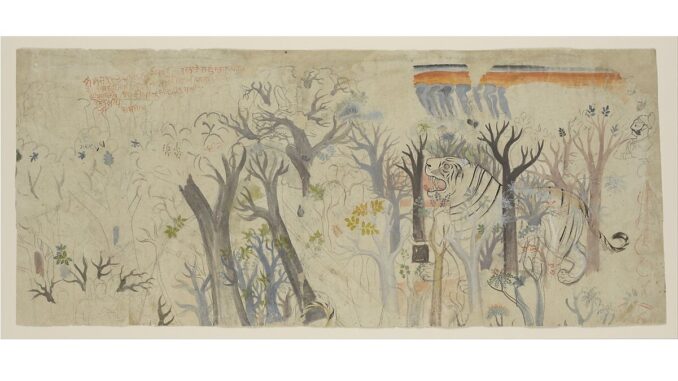

Tiger hunt by Sheikh Taju.1780 Courtesy: The Met

I

t was at the weekly market he heard that the taxidermist in Ajmer was looking for a tiger skin. Fifty thousand rupees! There was a challenge of bagging the animal, but it was the amount that had re-ignited in him the desire to hunt.

Bashir looked under the wooden family bed to see if the double barrel hunting rifle left to him by his father was still there. His father, until his last days, would proudly proclaim, “We’re Khandani shikaris. Our ancestors served as hunters and game keepers in the courts of Mogul and Rajput kings.” After tiger and cheetah skin trading had been declared illegal, his father would turn to the raggedy mattress. From under it, he would take, one by one, the skins he had saved from the past hunts, and sell them. He had heard his father shouting angrily, “With these government sanctuaries, what’re we to do – become Mahabots and Chara-cutters?” Many of his relations now worked as elephant drivers, showing foreign tourists nearby protected woodlands.

The dusty Beawar-Tatgarh road — familiar to him since childhood, he could walk the thirty-mile stretch blind-folded. The first twenty-miles of paved trunk road ran through part desert part barren land, it ended near the Tatgarh Lake, then five miles of single lane dirt road in the rocky hills; and finally the sloping serpentine pathway winding through a scrubby bushy landscape into a valley with full grown forest, dotted by patches of dried shrubbery.

By noon, Bashir had reached the Tatgarh circuit house, the government rest house where the district officials and timber contractors stayed during the logging season. In old days before the hunting became unlawful, the rest house throughout the year was full of hunting parties. The circuit house stood majestically on the hill above the lake. He remembered visiting it first with his father on a hunting expedition. He had been struck by its spacious rooms, the high ceilings, and huge central staircase. While the guests took the break inside, he would sit outside on the back porch with his father and the Khansama, the cook, to work on cleaning the game – barasingha, deer, rabbit, quail – stripping the carcasses of the animals, removing the pellets from the flesh, separating the edible meat from the innards.

When it was a big game, all three would tackle the animal with thin razor blades, making sure the skin stripped from the dead animal was not damaged or severed from the head. Because of his small fingers and supple wrist, his father would give him the meticulous task of peeling off the skin. The stringy pink flesh and the pungent smell of the animal permeated. He would carefully roll the skin and soak it in the canister of spirit. On reaching home, he would stretch the skin on the old wooden frame till it dried. Father would then, on the morning commuter train, take it to the skin dealer in Ajmer.

The Khansama, a thin wiry old man with a wrinkled gaunt face and a full head of white hair served both as guard and a cook at the circuit house. He recognized Bashir as he passed through the wooden gate on his handlebar bicycle. Khansama’s sharp eyes could not help noticing the grey blanket bundled along the crossbar between the seat and the handle of the cycle. Alluding to the gun wrapped in the bundle, Khansama remarked,

“Ready for the hunt again, Bashir?”

He nodded.

“That gun is like a charas to you. You’ll never give it up. A shikari, like your Abba.”

He felt uneasy at that comparison. His father was a professional. Him? He had been a labourer, a watchman, a trucker, a mahabot… but there was a lot missing to claim the same title as his father. Hunting was no longer an occupation to take pride in. To his children, a hunter and a mutton shop butcher were the same. He had heard that, in some towns, if the constabulary found out that you were a shikari, they would raid the house to confiscate the guns you kept without a license. He detested the word “poacher”, a shikari was not a thief, he was born to hunt. Soon after his father’s death, he had taken the rifle off the wall in the front room, and hid it in the large wooden trunk under the bed.

He rarely hunted these days; mostly, it was small game, mainly fowl. And it was only when he was in dire straits, or in between jobs to earn some extra cash. Yet, there was also the irresistible desire, as Khansama had said, to use the gun. A man had to stand up sometimes to prove to himself that he was, if not better, at least as good as his father. He had to find out whether he was made of the same stuff, belonging to the same lineage of hunters as Abba.

During his youth, he recalled, at the lake, rowing past the black buffaloes cooling themselves in the muddy waters, father would know the exact location of the fowl – the flight paths of herons, cranes, geese and ducks. Assisting his father, he would point to the clear blue sky, “Abba, look up there…” And the bullet would explode with a thundering sound in the sky bringing down half a dozen birds in one shot.

“Bashir, God is bountiful!” Father would shout.

For hunting expeditions, his father was in unending demand. Invitations to work would come from Ajmer, Jaipur, and Delhi to be an official guide, a tracker, or a hunter…Depending upon the party, his father would set fees in kind, or money.

While negotiating the price, his father would tell the middleman, “Listen Miyan, I have served the best in the region. All British Angrez commissioners who ever came to Tatgarh circuit house sought my services. It doesn’t matter whether the hunt is in the marsh or the jungle, my price is always reasonable.” The jeeps full of mostly men in their khaki hats and safari suits with their rifles would stop by their home in the early hours of the morning. On some hunting trips, Abba would take him along as his helper… Yes, along the same route, the Beawar-Tatgarh road.

Bashir stayed at the circuit house with the Khansama for an hour before starting on the second leg of the journey on the bicycle. The old man inquired about his wife and children, and cooked fresh curried vegetable bhaji with the roti for him. Offering him the glass of tea, he told Bashir to save the meal he had brought with him for the night. He saw the old man’s dark eyes probing him, “Why’re you going there? There’s nothing left.”

Bashir forced a smile. The game had been hunted to the edge of extinction. He knew that. But the call of the forest was strong.

The Khansama laughed, “Bring me a tittar (partridge) on your way back. My mouth still waters for the bird.”

Taking leave of the Khansama, in the scorching mid-day sun, Bashir got on the rusty bicycle, and slowly pedaled on the dirt road towards the rocky hills. The bundle was tightly wrapped around the crossbar with jute strings. He felt the package to ensure that the rifle was intact.

**

With the evening drawing close, the shadow of the rock on the west side was growing longer. He wanted to arrive before dark so that he would be on equal grounds with the game he sought, cognizant of the terrain and the possible movements of his adversary. He had been coming to the jungles of Tatgarh for over three decades. Within a few hours of his descent into the canyon, he surveyed the scene from one side of the rock to its other end. The game lived in a couple of caverns, in small notches on the face of the rock, maybe it was resting.

His first few trips to the forest with his father were an adventure. He was awed by its grand setting. The mighty pink granite rocks on top and the canyon below were camouflaged by a green canopy of saal trees and a winding stream running through it. Those who had been to the canyon spoke not of its natural bounty, but of its dangerous wildlife. As he grew older, he realized that the dangerous side of the canyon had been exaggerated by shrewd elders who did not want to share its hidden riches with outsiders. The forest was habitat to a variety of colourful birds, peacocks, black monkeys…the pink langoors who swung freely from one branch of the tree to the other. On the ground, there were wild boar, deer, antelopes, foxes, jackals, and hyenas – the witchlike laughter of a hyena made his hair stand on his arms.

He remembered during his childhood, hunting was limited to the edges of the canyon. At the bottom of the ravine, there would be a sign nailed to trees where with black paint someone in English had scribbled: ‘Hunting Not Permitted’. Abba, from the front seat of the jeep would warn his clients.

“Read the sign carefully please! No one is to shoot until we are out of this stretch.”

He had learned from his father respect for the big game. Lions, tigers, wild boars – they only killed the other animals for their self-preservation. There would be all sorts of questions, raised in whispers by men in the party, asking his father the reason for the restriction. Father would point to a small white cottage with a sloped roof made of corrugated asbestos sheets in the ravine. The not to shoot orders came from the man who lived there. In such a thick jungle, to see someone living all by himself, his sense of awe had heightened.

Bashir stopped by the stream to check for possible tracks in the coarse damp sand. Some pug marks of jackals and hyenas, and tiny clump paws of deer and chital. The sound of the water flowing over the rocks and boulders wove into the flutter of crows and mynahs which flit-flashed their way in and out of the thick leaves. The lusciousness of the forest gallery was, however, deceptive, as further beneath that thick foliage laid the stumps which, in recent years, had been either logged or blighted by disease.

Bashir chose the strong old bargad tree for the camp. He laid the bicycle by its trunk, removed the bag from the carrier, and took out the food, flashlight and ammunition. Then he untied the blanket in which the rifle was wrapped. He decided to spend the night at the second fork of the tree which was high enough as a lookout and for safety. The view of the rock and the stream in the dusk, from the top was magnificent. Gradually, the chirping of birds died down.

As the darkness set, the stars gradually appeared in the clear sky. With an incessant chime of frogs and crickets in the background, the whiff of fresh moisture from the earth and the lush vegetation overcame him. Along the stream, with his father, he had stalked all sorts of animals, from a nilgai, swamp deer to a tiger. Both Abba and he had crawled on their stomachs in the undergrowth, sat on the tree, or sometimes hid behind the stone reef in search of the game. He wondered what happened to all those animals. Were they never to return?

There were however few things that stayed on, Bashir mused. They momentarily disappeared to reappear next day, next season, next year – the vegetation on the rock, the little rippling falls originating somewhere from the middle of the mountain transforming into a rivulet meandering through the canyon… the sun, the moon, and the stars… these served as witnesses to good and bad in God’s Kingdom. Peering into the darkness, he wanted to believe that there was game in the thicket below.

His first tiger sighting along the bumpy uneven dirt road from the front of the jeep, his father sitting next to the driver was speaking to the members of his hunting party.

“Do you smell anything? It’s the meat odor.”

Then suddenly he directed everyone to look upward to the right.

“Look carefully, do you see the cavern. It is a tiger’s cavern – the cave of Swami’s tiger. The tiger is having its meal. No hunter can touch the animal there.”

Later in the day his father brought him closer to the site. He remembered his father nonchalantly telling him, “Bashir, we must show you a real tiger today.”

As they trod softly through the tall dry grass, his heart pounded. Abba nudged him to look into the open. An enormous amber cat with black stripes, pudgy paws, proudly standing in the middle of the dirt road staring in their direction. He remembered, vividly, the wide forehead, the large nose and sharp bushy whiskers. Those two burning yellow orbs incessantly looked into the bushes where he and his father were hiding. Father had pointed out, “you see those three stripes on the tiger’s forehead?” Unlike the other stripes, the dust grey stripes on the animal’s forehead were broken, forming a bolt like a frown in the middle, reminded him of the ash smeared foreheads of holy Sadhus.

“This is why he is called Swami’s tiger.” He could feel his father’s protective hand on his shoulder, “He won’t touch us. He’s the king – Raja. ”

As the tiger opened its jaws to growl, he saw for the first time the animal’s dagger-like four sharp teeth on both sides of the jaw, running a chill down young Bashir’s spine. Father was attentively calm.

“Don’t be afraid. Even Raja has its rules.”

Bashir smiled, though with some trepidation. Abba told him that the canine teeth were used by the animal for piercing and gripping its prey. The tiger growled in their direction, as if fully aware of their presence, and then sauntered away.

On their way home in the evening, as the jeep passed by the cave again, he felt the tiger would leap out of that gaping hole in the rock. Bashir had not known then that same consummate nervousness in his stomach would repeatedly draw him to Tatgarh. The forest had been kind to him. He and Abba over the years, with various hunting parties, had bagged all sorts of game. Now with Abba gone, the forest stirred up memories of the past. Abba’s spirit was still hovering in those environs seeking to protect him. He had a feeling that once he stopped coming to Tatgarh, the link with his father would cease.

The knowledge of the jungle and the hunting had got Bashir the work at the loggers’ camp with a Sindhi timber contractor. Whenever the owner was at the site, he would ask Bashir to stay near him constantly. “Lalwani sahib, there is nothing to fear.” Bashir would explain, “Lions and tigers are kings of the forest, they have their prey in the animal kingdom, they are not interested in us.” The boss man putting on a tone of bravado would say, “I know that. But with my family and business, I cannot take any risk. That’s why we have you hired as bodyguard.” Trying to hide his smile, Bashir would reply, “Nothing to worry, sahib. I am always here.”

Whenever Bashir would make a kill of a deer or a boar, the camp cook would prepare a special meal for those overnight at the camp. Like his father, he would keep the skin and the antlers for trading in the bazaar. Or, if the kill was a rare wild animal, he would sell it to the taxidermist in Ajmer. The contractor was so impressed with his watchman job that he had offered to take him to the new logging site in the Northern Provinces.

Bashir spread the blanket on the bark. He knew it was going to be a long night. With a gentle breeze, in the darkness he could hear the rustle of leaves. He wondered if what Khansama had said was true that there were no more tigers left. What if the last remaining tiger, the Swami‘s tiger had also vanished like the holy man? Or, what if someone else had already hunted it down? Bashir had a hunch that Raja was still around. Over the years, he had sighted the animal in his cavern, at the stream, and even confronted him; but the tiger, after staring at him, would walk away in the opposite direction.

The big game was gone. Perhaps, with this hunt, there would be nothing left for him to come back. His determination to be awake was starting to falter. Having bicycled the whole day, tiredness was overpowering. His eyelids began to droop. Slowly, his train of thoughts turned into shapes and patterns familiar yet grossly exaggerated:

… Bashir is sitting on a swing tied by two thick ropes to the highest branch of the Bargad tree. He is enjoying the gentle back and forth sway of the swing until he is lulled into a slumber. He is awakened by the pace of the swing being pushed by a mysterious force on the top of the ravine. In one sway, the swing carries Bashir from one end of the forest to the other. He is enjoying the back and forth sway. The eye of a soaring eagle. Such a grand view of the luscious landscape. The green jungle with a shiny silvery stream twisting through it. The singing herons flying over the forest canopy. The herds of wild boars and antelope roaming about in the tall dry grass. The sambar and chital deer gathered by the stream grazing on waterweeds. The tiger with their cubs taking rest at the mouth of the cavern… Holding tightly on the rope, Bashir looks up. To his amazement the rope extends into the clear blue sky. He is unable to see the end of the rope. The sun’s brightness dazzles his eyes. Unable to continue looking upward, he turns his gaze down – suddenly, the lush vegetation of the valley has disappeared. It is replaced by smoldering trees engulfed in a fog-like smoke. No birds, no animals, no greenery. Only a valley covered with black dead stumps like the gravestones in an endless cemetery and a lone tiger running across that desolate space. The swing starts spinning in a circle first slowly, then rapidly like a merry-go-round. The swirling rotation makes Bashir queasy. He clutches on the rope, but his hold begins to slip, he feels as if he is about to be hurled into the air. The swing, the sky, the forest – all of sudden everything vanishes. Instead there is a round eye of a chameleon with its robotic movements staring in his face. The chameleon’s granular coarse skin changes its colours – yellow, black, green, red, blue, grey, orange, yellow – the lizard with its multi-colour veils sticks the fleshy tongue out at him. There is something eerie and at the same time familiar about the face. He realizes that it is his face. A sinister small chameleon face mocking him. Afraid, he cries out: “Abba!’’

Startled, Bashir woke up. The loud screeching sounds at the foot of the tree had stirred him. He could see two glowing orbs on the ground staring in his direction. It could have been anything from a jackal to a black bear. To frighten the beast, he stood up at the fork of the tree and pulled down his pants, aiming to urinate at from where the noise had come. The glowing orbs hastily disappeared into the darkness. He made sure not to doze off again.

Near the edge of the rock where once the hut and the water tank used to be, he could see in the darkness the white speck of rubble. The sound of the spring continued. Even though people had continued to spot the tiger long after Swami had disappeared, no one dared to hunt the animal. There were many stories about the tiger being the holy mount and protector of the Hindu goddess Durga.

The first time he saw Swami in person, it was with Abba. It was a late afternoon. He was struck by Swami’s friendly yet searching dark eyes. It seemed the holy man had just stepped out of the nearby spring water tank in the jungle. Wearing an ochre coloured long shirt to his feet, his shoulder long black hair was wet and stringy, The man’s beard dripped on to his bare chest. Covered by a cotton shawl which had religious symbols printed on its border, Swami rose from the bamboo cane chair near the tank to greet Abba.

“It’s you shikari!”

He was surprised that Swami knew his father as a hunter.

“Look, who have you brought this time?”

Father knew he was not referring to the accompanying hunting party but to him.

“Your son, shikari?

“Yes Maharaj.”

“Good, you brought him. He too should partake in God’s mystery. Come boy, what’s your name?”

“Bashir Khan.“

“Bashir Khan.” Swami repeated the name. “Bashir, the brave. You want to be a hunter like your father?”

“I don’t know sir.” He had replied meekly.

“Right. Who knows?”

He had innocently asked the holy man. “Sir, living here all by yourself, are you not afraid of being eaten by lions and tigers?

Swami had laughed.

“Animals can easily smell both violence and fear. But when they become friendly, they can also be protective and help humans. They only kill humans when attacked.” While Bashir and his father sat down on the ground, Swami sat back in the cane chair, ”Let me tell you a story you would like it.”

“When I came to this forest a long time ago, I had been walking for the whole day in search of a secluded place to do my meditation. It was late in the evening I decided to take a nap in a cave nearby. Spreading my blanket on the damp floor, I closed my eyes. No sooner I did that, I was awakened by two little tiger cubs pouncing on me. “

“Yes, that’s true.” Swami continued. “The little cubs, hardly 10 to 15 days old, they were like kittens all over me. The two might have thought that I was their mother. I think they were hungry looking for their mother’s milk. I lay there petting them. This went on for a few minutes. As I sat up, I saw their mother standing at the entrance to the cave.”

Bashir was spellbound listening to every word the holy man was uttering. Swami continued:

“First I feared that the tiger would rush in and attack me, but then a strong feeling came from within: I thought, I have no intention to hurt these cubs. If the tiger leaves the entrance of the cave I will go out. As I picked up my blanket to leave, the mother tiger backed from the entrance. When I had gone about fifteen yards from the entrance, the mother tiger calmly went in to join her babies.”

There was a benign smile on Swami’s face. “Have you ever heard of any Sadhu or Swami ever being attacked by a wild animal? Instinct is a great power if properly used, it can save us from many calamities. Humans are often not able to hold on to that and lose the game.” The saffron clad man was giggling. Then changing the subject, the holy man looked directly at him, “No more fear now?”

He nodded.

“That’s good. You had to be fearless in life. Go, take a quick bath in the tank. You will enjoy the water. Then I’ll give you some sweets to take home.”

Taking off his clothes by the tank, Bashir recalled having jumped into the water with a continuous flow from the nearby rivulet. Having the whole tank to himself with fresh cool water surging through it – was one of the unforgettable experiences in the open he would later recall. Through splashes of water, he could hear his father asking questions from the holy man,

“So Maharaj, what a Shikari like me to do then?”

“We all have to do our duty, you were born to a Shikari and you have to do your duty to fulfill your obligations – to take care your of your family – your parents, your wife and children. That comes first.”

Bashir never forgot that enchanting meeting with the holy man of the Tatgarh forest.

Once as they were leaving the Swami’s sanctuary, at the edge of the premises one of the men from his father’s hunting party, on seeing a cluster of partridges, could not resist pulling the trigger. The canyon had echoed with the gun shot. His father had jumped and snatched the gun from the man. Bashir had never seen his father angry that way at the city folks.

On one of his later trips to Tatgarh, he recalled his father had stopped by Swami’s hut. There were rumors that government surveyors were mapping the area to prospect minerals in the region. His father was concerned. He was telling the sage about receding forest land and his inability to make ends meet through hunting. Swami gently laughed: “The problem is that there is no end to man’s greed.”

It was around the time when loggers were moving into the forest that stories of Swami’s disappearance started to spread. At first, it was thought that he had left on pilgrimage, visiting the holy places in Pushkar. But with no sightings of him for a long time, other stories about Swami began to emerge. One tale being that the holy man had been eaten up by a tiger. They spoke about finding blood at the edges of the water tank. There were others who thought that he was in fact a bandit who had been hiding in the forest to escape from police and since police had come to know of his whereabouts, he was on the run again. That was a long time ago. Bashir had never been sure of the fact and fancy in these tales. As he grew up, he heard that the real story was that a logger who wanted an arbitrarily restricted domain for logging and mining in the forest, had the holy man killed.

**

It was dawn at last. The sky slowly changed from blue to light grey. A thin mist filtered through the galleries of tree. The forest was suddenly alive with the chirrup of birds, about to take off on their daily course. Even the langoor monkeys were active again, swinging from one tree to another. Bashir came down the tree to look at his bicycle. It had not been much damaged, except a few broken spokes. The animal, suspecting a trap had panicked last night. The visitor must not have been heavy, otherwise, the bicycle would have been trampled. There were claw marks quite high on the bark, long deep scratches. But he couldn’t determine whether they were recent. He stood the bicycle again against the tree.

He had a bite to eat and walked to the stream for a wash. The dawn melded into the sunrise with a fresh pink hue in the sky. The sparkle of the running water in the stream blinded him for a moment. A lot of wildlife traffic seemed to have passed at the waterhole throughout the night. Bashir’s nostrils picked up the acrid whiff he had scented yesterday for a few seconds. This time it was very distinct, the smell of the tiger’s dung. These must be fresh droppings. He could sense old cat’s presence around. Among the tracks on the wet sand, were the two pairs of four deep evenly spaced pugmarks with trapezoidal footpads. The discovery brought a smile of satisfaction to his face. His instinct to stalk Tatgarh forest had proven right.

He was in no hurry. The day had just begun. He knew sometime during the day there would be a direct confrontation with the animal. Stealth was the key to the hunter’s success. Unlike city hunters who used telescopic rifles, he sought challenge face to face. Both the hunter and the hunted were then on equal ground, only the end would reveal the real predator. He moved back to the tree by his bicycle. The rifle and the rounds of ammunition were intact. He rolled his trousers up to the knees. Wanting to be bare-footed to track the animal, he took off his shoes and put them in his jhola bag.

With the late morning sun hitting Bashir in his eyes, he was getting restless for the tiger. His prey must be playing hide – and- seek. The pugmarks on the dirt pathway had suddenly vanished. Bashir again cautiously moved through tall grass, dry bush…followed the jungle sounds, the alarm calls of the sambar and cheetal…but they all turned out to be false. He could sense a tension creeping inside him, making him feel alert and vulnerable at once. This was no time to be swept away by weakness. He wanted to remain watchful, to be alert and more clever than his prey.

It had gone quiet. Only the langoor monkeys were barking from the tree canopy. He did not know which way to look. His hands stiffened, his gun turning horizontal in quest of the target. There was a sudden thud. The bicycle crashed to the ground. As he looked towards the tree, he could not see anything. Yet he felt he had seen a flash of ocher and black moving behind the shrubs.

Bashir followed the movement into the dry thicket, this time determined he would not let it go. There was an irritable growl. Startled, Bashir found himself facing the prey. Instead of hiding in the grass, the tiger had moved into the open, wanting to take him on. It was the same tiger. The three faded ash grey stripes on the forehead, large, round, dark irises floating in flaming yellow orbs, arrogantly challenging the hunter. Throughout the day Bashir had been wondering was it right to have come to Tatgarh. Despite the possibility of hefty return from the sale of tiger skin, shooting Raja, the last of the big cats had somehow seemed wrong, it saddened him. He remembered Swami’s refrain of instinct that Abba used to remind him of — your inner voice would tell you the right move to make. Bashir raised the rifle, aiming to shoot. In the sight, he could see the magnificent animal. Suddenly he noticed the four sharp canine teeth from the front of tiger’s jaw were missing. This could have been due to its old age or a disease. The tiger continued to stand its ground, staring at him with its big fierce eyes, daring him to shoot. Bashir knew the animal would no longer be able to kill or drag its prey. Deep within there was something unsettling happening to him, a frustrating anger, about the iniquitous situation between him and Raja. It continued to prevent him from charging the rifle. The tiger slowly turned around, and disappeared into the bush. Bashir’s grip on the rifle had become unsteady, his shaky sweaty hands were unable to hold the barrel of the gun straight. The will to chase the old tiger had dissipated. He knew he would not be returning to Tatgarh.

*******

Balwant (Bill) Bhaneja was born in Lahore and left India in 1965 for Canada. He has written widely on politics, science and arts. His recent books include: “Peace Portraits: Pathways to Nonkilling” (2022), Creighton University and Center for Global Nonkilling, USA; “Troubled Pilgrimage: Passage to Pakistan” (2013), Mawenzi/TSAR, Toronto; a collaboration with Indian playwright Vijay Tendulkar, entitled: “Two Plays: The Cyclist and His Fifth Woman” (2006), Oxford University Press ,India; “Quest for Gandhi: A Nonkilling Journey” (2010), Center for Global Nonkilling, Hawaii, USA. As a playwright, his works have been produced by BBC World Service (English adaptations of The Cyclist, Gandhi versus Gandhi), Ottawa’s Odyssey Theatre (Fabrizio’s Return), and Maya Theatre (The Cyclist), Harbourfront, Toronto. From 2012 to 2022, he was coordinating editor for the peace and arts Nonkilling Arts Research Committee (NKARC) NewsLetter, Hawaii, USA. His short fiction has been published in English and Hindi including the cutting-edge webzine The Beacon. A former Canadian Diplomat with postings in London, Bonn and Berlin, he holds a PhD from University of Manchester, U.K.

Lush, leafy, verdant — what a refreshing work of fiction! My congratulations, Bhaneja Sahib.

Shukriya

Few write as well as Bill, on such a wide variety of subjects. His output is prodigious and there is always something to learn in his writings. Already, I am looking forward to see what will come next from this talented writer!

That’s so kind of you Ian.

A wonderful story Balwant, full of images, memory and family influences. Enjoyed it a lot

Many thanks

Thanks, Bill, for a vivid and captivating entry into Bashir’s world of traditional hunting through colorful jungle memories as well as his bleaker current reality and an irresistible pursuit of the ultimate game that ends in a surprising and nonkilling final encounter with the Raja where instinct wins.

I wrote the story with much deliberation about a Nonkilling ending, wondering how it would impact its two protagonists, the hunter and the hunted. Thank you Jocelyn.