, and in this chapter, the author has dexterously balanced the sacred and the secular space in Darjeeling. There was a prolonged period of gestation when the age-old religious practices remained obscure and for the most part, detached from the mainstream religious segments. Relics, cultures, the democratization of knowledge, and abstract and abrupt sanctification have their own curious way of cementing popular culture and relationship formation. Thadathil explicates the various religious outlooks that we find among the Rai Muddum, the Tamang, the Sunwars, Gurungs, Magars, and the Limbus that retain the unique identification parameters as well as the virile, staunch adherence to nature and supra-natural worshiping. Even the penultimate chapter and the last chapter unequivocally expand the scholarship around the issues of culture, identity, and the trajectory of interfaith dialogue. What else can be beneficial for fostering the quintessence of community growth and regional development? It is laudable how the writer has created an all-inclusive umbrella even of disparate social, religious, and cultural forces that are well-integrated as part of the national fulcrum.

Arguments and counterarguments keep on resurfacing, but Darjeeling remains a Leviathan in its own dynamism, penning down its own stories relentlessly, projecting a unique identity and not hegemonized, petrified, or desiccated by the spectre of foreign invasion or globalization. Perhaps, therein lies the success of any true democracy, and Thadathil has expounded upon this truth with extreme flair and diligence.

**

References: Arblaster, Anthony. Democracy. McGraw-Hill Education (UK), 2002. Eisfeld, Rainer. Pluralism: Developments in the Theory and Practice of Democracy. Verlag Barbara Budrich, 2006. Ray, Dinesh Chandra, and Srikanta Roy Chowdhury. Darjeeling: In Search of People’s History of the Hills. Taylor and Francis, 2022.

******

Sreetanwi Chakraborty is an Assistant Professor in Amity Institute of English Studies and Research, Amity University Kolkata. She is also the chief editor of a bilingual biannual journal Litinfinite, with multiple indexing of international repute and archived in 240 global libraries. Apart from her research papers published in Scopus, Web of Science and UGC Care journals, her works have also been published in Ekdin, Uttarer Saradin, Setumag, Dainik Gati, The Darjeeling Chronicle, Darjeeling Times, POL, The Dhaka Review, The Dhaka Tribune, Outlook India, The Times of India,The Daily Bhorer Alo (Bangladesh), Muse India, Kochi Post, Kavya Bharati, Asian Cha, Poetry Potion (SA), Poetry Conclave and many more. She has read her poems on invitation by the Sahitya Akademi, the WB Kabita Academy, Samyukta Poetry and acted as a poet and session moderator at the Chandrabhaga Poetry Festival. Her book The Sleeping Beauty Wakes Up: A Feminist Interpretation of Fairy Tales received the ‘Rising Star’ non-fiction award in New Town book fair in 2019. She has two sole poetry books and is an invited poet to 18 anthologies. Her recent work includes ‘Rhododendrons’, a novella, 'Of Dry Tongues and Brave Hearts' (Anthology, English, Red River Publication) and a translated short story in an anthology of Kazi Nazrul Islam's short stories, a project from Kazi Nazrul University (Orient Blackswan). One of her paintings has been selected by Sahitya Akademi as the cover design for Prachi journal in 2023.

Leave a Reply