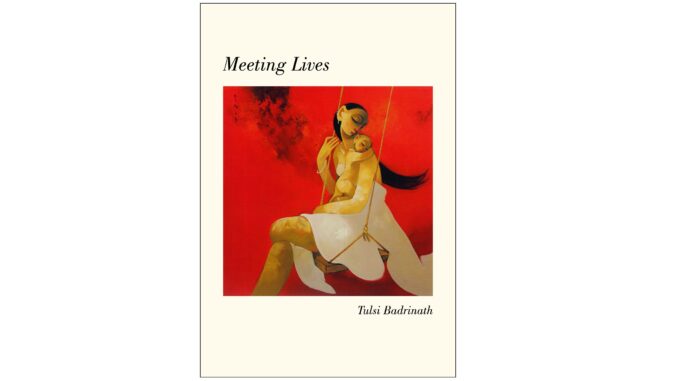

Meeting Lives. Tulsi Badrinath. Niyogi Books Pvt. Ltd. November 2008. 244 pages

S

anju is drawing a plane. The possibilities of a flying object fascinate him. Planets, rockets, planes, he draws them all. In his box of crayons, the single steel grey colour is his favourite.

Appa is filling his pipe. He carefully separates strands of tobacco from the pouch, pressing them into the bowl. It is a skill he taught me as a child—neither too loose, nor too tight. He observes Sanju, a look of abstraction on his face.

Then he speaks, ‘You know, when Swami Vivekananda was a little boy, he liked to draw. His family would buy him water colours that cost some…four annas a box and he loved painting with them. He was very naughty as a child, probably naughtier than Sanju. So his mother complained to Shiva. She said to him, “I asked you for a son, but you sent me one of your ganas instead.”

Appa lights his pipe and extinguishes the match, waving it rapidly.

‘You see, she prayed to Vireshwar, Shiva, for a son and she also asked a relative in Benaras to worship the deity at the temple on her behalf every single Monday, for an entire year. Bhuvaneshwari Devi herself, the great woman that she was, fasted and prayed to him in Calcutta. One day, she dreamt that Shiva would grace her by himself becoming her child. She woke up with the sensation of being covered in light. And in time, she did have the son she desired. But then, Shiva has his own way of answering prayers. Take Markandeya for instance. His parents had to choose between a brilliant son who wouldn’t live long and a son of average intelligence blessed with a long life.’

‘Like Shankara,’ I add.

Appa laughs in agreement. ‘What a child Shiva gave her! Actually, he gave Bhuvaneshwari Devi not one but three sons. Vivekananda had two younger brothers. Now this child, her eldest son, he was naughty and full of energy, getting into all sorts of mischief. And he had a spirited mind as well. He would tease his two elder sisters, make them run after him and then leap across the open drain where the poor girls couldn’t follow. “Catch me!” he’d say. Or he would argue.’

I smile. It is a familiar situation. Appa draws on his pipe. The aroma of tobacco swirls around him. He settles deeper in his chair. ‘He had been taught not to use his left hand, you know, like all of us. One day while eating, he saw that it made sense to use the left hand to pick up the tumbler of water, since the fingers of the right hand were coated with food. So he argued about that and would not listen. Threats and punishment had no effect on him. Later, he said that one should never make a child fear something.

‘He was restless. How was this energy to be contained? Ultimately, after trying various methods, his mother found the only way of calming him down. She would pour cold water on his head, whispering “Shiva, Shiva” in his ear. It always worked.

‘In fact, when they wanted to name the child, they asked her to choose the name. So, she looked down at her baby, his life-breath the answer to her prayers, and she must have seen something in his eyes—a spark, an immense depth—something, for she was quiet for a while, lost in thought. Then she named him Vireshwar… They all called him Biley. Narendra was the name given to him later.’

I imagine her bringing up her son, but it is difficult to picture him without the robes and the turban. A little, rounded shape in a dhoti. I see a sturdy child whose face is all cheek, plump cheeks that compel one to pinch them, pull them, love him; thick black hair parted in the middle. Liquid mischievous eyes, of a shape divine. When he smiles, he reveals a gap, a fallen tooth. Merriment radiates from him as he climbs the forbidden champak tree or closes his eyes during a lesson. The thrill running through her when he repeats a shloka effortlessly, having heard it only once, or when he sits on her lap and puts his arms around her and asks why Hanuman has not appeared in front of him even though he waited for ages in the banana grove. In the next second, he is up and about, racing to his pet goat.

‘There was always apprehension in the family that he might take after his grandfather and renounce the world. Once, he wore a gerua kaupina, nothing else but that tiny piece of ochre loin-cloth, and went about the house saying, “I am Shiva, I am Shiva.” Think of what she must have felt and suffered when he did take sanyasa, renounced the world. There are only two people a sanyasi bows to. His guru, of course, and the other, his mother, for she gives him permission to take sanyasa.’

Appa points at the air with the curved stem of the pipe for emphasis, ‘It’s she who has to learn renunciation first.’

Bringing up a swami. A naughty swamiji: the thought engages me. Did she ever lose patience with him? Smack him on his cheek or bottom, and then regret it when he was grown, dressed in ochre?

‘He was an extraordinary man. He remained deeply attached to his mother to the very end. Normally, as you know, to become a sanyasi is to say that one’s former life has ended. That Narendranath Datta had died the day Swami Vivekananda was born. But not him. He was deeply concerned about his mother. That is the living Vedanta; that was what he was all about. Nowhere does it say that Vedanta and love of one’s mother do not go together, or, for that matter, love of ice-cream! Swami Vivekananda loved ice-cream. Chocolate ice-cream.’ Appa puffs happily on his pipe. To him, Vivekananda is a presence.

After a pause he continues, ‘A gentleman came looking for him once, in the hills of Almora. He knew him by the name Naren, and that is the name he used while asking for him. The boy at the door of the ashram, must have been a brahmachari, told him that there was no Naren Datta there. Narendranath had died a long time ago, but there was a Swami Vivekananda. He could meet him if he wished. Now Swami Vivekananda happened to hear this conversation and asked the boy, “What have you done?”

‘Then he asked for the guest to be shown in and when the guest called him Swamiji, naturally, after what had just happened, Vivekananda immediately responded with, “When did I become a ‘Swami’ to you? I am still the same Naren. The name by which the Master used to call me is a priceless treasure. Call me by that name.”’

My father transfers the beloved Peterson pipe to his hand, and I know he is enjoying the warmth of the bowl against his palm.

‘He was not one to be bound in any way,’ he continues, ‘least of all by notions of what it is to be a sanyasi. Towards the end of his life, he would say that he wanted to live in a small house by the Ganga with his mother, look after her, do seva. But that was not to be. Maybe with this thought in his mind, even at a time when his own health was poor, he took her on a pilgrimage to East Bengal and Assam. This was about a year before he died. He wrote a letter to Sarah Bull, his American mother, saying that he was trying to fulfil this wish of hers.’

I marvel as Appa quotes from memory. The words come alive in his rich, deep voice.

‘First Vivekananda announced, “I am going to take my mother on a pilgrimage.” Then he said, “This is the one great wish of a Hindu widow. I have brought only misery to my people all my life. I am trying to fulfil this one wish of hers.” Sometime after this, when his health deteriorated further— look at the problems he had, he suffered from diabetes and asthma; his one eye was damaged by a blood clot—he did not drink a single drop of water for two months as a cure. Around this time, his mother remembered a vow that she had made: as a child he had fallen very ill once, and it was so serious that his mother prayed to Kali. At that time she vowed that if he became better, she would send him to the temple to get darshan of Ma Kali. Somehow, it escaped her mind and the vow remained unfulfilled. Worried about his health, she asked Vivekananda to help complete that promise.

‘Obediently, He, the Swami, the great Shaamiji, Maharaj, as the Bengalis call him,’ Appa lifts his hands, miming adoration, ‘famous, and adored by thousands, he took a dip in the Adi Ganga, and even though he was sick, went the distance to the temple in wet clothes and prayed to Kali, just as his mother wanted him to. He was Swami Vivekananda but he was also her son.

‘He was truly concerned about her. When he went to the World Conference, there was another Bengali there: Mazoomdar from the Brahmo Samaj. Well, he saw how this young Bengali was adored by the audience, he became jealous of his success. When he came back to India, he spread beastly rumours, terrible lies, that Swami Vivekananda was immoral; that he was associating with white women. This of a man who attributed his many strengths to the power of chastity: his brahmacharya.

‘The Swami wrote a letter—I’ll find it in his collected letters and read it out to you—what he says is that it really does not matter to him what anyone should think of him. He is a sanyasi, a voice without a form as he once put it, but if his mother were to hear such things, it would cause her unimaginable pain.’ Perhaps without even intending to, Appa has located my fear, too overwhelming to be articulated, and soothed me in an indescribable way. Naren’s mother, she too had a child who was difficult to manage. She complained, to Shiva. But that did not diminish her love for her child. Neither did the complaint diminish her child. Look what he grew up to be!

Within me, an idea unfolds its wings; hope makes its way from her life to mine.

******

After working four long, dreary years in a multinational bank, Tulsi Badrinath quit her job to devote herself to dance and writing. Her poems, articles, reviews and short story have appeared in various newspapers and publications.From the age of eight, Tulsi learnt the classical dance-form Bharatanatyam, performed widely,; at events; has given solo performances in India, and abroad. Meeting Lives, which was on the 2007 Man Asian Literary Prize longlist is her first novel. Her second novel, Melting Love, was on the 2008 Man Asian Literary Prize longlist as well.

Leave a Reply