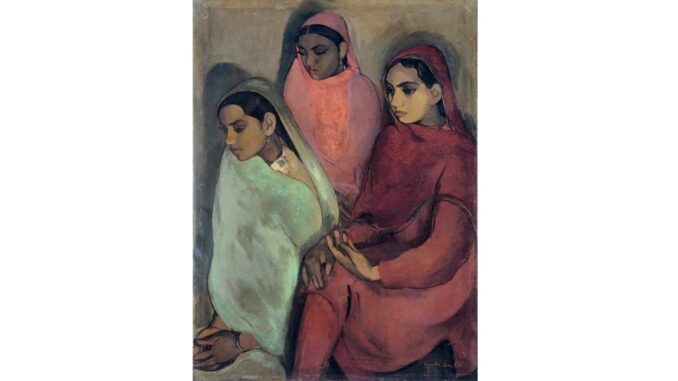

Three Girls. Amrita Sher-Gill

To Pandit Nehru and Qaid-e-Azam Jinnah,

I trust that until now, neither of you would have received a letter from a prostitute. In fact, I have full confidence that neither of you would have ever set sight on me or any other woman of a similar persuasion until today. I know too the extent of impropriety that lies in my writing a letter to you, and that too an open letter. But what else can I do? The circumstances are such, and these past days–the demands these girls make are so pressing–that I cannot stay without composing this letter.

Why are Bela and Batool making me write this letter? Who are these two girls and why are their claims so insistent? Before I explain why, I would like to tell you a bit about myself.

Do not be concerned! I am not about to narrate to you the details of my despicable history. I will also not reveal when and how I came to be a prostitute. I do not come to you to elicit your false compassion, using the pretext of some aspiration to respectability. Recognising your compassionate heart, I do not wish to spin you some yarn about a failed romance as a justification. My intention in writing this letter is also not to acquaint you with the covert arts and ruses of courtesanship. I have no wish to explain myself. I merely wish to tell you a few of those aspects of my life that I believe will, going forward, have an effect on Bela and Batool’s life.

Both of you must have visited Bombay several times; Jinnah sahib has of course seen much of it. But neither of you would have ever had any earthly reason to see our bazar, the bazar I live in, which is called Farris Road. Farris Road is located between Grant Road and Madanpura. On the other side of Grant Road lie the areas of Lamington Road, Opera House, Chowpatty, Marine Drive and the Fort, where the gentlefolk of Bombay live. On this side of Madanpura, the poor live in their settlements. Farris Road is in the middle of the two, so that both the rich and the poor can equally profit from it. Though, in truth, Farris Road is closer to Madanpura, because the distance between indigence and prostitution can never be too great.

It is not a pretty bazar by any means. Its buildings are not beautiful either. Night and day, it is filled with the sounds of trams rattling through the middle of it. All the world’s stray dogs, ruffians, creatures of cruelty, cripples, consumptives, reprobates, lechers, voyeurs, balding syphilitic and clap-ridden wastrels, cokeheads and pickpockets, lacking an eye or a limb, strut around it, their chests thrust out. Filthy hotels, mounds of rubbish piled high on dank and grimy pavements upon which lakhs of flies buzz constantly, misery-laden heaps of wood and coal, professional pimps and purveyors of wilted garlands, vendors of rotten pulpy books about the cinema, shopkeepers vending sex manuals and naked pictures, Chinese barbers, Islamic barbers, and strongmen who gird their loincloths tight as they mouth off a string of abuses—on Farris Road, could be found all the refuse of man’s social existence.

Obviously, you could never have visited this place. No respectable person ever strays in this direction, because all the decent people there are, live over on the other side of Grant Road; and those who are even more so, make their residence on Malabar Hill. I had once passed by Jinnah Sahib’s mansion there, and I paused to bow down in salaam. Batool was with me too—I can never quite express the reverence that that girl has for you (Jinnah sahib). If there is anyone that she loves in this world second to God and his Prophet, then it’s you. She has a picture of you that she wears in a locket, close to her heart. But not with any bad intentions, Batool is only eleven years old, she is only a little girl. Yet, already these people in Farris Road have hideous designs on her…I’ll tell you about them another time.

This is Farris Road, where I live. On its western end, at the corner of a dark alley from where the Chinese barber has his shop is my shop. Others would not call what I have a shop of course, but you are men of wisdom, so why should I dissemble to you. So I will say that this is where my shop is, and that it is the place where I ply my trade, just as a grocer, vegetable vendor, fruit seller, hotel owner, mechanic, cinema owner, clothes store owner, or any other shopkeeper carries out his business. Just as he looks to the satisfied customer as well as his own profit in each transaction, so do I. My business is just like theirs; the sole difference is only that I do not deal in the black market. In all other respects, there is nothing that distinguishes these other vendors from me.

My shop is not well situated. Let alone the night, visitors can only stumble around it even in the day. The men that come here only depart this dark alley with their pockets emptied, drunk out of their senses, spewing the worst abuses in the world. The most trifling event can result in a knifing. Every two or three days, a murder is sure to take place. In other words, not a day passes without one’s life being at risk.

And then I am not some high quality prostitute who can move to Pawanpul, or set up residence in Worli, in a nice house on the seashore. I am a prostitute of an extremely ordinary rank. Once I may well have seen all of Hindustan and drunk water from every one of its rivers and spent time with people from every rank and walk of life, but since the past ten years, I have just been here, in this city of Bombay, in this very shop on Farris Road.

Though, as I say, it is not a nice place. It smells, and there is slush and sludge everywhere, and mangy dogs rear up from up from every corner to bite the frightened customers. But nevertheless I make up to six thousand rupees a month.

My shop is a single storied house, with two rooms. I use the front room as my sitting room. In it, I sing and I dance, and I seduce the customers. The room at the back serves as the bedroom, kitchen and bathroom. At one end of the room, there is a water tap. On one side is an earthenware vessel. Opposite it, is a large bed, underneath which there is a smaller bed; underneath both are the trunks in which I keep my clothes. The outside room has an electric light, but the inner one is completely dark. The landlord has not had the walls of the house painted for years, and nor is he ever going to do so. Who has that amount of time to spare.

My entire night in spent in singing and dancing for the customers in the sitting room. In the daytime, I just lay my head on the bolster and fall off to sleep right there. The back room is occupied by Bela and Batool. Often, when the customers go into the back room to wash their faces, Bela and Batool stare at them with their wide-open eyes. The things their gazes speak of, this letter of mine says them too.

If these two had not been with me, this sinful woman would never have dared to be so presumptuous. I know the world will spit on me, shun me. It could very well be that you will never see this letter. But I am determined to write it anyhow, as Bela and Batool will it to be so.

Perhaps, your guess is that Bela and Batool are my daughters. No, it is not so. I have no daughters. I bought these two girls in the bazaar, in the days when the Hindu-Muslim riots were at their height, and human blood was being let like water on Grant Road, Farris Road and Madanpura. Then, I bought Bela from a Muslim procurer for three hundred rupees. This Muslim procurer had brought her to Bombay from Delhi, to which she had been brought by another Muslim procurer from Rawalpindi.

Bela’s parents had lived in a lane opposite Poonch House in the Raja Bazar in Rawalpindi. The family was middle class, the concern for respectability and simplicity was the tonic of their existence. Bela was her parents’ only child. When Rawalpindi’s Muslims started to cut down its Hindus with their swords, she was studying in grade four.

The date of the incident was the 12th of July. Bela returned home from school to see a huge mob swarming outside her and other Hindu homes. The mob was armed and it was setting fire to the houses, dragging the people, their children, their women, out of their homes and murdering them on the street. As they did so, they chanted the slogan of ‘Allah-o-Akbar’ all the while. Bela saw her father being done to the death before her eyes. And then she saw her mother breathe her last before her eyes. The savage Muslims had cut off her breasts and thrown them away. Those breasts with which a mother, any mother, a Hindu mother or a Muslim mother, a Christian mother or a Jewish mother, suckles her child and ushers in a new chapter of creation in the world of humans and the universe’s multitudes. Those milk-laden breasts were hacked away to the sound of slogans of Allah-o-Akbar. Some had thought up such creative brutality. A cruel darkness had inked their souls with blackness. I have read the Quran and I know that what was done to Bella’s parents in Rawalpindi was not Islam. It was not human. It was not even enmity. Nor was it revenge. It was a brutality, a callousness, a cowardice, and a satanism that burst darkly in the breast, which stains even the last glimmer of light.

Bela is now with me. Before me, she was with the bearded Muslim procurer, and before that she was with the Muslim procurer from Delhi. Bela was no more than twelve years old, when she studied in the fourth grade. If Bela had been at home, she would now be moving up to the fifth grade. Then, when she would be grown, her parents would arrange for her a marriage to a young man of modest means from a respectable family. She would make her own little world, with her husband, her little children, content in the small happinesses of her domestic life.

Today, this tender little bud has been subjected to an early autumn. Now Bela no longer looks as if she is twelve. Her years are young, but her life is very old. The fear in her eyes, the bitterness in her humanity, the blood of her despair, her thirst for death; if you could see it, Qaid-e-Azam Sahib, you may be able to understand. Perhaps you could divine what lies behind the bleakness of those eyes. You are a respectable man. You must have seen the innocent girls from respectable families. Hindu girls, Muslim girls. Perhaps you would see that innocence has no religion, that it is something that all humanity holds in trust. It is a bequest to the whole world. The man who destroys it can never be forgiven by any god of any religion.

Batool and Bela live together as sisters in my house. But they are not sisters. Batool is a Muslim girl. Bela was born in a Hindu household. Today both of them live together in a whore’s house on Farris Road.

If Bela came from Rawalpindi, Batool came from Jalandhar. She is the daughter of a Pathan from a small village named Khem Karan. Batul’s father had seven daughters –three were married, four were unwed. Batool’s father was an ordinary small farmer in Khem Karan. A poor Pathan, but a proud Pathan; who had been settled in Khem Karan for centuries. Only three or four households were Pathans in the village of Jats.

Panditji, you may appreciate the patience and peace with which these Pathans lived, when you consider that despite the fact that they were Muslims, they were not given permission to construct a mosque in the village. The Pathans read the namaaz in their homes without protest; for centuries, ever since Maharaja Ranjit Singh ascended the throne, the muezzin’s call to prayer has never been heard in this village. Their hearts were suffused with spirituality and mysticism, but the worldly constraints were so immediate. Moreover, concerns for liberality and acceptance were so prevalent that they could not dare to utter a word.

Batool was the most beloved of her father’s daughters. The youngest of the seven, she was the sweetest, the prettiest. Batool is so beautiful that her skin flushes if you even touch her. Panditji, you are yourself Kashmiri by origin, and being an artist, you know what such beauty can be. Today this loveliness lies in disarray in my piles of filth, so much so that finding a decent man who will appreciate it will prove difficult. All one ever sees is rotten, dissolute Marwaris, contractors sporting bushy moustaches, and black marketeers with lascivious stares.

Batool is completely illiterate. She had only heard the name of Jinnah sahib. Thinking Pakistan to be a fun spectacle, she had joined in the slogans for it; just as three-four year old children run about the house shouting ‘Inquilab Zindabad’. She was only eleven years old after all.

Little, unlettered Batool. It’s only been a few days since she has come to me. A Hindu procurer brought her to me. I bought her for five hundred rupees. This Hindu procurer had brought her from Ludhiana, from a Jat one. Where she was before this, I cannot say. Yes, the lady doctor has said many things to me, but if you were to hear them, you would perhaps go mad. Batool is half mad herself. The Jats killed her father with such mercilessness that the past six thousand years of Hindu culture was stripped of its skin, and human barbarity in its savage, naked form has been laid bare for all to see.

First, the Jats gouged out his eyes. Then they pissed into his mouth. Then they slit him from the throat down and disembowelled him. Then they forced themselves on his married daughters and sowed their own humiliation. Right in front of their father’s corpse. Rehana, Guldarakshan, Marjana, Sausan, Begum… one by one, barbaric man defiled each one of the idols in his temple. The ones that gave him life, who sang him to sleep with a lullaby, the ones that had bowed their heads to him, in shame, in subjection, in chastity. With all these sisters, these daughters in law, these mothers, they engaged in fornication.

The Hindu religion lost its honour, it destroyed its tolerance, it erased its own greatness. Every mantra of the Rg Veda was silent today, every couplet in the Granth Sahab was ashamed, every verse of the Gita was wounded. Who is it that would dare speak to me of the artists of Ajanta? Narrate to me the texts of Aśoka’s inscriptions? Sing praises to me of the idol makers of Ellora? In Batool’s forlorn, tightly bitten lips, in her arms marked with the teeth of the feral beasts, and the instability of her leaden legs is the death of your Ajanta, the hearse of your Ellora, the funereal shroud of your culture. Come, come, let me show you the beauty that once was Batool; come let me show you the stinking corpse that Batool is now.

I realise that, overcome with emotion, I have said too much. Perhaps, I should not have said all this. Perhaps, it will cause you embarrassment. Perhaps, no one has ever uttered, or reported, such impertinent words to you before this. Perhaps, you yourself feel all this, but can do nothing. As far as I can see, both of you, Panditji and Jinnah sahib, you cannot do all of what needs to be done; in fact, it does not seem that you can do even a little bit. But even then, freedom has come, to India and to Pakistan both, and perhaps even a prostitute certainly has the right to ask her representatives: What now will come of Bela and Batool?

Bela and Batool are two girls, two communities, two cultures, two cultures, two mosques and temples. These days, Bela and Batool live with a prostitute, who runs her business in a shop close the Chinese barber’s on Farris Road. Bela and Batool do not like this trade. I have purchased these two girls; if I want, I could get the work done by them too. But I think that I will not do that which Rawalpindi and Jalandhar have done to them. So far, I have been able to keep them away from the world of Farris Road. Even then, when my customers go to the back room to wash their hands and faces, Bela and Batool’s gaze begin to speak to me. I cannot bring to you the heat of their gaze. I cannot also adequately convey their message to you. Why don’t you read the ciphers in their gaze yourselves?

Panditji, what I want is that you make Batool your daughter. Jinnah Sahib, I wish for you to consider Bela your ‘daughter of the auspicious stars’. Just for once, extricate them from the clutches of Farris Road, keep them in your homes. Pay heed to the laments of the lakhs of souls, that dirge that resounds all the way from Noakhali to Rawalpindi, from Bharatpur to Bombay. Is it only in the Government House that it cannot be heard? Will you attend to this voice?

Your sincere friend

A prostitute from Farris Road

***

“Any knowledge that doesn’t lead to new questions quickly dies out: it fails to maintain the temperature required for sustaining life. This is why I value that little phrase “I don’t know” so highly. It’s small, but it flies on mighty wings. It expands our lives to include spaces within us as well as the outer expanses in which our tiny Earth hangs suspended.” —Wisława Szymborska

******

Courtesy the author. Posted by her on August 22 2022 on: https://ayeshakidwai.hcommons.org/एक-तवायफ-का-खत-कृष्ण-चन्दर-194/

Ayesha Kidwai is a Professor of linguistics at Jawaharlal Nehru University. She is also a translator between Urdu/Hindi and English. Her most recent book-length translation is of Anis Kidwai’s Dust of the Caravan was published by Zubaan in 2020.

Also Read her translation: The Mughal-born [Mughal Baccha]: Short Fiction by Ismat Chugtai

Krishn Chander (23 November 1914 – 8 March 1977) wrote in Urdu and Hindi, penning over 20 novels, 30 collections of short stories and scores of radio plays in Urdu. He also wrote screen-plays for Bollywood movies to supplement his meagre income as an author of satirical stories. His novels (including the classic: Ek Gadhe Ki Sarguzasht, transl. 'Autobiography of a Donkey') have been translated into over 16 Indian languages and some foreign languages, including English.

This letter hurts.

Aptly summed up by a college friend who just read it too:

“This letter has silenced me. Thanks for the share Pankaj”

Krishn Chander lives. In every letter of every word that he writes. And Ayesha Kidwai does him great justice.

Thank you The Beacon for sharing such brilliance.

Powerful.

Very powerful.

And it has a salience today, as much as it had in 1947, maybe even more.

Thanks for sharing this.

Need a steel heart to empathise the brutalities the masses bear to political turmoils. The leaders are always safe though they are the ABETTORS in LAW

Thank you for this. More people should read this simple yet powerful story to acknowledge the depravity that humans are capable of and its terrible consequences.