Courtesy: Avijit Roy/.thebetterindia.com

Paradox: a person or thing that combines contradictory features or qualities (Oxford Languages Dictionary)

*

‘Oh, did this blasted rain have to fall now only!’ Ramadeen grumbled as he wrapped a torn quilt around his body.

‘Chee! You’re a farmer. How can you curse the rains!’ Baliya immediately scolded him.

‘Farmer, bah! For the rest of my life, I have to burn my flesh and bones in this masin. If it rains all night, there will be a river flowing under this thatch. Get it?’

‘Yes, but-, farms and fields will get water, no!’

‘As if the blasted fields are yours! Here I am, feeling sick, now this rain, and on top of that, tomorrow Chaarman Saab is arriving.’

‘Who is this Chaarman Sa-?’

‘The owner of masin, who else?’

‘Masin also has owner?’

‘No, no, it falls straight from the sky!’

‘He’ll really come when it is pouring?’

‘So? He doesn’t have to walk on his own two feet. He’ll come, sitting in a boat or car.’

‘And what’s that to you?’

‘If the fever goes up, how will I go to masin?’

‘Then don’t go. As if Chaarman Saab is coming to meet you!’

‘Oh, you dull-brained woman! If I take leave, won’t I lose my wages?’

‘Ram Ram!’ Baliya said in an anguished voice. ‘May God stop the rain. This thatch is already dripping!’

But the rains did not stop.

It seemed as if the rains this year were Indra Dev’s atonement for his past mistakes. It felt less like rain, more like lashes. Fields and grounds, rivers and streams filled up, but so did roads, potholes and huts. Belapur is not a village, where water gets absorbed by the earth and bursts out as grain. It is not a village but it is not a city either, with pukka roads. It is an industrial town. A wafer-sized town in the rustic countryside, in an age punctuated by industrialization. And so, the Belapur Cement Factory’s building is pukka, the officers’ houses are pukka, and the road between the factory building and the officers’ houses is pukka. Inside this concrete building, the machines are modern, and in the bid to become ever-more productive, are becoming ever-more technologically advanced. But outside the factory, apart from the fields and farms, there are unpaved roads and open gutters surrounding the shacks and mud walls of the basti where people, forced by mechanization, live as daily-wage labourers.

The rain did not cease all night, causing the dirty water of the gutter to flow into the huts, where it mixed with the clean water dripping from the thatched roofs, and then flew out with double the force.

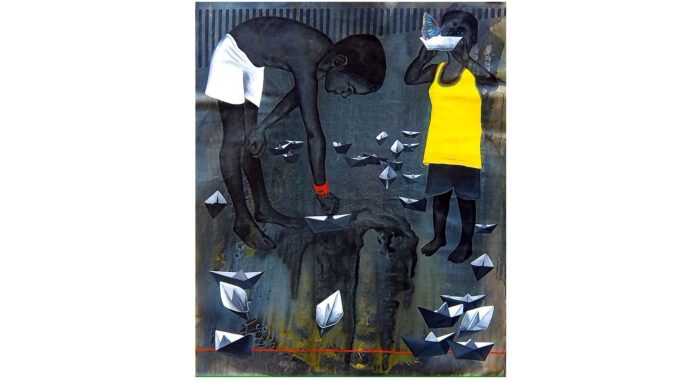

Until 3:00 am, the residents of these huts, wrapped in their torn quilts and blankets, tried to find some dry spot under their huts’ flimsy coverings that masqueraded as roofs. At 4:00 pm, they gave up on this futile effort. The men, holding on to their damp quilts-blankets, headed to the factory. It was easy to find dry corners to sit there. The women remained occupied in a futile attempt to separate their less wet belongings from their more wet belongings and move things from one end to the other, up to down, to try and salvage what they could. Once they saw it was dawn, the children came out from under the thatches and, surrendering fully to the rains, started floating tiny boats made with garbage in the dirty gutters.

Ramadeen, shivering from intolerable fever and cold, tried but could not muster the energy to join the other men to find shelter at the factory. He lay moaning and groaning in one corner, on a wooden box atop an upturned stove, wrapped in all the sheets and quilts they possessed.

‘Try and go to the factory. Compounder Babu may give you some medicine,’ Baliya kept repeating.

‘See, the rain is slowing down now’, she said again, ‘who knows, the sun may come out!’

But something even more unexpected than the sun’s appearance occurred. Baliya stared in amazement at the sight: along with a whole group, Manager Sahib was approaching, holding an umbrella, not on his own head but covering someone else’s head.

‘Hai daiya! Look, look…Manager Saab!’ she urgently whispered to Ramadeen, who shook his head and opened his eyes.

‘Chaarman Saab,’ he rasped.

‘What?’ Baliya asked.

‘That…that…Chaarman Saab,’ Ramadeen wriggled out and in one leap, was out of the hut. Delirious with fever, he assumed that Chairman Sahib had found him playing hooky and come to arrest him.

Chairman Sahib was walking towards the huts and stopped where the children were floating boats made with garbage. People watched as he shook his hand and said something to Manager Sahib, said a lot, and Manager Sahib listened with his head bowed. What exactly he said was not audible to those around, since they were out of earshot. But they could figure out that Chairman Sahib was upset. Whether he was upset with Manager Sahib or with them was harder to figure out. No one knows what went through the minds of the dull-brained women, but Ramadeen, hiding behind the hut, lost all hope. He thought, this time it wasn’t going to be just sieving but complete uprooting. He looked again and saw Manager Sahib standing on a stone and announcing something.

‘Workers of the Belapur Cement Company,’ he was saying, ‘our Chairman Sahib, our godlike Chairman Sahib has seen these hardships caused to you because of the rain, and has decided to heave the burden of helping you. This evening, food and blankets will be distributed to you all at the Welfare Office of the factory…’

‘No, now!’ Chairman Sahib angrily interrupted him, so he repeated himself, ‘Now, in the next two hours, all of you gather at the Welfare Office. Everyone will be given ration and blankets…yes Sir, I am telling, …children will also get milk.’

Chairman Sahib rebuked him: ‘Tell them everything I said,’ but Manager Sahib tried to dissuade him, ‘It would not be right to say it here, Sir, not now.’

By this time, the workers at the factory had heard the news and come running to the basti. Chairman Sahib glanced at the growing crowd and stood up to make the announcement himself in a loud but shaky voice.

‘Workers of Belapur Cement Factory, your troubles will soon be erased. By Diwali, the pukka houses of the Workers’ Colony will be ready. You will all celebrate Diwali this year in your new homes!’

Over the thunder of clapping, chants praising him rose, and people watched, surprised, that tears were flowing down Chairman Sahib’s cheeks.

‘Chairman Saab ki jai! Chairman Saab ki jai!’ Ramadeen was sloganeering and ran towards Chairman Sahib and collapsed right at his feet. Before he could understand what had just occurred, ‘Hai daiya…save him!’ Baliya screamed and fell on Ramadeen and began to wail, ‘He has fainted. Save him, don’t make me a widow, think of the child in my stomach.’

‘Is he sick?’ asked the Chairman, annoyed.

‘Yes Saab, he fainted! Fainted!’ a terrified Baliya kept repeating. Chairman Sahib turned to Manager Sahib, and instantly, two men came forward and picked up Ramadeen, a third admonished Baliya: ‘Stop, don’t cry. Come to the hospital.’

‘Yes, take him urgently to the hospital,’ Chairman Sahib said.

‘God bless you! May you live long!’ Baliya wept as she fell on Chairman Sahib’s feet. He sprang back and nearly screamed, ‘Go, go! Take him quickly!’

When the chairman of Belapur Cement Company, Subodh Kumar, had landed at the Benares airport, it was pouring cats and dogs. Despite his umbrella, he was drenched by the time he walked from the plane to the airport building. But he was not in the least bothered by the spots appearing on his expensive suit or the squelching in his expensive shoes. He closed the umbrella and lifted his head and found Prabha standing in front of him. No one else had come. Finally, his staff had understood that he really did not want any of them to receive him in Benares. But yes, arranging for Prabha to fly from Bombay to Benares to greet him was pleasing to him.

‘Hello,’ he called out happily. ‘Fantastic weather.’

‘Fantastic?’ Prabha said in a surprised note, ‘You weren’t satisfied with the amount of rain in Calcutta?’

‘Rains in Calcutta are not the same as the rains in Benares, Prabha! In the hustle-bustle of Calcutta, even the rain seems artificial, makes one more anxious, not less. But here…here is openness, comfort…’

‘All this is probably poetic stuff, I may not understand it,’ Prabha huffed, ‘but Benares has no less hustle-bustle. Go to the city and see.’

‘Maybe. But the Benares I know is filled with nature, beauty, peace…and you.’ Subodh Kumar put an end to the discussion.

Prabha heard the affection in his voice so she made-believe offence. ‘Really, it is quite a shitty city. I’ve been here since yesterday, and not one place worth going to.’

‘Find places worth going to in Delhi,’ he replied harshly.

‘Will you come with me to Delhi?’

‘We’ll see.’

Prabha glanced at his face and figured out he was upset.

‘Carlton is a lovely hotel,’ she said immediately, ‘…has a beautiful garden. You’ll like it.’

‘I don’t understand what you people love about the glitz and glamour of Delhi-Bombay. It’s just the fake shine of money. I detest it. I can’t sleep for nights. Life is in these small cities, in natural beauty. I wish I could make a small hut and live in it, eat simple food, and sleep restfully.’

Prabha stopped herself from telling him that one needs money even to build a small air-conditioned hut surrounded by a large garden. She knows that he does not like arguments. He is quick-tempered. And his anger has never proved beneficial to her.

*

Subodh Kumar woke up early the next morning. After a long time, he had been able to sleep deeply. He rang the bell for tea and drew the curtains. He looked out the window and remarked, ‘Arre see, it is still raining!’

When there was no response, he turned around and saw Prabha was still fast asleep.

‘Prabha, Prabha!’ he shouted. Once he was up, he could not abide anyone else still sleeping.

Prabha squirmed and opened her eyes.

‘Arre, get up!’ Subodh Kumar said, ‘See, it’s still raining!’

He opened the windows and remarked, ‘See how lovely the garden looks!’

‘Okay, tell me something. You come here so often. Why don’t you get a bungalow made for yourself here?’ Prabha came up to him.

‘This is better. If I stay at home, there will always be a crowd. Servants, family, friends. I have enough of that sycophancy in Calcutta. When I stay here in a hotel, it’s like everyone else. No one knows me here. No one sees me here.’

Prabha decided not to prolong this conversation. She knew this was one of his carefully crafted illusions and there was no point debating over it. After all, she did not have the rights of a lawfully wedded wife.

‘Do you plan to go to the factory?’ she asked.

‘Of course. I have asked for the plane at 8.’

‘In this much rain?’

‘Eh?’ Subodh Kumar thought for a bit, then replied: ‘Maybe not. The airstrip there is kachcha. Okay, I’ll go by car.’

‘It’s a tiny little place, Belapur?’ Prabha commented.

‘It’s an excellent place. Beauty all around. And peace. Would’ve been great if you could’ve come along.’

‘Shall I?’ Prabha asked.

‘Maybe some other time…’

She knows he may say this but he will never take his mistress to his ancestral factory.

‘I really like it there,’ he repeated. ‘I feel like I should settle down there.’

‘Where? In the labourers’ basti?’ Prabha could not keep herself from taunting him.

‘The labourers’ basti…?’ he said, as if he were repeating a newly learned word.

‘Ever been there?’

‘No.’ It was then that he realized he had never seen the basti where the factory’s workers lived. When he spoke of beauty and peace, his vision was filled by his own bungalow and its rose-filled garden. Every time he could, he would spend a few hours there and return with the indelible memory of those colourful, smiling roses in his mind. Suddenly, he was reminded of something else.

‘Our new driver is from there,’ he said. ‘Last time, when we were driving from Pune to Bombay, the car had broken down in Lonavala. It was winter. We reached a hotel and I asked him sleep in my room. He threw a blanket on himself, lay down on the floor and woke up straight next morning. And I? Kept tossing and turning on the soft bed. When he woke up, I couldn’t resist from asking him how he could sleep so deeply. Do you know what he said?’

‘He said, ‘We serve you people, we eat what you give us, and we sleep carefree. But you, you are big people, you have hundreds of responsibilities, a thousand troubles,’ isn’t it?

‘How do you know that?’

‘It’s written in every primary school textbook.’

‘Are you being sarcastic?’ Subodh Kumar asked harshly.

‘No, I just mean these are cliches, their importance…’

‘Is there.’ Subodh Kumar interrupted and ended the argument.

‘You know,’ he paused a bit. ‘This money troubles me. I feel embarrassed by it. Money is to be used, it is a tool, it cannot bring happiness. Can’t you see this? I just want peace, sympathy, from people, from nature. Not money. But you cannot understand this because all you want is money.’

‘No,’ Prabha fumed. ‘I don’t just want money. I have enough. But I am sure your workers who live in those bastis definitely want some money. Have you ever thought what this beautiful rain means to them?’

‘I will see that too. I will stay there three days,’ he replied stubbornly.

‘What about me?’ she asked, startled.

‘Why, what problem do you have here?’ he asked harshly.

‘I have a show in Delhi in three days’. You won’t see it?’

‘I don’t know.’

Prabha teared up. Why did she have to argue needlessly? If Subodh doesn’t come, who will buy all the unsold tickets? If half the hall is empty, it’d be terrible for her reputation. She was annoyed at having been woken up early, which is why she’d ended up behaving stupidly; otherwise, she would have never got into a debate about his emotions.

‘Governor Shah is the Chief Guest,’ she said, ‘You invited him. If you’re not there…’

‘So?’ he replied angrily. ‘Am I his servant?’

‘No, that’s not what I meant,’ she hastily added. Today, everything was turning into an argument.

‘Then?’

‘See,’ she said in a tearful voice, ‘the show is to aid the flood victims. If you don’t buy the tickets, won’t those poor people suffer so much more?’

‘Oh!’ he fell into thought.

‘If you don’t come, I won’t do the show,’ she cajoled.

‘Fine, I’ll try to return in time.’ He melted.

*

Upon reaching Belapur, he discovered that the heavy rains had caused flooding everywhere. He saw the manager, Mohan Prasad, running towards the car as soon as it stopped with an umbrella in his hand. With him were six or seven other men.

‘The plane did not land, Sir! We thought you won’t be able to come today,’ Mohan Prasad said as he opened the car door. “It’s rained a lot.’

‘I want to see the workers’ colony,’ Subodh Kumar ignored the open door and did not alight.

‘But, Sir, there is no workers’ colony,’ a surprised Mohan Prasad replied. ‘There is a plan. For it you have to …’

‘Don’t ramble,’ Subodh Kumar interrupt, ‘they must live somewhere.’

‘But those are kachcha houses. With so much rain, that place would be completely water- logged by now.’

‘Which is why I want to see it,’ he yelled.

Mohan Prasad understood: this was one of those instances when reasoning with Chairman Sahib was pointless. He sent the men accompanying him to gather the workers and bring them to the basti and figure out some way, using whatever stones and bricks they could find, to make some sort of place to stand. He closed his umbrella and got into the car with Subodh Kumar. A little further, they would have to leave the car, since the road was kachcha and sloping. There was no other way but to walk. Thank goodness, at least the rain has stopped; else, even a single step would have been impossible.

*

At 2:00 in the afternoon, Baliya reached the factory’s Welfare Office and found a large crowd already there. Nevertheless, she pushed her way through, and somehow managed to get the food. She saw there was khichdi, a curry, pickles, and a sweetmeat too. Ah!

‘Blankets will arrive by tonight. You’ll get them then,’ the man distributing the food said.

‘Thank you, may you live long,’ Baliya replied and headed straight for the hospital. Compounder Babu was sitting outside.

‘How is Sheru’s uncle now?’ Baliya asked.

‘Who, Ramadeen? He’s conscious. Okay now.’

‘Brought him some food. Can I give him?’

‘Yes, go, give.’

As Baliya was going in, she saw Doctor Sahib himself coming out.

‘Where are you going?’ he asked.

‘Ji, err…he…’

‘She is going to give Ramadeen food, Sir,’ the compounder filled him in.

‘No need, he’ll get some,’ the doctor said.

‘Dactar saab, he’ll be okay, no?’ Baliya asked.

‘Yes.’

‘How many days?’ she asked timidly, afraid the doctor might get annoyed at her questions.

‘It will take some time. There is phlegm in his chest. You people always come after it’s already very bad.’

‘No injiction?’

‘Yes, yes, he will get an injection too. You people think if there is no injection, there is no treatment, eh?’

‘No, no, Dactar Saab, I’d have to buy it so…’

‘No need. We’ll take care of everything.’

What kind of day was this, Baliya thought, when there was free food, free medicine, and new pukka houses.

‘When God comes to earth, only then such things happen,’ she exclaimed.

‘What?’ the doctor asked.

‘Our Chaarman Saab. He’s God’s avatar on earth, Dactar Saab!’

‘Yes, why not!’ the doctor smiled.

‘Now Ramrajya will come.’

‘Chairman Sahib will leave in a couple of days.’

‘When will he bless us with his appearance again?’ Baliya couldn’t quite get the doctor’s drift.

‘Of course, he will appear again, but in what form cannot be said.’

‘Why Saab?’

‘Nothing, nothing!’ the doctor smiled once. ‘You go, eat the khichdi! Ramadeen has been admitted to the hospital on an auspicious day. He’ll be fine.’

*

‘I had never imagined our workers live in this plight,’ Subodh Kumar commented pityingly when they were returning from the basti. ‘You never brought this to my attention.’

‘Sir, there was talk about building a colony; but expansion in the factory was going on. Not enough funds so…’

‘It is a shameful thing, Mohan Prasad, to think of money at a time like this.’

‘Ji, Sir.’

‘The workers’ colony should be ready by Diwali. I will arrange the funds. Prepare an estimate and show it to me today itself.’

‘Today! Sir, how is it possible today? We will have to ask the architect to make it. It will take time.’

‘Fine! Then have it ready by tomorrow evening. Before I leave. No, Mohan Prasad, I will not

tolerate any more delays.’

At 10:00 pm that night, after a light dinner, Subodh Kumar entered his bedroom and found deep silence all around. No hustle-bustle, no excess. The room was cool and the bed comfortable. On a stand nearby, his favourite Romantic author Thomas Hardy’s books were arranged, and on a corner table, the white flowers of rajnigandha, whose sharp sweet scent was captured in the room because of the air conditioner and made the surroundings feel like a garden in bloom. This peaceful environment was what he had dreamt of every so often. Yet, who knows why he did not feel at peace. He brought the book to the bed, but he neither lay on the bed, nor opened the book. He lifted his foot to climb onto the bed’s spotless white bedsheet, only to discover his feet were still covered in muck. No matter how many times he’d washed them, the feeling of uncleanliness just wouldn’t go away.

The sight of that dirty gutter of the labourers’ basti is set in his mind’s eye. The dirty water choked with puffy wood, boats made of torn paper, rotten vegetable peels. He looks away but the image comes back unbidden. Even if that image disappears, what is there to see? The same naked, grimy, sticky children, eyes rheumy, noses flowing non-stop, legs slathered with mud. The long dirty gutter, with its long thin threads of black muck, and among these, those children floating boats made of garbage, unaware of their disgraceful state, those children whose sight can make him weep but cannot make him touch them. Once again, he felt the pressure of that wailing woman’s body on his feet, and smelt the stink of perspiration rising from her. His body shrivelled with disgust. Simultaneously, he also felt disgust towards himself for his visceral reaction. He was beginning to understand that in this unsettling silence, the contrary man inside him couldn’t bring his paradoxical sides to coexist peacefully. He needed a third person, to tolerate whom, his contrary sides would have to fold into each other and become one again. He sat in a state of undecidedness, wondering what to do, when the factory’s siren began to screech. The suddenness of the screech hit him like a hammer. Anguished, he immediately picked up the phone and summoned Mohan Prasad. ‘I am leaving for Benares right away. Have the estimate prepared and bring it to me there.’

At midnight, when he reached Benares and woke Prabha up, she felt less surprise, more pride.

‘You’ve left your heaven so quickly?’ she lovingly laughed.

‘That is not heaven, it is hell, hell, where humans live and breed like dirty insects in gutters!’ he spoke with such vehemence that she shrank from him.

‘But I did not run away in fear from hell. I have come because I wanted you.’ He dug his fingers so deep in her shoulders that his fingernails sank into her flesh and she whimpered.

He was deliberately being cruel.

‘To have you brought over all the way and then not spend time with you would be foolish,’ he said carelessly.

By being cruel to a woman, he was merely trying to regain his hurt self-respect. That’s all.

*

‘So much blasted sleet,’ Ramadeen complained as he put an oil lamp on the thatched roof.

‘Dry or rainy, ordinary day or festival, you have to curse,’ Baliya immediately rebuked him.

‘So? There’s ice forming under the thatch. What has minejment done for us? Remember, right here, Chaarman Saab had stood and promised. By Diwali pukka houses will be ready. What happened to that?’

‘Arre, he only said so,’ Baliya was an optimist, not a pessimist.

‘How dare they not do it? Workers have promised, no one will take sweets this time. We will form a procession and march on the manager’s house. If he doesn’t agree, we will do istrike.’

‘You’ll also do istrike?’

‘Why not, have I worn bangles?’

‘Do istrike! What’ll you eat then? Stones?’

For an instant, a wave of panic ran through Ramadeen’s eyes. Then he stood erect and said, ‘You lowly woman! Always grabbing for things to stuff in your stomach!’

‘He is lowly who gets swayed by others,’ Baliya raged, ‘You’ll do istrike! When you had collapsed into a heap in front of Chaarman Saab, remember? If he wasn’t there, Munna and I would be mourning you.’

‘What did he do?’

‘Didn’t he? Didn’t he make those men carry you to the hospital? How many medicines and injictions they gave, only then you got better.’

‘As if they had a choice. The hospital is for factory’s workers.’

‘Oh ho, as if they had a choice! Does anyone get free food? Does anyone get free injiction?’

‘If they don’t give, then it is the minejment’s fault,’ Ramadeen forcefully repeated.

‘Have you no shame! He who gave you life, you’ll istrike against him?’

Ramadeen’s eyes filled with hesitation. He is not ungrateful, doesn’t want to be ungrateful. But what Baliya is saying is not the whole truth. The leader of the Workers’ Union says something entirely different. His words overpower Baliya’s words.

‘Then why did he lie?’ he said.

‘So what? He felt like it, he said it. He saved your life. You should be his servant all your life.’

‘Stupid woman,’ Ramadeen roared ‘we labourers are workers of the factory, not anyone’s servants!’

‘Not servant, an ingrate’ Baliya screamed.

‘Shut up bitch! If you open your mouth again, I’ll smack your face.’

‘Hit me! Why don’t you? Who are you trying to scare?’ Baliya screamed even louder.

Quaking, Ramadeen grabbed her plait and dragged her. He threw her on the ground and kicked her crouched back hard a few times. He spat out a stream of abuse, ‘Lowly! Bitch! Foul woman!’

Screaming abuses at her, he stomped out, leaving her heaving and sobbing. Then he straightened his clothes, puffed out his chest, lifted his head high, and swaggered off towards the Workers’ Union Office.

*

When he woke up in the morning, Subodh Kumar was terribly embarrassed by his behaviour the previous night. He was a cultured man, a lover of art and beauty; that animal behaviour did not befit him at all. He was feeling so small in front of Prabha that to feel equal to her once again, he felt compelled to exhibit to her the largesse of his mind.

‘When do you want to go to Delhi?’ he asked, ‘I think I will also come along.’

‘The show’s tomorrow! If I got there today, it’d be good. I could meet the manager. There was also some talk about meeting some people from the press,’ Prabha replied sadly.

‘Okay, we’ll go today then,’ he said benignly.

‘Okay’, Prabha was still sounding put out.

‘I also have to buy you a present,’ he was still trying to make up.

‘Give me a present later. You had promised that if the show went well, you’d give me something brand new,’ Prabha reminded him. She had figured out that he was trying to please her.

‘Oh yes, how did I forget? The show will obviously go well. Your dance is flawless. We’ll buy it today itself, you can wear it during the show. A sapphire necklace! It will suit you very much.”

Just then, the phone rang. When he turned around after finishing the conversation, Subodh Kumar was a different man. His body erect, his face flushed, nostrils flaring, and eyes flashing. Only gamblers can understand this brightness. It is possible that when he was betting Draupadi and all his retinue, Dharmaraj Yudhisthir’s eyes had the very same brightness.

Excitedly he told her, ‘Now that’s what I’m talking about! No necklaces. I am giving you shares worth a lakh. You’ll make a profit of a full five lakhs. The agent from Calcutta had called. Sadanlal’s shares are selling low but the market is climbing high. A five-fold profit is guaranteed, minimum. One lakh in your name.’

‘What if the prices don’t rise!’

‘Impossible! If that happens, I will give you five lakhs of my own.’

The next day, when Mohan Prasad brought the paperwork to Benares, he was informed that Subodh Kumar has left for Delhi. They spoke over the phone, and Mohan Prasad was ordered to travel to Calcutta after three days. Then suddenly, Subodh Kumar’s wife took ill and he took her to Kashmir to recuperate. As they were leaving, he gave orders not to be disturbed under any circumstances while he was away. Mohan Prasad finally got to meet him only a month later in Calcutta.

As soon as they met, Subodh Kumar said, ‘I need five lakh rupees. Send it from the Belapur Company accounts.’

‘Five lakhs, Sir? As you well know, expansion work is on. Retail is not doing well,’ Mohan Prasad replied, stunned.

‘I don’t care! I need the money. I have to give it to someone. Had bought shares, went into a loss. No matter how, please arrange this money. Such a big company, we pay lakhs in taxes, can’t I get some money out if I need it? What silliness!’

‘Okay Sir, I’ll do something.’

‘Do it fast!’

‘Yes Sir. I have also brought the estimate. Please see it.’

‘What estimate?’

‘For the workers’ colony. It’s come to fifty lakhs. We need five lakhs immediately to start.’

‘Five lakhs?’

‘Yes Sir!’

‘Can the company bear this expense?’ he asked in the pointed laconic tone of a businessman.

‘Very difficult Sir, almost impossible.’

‘Arrange for a loan from the bank.’

“It’ll take time.’

‘Let it take time! After all, how much time will it take? Arre Mohan Prasad ji, use your brains sometimes!’

Mohan Prasad returned home. After a lot of thinking, legal and accounting acrobatics, he managed to arrange five lakhs for Subodh Kumar. But the arrangements for additional money got stuck in innumerable red tape loops. Who knows how much more time it will take!

******

Author’s Note I, Mridula Garg, author and copyright holder of the story “Tukda-tukda Aadmi” give Pooja Sancheti the permission to publish her English translation of the story in The Beacon magazine.

Translator’s Acknowledgement I would like to thank Ms Mridula Garg for permitting me to translate her story and for her inputs. My sincerest gratitude to Prof Alok Bhalla for his encouragement and his insights which he offers ever so kindly, even at the shortest of notices.

Dr Pooja Sancheti is an Assistant Professor in the Humanities and Social Sciences Department at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER) Pune, India. Her current academic interests are South Asian Anglophone fiction, transnational literature, women’s writing, magical realism, and postcolonial theory. She is also an amateur Hindi-English translator. She also dabbles in the interdisciplinary domain of language and science and teaches EAP, a parallel research interest.

Also Read by Pooja Sancheti: Reading Manjula Padmanabhan’s Harvest in 2022

Mridula Garg in The Beacon

Leave a Reply