1.Introduction

I

n retrospect, throughout history, many works of literature could probably be considered peace literature (PL) but have not initially been conceptualized or recognized and classified as such. There are various possible reasons, one being a general lack of familiarity with PL as a genre as compared, for example, to literature of war (Munro). Another is limited intentional PL writing. Antony Adolf claims that

Writers seldom set out deliberately to write peace literature; it is the critics who apply this label, albeit infrequently. Self-aware ‘peace writers,’ ‘peace literature scholars,’ or ‘peace literature critics’ are rare. (9)

Fortunately, some scholars claim this is changing. As Urmi Chanda asserts in the subtitle of her newspaper article, “[PL] is the New Boom in South Asia.” Further, defining PL is not easy due to the complex idea of peace and its dynamic nature (Adolf 9). Perhaps related, some have a narrow understanding of the boundaries of PL, considering it, for instance, as only peace research, ‘propaganda,’ anti-war literature, pro-peace literature, or literature for conflict resolution.

This paper aims, therefore, to increase recognition of this potentially vast genre by describing it, showing how a work of literature can be analyzed through a close reading informed by a systematic conceptualization of peace, and in doing so, persuading readers the genre is a valuable and viable one, worthy of development and promotion, and soliciting support in this critical pursuit.

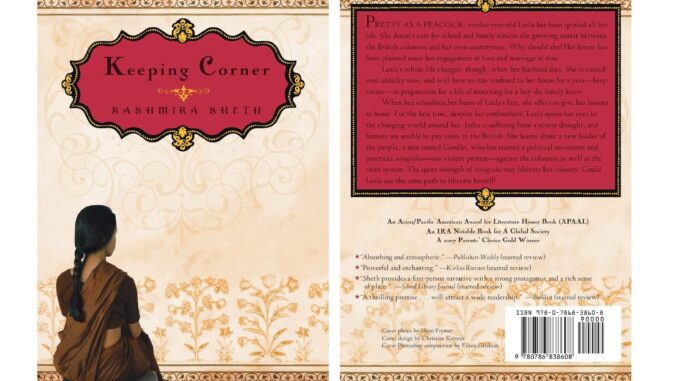

To start with, I adopt the stance that a commitment to peace implies not only research but also education and action (Galtung, “Twenty-Five Years” 148), and I use, this tripartite as the organizing framework. Thus, in this section, I share informative background (definitions and characteristics) about the emerging literary genre for a potentially unfamiliar audience. Then, in the main body, I present an analysis of a piece of historical literature for young adults, Keeping Corner by Indian-American novelist Kashmira Sheth (2007), that demonstrates valuable things PL does and can do. Finally, I summarize, discuss the value of this genre, advocate for its development and promotion, and briefly indicate ways of doing so in the last section.

Despite the long history of literature, literary scholarship focused on PL is relatively recent (Adolf 11). Certain attempts have, however, been made to describe the genre. I offer illustrative definitions and characteristics below.

To convey the nature of PL and honor it, I share three definitions from diverse perspectives. First, one psychotherapist and poet, the committed idealist María Cristina Azcona, writes in the Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems, Peace, Literature, and Art:

Peace Literature contains a pro-peace message. It has content: Peace as a high value. And an intention: To move and arouse ethical feelings and ethical emotions through the enhancement and exaltation of Peace through beauty in words. (274)

Also positive, the following poetic and visionary description comes from pioneering peace linguist Francisco Gomes de Matos:

My Literature for Peace

Literature?

Feelings, forms, functions

Ideas, genres, and texts

Persons, personas, and plots

In esthetic, creative contexts

Meanings, metrics, metaphors

Prose, poetry, points of view

Writers, poets, critics

Imaginatively what can they do?

Their attitudes, beliefs, and conflicts

Can be focused on facts, fiction, or force

Voiced through e-mails, epics, essays

In simple or mixed types of discourse

In verses, visions, and voices

New ways to be acquired

In songs, sonnets, and speeches

Irenic touches required

Let’s claim a brave, universal right

Well beyond creative imagination:

That of sharing sublime Literature

Aimed at profound humanization!

The final perspective, perhaps the most grounded and functional, by Adolf, the author of Peace: A World History, views

Peace literature as tragicomedic, doubly empathic and cathartic; as active in the limbic discursive spaces between epics and novels; as social acts that are pragmatic both philosophically and linguistically – these in no way disregard or discount the extensive and growing body of ‘peace literature’ embodied more broadly in scholarly articles, journalistic articles, books, blog posts, Tweets, interviews, videocasts, and so on. Peace literature as a genre does not rest upon formal or structural traits; it does, however, rest upon the consistent agreement and recognition of the people who produce, consume, discuss, and act upon that corpus. (14-15)

The above definitions provide insights into the form, function, intentionality, and content of PL. Gomes de Matos and Adolf state that PL is an eclectic genre. Indeed, diverse types of literature may compose the corpus of PL, and hybrids and new forms, structures, and discursive styles of fiction and non-fiction not yet imagined will certainly emerge.

Even though he offers a definition, Adolf questions the relevance of defining PL (9). He is more interested in “what peace literature, as a genre, does and can do” (15), perhaps what Neil Vallelly refers to as “literature as a verb” (53). In this regard, Azcona emphasizes affective aspects in “To move and arouse ethical feelings and ethical emotions … through beauty in words” (274) of PL. Meanwhile, in his call-to-action poem, Gomes de Matos advocates for PL to go socially “beyond creative imagination” (line 19), promoting “profound humanization” (line 21), through “irenic touches” (line 17). Comprehensively, Adolf indicates that PL can have a performative effect, both inward and out, which may be “tragicomedic, doubly empathic and cathartic … social acts that are pragmatic both philosophically and linguistically” (14). He emphasizes that PL evokes holistic reader response that “includes not only semantics, cognition, and affect but, above all, behaviour” (9). Thus, for these authors, PL serves transformative purposes albeit in different dimensions.

While Azcona highlights the author’s intentional focus, Gomes de Matos notes shared responsibility among writers, poets, and critics. More widely, for Adolf, identification of PL depends not solely on intentional writers, but on shared recognition of those who engage with it (14-15).

Aside from Azcona proclaiming a positive, moral aspect in “[PL] contains a pro-peace message” (274), little is said about the content of PL probably because, as Adolf states,

To ask what peace literature, as a genre, does and can do is to acknowledge that it is primarily determined not by its formal, structural, or discursive marks, but by substantive ones that can be explored and explained by criticism of the genre. (15)

Some PL works primarily constitute literature about peace while others constitute literature for peace. Certainly, PL can reflect diverse viewpoints (Adolf 11; White 1). However, for Adolf, “content and process are paramount” (12); some PL texts more successfully promote critical reflection and action (Paulo Freire’s praxis), leading to peace not only in but through literature (Adolf 17).

What then is peace? Early references to PL might have conceptualized peace as the opposite of war in the international arena (e.g. Weston Patton), and others emphasize ‘pro-peace’ (e.g. Azcona). Peace has a range of meanings and manifestations.

Johan Galtung, the disciplinary founder of Peace and Conflict Studies, systematically conceptualized peace over years, and I adopt his views here. In Peace by Peaceful Means, he sees peace as a perpetual process (90) as well as an “acceptable and sustainable outcome” (107), that of satisfying the basic needs of survival, wellbeing, identity/meaning, freedom, and ecological balance (197) via harmonious and associative means (61). Comprehensively, peace encompasses negative and positive transformative efforts inwardly and outwardly in individuals and collectives in multiple dimensions from the micro to the macro (30). Negative peace aims to reduce and eliminate direct, structural, and cultural violence1 (including threats) while positive peace concentrates on enhancing life (31-32, 197). Consequently, peace may be responsive/curative or preventive (1), respectively. Notably, peace does not imply the absence of nonviolent conflict, which is inevitable and can be constructive (70). Peace is, thus, complex, dynamic, and imperfect.

PL, then, is an eclectic and substantially vast genre with peace as its recognized focus and value orientation. Some works may be more comprehensive and address multiple dimensions and/or basic needs whereas others may concentrate on specific ones. Certain pieces may focus more on the outcome; others on the process, inwards and/or outwards. Meanwhile, some may emphasize negative peace, positive peace, or both.

2. Analysis

An early paper advocating for PL underscores the need for new ways to reach those unfamiliar with or generally uninterested in traditional PL to spread awareness of peace and to have an impact (Weston Patton 39). Adolf claims that “by integrating cultural studies and critical theory into already erudite, practical conflict resolution and peace studies” (10) we may “save and institute peace in its diversity” (10). Yet, still today, peace studies only occasionally includes the study of imaginative literature according to Robert S. White (1). Partly for this reason, I chose the fictional work, Keeping Corner by Kashmira Sheth (2007). Another reason for this novel is its comprehensive peace coverage. Finally, I want to give space and voice to an underrepresented type of literature since, according to Darshita Dave, “Children’s literature from India is not yet recognized around the world” (28, 29).

Having offered a brief rationale for my selection of Keeping Corner, which serves as the primary data source for this study and an illustrative example of PL, I provide contextual information about the author and the novel. Then, I discuss the background and present my interpretative analysis. Through this qualitative exploration, I hope to show that this is committed literature, literature as praxis, and demonstrate the value of PL.2

Sheth’s website indicates that she was born in Gujarat, India and was initiated to education in a Montessori school.3 She moved to Mumbai when she was eight and emigrated to the United States to study microbiology at college at seventeen. She grew up hearing and reading stories and especially appreciated historical fiction; she also liked to write. Fittingly, Sheth’s Author’s Note (297-288) and Author Interview (Vaughn Zimmer 297-298) reveal that Keeping Corner is a creative mesh of personal experiences and family-inspired stories intertwined with carefully researched socio-historical facts. Of particular significance to this novel are Sheth’s memories of meeting and hearing about a great aunt who was a child widow; another was learning about Mohandas Gandhi’s movement for independence. However, other aspects of Sheth’s “intimate lived experiences” (Short 41) also inform her writing.

In choosing this genre, Sheth continues a long cultural tradition of female storytelling albeit in written form (Superle 32). In her plot, she synthetically and synergistically weaves together “antithetical social conditions,” those of tradition and modernity, and fittingly since Adolf places PL in the category of epic novels.4

Due to her success, this historical novel has won awards, including an International Reading Association Notable Books for a Global Society in 2008 and a Best Books for Young Adults in 2009 (cover; American Library Association).

The story opens in Gujarat early in 1918, a year marked natural (drought), economic (rising prices and scarcities due to World War I), and political (increasing civil unrest between citizens and British colonists) hardship. It closes about a year and a half later, shortly after the 1919 Jallianwala Bagh massacre of citizens at a peaceful political gathering.

The protagonist, Leela, is a pampered 12-year old daughter of a middle class, Brahmin5 family in Jamlee, a rural village. Engaged at two and married at nine, she is expectantly awaiting her sending-off ceremony (anu), and her move into her husband Ramanlal’s home when he is fatally bitten by a snake leaving her a young widow who is to “keep corner,” that is, confine herself to her home for a year and prepare herself for a life of mourning.

Through vivid and imagistic description, this first-person narrative chronicles three phases: Leela’s colorful, joyful, and relatively carefree life leading up to her husband’s sudden passing; the dark and psychologically turbulent year when, due to tradition, she is “banished from [her] life, yet … learned to survive” (206) her imposed status of widowhood, dubbed a “living death” (53, 69); and her conflicted internal and external liberation and fresh start in Ahmedabad, where, by implication, she would pursue further studies and join Gandhi’s ‘freedom fighters,’ so her “life [would]n’t be wasted” (244). As the story unfolds, Leela confronts her confusing reality of tradition mixed with modernity and different responses to it.

In a parallel plot, the book relates Gandhi’s early efforts after returning to Gujarat from South Africa and settling in Ahmedabad to accompany6 disadvantaged and disempowered peoples (e.g. untouchables, poor farmers and laborers, women, and Indian citizens under colonial rule) in their attempt to redress violence (e.g. abusive practices and oppressive conditions, such as misery, exploitation, detention, discrimination, marginalization, and colonization) through peaceful resistance, insistence on truth and justice, and nonviolent action (satyagrah), and the quest for self-rule (swaraj) from the then government (sarkar).

The following interpretative analysis adopts Adolf’s broad definition of PL and Galtung’s comprehensive, systemic conceptualization of peace as the general guiding framework. As mentioned, Sheth’s choice of genre is congruent with Adolf’s description of PL as an epic novel. Regarding content, a close reading confirms the author is committed to peace; her substantial choices are not incidental. This analysis centers on: Sheth’s emphasis on peace in multiple dimensions; her realistic acknowledgement of the existence of diverse forms of violence; her deliberate inclusion of methods of nonviolent action in response to these; her pedagogical demonstration of pragmatic processes that lead to transformation; her careful selection of symbolic supporting details; and her clear promotion of peace values.

In Keeping Corner, Sheth foregrounds peace in everyday life in multiple dimensions.7 Regarding individual peace, she features clearly feminist8 characters, major and minor, including, notably, Leela’s progressive teacher (Saviben), who, disowned by her father for wanting to attend college when “a woman’s place was at home” (156), becomes a school principal, and later joins Gandhi’s struggle, and Leela’s caring brother (Kanubhai), who vows not to marry until she is free, declaring, “If I follow everyone in Jamlee, then I’d be just like them. … I am a man and make my own decisions” (221). Leela herself is described as becoming a “new Indian girl”9 by reviewers of the book (e.g. Dave 32; Superle 37), and she steadily develops agency as the story progresses. One character (Shani) is portrayed as “always happy” (162) while Leela’s aunt “Kaki was not a tall woman, but her heart and mind were strong” (28) as were Kaka’s, her benevolent uncle. Similarly, individual peace in Gandhi is depicted in the statement, “He may be a small man but he is fearless” (21). Each character experiences hardships and tensions, but they remain resiliently true to themselves.

In the interpersonal dimension, healthy and happy relationships abound. In addition to the devoted brother who goes “beyond tradition” (124) in looking after his sister and offering her hope and courage, the book features a compassionate mother (Ba) and caring mother-in-law who, it was expected, would “treat Leela like a daughter” (24), a father and son (Bapuji and Kanubhai) who do not see eye-to-eye but who overcome their disagreements nonviolently, and loyal, empathic, positive, and patient cousins (Jaya and Fat Soma) and friends (Shani). Sheth also includes loving, supportive, and generous couples (Shani and Lakha and Fat Soma and Puspa), a dedicated guru (Saviben), and a master (Bapuji) who respects and does not control Lakha, his “servant” (130).

Socially, daily peace is seen predominantly for those in the status quo, men more so than women, and higher class families more than economically disadvantaged ones. There are notable exceptions, such as inclusive education for Tara, a female student who is visually impaired. Pointedly, peace is represented in customs that are more humanizing for groups with alternative lifestyles. For instance, in communal living in Gandhi’s ashram, “people of different castes cook and eat together” (180) and even men help clean; “Everyone is a human being there” (180). However, peace is also illustrated in the ways individuals, such as the “Great Soul” (Gandhi) assume responsibility and take nonviolent action for human rights, groups gather around the kesuda tree, show concern for others, and unify around social causes, and community comes together for a cultural event (e.g. the janoi coming-of-age ceremony at the village hall).

At a more macro level, the events in the book coincide with the end of World War I. Prior to the armistice, Sheth highlights there being little support from locals to fight (alongside the British) with Leela’s aunt Masi’s proclamation summarizing the main stance:

Do you think Gujarati men would pick up arms, let alone use them? How will people who eat dal and rice because they don’t want to slaughter animals be able to kill human beings? Their parents will never give them permission to fight. (157)

Finally, peace with nature is also a strong theme. As seen, Leela’s people are vegetarian. Moreover, their care for animal welfare is evident in the way various characters feed, wash, massage, and even sing to their bullocks and in how their nonkilling ethic extends even to kalotars. Although one kills Ramanlal, later they carefully relocate another since “One thing we never did was kill snakes, or any other animals for that matter” (148). In other ways, too, they practice sustainable living (e.g. in reusing an old sari to make a blanket cover). The varied examples above showcase what White calls literature that “step[s] aside from conflict and presents peace as an alternative ethic in its own right and on its own terms” (2-3).

However, peace is not utopic; it is imperfect. Sheth realistically portrays this in Keeping Corner as Leela encounters or observes diverse forms of violence along her “unusual journey” (271) that affect survival, wellbeing, identity/meaning, and freedom needs. Even as the novel reaches its close, and Leela is “ready to make [her] future” (271), she acknowledges the probability of violence: “There were unknown dangers that would cross my path, hiding in the pleats of saris, in the turn of turbans, in the unknown eyes of the city” (258-259).

Leela confronts direct violence firsthand. Upon becoming a widow, she is forced to wear a plain brown sari (chidri) and remove all jewelry. Her glass bangles are smashed (albeit gently) off of her arms because “when your husband dies your fortune is gone” (54). Her head is also shaven. From the ninth-day ceremony following Ramanlal’s death, she cannot leave home for a year, and after finally being released, she is almost raped one morning as she fetches drinking water. Psychologically, Leela feels threatened when hearing authorities are confiscating properties and jailing resisters and witnesses direct violence against her family’s bullocks when “men in uniform” (128) take them because they refuse to pay taxes during the drought in solidarity with less affluent families. As well, she faces the threat of her family losing their livelihood: “The sarkar was taking the very things we needed to farm. If we couldn’t grow crops, sell them, and make money this year, we wouldn’t be able to pay taxes next year” (129).

Leela reads/hears about a local farmer who commits suicide due to tax-related financial hardship, families who carry out honor killings after daughters are disgraced, Gandhi’s arrest, and a mob burning government property (the telegraph and collector’s office). On a larger scale, she learns “Hundreds, maybe thousands, are dead or injured” (262) after the Jallianwala Bagh massacre and that public floggings take place the next day after citizens disobey a humiliating Crawling Order in response to “an assault on a white woman” (263).

As for structural violence, Leela’s life past, present, and future are monitored and controlled due to patriarchal cultural tradition, most notably from having to marry as a child, be a widow, act “like a proper widow” (66, 68), and remain one.

Socially, indirect violence affecting different socio-economic groups includes extreme poverty (e.g. for the untouchables), excessive taxation of farmers, and low wages for mill workers. Meanwhile, nationally, Indians are subject to authoritarian colonial rule. Indian participation in World War I is also structural.

Personally, Leela faces cultural violence, the kind that legitimizes others, especially in stereotypes and violent verbal and nonverbal communication. In her words, “My neighbor’s attacks were deadlier then [sic] a kalotar’s hissing” (151). Neighbors stare at her such that “Their eyes bit worse than the mosquitoes in monsoon” (217) and shun her, shouting “go in the house. No one wants to see the face of a widow before getting married. … It would be a bad omen” (210). Ideologically, until she gradually gains self-awareness and critical consciousness (Freire’s conscientizaçao), she experiences “interior colonization” due to patriarchal customs and traditions (Dave 30).

Oppressive behaviors resulting in discrimination against and dehumanizing treatment of various social groups are legitimized both by custom and law. For instance, different standards are evident in the treatment of social groups according to their respective statuses (e.g. Brahmin widowers can remarry, but not widows; however, Rabari widows are free). Similarly, literacy is not extended to everyone (e.g. Lakha and Shani), and citizens are allowed to be abused (e.g. jailed without evidence of wrongdoing) by colonial authorities due to the passing of the unfair Rowlatt Bill, which “Indian leaders opposed” (202), strict martial law, the Crawling Order, and censorship (in the form of government banned books).

As for manifestations of peace, violent ones, failing to fulfil basic needs, span various dimensions. Critically, rather than ignore or deny these, Sheth realistically represents them. Certainly, she does not celebrate them.

As the book closes, the line “An event can alter a person or a nation” (271) rings true. Throughout Keeping Corner, many characters experience transformations (peace as a process), most prominently Leela and Gandhi. Soon after Ramanlal passes, Leela wonders, “Was I going to become like [other widows] and melt into the darkness?” (63). However, the “journey [she takes] while keeping corner” (111) leads her to self-determination. Guided by Saviben and supported by family, she completes her compulsory education, earns a scholarship, and, self-sudfficient, leaves Jamlee to start anew. Similarly, after the Rowlatt Bill passes, Gandhi decides his people should not cooperate with the government “as loyal subjects of the British Empire” (171): “I can no longer render obedience to a power that is capable of such devilish legislation” (225). Committing instead to nonviolent disobedience, he changes tactics and, although the novel ends too soon, we know Gandhi’s inspirational and persistent efforts eventually earn India independence.

Although punctual events stimulate transformation, peace comes through praxis, critically reflecting on the roots of violence, creatively envisaging alternatives, and taking action. This section focuses on Leela’s reflection, specifically on her increased critical engagement, exploration of feelings, questioning of events, critical positioning, and ability to recognize complexity circumstances and reimagine them.

Initially, Leela has no interest in studying or social events, but her attitude changes. In the end, she thanks Saviben saying, “I’ll never forget the day you … offered to teach me. I didn’t really want to study then, but now I know it was the best thing that ever happened to me” (181). Similarly, her enthusiasm for reading the news increases. As she declares, “Saviben had made me read the newspaper for homework for many months, and now I was addicted to it” (190).

Throughout the story, Leela explores her feelings about her situation and the general social climate. After Ramanlal’s death, she sees herself as a victim, “tied with a chidri to the nail of widowhood” (153), and is full of negative emotions that transform themselves over time. For instance, she feels angry, in particular, about having to shave her head: “I realized that this was just a made-up rule, and something inside of me snapped. ‘I don’t want to follow this custom’” (59). Reflection on this injustice profoundly stirs her. Another time, due to jealousy, this preteen had thoughts of violating newlywed Shani: “I imagined savagely stripping her bangles, pulling her nose ring, yanking her necklace, and wiping her smile away” but acknowledged, “My thoughts terrified me” (142). When questioned about giving her the silent treatment, Leela reports, “[Shani]’s always happy, and it makes me miserable” (162). After Kaki prompts, “So you try to make her unhappy by being rude?” Leela realizes she is being unfair and, subsequently, takes responsibility for her behavior which improves their relationship.

At first, Leela doubts that anything can change socially: “Gandhiji can keep on writing, but do you think anyone cares about being fair?” (77). Later, she develops hope and conviction as she sees evidence of change. In another case, she expresses ambivalence. For instance, when Bapuji states, “The collector has promised [to] waive taxes for poor farmers, if the ones who can afford to pay do” (133) and the newspaper reports the strike successful, Leela admits, “I wasn’t sure how I felt about it. We lost Mani [a bullock] … Lakha had been humiliated, and in the end we paid our taxes anyway. Trying to influence the sarkar had cost us too much” (133). While concluding that following tradition is easier than change, she concedes, “Maybe there was a victory in the defeat” (133) since Gandhi had united the farmers to challenge the government.

More positively, Leela experiences empathy for others and dual perspective as her reflection on Gandhi’s fast shows: “It must have been hard to go hungry” (96).

Leela constantly asks questions as she reflects on different circumstances. She questions individual actions like her father’s, “I thought about how Bapuji felt about satyagrah. It made me wonder. If Bapuji was for truth and fairness, then he should know that what was happening to me wasn’t fair. Why didn’t he fight for me?” (86-87). While Leela mostly appreciates Gandhi’s work, she is troubled by his cooperating with the colonial government regarding the war efforts: “Gandhiji’s insistence about enrolling in the British army confuses me. … why is Gandhiji asking us to take up arms? Has he changed his mind about nonviolence?” (125).10 She questions policies such as conscription as in a letter to Jay, “Since the Engrej rule us, we have to follow their commands, but if they don’t force us to fight in the war, why should we volunteer? If no one is attacking us, why should we want to kill them?” (125) and the government’s role in killing citizens who had “gathered peacefully to listen to political speeches” (261) as her reflection displays:

It was as if all of Jamlee felt Punjab’s pain, humiliation, and sorrow. The massacre and what followed made us realize that the British did not value our lives. How could we support the Raj that had killed our own so mercilessly? (264)

Leela also questions the merit of certain traditions. In response to Kaki saying, “we have no choice but to follow the custom” (59) regarding shaving her head, Leela asks, “Who started this? And why? Can anyone benefit from it?” (59).

As Leela gains critical consciousness, she takes stances, for example, when no response is taken where one is expected. After nearly being raped, she overhears a conversation which helps her identify her attacker. Later, Kaki admits she “had a feeling [it was him]” (251). As Leela pushes for an explanation concerning inaction, her aunt reports, “they are afraid it would taint the victim more than Batuk” (251), and advises her to rest. Struggling to sleep, she thinks,

There was something terribly wrong … I couldn’t understand how the people of Jamlee tolerated men like Batuk. They should have been enraged. They should have wanted to protect their sisters and daughters from him. Instead, they were silent. … and they let the victims suffer. By ignoring such brutality, people were just as guilty as Batuk and others like him. (251-252)

Shortly after, she leaves for Ahmedabad, and the closing lines show her resolve not to be a bystander: “Was it time to join [the people making a different destiny for our country]? I took a step” (272).

Over time, Leela begins to understand causes and effects, and how actions and happenings are complexly interconnected:

When I first started reading the news, it made no difference to me how the farmers were doing, what our leaders did, or who won or lost the war. Now, I understood that events were like the spokes of wheels. Even if a single spoke did not seem critical, it was still part of the wheel that moved the world. (190)

This shows she develops systems thinking.

Urvashi Sabu states,

Literature is not just a reflection of society’s past, present, or future. It is also an imaginative record of what society and its human constituents can become; of the heights of nobility, generosity, kindness, and empathy that human beings are capable of achieving in the face of all odds (2) and White notes, “To create a better world, we must first envisage one” (4). As seen, peace is not always enacted by all characters in Keeping Corner; nor is it always found. Young Fat Soma renounces the world when forced to remarry immediately after the devastating death of his second wife. Nevertheless, the possibility of peace is imagined in various places. Indeed, in Fat Soma’s case, he decides to seek nirvana: “Like the Buddha, he had decided to take this path to find peace” (230).

When Leela narrates hearing

Daughters are someone else’s treasure, and the sooner you part with them the better off you are; daughters look good only in their in-laws’ house, and the younger you marry your daughter the quicker you’re done with your obligations (9)

she contests this: “I don’t think those things are true. I can’t imagine my family being relieved on the day they give me my anu” (9). She imagines peace in contrast to others’ understandings of reality.

At various points, she also imagines peace contrary to her own experience. For instance, following caste tradition, Brahmins would not normally eat or drink food prepared by another caste. Leela cogitates over her current situation,

I’d always make tea and pour it in the cup that Shani brought with her” but notes, “if we both lived in the ashram, I could drink the tea that Shani made, and we would share our utensils. [Moreover, if] there were no difference between us in the ashram, then I would be able to marry again, just like Shani had. (193)

Leela is naturally hopeful. Even in dark times, she senses, “like rain transforming the earth … my life could change” (81). She envisages possible futures for herself: “I could be like Saviben and help other girls. Then I wouldn’t be going through life as Leela the widow – I’d be Leela the teacher” (146). These imaginings provide constructive outlets, even if solutions are not easy.

In many ways, Leela’s reflections change her world. However, as Allsup states, reflection alone is insufficient: “To have hope, we must disavow the indifferent, the fixed, the silent. Praxis requires us to act” (167).

In Keeping Corner, Sheth cleverly prioritizes methods of nonviolent action. Preventing and responding to violence are core aims. Two actors engage in activities for individual peace. Bapuji does daily meditation, and Kaka sings devotional songs (bhajan).

Leela’s parents model a strong ethical orientation as evident in Ba’s response to gossip about letting her go: “Even if people talk, we have to do what’s right” (237). When Leela hears that local government officers are beaten after a popular riot takes place following Gandhi’s arrest and remarks, “They were horrible,” her father replies, “It doesn’t matter. Nonviolence means you must show restraint” (234).

Some characters show restraint. Kanubhai’s relationship with various family members is tense due to disagreements about Leela’s treatment and future. Nevertheless, he controls his anger in negotiations; his (sometimes heated) arguments with Bapuji mostly involve long talks. Kanubhai also bites his tongue to avoid unnecessary verbal conflicts with Ba, as this turn indicates, “He started to say something to her, then changed his mind” (176). His persistence in helping Leela indicates his commitment to both the outcome and process, to peace by peaceful means.

Examples of peaceful protest appear in various dimensions as characters stand up to injustice to protect others. Kanubhai exclaims when he sees Leela: “Ba, Kaki, what have you done to Leela? She is … she is just a child! Did you have to shave her head? … I know it is custom, but you don’t have to follow it. This is a crime!” (69). As seen, he stays with her, promising to assist. Another time, when a government man hits the animals with a staff, Lakha intervenes saying, “You’ll have to hit me before you hit her” (129). After being pushed, seeing the animals hit again, and being threatened, Lakha grabs his sleeve and roars, “If you so much as touch her again, I’ll scream until the whole town is here … if you are cruel to animals, people will not hesitate to use [nonviolent] force to stop you” (130). In defense, Bapuji adds, “If he sees cruelty or unfairness, he has every right to protest” (130).

Gradually, Leela develops the skill of persuasion and finally solicits Ba’s support:

Gandhiji thinks widows should be able to go to school. Narmad said the same thing fifty years ago. What good are all their ideas if widows and their families don’t take the lead? Ba, I want to study, and I need your help. (236)

After, she appeals to her father with a decisive argument:

whether it is against the foreign government or our own society … we have to take a pledge to fight against all that is wrong and cruel, including customs and prejudices. Don’t our scriptures, Vedas, say that truth is whole? So how can we fragment it? How can we fight against cruelty and unfairness in some cases but not in others? (246)

Bapuji goes from “We are done talking about this subject forever” (242) to “Leela, Kanubhai fought for you, but he couldn’t convince me that your going away to school was a good idea. You made me realize that this is not just about you, it is also about something bigger” (246-247). Leela is, thereby, able to bring about change and “honour tradition by working from within” (Superle 33).

Besides these examples, Sheth’s novel is replete with nonviolent actions Gandhi and followers take that span numerous categories from Gene Sharp’s seminal work.11 Gandhi himself engages in and encourages forms of protest and persuasion. He holds public assemblies, makes public speeches, and pronounces declarations, like when “He denounced the Rowlatt Act as the Kalo Kaydo, Black Law” (232). He produces public communications, including interviews, newspaper articles, letters to the press, and books. Representing various groups, Gandhi attends meetings and appeals to the government (e.g. to waive taxes), advocating on their behalf. As well, he performs symbolic public acts (e.g. wearing a white dhoti or a rough, handspun khadi).

Gandhi also promotes and engages in methods of economic noncooperation including peaceful agricultural strikes, protest strikes (e.g. at the mill), and a complete shutdown (hartal) “for observance of humility and prayers” (225). He encourages farmers to resist by pledging not to pay taxes, a kind of economic boycott.

Methods of political noncooperation include disobedience as in rejection of authority. For instance,

When the sarkar threatened to arrest [Gandhi] if he didn’t return home – saying he was an outsider in Bihar – he replied, ‘You have come from five thousand miles away and consider yourself insiders, but I am an outsider because I have come from Gujarat? I will not obey your order’. (22)

Later,

Gandhiji and the volunteers sold two books in the streets of Mumbai. … Hind Swaraj, Indian Self Rule, and Sarvodaya, a Gujarati adaptation of John Ruskin’s book of social criticism, Unto This Last. … Both books had been banned by the government, and people had been warned that they could be arrested and jailed if they bought them. (232-233)

Through this action, he raises funds for “future demonstrations of civil disobedience” (233).

Various methods of nonviolent intervention are also used from the successful hunger strike (a psychological intervention) Gandhi leads “until the mill owners and the mill workers settle their dispute [over a pay raise]” (74), and social interventions proposing alternative institutions such as his ashram and a “national school” (203), which is gender inclusive, with men and women studying as “equal partners” (204), and adopts a holistic and seemingly culturally sustaining pedagogy12: “using [their] mother tongue as the language of instruction, learning Hindi and English, and using the opportunity to study a variety of subjects” (203-204).

Other examples of engagement in nonviolent actions include individuals resigning from posts and renouncing honors: “Many successful lawyers, like Dr. Rajendra Prasad, had given up their lucrative practices to join Gandhiji. The Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore had returned his knighthood to the King-Emperor in protest” (272). Collectively, the people of Gujarat do not support conscription.

The acts of advocacy and activism signaled active responses to violence as well as a strong ethic of nonviolence. However, critically, as the author shows, there are occasional lapses in nonviolent action. In self-defense when Leela is about to be raped by a tailor, she resorts to using the khilli her aunt gave her, although, notably, the pin is made of gold, so it would not infect. In another case, followers riot upon Gandhi’s arrest. As Leela notes, “Even Gandhiji couldn’t control people’s emotions and actions. … [Fortunately, he] returned to the ashram immediately, and miraculously was able to restore peace” (235).

Besides her choice of genre and the categories analyzed above, in Keeping Corner, Sheth carefully and consistently chooses to highlight symbolic details that span various areas and reinforce peace. Thanks to “the rich details of daily life and culture” afforded by her insider perspective (Short 41) and her careful research into (peace) history, Sheth seamlessly transports us in place and time. We travel to Gujarat, where she and Gandhi are born, and the campaign which leads Gandhi to become the Father of the Nation begins.

As shown, Sheth demonstrates her intention to peace through rich and complex characters who are not static and passive but who transform and demonstrate initiative and agency. Even the men who confiscate Leela’s bullocks “following the sarkar’s order” (130) apologize in the end: “The sarkar had taken so many animals that it was impossible to care for them properly. We’re sorry your calf died” (133).

The use of juxtaposition in contrasting characters (sisters, mothers-in-law, father and son, and various types of widow/ers) that coexist serves to represent a plurality of perspectives and experiences for reflection all the while ensuring what Adolf claims is “an important aspect of what peace literature does and can do, namely, create unity in diversity” (9).

In addition to Gandhi’s strong example of nonviolent action, Sheth casts “pioneer women” (156), the first woman doctor in Mumbai and Saviben, as influential role models for Leela. Saviben’s role as educator is especially important for she embodies peace education in her transformative, learner-centered teaching style (à la Montessori). She demonstrates critical pedagogy (à la Freire), an ethical and dialogic approach rooted in praxis, and encourages holistic and experiential learning through sensory observation (à la Dewey). As Saviben educates Leela about and for peace, she prepares her for an education that is lifedeep, lifewide, and lifelong. Sheth’s choices here may reflect her own educational upbringing.

More explicitly, the author states,

I grew up reading Gandhian literature, and most of my teachers were freedom fighters who participated in satyagrah. Naturally, I wanted Narmad and Gandhiji to shape Leela’s thoughts, and for her journey to parallel that of India’s struggle for independence. (Vaughn Zimmer 288)

Gandhi and the Gujarati poet and philosopher Narmadashankar Lalshankar Dave, however, are not the only cultural referents cited in the story. Sheth ensures characters refer to prominent and inspirational cultural gods such as Lord Ganesh, who removes obstacles, Lord Krishna, who spreads love and compassion, and Saraswati, who represents knowledge and the arts. The nearby temple, Ramji Mandir, is named after the god Leela’s family prays to when seeking solace, Lord Rama, who protects. As well, when Leela’s uncle offers her a blessing to continue her studies, he says, “May you become as learned as Arundhati” (247).

Sheth chooses to include excerpts from the sacred Gayatri Mantra, seeking “excellent understanding” (239), and mentions Narsi Mehta’s bhajan. Through the “tissues of citation” (Dewi 19), the intertextuality within the novel, the author shows how peace work is carried out through various forms of fictional and nonfictional literature, like newspaper articles, political speeches, epics, poems, letters, sacred mantras, and devotional songs.13

Even the choices of holidays are meaningful. For example, Leela reflects on a potentially awkward interaction (between conservative Masi and progressive Saviben) and makes the point that “On New Year’s Day we were supposed to overlook our differences and embrace each other with open hearts” (181). After Diwali, the festival of light, Leela penned in her notebook that “The whole world seems brighter” (183).

Finally, Sheth employs positive and negative peace linguistic approaches. For instance, she refers to Gandhi’s empowering multilingual educational agenda, validates translanguaging by introducing local Gujarat words, texts, and dialect into the novel, supported by a helpful glossary, and aims to reduce violent language use by questioning stereotypes (e.g. related to gender and widowhood) and calling out forms of linguistic injustice and humiliation. For example, when Masi curses Leela with “Hear me raandi raand!” (103), Leela narrates that “it was as if she had sprayed me with filthy water … Just because I was a widow didn’t mean she could insult me and make me feel worthless” (103). Sheth also promotes critical literacy, a valuable skill for peace, through Leela’s growing enthusiasm for reading and her teaching of Shani. Overall, peace symbolism in the novel is rich and varied.

Peace as a process is guided by and reflected in values and visions of desirable outcomes. Throughout Keeping Corner, as surely evident by now, Sheth conveys universal peace values as various as life, love, generosity, compassion, well-being, hope, courage, truth, nonviolence, fairness, equality, justice, harmony, inclusion, unity, partnership, solidarity, and sustainability, highlighting “Universality – in actualities or aspirations – … what peace literature, its study, and its pedagogy seek to reclaim” (Adolf 11).

3. Conclusion

Keeping Corner has already been recognized as a feminist piece of literature (e.g. by Dave and Superle). The novel does not yet appear to have been classified as PL. However, “It is the peace literature critic’s function to provide new insights into … those parts of world literature that may constitute peace literature” (Adolf 17), and I contend that this novel has a strong peace orientation and reading.

In writing her novel, Sheth critically and creatively engages in peace work aimed at “making a different destiny” (272) bottom up. Her commitment to peace in and through literature are evident not only in her choice of genre, but especially in her comprehensive peace coverage.

The content plots two major stories of peace (and several minor ones) while centering peace in multiple dimensions and varied forms, processes of reflection and nonviolent action to achieve these, other peace symbol, and associated peace values without failing to acknowledge the existence of diverse forms of violence. Sheth does so by drawing on offerings from disciplines within peace studies (e.g. peace history, peace action, peace education, peace journalism, peace literature, and a newer branch, peace linguistics).

Besides parallel plots and foregrounding, Sheth masterfully uses techniques such as exemplification and role modeling, juxtaposition (contrasting characters), intertextuality, translanguaging, and symbolism to promote peace. Through her peace work, her literature about and for peace, Sheth does what Sharon Rab, founder of the Dayton Literary Peace Prize, states:

Writers inspire us and infuse us and show us how to work as allies with them to build a better world. They go into the quiet of a room, and they shape truth with words – words that can then help us be our best selves. They also create a place in time and a moment that will allow us to consider how to build peace one word, one book, one discussion at a time. (7:53-8:29)

This paper presents a close reading of only one piece of PL, Keeping Corner. Nevertheless, through this illustrative example, we see how PL can raise awareness of both the pervasiveness and desirability of peace and, simultaneously, ways of reaching and sustaining it. Others (e.g. Adolf) have already argued that PL has empathic and cathartic effects. Indeed, just as peace can be therapeutic (Galtung, Peace by Peaceful Means 29-30), PL can serve as a “literary intervention” (Adejumo 20), not only personally but socially, as illustrated in Leela’s, Gandhi’s, and other characters’ transformative cases. PL “highlight[s] the need for citizens to acknowledge personal responsibility for their actions” (Munro) and functions as “a vehicle for social change” (Cosgrove 234). It can serve historical purposes as “in the safeguarding of memory and commemoration” (Munro) as well as imaginative ones (Sabu 2).

PL is not yet a well-known genre, but it has the potential to play an important role in promoting peace, positive and negative, in multiple dimensions so long as we take action (Cosgrove 237, 238). This requires further research, education, and action. Allsup describes praxis, as “not simply the capacity to imagine alternative scenarios, but … the slow burning fuse of possibility and action” (157). Just as “ideas sank into [Leela’s] mind like monsoon rain into soil, [and] thoughts began to grow” (163), I hope this paper sows healthy seeds and produces an abundant and sustainable PL ecosystem.

While writing this paper is itself a form of activism, I would like to advocate for more PL and solicit support in its development and promotion. Ultimately, as Adolf writes, the influence of PL depends on recognition (15), so awareness of, exposure to, and engagement with the genre are essential. Diverse actors can play constructive roles in imagining, creating/writing, identifying, developing, critically reviewing, translating, adapting, prioritizing, soliciting, marketing, disseminating, curating, sharing, and educating about, through, and for PL. Although it may take time and effort, a concerted approach would be impactful. As Munro states, “we need more writing like this, and we need it urgently.”

Works Cited Adejumo, Ade. “Peace Literature as an Alternative Reality: The Challenge of Contemporary African Writer.” International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention, vol. 3, no. 9, 2014, pp. 19-22. Adolf, Antony. “What Does Peace Literature Do? An Introduction to the Genre and Its Criticism.” Peace Research: The Canadian Journal of Peace and Conflict Studies, vol. 42, no. 1-2, 2010, pp. 9-21. Aharoni, Ada. “The Necessity of a New Multicultural Peace Culture.” Dve Domovini: Two Homelands, vol. 19, 2004, pp. 69-86. Allsup, Randall Everett. “Praxis and the Possible: Thoughts on the Writings of Maxine Greene and Paulo Freire.” Philosophy of Music Education Review, vol. 11, no. 2, 2003, pp. 157-169. American Library Association. “Keeping Corner.” 2023. www.ala.org/awardsgrants/content/keeping-corner. Azcona, María Cristina. “Peace Education Through Literature.” Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems, Peace, Literature, and Art, vol. 1, edited by Ada Aharoni, EOLSS Publishers/UNESCO, 2009, pp. 262-288. Bajaj, Monisha. Encyclopedia of Peace Education. Information Age Publishing, 2008. Chanda, Urmi. “How Do You Recognise ‘Peace Literature’? It is the New Boom in South Asia.” The Print, 22 Jan. 2023. https://theprint.in/opinion/how-do-you-recognise-peace-literature-it-is-the-new-boom-in-south-asia/1327439/. Cosgrove, Shady, E. “Reading for Peace? Literature as Activism - An Investigation into New Literary Ethics and the Novel.” Activating Human Rights and Peace 2008 Conference Proceedings, edited by The University of Wollongong, 2008, pp. 233-239. Dave, Darshita. “Celebration of a Girl’s Journey from ‘Interior Colonized’ to Liberated Self: Kashmira Sheth’s Keeping Corner.” International Journal of English Literature, vol. 4, no. 2, 2023, pp. 28-32. Dewi, Novita. “Positioning the Chinese Princess of Peace in World Literature.” Journal Pendidikan Bahasa dan Sastra Indonesia, vol. 4, no. 1, 2019, pp. 18-23. Farmer, Paul. To Repair the World: Paul Farmer Speaks to the Next Generation, eBook, edited by Jonathan Weigel, University of California Press, 2013. Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Penguin Books, 1970. Galtung, Johan. Peace by Peaceful Means: Peace and Conflict, Development and Civilization. Sage, 1996. ---. “Twenty-Five Years of Peace Research: Ten Challenges and Some Responses.” Journal of Peace Research, vol. 22, no. 2, 1985, pp. 141-158. Gomes de Matos, Francisco. “My Literature for Peace.” www.humiliationstudies.org/intervention/peacelinguistics.php. Henry, Patrick, and Richard Middleton-Kaplan. “Using Literature to Teach Peace.” Peace Research: The Canadian Journal of Peace and Conflict Studies, vol. 42, no. 1-2, 2010, pp. 142-166. Munro, Niall. “Towards a Literature of Peace.” Diplomatic Courier. 27 June 2016, www.diplomaticourier.com/posts/towards-literature-peace. Paris, Django. “Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy: A Needed Change in Stance, Terminology, and Practice.” Educational Researcher, vol. 41, no. 3, 2012, pp. 93-97. Rab, Sharon. “Words Matter: Sharon Rab at TEDxDayton.” YouTube, 19 Feb. 2014, youtube.com/watch?v=JiPrwGGs3KA. Sabu, Urvashi. “Inculcating Peace Through Literature: Towards an Evolved Pedagogy.” Samyukta: A Journal of Gender and Culture, vol. 6, no. 2, 2021, pp. 1-9. Sharp, Gene. The Politics of Nonviolent Action. Porter Sargent, 1973, 3 vols. Sheth, Kashmira. Keeping Corner. Disney-Hyperion, 2007. ---. “A Snapshot of Kashmira.” 2006. https://kashmirasheth.typepad.com/my_weblog/biography/. Short, Kathy, G. “The Significance of Perspective in Exploring International Literature with Educators.” WOW Stories, vol. 3, no. 2, 2011, pp. 38-46. Trites, Roberta Seelinger. Waking Sleeping Beauty: Feminist Voices in Children’s Novels. University of Iowa Press, 1997. Vallelly, Neil. “(Non-)belief in Things: Affect Theory and a New Literary Materialism.” Affect Theory and Literary Critical Practice: A Feel for the Text, edited by Stephen Ahern, Palgrave Macmillan, 2019, pp. 45-64. Vaughn Zimmer, Tracie. “Discussion Guide.” Keeping Corner, by Kashmira Sheth, Disney-Hyperion, 2007, pp. 292-299. Weston Patton, William. “The Drama and the Peace Movement.” The Advocate of Peace (1894-1920), vol. 77, no. 2, 1915, pp. 38-40. White, Robert. S. “Literature and Peace Studies.” Pacifism and English Literature: Minstrels of Peace. Palgrave MacMillan, 2008, 1-12.

********

Thank you Jocelyn Wright. Footnotes not included for reasons of brevity. For the complete text see original in Academia here: tps://www.academia.edu/104169635/Literature_as_Peace_Work_Eyes_on_Kashmira_Sheths_Keeping_Corner

Jocelyn Wright teaches at Mokpo National University in the Department of English Language and Literature 1666 Yeongsan-ro, Cheonggye-myeon, Muan-gun, 58554 Jeonnam South Korea Her interests include peace linguistics, peace language education, peace literature

Excellent contribution to Peace Studies. Kudos on pioneering a genre!

Thanks for your encouragement, Bill!