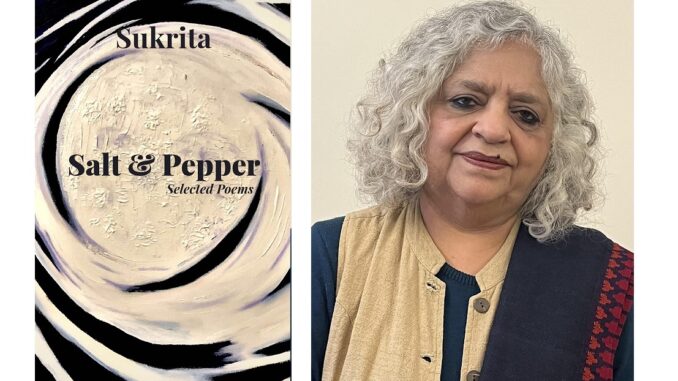

Salt & Pepper. Selected Poems. Sukrita. Paperwall Publishing. April 2023. 196 pages

T

he latest anthology of Sukrita’s poems Salt and Pepper traverses the poet’s momentous journey of nearly four decades. The poems bring us to a world not altogether unfamiliar— but a world imbued with a sensibility that is fine, complex and aesthetically profound at once—a world that kindles our hopes, fears, memories and beliefs and yet invites us to put on trial many a myth we have partly perpetuated. Simple, yet deeply philosophical, the poems have the power to resonate with readers everywhere. This inherent universality of Sukrita’s poetry gives it a timeless appeal.

Sukrita has divided the book into four sections. The poems in each section refer to the period mentioned within parentheses alongside the section’s title. The first section is entitled “Potter’s Soil” (1980-95), the second “On the Wheel” (1995-2010); the third section is called “Fire of Meaning” (2011-15) and the fourth “Across Lines…Across Time” (2016- ). Sukrita appears to have shuffled and reshuffled her creative pieces to choose the most appealing ones in this collection. In the foreword perfectly entitled “The Question of Homing”, the poet refers to the commotion memories spark off in our subconscious. Moving between vibrant places across time and continents, these memories eventually transform into poems. Since they are seated in the heart, they are marked by a certain subjectivity. However, suggests Sukrita, the process of selection has to have a certain detachment where the poet becomes a reader looking at her own creations dispassionately.

Eventually, the poet succeeds in effacing the personal and paints her canvas making largely objective choices.

By naming the first section, “Potter’s Soil”, perhaps Sukrita refers to the creative impulse ready to be harnessed. The second section “On the Wheel” conjures up the image of the potter’s wheel, as the ‘potter’s soil’ is now ready to be turned into objects d’art. What strikes one, though, is that the early poems look as meaningful as the later ones in terms of craft or thematic content. Sukrita herself also points out: “While some poems of the earlier times could well have been created now, some recent poems could have been written long ago (ix).” Perhaps, this quality makes Sukrita’s poetic oeuvre exceptional. She belongs to that league of artists whose work has that overarching serenity, which other poets attain after a considerable amount of time.

Most of the poems take us to the realm of profound depths of human psyche where the familiar but scarcely articulated state of being invariably finds an expression. In the poem “First Love”, taken from the second section of the book “On the Wheel”, the opening line grips our attention: “That which remains most is what leaves us” (59), occurring as a refrain in reader’s mind even while reading the poems that follow. One is overtaken by an urge to read and re-read this poem as one frantically searches for the essence of this line that perplexes and hits one hard at once. While what remains does not appear to linger on, it is there “to touch/to smell/or to taste…remaining in the privacy of silence uncomplaining” (59). While this poem was composed relatively early, it is comparable in depth to another poem entitled “Possessed”, taken from the third section “Fire of Meaning”. This poem refers to the absence of freedom of choice even as menace stares us in the face. Whether it is “a black well” or “stupendous waves of ocean” or “the open mouth of tiger”, one can do little: “I have no option/but/to take a step forward/when I hear the call…” (116). Equally deep and philosophical are the snippet poems appropriately entitled “Seedlings” in the first section, ‘Potter’s Soil’. As the poet herself acknowledges, “Like many others, the following little poem has been my companion vibrantly all through my poetic career” (x). This poem is in a class apart in depth and meaning: “When my shadow/ overtook me/ I knew/ I had crossed the sun” (4). Each of the snippets in “Seedlings” has a rare poignancy: “It was a fatal accident/my mind encountered yours/some moments breathed their last…” (3).

Poem after poem one is ensnared by the effortlessness with which the poet paints pictures that come alive with colours and images—precise and clear, never muddled or hazy: “I paint you/ Blue red or white/ Green brown or black/ A fresh shade for a fresh day” (6). And again in “Sunrise”, one comes across a panorama of colours: “A rich black mingle/with deep blue/and build a barrier/between the earth and the sky…” and finally “Numberless arms embrace the/falling colours” (9). In another poem, colours occur as metaphors for love and hate: “Love/is an osmosis/of all whites/and/all blacks/Hate is when/blacks are divorced/from/whites” (37).

The poems, many of them, in this section are quintessentially imagistic. The images are sharp and precise. There is brevity of expression. Stylistically too, they follow the free verse pattern, defying the rules of punctuation—no full stops, commas, exclamation signs et al. The poems create their own rhythms, breaking the sentences at unusual places to give emphasis to certain images: “The passage/to my mind/is/dark and long…” (19). In “At Single Point”, every line is divided after a word or two: “Through/the/ sea/of/blue/I/spin//to a/stillness/in the/centre/of/the/sky” (30).

Sukrita’s poetry is unmistakably steeped in the spirit of animism. Perhaps, this could well be the result of “calling from Africa”, as she puts it. Her love and veneration for the inanimate mountains and the living beings alike bears out the poet’s powerful connect with nature. Perceptive, sensitive and appealing, these images stay with the readers facilitating their own coordination with nature. Love for trees—the oaks, chinars, cypresses and banyans—assumes a form of quiet reverence. And this has stayed with Sukrita across time. All the four sections are splendidly evocative of the strong love and veneration for trees. In the first section, the poem “Vegetative Loneliness” opens with the line “Trees are like yogis” (7), referring to the stoicism trees exemplify. In the same section, another poem “The Oaks of Summerhill”, refers to the “[a]ncient oaks…witnesses of/ unwritten history…spreading over/mute mountains/Oaks and sages/share their wisdom….” (36). In the second section, that is, “On the Wheel”, the old oak is referred to as grandfather in the poem “The Burden of History”: “the ants crawl “…on/the wrinkles/of/grandfather oak….” (47). In “Talking Aloud”, the oak becomes “the great Grandfather Oak/that great Sufi, the witness/with long thick hair…” (77). The trees seem to offer boundless solace: “…observing you, My Chinar/year upon year/Your leafless arms/stretching out to me/ through biting wafts/of mountain breeze” (77).

In the last section “Across Lines…Across Time”, in the poem “A Dastaan Never Told: Dedicated to the memory of Baji”, the metaphor of the large banyan tree is reminiscent of the magnanimity of “our Baji”: “A grandiose banyan tree with roots deep in history/Friends and foes soaked in the foliage of her love, / That was our Baji….”(167). The tree metaphor in this poem transcends itself as the still waters around “Majestic and noble” Baji turn into flash floods when “…a thousand thousand watts-bulb lit up/Igniting the riots of Partition, the flames still flapping/seventy years later…” (167). Partition as a theme is close to Sukrita’s heart but this poem bares the “bloody wounds of 1947” with an intensity that is unmatched: “The train filled with corpses coach after coach/ With heavy steps she boarded, on top of the carcass…” (198). Sukrita’s poetry sometimes seems to celebrate pure art but her deep social consciousness and her pain as she sees the very core of humanity falling apart is a haunting quality of her poetic oeuvre—expressed ever so candidly.

Reading Salt and Pepper, one realizes that Sukrita’s poetry defies chronological progression in the ordinary sense of the term. One set of poems written within a specific time span melt into another set of poems composed at another time. This is beautifully illustrated through poems that are dedicated to individuals or allude to them. One just cannot flip through the pages and be captivated by the surface charm of Sukrita’s poetry. She invites one to delve deep into history, cinema, literature and people. “In Continuum” subtitled “For Yunus Jaffrey”, “Sophie’s Choice”, “One and Only”, “When the Snakes Came for Shelter”, subtitled “Dedicated to Freedom Nyamubaya”, “Colour that Bleeds” subtitled “For Toni Morrison” and “Arrival at Paris” are powerful statements about people, who were heroes in their own right. Sukrita’s choices define the poet herself and make a statement. Traversing through her oeuvre, one is acquainted with the vastness of her journey and the depth of her persona.

Words and silence are eloquent metaphors in Sukrita’s poems; many a time they are stripped of their familiarity and dazzle as symbols loaded with deeper meaning. The infinite power of words is beautifully spelt out in the poem entitled “The Art of Wearing Bangles”: “The blank page wears words/With the fondness and patience/ Of girls wearing glass bangles… (94). The poem “Being” exquisitely defines the power of silence: “The river of/ silence/ flows gently/ growing stronger/with time” (49). And in “Breaking Silence”, the strength accumulated during silence finds a perfect expression: “Words fall/From her mouth/As rain/On deserts…Words dropping/As stones” (52). And again, in the same poem: “Words as frozen ice/ Stuck in the /Throats/Of lovers…Melting in thought…Words collecting in/unuttered sentences (52). In “Talking Aloud”, “the white silence of the winters” (77) is an image that creates an indelible impression in the readers’ mind, with the rainbow emerging in the backdrop, as the poet sings along with her Chinar. Words per se are dead until someone breathes life into them. This idea ‘comes home’, to use Sukrita’s favourite phrase, in “Words Gallop Home”: “Come breathe life into/Words/ Words are stones/when in exile/ Those not owned by poets/remain lifeless and limp in isolation/not able to change sides/They are fossilized” (95). Sukrita’s poetry is a telling example of how words and silence become vibrant metaphors complementing each other.

“In Search of the Snow Leopard” is a deeply ironical poem. The prey of snow leopard must be followed to find the leopard. The distinction between the hunter and the hunted dissolves as the images of the foot prints of the prey and pug marks of the snow leopard coalesce. One wonders who is “…Fleeing in terror”, the leopard or its prey as the poet refers to the “Hatted and booted men/ In search of Gyamo the snow leopard” (158). The images of “Foot prints and pug marks” (158) are used as anaphora at the beginning of stanza after stanza in Part 2 of the poem to convey the bizarre unison of the hunter and the hunted, who are liberated as their pug marks and foot prints disappear: “No foot prints or pug marks/ Are proclamations of / Freedom…” (158). This image is crystallized further in the last poem, “Vanishing Words” as the poet voices her perplexity: “Why would the tiger of silence/not leave any pug marks/behind in the forest of words?” (179). Sukrita’s poetry and the motif of silence are inextricably intertwined. “Vanishing Words” is an iconic poem of Sukrita—subtle, powerful and compelling. It celebrates words that emanate from cacophony and yet embrace silence as they “cancel all noise in themselves…” (179). The poem epitomizes that colourless space, perhaps silence, into which words vanish “past sound beyond meaning” like pug marks of the tiger of silence.

In many poems, Sukrita touches upon subjects that jolt us into an awareness of sordid reality we refuse to acknowledge even to ourselves. “Tsunami Snapshots”, “We, the Homeless” and “Dialogues with Ganga” are poems which disturb our sense’s repose. The last of these is epic in proportion as the poet invokes the river, that rules our consciousness, to heal our battered and bruised world—be it the “blasting and exploding” Himalayas or the “battered and chopped people of different Gods” or “the deadly virus” that threatened to consume humanity. An extremely powerful poem, it speaks volumes about the poet’s empathy with the suffering humanity during the Pandemic and the war within that rages and divides.

The multihued and vast canvas of Salt and Pepper holds out endless possibilities of looking at the familiar and the unfamiliar in myriad ways. The anthology bears testimony to the fact that poetry has the power to create bridges where none exist. While art can exist for art’s sake, it also has the potential to transcend barriers of all kinds vis-à-vis its form and content. The French poet Stéphane Mallarmé once observed: “It is the job of poetry to clean up our word-clogged reality by creating silences around things”.

Perhaps, Sukrita’s poetry lives up to that ideal perfectly—creating images where words vanish and “the tiger of silence” leaves invisible pug marks.

******

Girija Sharma retired from Himachal Pradesh University as Professor of English in June 2018. Besides other academic and administrative positions. She also worked as Dean (Languages) and finally as the Dean of Studies till her superannuation. In 2022, her translated pieces appeared in two volumes of the Writer in Context Series entitled Krishna Sobti: A Counter Archive and Joginder Paul: A Writerly Writer, both published by Routledge. She also translated a volume entitled Taj Bibi written by Rajendra Ranjan Chaturvedi for the series Sanjhi Sanskriti ke Nirmata brought out by Centre for Cultural Resources and Training (CCRT) in 2022.Her translated pieces were also included in Joginder Paul: A Reader (2023) published by Sahitya Academy. Her research papers and book reviews have been published in national and international journals and anthologies. Her areas of interest include Postcolonial and Commonwealth literatures, Regional Indian literatures, New Literatures and Modern and Renaissance Drama. She has co-edited three academic volumes, Echoes Across Cultures (2004), Ripples on the Sands of Time (2013) and Reflections from the East and West (2012) published by Oxford University Press and Orient Blackswan respectively. She was also the Editor of Himachal University newsletter Himshikhar.

Leave a Reply