You leave the mothership named Columbia after Jules Verne’s fictional moonship, stand in a cramped Lunar Module with a fellow astronaut, and head-descend on the moon. Nearing the lunar surface, the computer sounds the alarm, you are running out of fuel, and this trip has no contingency plan. It’s either land or abort the twenty-billion-dollar mission. Soon the red warning light comes on with only 115 seconds of fuel. You override the computer, take over the controls, and descend into a moving fog as the dust sweeps away in great arcs for miles. Thirty seconds later, you touchdown at the Sea of Tranquillity and wait for the dust to settle. After 3.7 billion years of waiting, precisely fifty-four years ago, the first sign of life appeared on the Moon, and it was from Earth.

With 360 pounds of Spacesuit on Earth but weighing only 60 pounds here on the Moon, you slowly descend the nine rungs. At the last step, you pause and start the camera that takes you into the black & white screens of half a billion viewers worldwide. Four days, six hours, forty-five minutes, and thirty-nine seconds after leaving the Earth, you step onto the moon, raising symmetrical arcs of fine lunar dust. As your left foot touchdowns, you repeat what you had rehearsed: “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” Famous eleven first words from Apollo 11, that encapsulated an era.

Neil Armstrong was not one to wax poetry; he was adept at computerese. While other astronauts preferred country music, his playlist en route was the spacy Music Out Of The Moon: Music Unusual Featuring The Theremin. If we would say “we,” he would say, “a joint exercise has demonstrated”; you did your best, but he would obtain “maximum advantage possible.” However, the moon mended his language by overwhelming him: he had planned to say twelve words, but in the excitement, he forgot to utter a crucial syllable, the indefinite article “a” before man. “Damn, I really did it,” he later said, “I blew the first words on the moon, didn’t I?” He did, fortunately. With that omission, Armstrong’s small step (not just the metaphorical leap) was that of the entire humankind.

In 1969, we in India were not part of the half-billion viewers (out of 3.5 billion) that watched the moon landing globally. I was a high school student home from Ooty for a holiday, desperately twirling the knobs of our large Grundig cabinet radio to hang on to the waves of Voice of America broadcasting the moon landing live. There was so much static that I never heard that famous sentence. However, NASA’s jubilation left no doubt when Neil Armstrong stepped on the moon at 8:26 am on July 21st in India. The elation has lasted a lifetime (undampened by contrarian theories).

Before the sun rose at 6:11 am that day, past midnight, when everyone else at home had fallen asleep, the lunar module had already landed (but the astronauts had not emerged). I had come out in the front garden of the bungalow. The sea was calm as the high tide that night had subsided.

I looked up and saw the moon in the sky, and it felt uncanny that two human beings were up there. By their presence, at that instant, the moon became personal:

Cosmos

Universe perpetual motion machine

Milky Way spinning white frisbee

Solar System fleck of milk cream

Sun yolk of the cosmic egg

Earth drop of water blue

Moon ping-pong ball

Love all!

The egg, resembling 0, is L’œuf in French and pronounced close to “love.” – hence the score 0 in table tennis and the score of indefinite amnesia of both the astronaut and poet. The astronaut at the end of his journey and the poet at his beginning lapsed with their indefinite articles, which turned them into universalists. When I did reinstate the indefinite article decades later, it turned the particular to the mother-of-all universal in my shortest poem to date with all the words circumambulating it:

Universe

Is a uni

Verse

“Verse” is from Latin versus from PIE root wer-“to turn, bend,” or to plough from one line to another, vertere = “to turn” as a ploughman does. It returned the Universe to the very ground under our feet. Standing, or in Vulgar Latin, stantia leads to Stanza. To dwell on Earth, indeed in the Universe, is to dwell poetically. That realization led to a long calligraphic poem, The Domain of Inbetween. The astronauts’ yearning for Earth led to To Planet No. 3.

I not only missed the indefinite article in my earlier poem, but I also missed the astronauts when they visited my city that year, as I had returned to my school in Ooty. However, I saw the moonrock on display later at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research. I was struck by how ordinary the grey rock, as dark as basalt, appeared. The crystalline and luminous moon was an act of imagination filtered by our vision. It truly belonged to us as imaginative beings. Hence the perceptive Ibn-e-Safi:

![]()

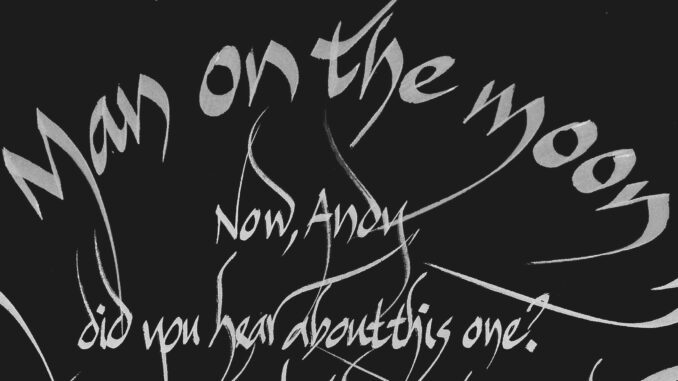

The R.E.M masterpiece album with a Sinbad Star on its cover, obsessed with death (“Readying to bury your father and your mother / What did you think when you lost another”). Inside, Man on the Moon was Michael Stipe’s poignant tribute to the late Andy Kaufman, who, it was suspected, faked his own death. Andy excelled at faking the fake to reveal the truth via his double and triple-fakes. The melody lay at the melancholic heart of modernity (I think, therefore, I am only as long as I don’t think either about thinking or about the consciousness of us conscious beings). If you believe the refrain “If you believe…” means Michael doesn’t believe in the Moon landing, think again. It is an Andy move: Michael, following Andy, is faking the fake. He is tongue-in-cheek faking skepticism. The lyrics are a tease that turn the moon landing itself into an act of our imagination.

![]()

While moonwalking wearing lunar overshoes, Neil Armstrong reported to Earth, “I can see the footprints of my boots and the treads in the fine sandy particles.” Those fine lunar particles were jagged enough to support footprints without needing moisture. Those footprints were turning the metaphorical into literal as they were being made on the sands of time with no atmosphere to erase them.

His pristine footprints endure on the Moon.

![]()

Author’s note: Sifting Moon landing conspiracy theories from physics led to winning the CBC Passionate Eye “Dark Side of the Moon” 2003 documentary contest. The prize was a boxed set of the complete works of Stanley Kubrick, that in turn, resulted in a post-professional dissertation done across a single semester teasing out celluloid labyrinths. The dissertation:

the poems:

-

Domain Of Inbetween, (calligraphic) as well as

-

To Planet No. 3

and the three calligrams inscribed for this essay:

can all be downloaded from Academia. In the essay, Neil Armstrong’s footprint and other quotes are from Norman Mailer, “Moonfire: The Epic Journey of Apollo 11,” Köln: Taschen 2019. For competing theories of Moon Landing, see National Space Centre Discovery Director Professor Anu Ojha’s talk at the Royal Greenwich Museum (rmg.co.uk).

Architect-Poet-Calligrapher H. Masud Taj lives with his family in Ottawa, Canada and visits India usually during the monsoon.

This author in The Beacon.

Leave a Reply