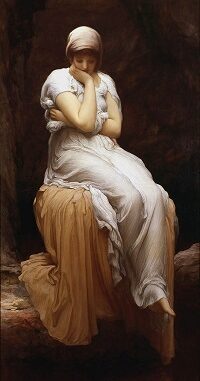

Frederick Leighton, 1890. Image source: maryhillmuseum.org

Romana Shaikh

I

t was in the early 2000s, I must have just turned a teenager. My grandmother had passed away and my family decided it was perhaps time for us to go our own ways. So plans were made for the joint family house to be sold and my immediate family of 5 started the hunt for a new home. My sisters and I had been going to a Convent school in Colaba (South Bombay), my mother was a lecturer at St. Xavier’s College and so the preference was to find a house that would allow us to continue with the same institutions.

We found a beautiful house that fit our budget, it was quaint and in a residential neighbourhood in Colaba itself. The house owner walked us out to the door, ‘Oh it was so lovely to meet you! Thank you. We look forward to continuing this discussion. What did you say your name was?’ ‘Rafiq, Rafiq Shaikh’ replied my father. ‘Oh, I’m so sorry.’ Bewildered, my parents inquired ‘Excuse me?’ ‘Muslims aren’t allowed here’.

Silence was all that followed. Silence.

In that moment, the silence was loud.

So loud, it broke something inside me.

In that moment, I became ‘the other’. The ‘bad other’. The ‘one-that-wasn’t-wanted’ other. The one that didn’t belong.

But why exactly didn’t I belong?

My 13 yr old mind didn’t understand how to make sense of this. ‘Is there something wrong with being a Muslim?’ I wondered. And if there is something wrong with being Muslim, then I don’t want to be ‘it’. I want to belong. And so began my first identity crisis. Which part of me is Muslim? How do I get rid of it? Is it the way I look? Is it the way I dress? Maybe it’s the way I talk? Do my friends think like this too? Can I actually trust them? What if they don’t want me to live next door to them as well? What if they don’t like me; or want to be friends with me?

What I didn’t realise then, is that the questions had made deep cracks in my just developing sense of self. Cracks that made way for shame; self-doubt and a-fear-of-never-belonging, to cement themselves into my mental make-up.

For years I carried not a question but a conclusion: There is something wrong with being a Muslim. It has been the conclusion I have lived with for most of my life and I still continue to struggle with it. Despite being in a cosmopolitan city of dreams – Bombay, with both parents working, coming from a social class that afforded me privileges of an English education, Western entertainment, a ‘liberal’ upbringing that made it possible for me to dress any way I wished, from shorts to skirts to dresses to jeans to kurtas and sarees, without a covered head–I still didn’t belong.

There was a growing ‘badness’ inside and it all seemed to centre on being a Muslim. And badness doesn’t feel nice. It feels like constant anxiety about being liked, it feels like depression about not being good enough. It feels like panic attacks when you need to write your name somewhere. It feels like going into hyper-vigilance when you walk into buildings and residential complexes that have rejected you and hyper-anxiety others might follow suit.

So began a new way of life – ‘Reject my-self’ Something is fundamentally bad about me.’

So how does one stop being a Muslim? You take all that comes with this identity, wrap it under layers and layers of shame and hide it. Then you take everything that is opposite to being a Muslim and you adopt it! Simple! I became a hyper-achieving, liberally-educated, modernly-dressed, highly-ambitious young, go-getting woman. And it worked!

Or did it? From a sympathetic, almost apologetic ‘Ohh you’re a Muslim.. Sorry’; I started getting, ‘But you don’t look like a Muslim!’ ‘But your English is so good!’ ‘Really? But you aren’t really a religious Muslim right?’ ‘Oh but you’re not like those Muslims.’

So no, I guess it didn’t work. I was stuck being a Muslim and I was stuck being ‘the other’.

This shadow of being a ‘Shaikh’ stuck to me and I continued to fight hard to get rid of it. While I never learned how to respond to the comments, I got better at pretending not to hear them. From 13 years old to 21 years old on to 35 years old and counting. My family and I have moved close to a dozen houses now, lived in various parts of Mumbai. The city has expanded its limits and connected the suburbs with the old parts of town. Buildings have grown taller, the night curfew has gotten tighter. Much has changed in this city I grew up in. And some things have remained the same.

So we learned to play the game – Now when we search for a house, the first conversation we have with the broker goes something like this – ‘So, we’re Shaikh. Yes, we’re Muslim. Yes, we know we don’t look like it. Will you still show us houses?’ Some brokers say no and the conversation ends at this point. Some feel awkward and say yes, but never return our calls. And then there are those that say ‘Oh yes, I don’t have a problem but it’s the owners you see.’ And so we continue with these few, ‘Now you make sure you only show us houses that we can actually live in.’ We feel satisfied that we’ve made ‘them’ feel awkward and proud that we’ve claimed our identity.

But have we really? Have we been able to welcome ‘others’ to share in our culture and our practices? Have we gone beyond the awkward smiles, bad jokes and ‘I love biryani’ professed to every Muslim? Have we spoken our truth about what it feels like to be a minority? Have we shared how painful, disheartening and soul crushing this experience of feeling like the ‘other’ is to live with?

A Game of Denial

When rejecting our Muslim-ness wasn’t an option, the next level of the game we had mastered was one of denial. There wasn’t anything to share if we didn’t acknowledge there was a problem to begin with! So ‘normalizing’ our experiences was the only way we knew to survive an increasingly rancid environment – Deny and reject.

Be it the floods and earthquakes or wars and economic depression, the loss of life in the pandemic and the increased poverty and oppression of marginalised communities. The world is becoming a scary and unsafe place.

As I work with children and communities, teachers and education systems around the world, I have found more and more players of this game of denial snd rejection. I’ve come to understand it as a first line of defense that protects those vulnerable parts of our identities. While the stories are different, the labels we call ourselves are different, this raw feeling of being ‘the other;’ the ‘bad other’ The ‘one-that-wasn’t-wanted’ Other: the one that didn’t belong… is actually a far more common human experience than we let each other acknowledge or recognize. I’ve met it in the anger that our female bodies carry, the shame that our marginalised bodies carry, the fear that our childhood bodies carry, the guilt that our privilege carries.

Meeting (an)other?

I feel it in my Muslim-ness. I also feel it in my Brown-ness and my Woman-ness. With English vocabulary, an Uber pick up a swipe away and my credit cards, I’m protected or rather I have the privilege to disconnect from some of the pain of my fellow human beings. But how far will this denial and rejection of the truth of our human existence today really get me? Where will it get us? I wonder as I continue to unpack my identities that have afforded me privilege and subjected me to oppression.

What will be ‘me’ if I look under these labels, these categories of being an Indian Muslim Woman, the-one-that-doesn’t-belong-other? If I can go beneath the labels, the traits, the stories that separate me from others, if we can go beyond them, go behind them, get ahead of them, get under them – what we’ll maybe…just maybe…find, is the felt sense of the experiences, the feelings, the values that connect us.

That human need for connection, for belonging, for love that is underneath all our fear and hatred and othering.

That place where the silence is not loud. Where the stillness doesn’t separate. That place, is beautiful, uplifting and peaceful. For me and for you.

******

Romana Shaikh is the Chief Program Officer at Kizazi, a global non-profit that seeks to catalyze innovation in the design of school models to enable all children to thrive. She has deep experience working across India, West Africa and Armenia with local teams to transform public education to so education is contextually responsive, restorative of culture and identity & relevant to the needs of young people and their communities. She practices Presence Oriented Psychotherapy with individuals and groups and is currently involved in collaborative and peace building efforts for the Indian Muslim community. Through her work, Romana is studying the relationship between personal transformation and systemic transformation. She is a faculty member for Comprehensive Sexuality Education, Presence Oriented Psychotherapy. A Salzburg Global Seminar Fellow and an alumnus of Teach For India. Previously, she has been the Director of Training & Impact for Teach For India & a consultant to TFIx, TFAll and various other NGOs in rural & urban India. Romana loves tending to plants, practicing yoga and meditation and learning from various wisdom traditions. She enjoys learning about cultures and the diversity of life experiences people have through reading and traveling & being a part of communities.

I feel mortified after reading Romana’s “story” and ask myself why I should I be living in a country that doesn’t know how to take care of its citizens’ basic rights and feelings. The hurt is simply unbearable!