Insurgency: The Art of the Freedom Struggle in India and The Artist. Vinay Lal. Lustre Press, Roli Books, 2022. 260 pages

Pooja Sancheti

Introduction

A

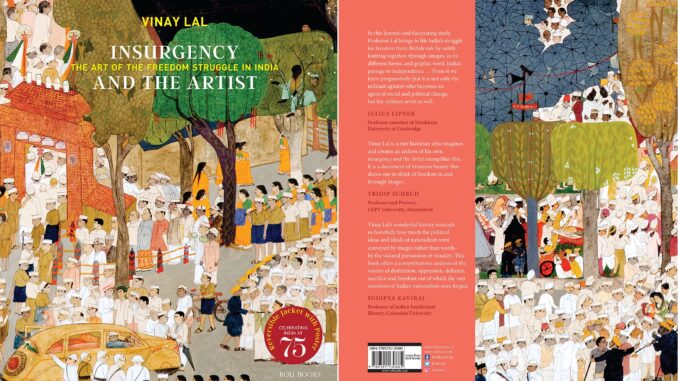

nation’s 75th anniversary of independence naturally presents itself as a significant moment to look back and examine the journey of becoming, for in looking back, we may perhaps understand our present better. Vinay Lal’s weighty tome is such a step back in time to modern India’s most tumultuous moments during its freedom struggle from 1857 to 1948. Through this volume that combines reproduced artwork, its interpretation, and a historiography of this period within the palimpsestic framing of the past and the present, Lal offers insights into how the political and cultural imaginations of the various phases of ‘insurgency’ were shaped and fuelled by the artistic output of the time. Art here does not indicate rarefied pieces hanging in hallowed galleries but a mix of what he calls “bazaar” art that includes pamphlets, calendars, popular prints, some newspaper cartoons, collages, as well as sketches, water colours, oils, and lithographs. Photographs are largely absent from the catalogue.

For the most part, “Insurgency…” is not a book about artists’ lives and the inner workings of publishing houses; it is a book about nationalist leaders and the many facets of anti-colonial struggle, and how their representation in art is vital to their location in their context and our interpretation of political history.

The book is split into eleven chapters and four boxes, and the order is chronological; either a major event or a key political figure is treated as the central theme of each chapter. However, like all lively history writing, seldom does a chapter focus solely on its declared theme. Rather, the narrative accommodates vignettes, tangents, and distractions that add to the particular in enriching and sometimes delightfully surprising ways (like the appearance of a Professor McSweenie!)

*

The frontispiece displays several tropes that occur time and again in Lal’s archive of art present in the book. Subhas Chandra Bose in his martial uniform is offering his head as sacrifice to Durga/Bharat Mata as other slain leaders’ heads lie around him. Krishna blesses the scene, and an eternal Bose wearing Khadi holds the Indian flag in the background. The reader will come across the imagery of sacrifice, the conflation of Hindu mythology and political leaders, the worshipful attitude towards the icon of Bharat Mata/Mother India, and nascent state symbols like the flag several times through these pages. The other prominent arc of the book is captured in the first print of Chapter I: an oil on canvas (late 1940s) by Kamal Ray depicting Gandhi walking in Noakhali. Once Gandhi becomes associated with the Indian political scene, he looms large in the book’s images and narrative.

Chapter I lays out the theoretical and introductory background of the work, including tools offered by Erving Goffman and John Berger to read images, and Christopher Pinney’s work on India’s historical visual art that Lal often is at odds with. The primary impetus of the book, Lal states, was to understand “how had artists in India responded to the anti-colonial movement” (10). While the book does not dwell on artists’ biographies, the introduction lays out the importance of several larger cities and their printing presses, especially Kanpur (Cawnpore). Shyam Sundar Lal’s press in Kanpur features prominently throughout the book and serves as an instance of how artists and publishing houses dealt with nationalism, censorship, and copyright. Lal also bemoans the lack of adequate archival practices and the ensuing loss of much artwork that would have captured key events like the Jalianwala Bagh massacre. Art lost to time speaks volumes about larger matters of politics, economy, artistic value, and mechanisation.

The author also mentions how the Bhakti movement, by some accounts the true antecedent of syncretic “Indian unity” was, in fact, retrospectively imagined as a unified pantheon of saints only in the wake of the nationalist struggle. The apolitical, thereby, was co-opted into the political, however covertly.

Chapter II focuses on the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857-58; the opening print of a certain Miss Wheeler fiercely defending herself from violent Indian sepoys exemplifies the projected narrative of victimhood by the British, which brazenly hyperbolized vicious sepoys attacking hapless European women and children. Lal is careful to state that the Mutiny is only a convenient starting point for the anti-colonial struggle and not the definitive one, since the preceding decades were rife with famines, epidemics, and much unrest in the countryside. All the same, it effectively shifted governance from Company to Crown. V D Savarkar’s interpretation and his deployment of artistic recreations of the Mutiny feature heavily in the chapter. Several prominent figures like Bahadur Shah Zafar, Nana Saheb, Brigadier General John Nicolson, and Sir Arthur Cotton feature in text and visual narratives produced from Indian and British perspectives.

Box A is a collection of the iconography of Rani Lakshmibai of Jhansi, who is a popular figure even in current nationalist art. Lakshmibai was and remains, in the words of Sumathi Ramaswamy, the sole “big” woman in a pantheon of “pictoral big men” of Indian nationalism (32). Chitrashala Press and L Pednekar Publications of Bombay are sources of much of the artwork on the martial-maternal queen.

Bal Gangadhar Tilak and his contemporaries, his role in the Indian National Congress (INC), his (and others’) demands for self-governance through channels like the ICS, and his calls for mass Hindu festivals feature in Chapter III. M V Dhurandhar’s water colour portrait of Tilak portrays his resolve and his caste markers.

Crucially, Lal traces artists’ retrospective invocation of Chhatrapati Shivaji, Maharana Pratap, Prithviraj Chauhan, and King Hemu (all Hindu kings) to create and solidify a militant and masculine (Hindu) nationalism that created itself in the mythico-historical shadow of this invented indigenous tradition.

Apposite to the tradition was the rising visibility of warrior goddesses like Durga/Bhavani, who eventually transform into Bharat Mata. A print of RSS founders K R Hedgewar and M S Golwalkar from this period encapsulates the role they envisaged for their organisation in this tradition; Lal also remarks on their fascination with Nazism.

He points out that the militant Hindu nationalist tradition eventually began to include openly secular figures like Bhagat Singh and Subhas Chandra Bose, and even the non-violent Gandhi. He uses a remarkable calendar art print, likely from the mid-1940s, to instantiate how artists could easily place figures from different times and ideologies alongside each other (Gandhi, Bose, Chandrashekhar Azad, Bhagat Singh, Shivaji, Pratap, and Lakshmibai), and call them “Bharat ke Veer”, all equivalently Indian.

Chapter IV is the longest chapter and herein begins Gandhi’s large presence in the nationalist movement and in the book. Gandhi’s representation is inextricably intertwined with Hindu religious symbolism and mythology, as per the images collated here and their interpretations. Gandhi is variously represented/labelled as a ‘devata’, a ‘prophet’, and as a modern-day avatar of the Buddha, Krishna, and Rama. Lal reads this as the artists’ reliance on known religious tropes to make sense of a massively tumultuous present. He emphasizes Gandhi’s overshadowing all other prominent leaders of from the1920s- late1940s. His trademark dhoti, glasses, charkha, and walking stick lend themselves to iconic artistic representations as well, which Lal remarks, are unique to Gandhi. These symbols mark a departure from the militant masculine nationalism of the past decade. The chapter dwells on Gandhi’s political and personal philosophy (swaraj, satyagraha, ahimsa), his lifestyle, and the Indian public’s faith in him, which is captured not only in the numerous artwork samples produced then but also the divinity attributed to him through the artwork. Artists Prabhu Dayal, D Banerjee, and presses from Kanpur, Lahore, Karachi, and Bombay feature prominently.

Lal comments on but does not explain the paucity—though not absence—of Kasturba’s representation in art. In one print that he analyses by Roop Kishore Kapur, Kasturba is labelled ‘Mateshwari’, a synonym of Parvati, which makes Gandhi Shiva, albeit through linguistic rather than visual symbolism.

Chapter V revolves around the Salt Satyagraha, an important public movement by Gandhi. Given the prominence of the event, artwork on it abounds. Nandlal Bose’s linocut of Gandhi on the march to Dandi is stunning in its simplicity, as much as Ramendranath Chakraborty’s painting. Lal adds to the Dandi March simultaneous events that were unfolding in British and Indian socio-politics, including the Noakhali riots. While cartoons are sparsely referred to elsewhere, this chapter contains some from foreign newspapers and magazines on Gandhi. The role of women like Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay and Sarojini Naidu in breaking the salt law, and the violence meted on Indians in the wake of this ‘illegality’ are poignantly captured in artistic representation.

Box B is a collection of Gandhi’s representation in the work of artists like Kanu Desai, P S Ramachandra Rao, Dhiren Gandhi, the Chore Bagan Art Studio (Calcutta), Lakshminarayan Sharma’s Nathadwara style paintings, Hemchandra Bhargava (Delhi), and touches upon the writings of work of Rabindranath Tagore and Mahadev Desai, and the historian Shahid Ali. The genre of biographical print or jivani, that uses stages of an eminent person’s life, was frequently deployed for Gandhi, as it was for Krishna, Rama, and the Buddha. Artwork analysis also includes the language(s) used for labelling and titling.

Chapter VI focuses on the specifics of the political oppression and economic ruination of India under colonial rule; Roop Kishore Kapur’s ‘Sampatti Haran’ is an excellent example of the exact points of exploitation and personifies India and Britain as victim and oppressor respectively. The satire magazine Avadh Punch 1891-93 cited here would be excellent further reading. Dadabhai Naoroji’s and R C Dutt’s writings and activism add to the economic narrative of the nation. The star remains Gandhi, whose views on economics, governance, and even advocacy for prohibition (exemplified through a clever adaptation of the Putana-Krishna episode) are given centre stage.

A welcome tangent is a brief biography of the artist Chittaprosad Bhattacharya (1915-78), whose work closely captured not only Gandhi’s role in the anti-colonial movement but also the Partition, the Left’s struggle for workers and farmers and the like.

Chittaprosad’s stark black and white sketches of people suffering during the Bengal famine of 1943 are heart-wrenching and powerful. The role of the People’s War, a newspaper run by the Communist Party of India is highlighted here. Another equally important artist mentioned is Zainul Abedin (1914-76) of now-Bangladesh, whose despairing images of similar suffering illustrate that the anti-colonial struggle was hardly a story of one political victory to the next.

Chapter VII explores Bhagat Singh’s primacy in popular imagination and the re-centralization of militant or armed nationalism that was openly juxtaposed to Gandhi’s call for non-violence. Lal argues that in spite of Bhagat Singh’s popularity, the artwork of the time does not exemplify this: “The turbaned Bhagat Singh is also a comparatively recent invention, one perhaps prompted by more militant calls for the affirmation of a distinct Sikh identity…In his own days, the most widely circulated photograph of Bhagat Singh, which in turn would inform the vast majority of nationalist prints where he was featured, shows a clean-shaven, mustachioed man staring unflinchingly into the camera and sporting a trilby that is sometimes identified as a fedora” (130-31).

The trilby of the 1920s is replaced by the turban now, which, Lal indicates, is how the index of political moods can be detected by subtle changes in iconography.

The chapter also delineates the formation of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association by Chandrashekhar Azad and Bhagat Singh (among others). Jatindra Nath and Bhagat Singh went on hunger strikes, encapsulated in prints by Roop Kishore Kapur (published by Shyam Sundar Lal, Kanpur). Bhagat Singh’s contemporaries, Khudiram Bose, Rajguru, Sukhdev, and others also feature here. What enriches the narrative are relatively forgotten incidents that the author brings in that prominent narratives leave out but the artists of the time had thought significant enough to be captured. The chapter returns again to Gandhi; an important confluence between Bhagat Singh and Gandhi, despite their different approaches to the anti-colonial struggle, is represented through images like Prabhu Dayal’s ‘Swatantrata Ki Vedi Par Viron Ka Balidan’ (1931).

Chapter VIII is a broad discussion of Hindu mythography from sources like the Ramayana, Mahabharata, and the Puranas, as well as Buddhist and Jain art, and its deployment in anti-colonial artwork. Themes like ascension to heaven (especially of Gandhi), sacrifice, Hindu goddesses recast as the nation goddess, and dharma chakras, are prominent. The chapter picks up from Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay’s views on Krishna and Hinduism, and the increasing importance of the Gita among the freedom fighters of this period. As showcased in the artwork, the battle between Rama and Ravana easily lent itself to representing good versus evil, which was both the colonial government and rising communalism.

Box C continues with the theme but more narrowly focuses on the iconography of Bharat Mata or Mother India. Antecedents include warrior goddesses, Durga and Mahishasuramardini, and Earth goddesses of tribal mythologies, but also the mendicant by Abanindranath Tagore. The figure was humanized by portraying her as helpful, sorrowful, and benign in different contexts. Lal discusses Mother India’s role in the politico-religious framework in art and literature (like ‘Vande Mataram’). The figure also becomes conflated with the Indian flag (in its various versions) and Indian cartography. Lal points out how using mythological imagery provided artists protection from governmental penalties by couching their political dissent in legitimate ‘religious’ art.

Chapter IX revolves around the consolidation of the INC, Subhas Chandra Bose, and the motif of sacrifice. Like Gandhi, Bose also seems to have captured artists’ imagination, and several biographical prints of his life or jivanis were in circulation. Key events like the Tripura Congress meet, meeting Hitler, and the Azad Hind Fauj, as well as his representation as a military statesman are prominent in the art about him in this period. Bose is ideologically both aligned with and juxtaposed to Gandhi, and this argument finds confirmation in artistic representations.

A wonderful sketch of Birsa Munda by Upendra Maharathi in 1940 shows his prominence in the nationalistic imagination of the time. The inclusion of relatively less discussed but nevertheless important figures like Ganesh Shankar Vidyarthi indicate how incomplete histories are when we focus only on a handful of figures, events, and dates. In terms of available artwork, the period, given its temporal proximity, is rich. Cartoons and caricature are highlighted, and artists like Gogonendranath Tagore and the historian Mushirul Hasan will be interesting to anyone wishing to explore this genre further.

Vinay Lal in The Beacon

Chapter X moves to the last few years of official British rule on India, circa 1942-1947. The chapter opens with a painting of Khan Abdul Gaffar Khan, and discusses Frontier Gandhi’s role in bringing the geographical margins to the fore. Lal lays out in some detail the messiness of the idea of purna swaraj, the many interpretations then and now of what political freedom meant/means, and the Partition of 1947 that mars any pristine victory that might have been imagined. Gandhi’s and the Congress leaders’ roles, as well as Jinnah’s rise are discussed. Lal is careful not to conflate Muslims with the Muslim League, a distinction that is all the more significant today. Artwork documenting the Quit India movement is rich; Babuji Shilpi’s impressive gouache is also the cover of the book. Beohar Rammanohar Sinha, the artist whose work adorns the first edition of the Indian constitution, Qamarul Hassan’s wood blocks, Chittoprasad’s brush, ink, and gouache, and Sudhir Chowdhury’s paintings capture the more- and less-recalled uprisings of the time. The artist Somnath Hore gets some biographical space here.

Box D is M. Thimmiah Sresty’s chromolithograph titled “Kalpataru: The Freedom Tree” (1946), which, like its mythological template, is a wish-fulfilling tree that underlines the importance of the INC in the 1920-1940s. It is available as the folded-in jacket poster. Gandhi at the centre of sprawling tree reflects how ahistorical mythological symbolism is always at hand to shape current political and cultural imagination. The obvious Hinduisation of Gandhi while being surrounded by prominent and lesser-known leaders, educators, lawyers, economists, and writers from all religious backgrounds, men and women (including Kasturba), and the linguistic material in Sanskrit, Hindi, English, and Tamil create an image rich for interpretation. The notable omission of Ambedkar in this poster can be explained through his non-association with the INC.

The final chapter is titled ‘Free but Partitioned: Independence, Gandhi’s assassination, and the Future of India’. Gandhi’s assassination, or ‘shahadat’ (martyrdom) forms the endpoint of this book’s narrative. The opening print of the final chapter is Sudhir Chowdhury’s image of Gandhi in the lap of Mother India with Pieta-like resonances. Photos, though plentiful at this time, are justifiably not a part of the book. Artists’ representation of the violence that was rife in these years is highlighted instead, and the works of Chittoprasad, Krishan Khanna, Ratan Parimoo, Prabhu Dayal, K R Ketkar, Narayan Sharma, and others provide the reader with a substantial sense of artists’ engagement with this painful period. Equally, artists seemed invested in projecting that the leaders who succeeded Gandhi would be capable enough to steer India towards its promised future. However, the book ends with the especially heart-rending works of S L Parasher, Paritosh Sen, and Upendra Maharathi, which capture the fresh wounds of partition violence and invite the reader to examine our precarious present.

Lal’s comment on the anguished figure in Parasher’s ‘Cry’ (1947-48) sums up the despair of the moment: “His cry was the cry of tens of thousands, indeed of millions; the world had been turned upside down, and momentarily at least many had gone mad. India had become free and the next generation of artists would have to wrestle with the meaning of this freedom” (245).

*

“Insurgency…” will appeal to the specialist who will find the author’s inclusions of and departures from other historians like Pinney, Ramaswamy, Partha Mitter, Sugata Bose and others, the resultant archive of art, and the closing pages with references and further reading extremely helpful. The book is equally appealing to the generalist, since the writing style is not dense and the anchoring points are well-known events and figures.

A minor irritant is that images and their explanation often do not align on the page, compelling the reader to go back and forth. Perhaps readers could take advantage of this mismatch, and take the layout as an invitation to examine and interpret for themselves the images the text presents without the aid of the author’s interpretation. It is quite possible to find some departures between authorial and readerly interpretations, circumscribed as they are by the material available on the page.

A more serious concern arises with this material that is made available to us through the framework of the historical narrative and the book. The most circumspect of historians are faithful only to the archive or remnants that are available to them. A wise reader of history is similarly bound. A discernible thread runs through the artwork available in the book, and it is of the primacy, if not monopoly, of Hindu symbolism and mythology in nationalistic art. At any other time, this might not have been a concern, and like the Indian artists of the 1930s, we could have easily imagined this to be only one among many threads in the fabric of nationalism.

However, given the current socio-political trends in the country and the world, I wonder if history would have been served better either by offering a disclaimer about the limitedness of this (as any) archive, or by being deliberately more inclusive and syncretic.

I am not an art historian, but the book does make me wonder about what is present by its absence, and what might have been other ways of imagining the nation that do not find purchase here. Lal does not shy away from critiquing the rise of right-wing nationalism in India, nor does he overlook the overzealous adoption and adaptation of icons sans any genuine desire to understand the icons’ motivations and ideologies. This begs the question: how is the cause of the critique served by providing material that almost exclusively upholds a Hindu imagination of India?

One figure that Lal has entirely omitted in his-story is B R Ambedkar. In the introduction, he recognizes this omission, and points to Ambedkar’s necessitated inclusion in any and all stories of India: “These days it is a political and personal liability if Ambedkar is not brought into a conversation having to do with ‘the political struggle’ in late colonial India” (19). He touches upon Ambedkar’s role in the consolidation of the Republic, and his absolute importance to Dalit and justice movements. He justifies Ambedkar’s absence by stating that “the popular iconography of Ambedkar only begins to develop in the 1960s, slowing evolving after his death in 1956”, a time period that is outside his current consideration. Besides, Ambedkar was opposed to Gandhi, and “cannot…be viewed as having taken part in the anti-colonial struggle” (16).

Opposed to Gandhi’s ideology was another stalwart, Subhas Chandra Bose. Lal’s interpretation of Bose, his ideology, and even artists’ representations of him seems unduly harsh in places. For no other figure does Lal insinuate that the artists obliged the personal whims of the subject and propagated a certain iconography. For Bose, Lal writes:

“Not only did he (Bose) practically have himself anointed a general and a commander-in-chief of what would be termed the Indian National Army, as printmakers obliged with portraits of Bose in military regalia, but he availed of the European tradition of equestrian poses to have himself rendered as a heroic figure of military valour, poise, and grace” (174; emphasis added).

Finally, the “militant artist” unfortunately remains, for the most part, represented only through his (there are no women artists) art. Unlike the nation’s more well-known freedom fighters, the artists’ biographies and their milieu are missing, which is perhaps a result of a paucity of archival resources to begin with.

A wise reader would approach history with a measure of caution and awareness of their own ideological framing. An archive, however extensive, is never complete or definitive. Vinay Lal’s new publication is a visual delight and an invigorating look at how dynamic history is, and how political imagination, historical sources, and national narratives can be constantly reread and reinterpreted from the ever-present lens of our own contexts. More such well-rendered volumes will add to the corpus of both art and national histories.

******

Dr Pooja Sancheti is an Assistant Professor in the Humanities and Social Sciences Department at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER) Pune, India. Her current academic interests are South Asian Anglophone fiction, transnational literature, women’s writing, magical realism, and postcolonial theory. She is also an amateur Hindi-English translator. She also dabbles in the interdisciplinary domain of language and science and teaches EAP, a parallel research interest.

Pooja Sancheti in The Beacon

Leave a Reply