“Game fights, street fights, theatre fights, gala fights, festival fights…”. Borrowing Wazim’s words, these are further categorised into three kinds: “the fight that hurts the physical self, the emotional self and then finally, the male ego”, which is supposedly the most disastrous of all three.

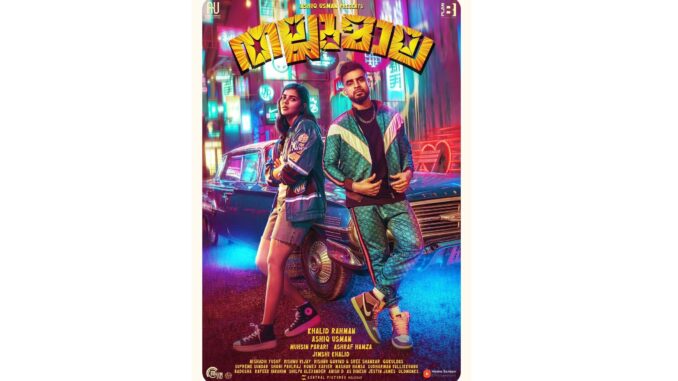

Directed by Khalidh Rahman and co-written by Muhsin Parari and Ashraf Hamza, Thallumaala is an action-comedy film that is loaded with, as the title itself says, ‘a string/chain of fights’. Wazim (played by Tovino Thomas) is your infamous, angry kid whose only form of self-expression is violence. The entire plot of the movie is connected through fights, some contextual, others random. The recurring theme that ‘Thallumaala’ so passionately engages with, is ‘the art of fight-making’.

The movie is spontaneous, loud and blasts-in-your-face kind of colourful. The first half is entirely used up to set the mood and atmosphere for the relatively event-filled and creatively better made second half. The former does drag a bit to establish the mood of the movie; but the latter half, when the chaos unfolds and the tension leading towards the climax attempts to make up for it.

The savarna-dominated Indian film industry, which has a ratio of about 6.2 men to one woman, with many upper-caste men working behind the camera as directors, writers and producers, has only distributed one gaze across all screens since the beginning of Indian cinema.

This is a gaze that has only portrayed surma-lined, skull-cap clad Muslim men crossing the border, or dark-skinned, violent and villainized Dalit men who needed to be killed, or wretched, under-privileged Dalit men who needed saving, which is simply a form of poverty porn for a middle-class audience.

With scriptwriters like Muhsin Parari, there has been a shift in the Malayalam movie industry as far as Muslim representation and stereotypes are concerned; films like Sudani From Nigeria, KL 10 Pathu, Virus and now, Thallumaala, all have Muslim (read: male) characters living normal Muslim lives, exhibiting their native pride in the language(s) they speak and the culture they are from.

As Zaki Hamdan puts it in his review Thallumaala: The Ethics of Brawling (Maktoob Media), the “everyday Muslimness” or the “Lived Islam” they live with on a daily basis is what really constructs the actual Muslim-ness in those characters, instead of a strictly theoretical or visible understanding of Islam. The Muslim body does not try to prove its worth by being a moral being who attempts to sanction his religiosity with ethical correctness. Such beings are chaotic, wrong, loud and messy. They make mistakes and they get into brawls that will go so far as to burn down an entire theatre, yet remain loved in the community as their own.

There have been many takes on the action/stunt-making aspect of Thallumaala already published on various platforms, i.e. the technical brilliance in which the stunt choreography has been conceived (Moviecrow, Ashwin Ram), or the “attempt to represent the Islamic ethics of violence” (Maktoob Media, Zaki Hamdan), or even the view that “the theme of the film is itself toxic male ego and masculinity and how much influence it will have on the new generation is a concern.” (FanaticBuff, Jerey).

There is, however, one common factor that resurfaces (or ironically, never surfaces) in all these reviews: the mention of a character called Beepathu, played by Kalyani Priyadarshan. In between all this testosterone-filled chaos, there lies Beepathu, your popular, Malabari vlogger based in Dubai, who, upon her return to India for her higher education, meets Wazim. There are only two events in the life of Beepathu and they revolve around marriage— one, her engagement to Wazim, that gets called off due to which, two, she gets engaged to another man. Even though her education is mentioned at least once or twice in the whole movie, she appears least interested in it, and is seen going back to Dubai for her second engagement. Her five-minute cycling sequence and being internet famous for inheriting her rich, Arab dad’s wealth, are all that the film uses to establish her character. So if the film’s reviews forget to mention Beepathu, they could hardly be faulted for their conscious/unconscious “erasure.” One should really be asking— is there, after all, anything to erase?

![]()

Having a male- dominated cast & an all-male crew, it is a given that the film will not provide us with accurate “women representation.” But the male gaze generates two major types of women— the cutlery-wielding mothers who scream at their boy children to eat the food while its hot and the ever-so-gorgeous Beepathu and her friends who walk down the streets of Dubai in fabulous haute couture.

These characters are not brought into being out of a void; they are, in fact, the genuine reflection of the makers’ life in the town of Ponnani and the kind of women they come across on a day-to-day basis as well as the spaces they see these women occupy— the kitchen & the internet.

Beepathu was intended to be Wazim’s romantic interest, someone for whom he would try to turn over a new leaf, someone who would make him give up his chaotic, violent and immature self; as is the role for usual heroines in Indian cinema, who are fated to die in order to give birth to the redeemed, flawless hero we are left with to celebrate. I wouldn’t say Thallumaala attempts to take that route at all; the movie stands out in its regional and cultural setting, plot and style of making, and the politics of visibility and Muslimness, but when you have an imbalance of gender behind the camera, the nuances of that said route is much-less a choice and more of an unconscious and gendered performance.

However much it may vary in its methods/style of execution, that imbalance is reflected in the characters, both male and female, storyline, and also shapes the politics of visibility and overtones of religion/ Muslimness.

For example, the lyric in ‘Tupathu’ that goes, “I’m an oil field, mone. Historical war-zone, mone”, (roughly translated to “I’m an oil field, son. Historical war-zone, son”) where Pathu is being referred to the west-Asian regions of conflict, is a a very recurring pattern in men’s literature, where women’s bodies are often used as metaphors for home-lands, fields and war-zones, ymbolising sacredness and chastity, and the tragedy of being destroyed, stolen, displaced or hijacked by the oppressor.

When talking of gender, Thallumaala, if anything, does manage to dismantle Muslim women’s portrayal through one important factor— physical appearance, which otherwise comes in Malayalam cinema in the form of either— ‘Shahana’ from Ustad Hotel, who sneaks out of her home’s compound in an Abaya and instantly transforms into a party-going, rockstar upon reaching the pub, or ‘Sameera’ from ‘Take Off’, who is pressurised into wearing an Abaya from her in-laws while going to work, or ‘Sulu’ from ‘Meow’, who is only seen in a Niqab outside of her home but occasionally pulls it up to wink and tease at her to-be husband (I know, what?). Here, Beepathu is seen wearing all kinds of clothes— entirely graphic stylish outfits, salwar-suits with a veil on her head, sports jerseys, jumpsuits and even full length, sleeve-less white wedding gowns. Ultimately, with the “esarp” styled hijab donned on her big wedding day, she completely confuses the audience that is used to a singular, stereotypical portrayal of a Muslim woman that always falls into the traditional/modern binary of oppression/freedom respectively, depending on how much of her skin was covered. But Thallumaala’ s take on gender stops with the physical appearance of Muslim women.

Wazim might claim to be madly in love with Beepathu, and it might seem like Beepathu’s significance and uniqueness lies in Wazim’s obsession/love towards her and wanting to marry her but, this is only convincing up until we shake off the male gaze from within us. A truer love is actually found elsewhere in Thallumaala. A much more natural and intense one that takes place if one looks closely enough— that of Wazim and Reji (played by Shine Tom Chacko).

Their maiden meeting, the way he asks for his name, their passive-aggressive looks at each other, the glances they steal of each other and especially the way Reji kisses Wazim after beating him black and blue, is a hundred times more intense, and oozes out an insane amount of sexual energy; intense where the exchange between Wazim and Beepathu becomes forced and superficial. This kind of chemistry between Wazim and Reji is not new to cinema.

Hyper-masculinity vis-a-vis homoeroticism in many action-packed movies has been studied closely earlier, especially in the case of ‘Fight Club’. In an article titled ‘Interpreting Fight Club: Masculinity and Homoeroticism’, published on nouse.co.uk, Holmes writes, “In Fight Club, it is a way for men to therapeutically express their masculinity that they have been concealing, through violence…. Moreover, fighting is a way for the men to be physically intimate with each other, whilst still conforming to traditional forms of masculinity which regard homosexuality as unmanly.” Fight Club has popularly become subject to many queer readings and the opinion that it is not the hyper-masculine movie that straight men understand (and relish) it to be is put forward by various queer groups. In Alfonso Cuarón’s Y Tu Mamá También, there is a dialogue that a woman tells the two male leads, “Typical men. Fighting like dogs and marking your territory when all you really want to do is f*ck each other.”

Such a perspective to Thallumaala even renders Wazim and Pathu to be a misfit pair added in the movie just for the sake of the heterosexual vigour that cinema, along with the mainstream mass audience, consider very necessary to make the male protagonist feel “whole”. That way, Thallumaala becomes more than just the ‘the art of fight-making’ for it is also an intense love-making that occurs between these men each time they raise their tightly clenched fists to hit each other.

They love each other because they can inflict physical pain onto each other from which they derive an almost orgasmic pleasure. They are grateful to their ‘enemies’ because they providea battlefield to flaunt their masculine ego that carries emotional, physical and sexual undertones.

This ‘rivalry’, after their initial, physical exchanges, blooms into an unbreakable form of love.

Of course, “boys learn to be men from the men in their lives”. It goes without saying that gender-norms and societal conditioning that men are subject to as they grow up, is what instills so much normalised violence within their bodies. Yet, in the end, this is the reality from where they create friendships, nurture bonds, fall in love, and get their hearts broken (not to mention jaws and bones). This is the reality which directs the course of their lives, where they learn to be responsible, where their actions, which may have been wrong, or hurtful, are attempted to be right-ed; this is the ground on which “boys” learn to become “men”. No matter the dilemma of ethics surrounding it, there is truth in that love and Thallumaala has portrayed exactly that, rather stylistically.

Yet, Ironically, Thallumaala is introduced as a Tovino-Kalyani starrer in many reviews, and Beepathu also takes up a large chunk of the poster-space, not to mention the solo posters and Netflix thumbnails that feature only her.

Now, what happens when a character is shown to be larger than what they are originally intended to be in the work being produced? Especially, when that character is female?

What are the effects of the presentation of a film fuelled by testosterone with a female face that has very little to do with the plot? A face that is known to have a certain market-value? Are the intentions behind such an act, exploitative of gender-power-structures? Most importantly, does it downplay the brilliant work of the other male co-actors in the film, like Shine Tom Chacko or Lukman Avaran?

Angamaly Diaries, directed by Lijo Jose Pellissery, is another movie that, if not similar to Thallumaala, also engages with violence and fight-making. The protagonist has multiple heterosexual relationships, but the female characters are spared from any kind of unnecessary spotlight. At the same time, characters like Lichi (played by Anna Rajan) also have a separate life, devoid of the male protagonist going on of which we know very little, but because of which her character gains more depth. The movie is not marketed with their faces and they take up little to no poster space.

It is that conscious (or unconscious) distance that male creators maintain from the female characters that actually contributes to the characterisation of female characters rather than when the male gaze engages with it.

Anna Rajan delivers her performance with grace, fully mindful of how little it is. In Thallumaala, the drawbacks of Kalyani as an actor do not come into question at all, for the movie does not require Kalyani’s skill or lack of skill thereof. It only requires glam. The heteronormative understanding of romance here not only represses expressions of male love but pushes female characters further onto the sidelines, once again reducing them into objects of visual aesthetic pleasure. The characterisation of Beepathu based on that singular attribute reaffirms the ages old notion that the female character exists only for this purpose. It is a reductive act that is inherently gendered due to which it comes off as quite unsurprising, or non-occurring.

The very fact that the audience does not realise that she is insignificant in the movie and, would go so far as to praise her performance only reflects the tragic truth that, to deliver a female character’s insignificance on screen is a female actor’s biggest achievement.

That is the extent to which the male gaze has blinded us all.

*******

Izza Ahsan is a student of Media and Cultural Studies at the Tata Institute Social Sciences, Mumbai and a part-time musician. When not experimenting with music, Izza writes on cinema, culture, religion & race-caste relations.

Izza Ahsan in The Beacon

Leave a Reply