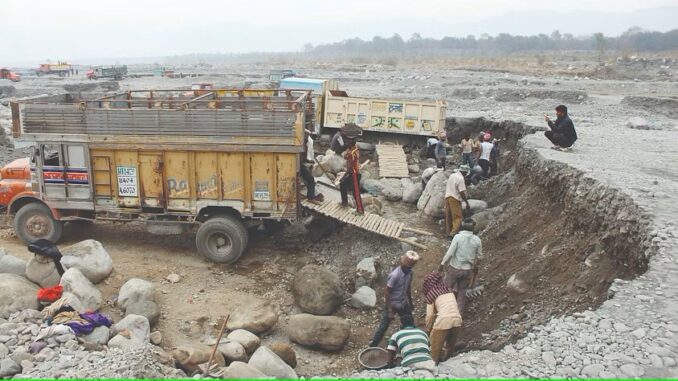

Workers extract sand, boulders and gravel from the Gaula riverbed in Uttarakhand. (photo courtesy: Dhruv)

Tapasya & Aggam Walia/ The Reporters’ Collective

T

he monsoons were approaching. Excessive rains were becoming a regular event every year. The rivers of Uttarakhand, long battered by humans, were lying low, waiting to hit back with flash floods. The state government should naturally have been worried about safeguarding people from the blowbacks of nature.

On 18 February, Uttarakhand chief minister Pushkar Singh Dhami met Union environment and forest minister Bhupender Yadav in New Delhi. What Dhami wanted was urgent permission to continue mining the rivers flowing through the state’s hills and forests, as permissions had already expired in January and the temporary extension was due to expire at the end of February.

What tempted the Uttarakhand government were profits from the sale of dug-up minerals, sand and stones, no matter its environmental costs. According to official records from 2016, the state made Rs 100 crore annually from mining just one of the four rivers that flow through the state. The value seven years later is probably much higher.

Five days after the meeting, the state government was granted permission, sidestepping critical legal requirements to conserve forests and protect rivers, as documents accessed by the Reporters’ Collective reveal.

One of the four rivers is Gaula, which is a lifeline for the state’s populous and commercially prosperous city of Haldwani.

The river, however, is dying. During the lean season, much of its length resembles a shallow and sometimes bone-dry nullah due to deforestation, excessive mining and pollution. The river had flooded in October 2021, leading to the collapse of a bridge and loss of agricultural lands. Between December 2020 and March 2022, three people also died by drowning in mining pits in the river.

The permission to mine was granted overlooking the errant miner’s history of flouting multiple norms as it dredged and dug up boulders, sand, gravel and minerals from the rivers over the past decade.

The Union government also went against multiple guidelines and court orders by giving in to the state’s greed to earn more from the river.

Also Read: Not far behind, Himachal too courts environmental disaster…

The state sought permission to mine Gaula in June—a monsoon month during which mining is prohibited to help the rivers recuperate from the deep scars of incessant mining. They received permission for that too.

While bending the law and greenlighting clearances through opportune interpretations of regulations is nothing new, it was rare for a chief minister to boldly proclaim his role in using influence to bend environmental laws.

This approval, secured at the eleventh hour, becomes even more remarkable considering the long gestation period typically associated with decision-making within the environment ministry.

“I thank the honourable Union minister for assuring swift action on my request,” Dhami wrote on Facebook immediately after the meeting. Five days later, Dhami thanked Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the Union minister in a Facebook post: “Under the leadership of the ‘double-engine government’, we are always working towards the development and prosperity of the region,” he wrote.

Gaula is one of the many rivers that feed the Ganga. During its course, the river carries stones, boulders and minor minerals from the mountains to the plains. In January 2013, the Uttarakhand Forest Development Corporation, a statutory body created by the state, was granted clearance to collect mountain debris from the bed of the Gaula river flowing through the forestland of Nainital district.

Though its mandate is to achieve conservation through judicious mining of riverbeds in forests to protect the forest land from floods, the state government’s company has succumbed to the allure of profit through excessive mining. The chief minister too had wished for the windfall the state could earn by mining in the prohibited monsoon month of June.

![]()

Gaula River

But as miners unscientifically scooped away tonnes of boulders, gravel and sand, they ended up removing stones that stood in the path of the water, which was now free to barrel down the river during the rains and take unprecedented paths—swallowing up farmland in its new course, smashing bridges and creating treacherous pits.

Before the last assembly elections, the state even relaxed the need to assess environmental impact when mining on private land and allowed stone crushers to operate at illegal sites for longer. It has also allowed excessive mining to train the course of rivers, in the name of disaster management and flood protection.

Experts have often warned that excessive and unregulated mining for short-term economic gains leads to long-term damage to life, ecology and property in the fragile Himalayan range.

Despite a bad track record and operating in such fragile zones—two red flags for any environment ministry—the corporation has had it easy with green clearances.

Forest land usage in India requires prior approval or clearance from the Union ministry of environment, forest and climate change. The approval is subject to conditions minimising environmental impact. In 2013, 1,497 hectares of forest land was diverted for mining the Gaula river. The permission to use the forest land for river mining (forest clearance) was granted for 10 years, till January 2023.

As the end date of the mining permission drew close, the state government sent a proposal to the Union environment ministry in April 2022, seeking an extension for the forest clearance. But the proposal didn’t go through as there were shortcomings.

Meanwhile, the state’s clearance expired on 23 January. Nevertheless, the environment ministry permitted river mining till 28 February by issuing a temporary working permission (TWP). Such permission is granted in cases where a state government fails to apply before forest clearance expires. The state had submitted the complete proposal three days late, on 26 January.

But the Union environment ministry flouted regulations in granting stop-gap working permission to the government in Uttarakhand. Prior to granting temporary permission, the Union government should have enquired if the applicant had a history of breaking forest conservation rules during its decade-long operation. The ministry was unaware of this because the state had filed an incomplete compliance report.

In the temporary working permission, the Centre asked the state to submit its latest status of compliance. The ministry went ahead and granted a temporary extension despite knowing full well that the toughest part of the environment clearance process is to ensure compliance with environmental safeguards.

The ministry had actually observed violations of environmental conditions. They found the state was lagging in compensatory afforestation, which is one of the most important conditions accompanying the Forest Conservation Act. It says the loss of forest due to any non-forestry purpose should be offset or compensated for by planting trees in an equal area of non-forest land or twice the area of degraded forestland.

The ministry also observed that there was construction in the areas where compensatory afforestation was supposed to be carried out, which is also against the condition that the land set aside for compensatory afforestation can only be used to grow trees. In its communications, the Centre highlighted that the state had not completed compensatory afforestation in time.

Sometimes approvals become negotiating tools depending on which company is on the other side. These can then allow for discretionary approvals for short or long term. And these become political or economic negotiations rather than conservation tools,” says Kanchi Kohli, a senior researcher on environmental law and policy.

So 10 days before the temporary approval was about to expire, chief minister Pushkar Singh Dhami, who also handles the mining portfolio, met the Union minister of environment and forests on 18 February.

On 23 February, despite acknowledging the poor compliance with previous conditions, the Forest Advisory Committee recommended the state’s proposal for extending the previous lease. The committee assesses and advises the environment ministry on proposals related to non-forest use of forest land. The recommendations are not binding on the Union government.

As it gave the state its go-ahead to mine Gaula, the committee again highlighted incomplete compensatory afforestation efforts and the state’s lack of interest in preparing a district survey report. Though it is a prerequisite for obtaining mining leases, the state hadn’t bothered to prepare one.

The committee also highlighted that due to poor compliance with forest conservation norms, the validity was being extended for only five years instead of the 10 years the state had sought.

“The violation of a compliance condition under the forest conservation law can amount to the violation of the law itself. What is the purpose of law if it’s openly flouted?” said Rahul Choudhary, an environmental lawyer who works with the Legal Initiative for Forests and Environment. “There is no use of forest conservation and environment protection laws and policy if those going against them are allowed to exploit resources and are given relaxations to do that,” said Choudhary.

To summarise words from the book Development of Environmental Laws in India by Kanchi Kohli and Manju Menon, environmental regulations don’t actively work to prevent damage to the environment but legitimise them by assigning economic values to it, like the Compensatory Afforestation Fund and the District Mineral Fund.

Uttarakhand too was specifically required to utilise proceeds from the sale of riverbed material for forest conservation. But it faced scrutiny when it attempted to scrimp on even the modest obligation by reducing the funds allocated for afforestation. The Forest Committee intervened and asked the Uttara-khand government to withdraw the orders and stressed that all the money should be used for forest conservation.

Additionally, while granting the five-year extension, the committee maintained that the state was supposed to use 50 per cent of its net profit for river training activities and forest conservation, but this compliance condition had also not been verified. Despite gaping gaps in meeting these conditions, the state was granted approval to continue mining and three months’ time to file compliance reports.

The most destructive among the relaxations granted is the permission to mine the Gaula riverbed in the monsoon month of June, even though the state was allowed to mine the river only from October 1 to May 31 according to the forest clearance given to it.

“During the monsoon, the flow of the river increases and runs on a specific course. But if mining is happening and the course is disturbed then the river can change its path and wreak havoc along the way,” Bhim Singh Rawat, associate coordinator of the South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People (SANDRP), explained.

Prohibition of riverbed mining in the monsoon has been reiterated by the environment ministry through its guidelines, and also by the courts. As per the Sustainable Sand Mining Guidelines, 2016, and the Enforcement and Monitoring Guidelines for Sand Mining, 2020, riverbed mining shouldn’t be permitted in the rainy season. For Uttarakhand, the 2016 guidelines earmark monsoon from June 15 to October 1.

But the state wanted to squeeze in more months into the mining calendar because, in its own words, mining in June meant an additional profit of Rs 50 crore.

In September 2015, the National Green Tribunal had directed that no mining be allowed in the rivers of north India during the rainy season. It instructed the environment and forest ministry to incorporate the condition while giving clearances. More recently, in May 2021, the Karnataka High Court cited the 2016 sand mining guidelines to disallow riverbed mining during the monsoon.

Since it started mining the river, Uttarakhand was allowed to collect 11.7 million tonnes of minor minerals from the river every year. Initially the state was only allowed to mine the middle half of the river, while preserving “one-fourth of the width of the riverbed along each bank”. In the new proposal seeking to extend the mining lease on forest land, the state government indicated plans to mine 70 per cent of the riverbed’s width, surpassing the 50 per cent it was allowed to.

The state had been instructed to limit the depth of mining to a maximum of 3 metres at the river’s centre. This depth should gradually decrease as the mining moves away from the river’s midpoint. But reports indicate that workers involved in river mining were unaware of this regulation.

In January 2016, the National Green Tribunal (NGT) imposed a ban on river mining in Gaula, in accordance with an earlier order that prohibited mining within 100 metres of either side of the Ganga and its tributaries. Several months later, Uttarakhand Forest Development Corporation faced a contempt case for illegal mining on the riverbed in violation of the NGT’s ban and was fined over Rs 10 crore.

“The Gaula’s health, ecology, fish life, whatever you want to call it, has been totally decimated. The labour rights of miners are violated. The river is mined excessively and it’s considered only a goldmine for the state that has totally given up on the river’s protection,” Rawat of SANDRP opined.

“It is not a river any more, it has just become a mining site,” he said.

******

(Courtesy: The Reporters’ Collective) Published 29 Jul 2023, 12:47 PM]. Original title:: Uttarakhand: The croros in the river

Leave a Reply