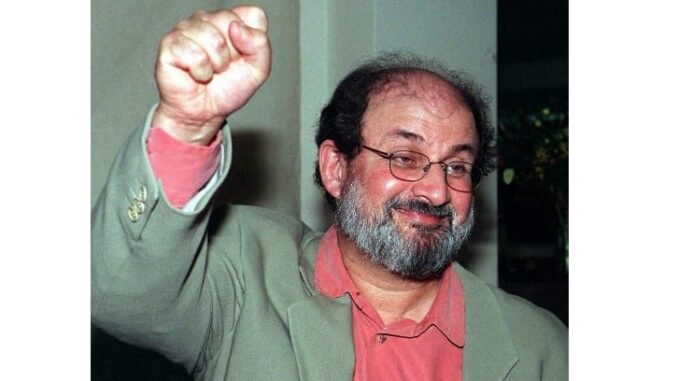

Photograph courtesy AFP

Padmaja Challakere

We live in a time when the world has become fantastically metamorphic, the rate of change is gigantic. In this book, people become prey to various kinds of alterations, and the dread is turned into this mythological being, the djinn . . . who are articulations of our nightmares. One of the things that endeared me about the djinn is that most of them did not believe in God either. That gave me the idea of supernatural beings who break though our reality.

Salman Rushdie, citing George Szirtes, in a talk about his 2015 novel Two Years, Eight Months, and Twenty-Eight Days

O

n August 12, 2022, Salman Rushdie survived a gruesome near-fatal knife attack by a 24-year old Lebanese-American, Hadi Matar. Rushdie’s survival and recovery is a miracle of strength, not only of spleen, sinew, and muscle, but also of a determined optimism, one based on realizing ideals through struggle. A combative “I- will- bloody-show- them” attitude! The “Kipper-incident” from his early teens comes to mind, when a young Rushdie, sent to boarding school in England, was made to eat a plate of kippers as his fellow-students watched him struggle. Every time he tried a forkful; his mouth filled with bones. No one would show him how to eat the fish but as he fought back tears, he also realized that this was a challenge he had to win.

This combative optimism is part of Rushdie’s sense of the heroic. Also, his uncanny sense of humor. An Etonian humor! Extremely witty, inventive, pushing things to their absurd conclusion. Think P.G Wodehouse crossed over with Swift and Cioran and Kipling. British humor with Indian magic. Too cavalier, maybe too allegorical. But essentially a story-teller’s humor, a story-teller’s satire. Not misanthropic; not cynical.

When violence was unleashed on Rushdie in response to the “insult” of Satanic Verses from Khomeini’s fatwa in 1989, and he was forced to move from rental house to rental house in London and live away from his family and under the protection of the British police for 9 years, his humor did not perish, nor did his strength of mind. Rushdie continued to write and was not a whit careful or wiser for having a bounty on his head or having been forced to grow a sense of death.

Could it have been different–“the “Rushdie Affair,” as it was called in the mid-90s when Rushdie’s Satanic Verses (1988) was banned in India, Pakistan, and several other countries soon after its publication, and vociferously protested in several countries. It is time to go beyond looking at but rather the time to look through the glass of the “Rushdie Affair,” as Mukul Kesavan’s brilliant novel Looking Through Glass (from which I borrow part of the title of this essay) does in his novel in relation to the Quit India Movement by exploring what agency or action can mean for a non-separatist Muslim-Indian in relation to the 1942 Quit India Movement. It is time to seek to understand the patterns and the paradigm of the “Rushdie Affair” for those concerned with the fabric of democratic nations.

How did Khomeini’s fatwa-a sentence by one political leader in in one country- become so inexorably powerful? What were the different forces operating on the liberal and the Islamic side of the “Rushdie Affair” that made it so violent? The “Rushdie Affair” 30 years ago was characterized by dangerous non-reading on both sides of the support for and the wrath against Rushdie and this non-reading or canceling the discourse of the other side is at the heart of the murderous division, hostility, and the repetitive description of the goodness of one’s own side.

The ghost from the first episode of “Rushdie Affair” has returned 33 years later and the effects are more horrifying. The emptying of any possibility of communication is what violence does. This essay seeks to look at the structural violence of that 3 decade-old zero-sum-game of hostility.

What we are told again and again, and what we know is that Muslims were gravely offended by The Satanic Verses, believing it to constitute defamation and an insult to Islam, and even those who did not take to streets opposed Rushdie’s novel. But what we were not told is the diversity and difference within the Muslim response to Khomeini’s fatwa and to the Satanic Verses crisis. MM Slaughter’s excellent essay, “The Rushdie Affair: Apostasy, Honor, and the Freedom of Speech” traces the diversity of responses within the Muslim response and argues that this difference cannot be voided: “while fundamentalists in Iran and England and some other places welcomed Aytollah’s fatwa, most Muslims considered the fatwa on Rushdie’s head as a terroristic act and not as an issue of free speech, and that most Muslims rejected Khomeini’s fatwa as an example of Shiite or Iranian fanaticism.”

There was indifference not only to the Muslim support for Rushdie and to the diversity of response within the Muslim public sphere, the Western liberal support for Satanic Verses was accorded the univocal dominant role in the rescue of a heroically blasphemous Rushdie. The support was not unanimous, by any means, even among writers. John Le Carre, for example, wrote in The Guardian, “there is no law in life or nature that says great religions may be insulted with impunity.”

How has liberalism’s support for Salman Rushdie changed or morphed since the 90s, and how has liberalism itself changed in the intervening years? Tracing the ‘then and now’ of the liberal support and the silencing of the Muslim support for Rushdie is what this essay seeks to explore. But to do that I must provide some background of Satanic Verses crisis as it emerged in the 90s, especially in Britain.

Satanic Verses is about Muslim migrants to Britain, the migrant’s dream of survival and its metamorphosis. This migration or “relocation” or “cultural severance,” in Homi Bhabha’s words form “a dangerous tryst with the untranslatable” that creates “the gap between the verse and the meaning” is connected to the early days of Islam in Jahilia within the novel’s comic vision.

The “Rushdie Affair” battlelines began in Britain months before the declaration of Khomeini’s fatwa. Then Khomeinism and his fatwa took it to another level.

A video from 1996 that has surfaced on Youtube under title “Salman Rushdie Fatwa! Shocking Muslim Belief! Must Watch” reveals something else altogether, an Imam telling British journalists that Khoemini’s fatwa does not have any authority to punish blasphemy or Rushdie, and by using the influence of Mujtahids and by using the Hadith and the Quran, the fatwa, can be most productively rebutted. He also says that he is sure that this interview will not be printed in the British Press because the “the only story you want flashing on the front page of your papers is that of Khomeinism as the face of Islam.” This is how, as Gayatri Spivak puts it, Ayatollah Khomeini became the “author-function” of the novel.

The “fatwa” acquired such a proverbial status in the Western press that it became a passing invocation that needed no further elaboration, a code-word that described the shocking Muslim response to the novel, indeed, a quintessential Muslim response to anything modern.

When I was writing my PhD dissertation on the “Rushdie Affair,” the breakthrough came when I found the book: For Rushdie: Essays by Arab and Muslim Writers in Defense of Free Speech. The Publisher’s Note said: “A collection of texts by Arab and Muslim writers expressing support for Salman Rushdie’s novel Satanic Verses.” Some of the essays were focused on a denunciation of the violence of religious extremism, and some specifically on Khomeini’s fatwa, which was framed within a historical context of its production : the Sunni-Shia conflict and Iran’s opportunity to extend the territory of Shia influence with the fatwa declaration, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s (the Shah’s) campaign for Americanization, the atrocities of the SAVAK, and Ayatollah’s strategic return from exile in 1977 (satirically described in the London section of the Rushdie’s Satanic Verses). Most notable was the essay by Ayatollah Gandhjeih, who observes that it is not Rushdie’s Satanic Verses that is blasphemous but Khomeini’s fatwa, which is a “blanket order for collective murder.” In Ayatollah Gandhejeih’s words, “by addressing himself to fanatical populist elements, who had already been shamelessly manipulated, Khomeini succeeded in bringing the religious beliefs of Muslims into even greater disrepute” (150). Ayatollah Gandhjeih’s concern is to show that Khomeini’s fatwa “is a political maneuver that blasphemously uses religion to mask the contradictions of his regime and create an international crisis so that he can divert attention from its innumerable problems . . . following the bitter defeat by Iraq” (1988). He quotes the text of the fatwa to show how deliberately blurring it is: “The fuzziness of the sentence gives no precise details about the identity or nationality of people condemned by this document, and this cannot be missed by anyone who is knowledgeable in Islamic jurisprudence.”

Although “Iran” is what we keep circling back to in any discussion of the “Rushdie Affair, Iran was not the first arena of the Muslim protest the novel. India banned the book within 10 days of publication with Syed Shahabuddin’s (MP, Janatha Dal) letter to Rushdie in Times of India soon after the publication of the novel in September 1998. Then Shabbir Akhtar of the Bradford Council of Mosques in England, within 2 months of publication of the novel, went on the offensive by calling on Muslims “to either take offense at the novel or ipso facto cease to be Muslims.”

The Satanic Verses and the Britain connection was dominated by the “Bradford Book-Burning Event” in which a group of Bradford Muslims from Mirpur, on the advice of a lawyer, burnt copies of the book on 14 January 1989 to bring attention to their sense of injury and their failed attempts to seek apology from the publishers or to seek redress from Britain’s blasphemy law (which has been repealed only as recently as 2021). As Yunus Samad shows in his essay, Book Burning and Race Relations: The Political Mobilisation of Bradford Muslims, the act of book-burning doomed their hope of drawing attention to their grievances because it precipitated, “a national hysteria as it evoked memories of the Nazi-burning of books.” As Talal Asad in his Genealogies of Religion points out “Britain has witnessed innumerable angry demonstrations before, by anti-racists, fascists, by feminists and gays, by abortion-rights activists, trade-unionists, students, and major urban riots in Nottingham, Brixton, Birmingham, Liverpool etc., but the Bradford Book Burning Affair is perceived as the ultimate marker in racial-cultural difference even though it was not a law-and-order problem but rather the political mobilisation of a religious tradition that has no place in the cultural hegemony of British and was therefore a symbolic threat to the essential character of Britishness.” The Bradford Book-Burning event brought to surface not only panic about immigration, but it also escalated, in Bhikhu Parekh’s words, “step by even sillier step to a wholly mindless anger first against all Bradford Muslims, then against all Muslims, and ultimately against Islam itself.”

The Western legacy of dissent and imagination threatened by the forces of Muslim fundamentalism produced a jingoistic nationalism. Even Britons who considered themselves tolerant and who earlier might have regarded the visible minority of British Muslims only with scorn and apprehension, when confronted with the anti-Rushdie protests, now replaced it with contempt.

The “Rushdie Affair” transformed the stereotype of the “Paki immigrant” into that of the “Muslim fundamentalist” and was “used to reinforce a whole range of anti-Asian jokes: Tee-Shirts like I am Salman Rushdie and jokes about forthcoming novels titled, Buddha, You Fat Fuck.” Racist attitudes against British Muslims hardened. Meanwhile, Rushdie caught between his liberal supporters (about whom he must have felt the cringe of “with-friends-like-this”) and the protesting Bradford Muslims could only say: “I did not invent British racism, nor did Satanic Verses. The Commission for Racial Equality which now accuses me of harming race-relations, knows that for years it lent out my taped anti-racist Channel 4 broadcasts. I have never given the least comfort or encouragement to racists, but the leaders of the campaign against me have reinforced the worst stereotypes of Muslims as repressive, anti-liberal, censoring zealots.”

Rushdie, the embattled writer and scholar under threat from violence, was reconstructed in the media as a quintessentially English hero. Tony Harrison’s Blasphemer’s Banquet which aired on Channel 4 placed Rushdie within the canonical tradition of dissent and transgression held up by Voltaire, Blake, Moliere, and Byron. The beleaguered tone of this sentiment was heard in these lines of William Blake used in Blasphemer’s Banquet: “I shall not cease from mental strife/nor shall my pen sleep in my hand/till Rushdie has a right to life/and books are not burnt.”

Even though many, many Muslim scholars, writers, Mujtahids and secular Muslims were active in defending Rushdie and in rebutting Ayatollah Khomeini’s blanket order for murder, their engagement was not invited, nor it did it make news.

The core discriminations within liberalism-against people of colonial origin and against faith or religion-found their most vehement expression in the “Rushdie-Affair”

Blasphemy, within the liberal support for Rushdie made its appearance as that which stands for the spirit of literary imagination. Freedom of imagination was the language of the liberal support for Rushdie in the 90s, as freedom of speech is the language of support for Rushdie today. Maybe, freedom of imagination is regarded as snobbish, as we join in the march for free speech.

The inward freedom represented by imagination as it is gathered in the Western literary tradition is what the blasphemy of Satanic Verses was as seen as boldly holding up. The same imagination that Wordsworth asserts in The Prelude as “another name for absolute power/And clearest insight, amplitude of mind/And reason in her most exalted mood” or the one Shelley defines as “the great instrument of moral good!” Within this logic, the “blasphemy” of Satanic Verses emerged as the heroic agency of the author in the face of the dogmatic and fanatical authority.

This notion of a transcendent individualism is natural to liberalism, particularly to Western liberalism, and arises from its central belief in the liberty of the individual and its sense that society is an aggregate of individuals, rather than a community.

Michael Ignatieff put it like this: “Where we waver in in our resolve to defend crucial freedoms, we are always joining the mob.”

The “mob” is represented by Hadi Matar, a Lebanese American from Fairview New Jersey, who said he read only 2 pages of the 546 page novel and was surprised that Rushdie survived the attack. If this were a play, and we were theatergoers watching Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice or Webster’s White Devil, just from viewing the knife held mid-air, we could imagine the full horror of this stabbing: the knife through the skin, the sluiced veins, the damaged nerves, and organs. And the blood! Andrew Wylie, Rushdie’s agent, has said that Rushdie’s injuries are severe, and he will probably be blind in one eye.

This attack and violence as censorship is to be condemned in the strongest possible terms.

Also, alarming was the lack of security at the Chautauqua Institution in New York where Rushdie was to speak about the US as an asylum for writers of politically edgy satire. Since Rushdie did not like police-presence at his events, there was no security, no checking of guests at the entrance. A doctor happened to be on the scene, and Rushdie was air-lifted to the local hospital.

Defying the odds, that’s ‘our’ Rushdie!

May he recover his health soon, and write another comic, satirical best-seller.

Hadi Matar seems to be a ghost from the previous episode of the “Rushdie Affair,” and also a character come alive from the pages of Satanic Verses the ghost of the rejected, abject character, Saladin Chamcha, who at one time was an upper-class gentleman with a “sacred passion for the Royal Family, Cricket, The Houses of Parliament” who is now turned into an allegory of the “Paki immigrant” after he is tortured by the police, and becomes the very type of the visibly “minority immigrant” he had so insistently distanced himself from in the past, the “satyr-cal,” monstrous double of proper British citizen as defined in Thatcherite Britain of the 80s along racial lines.

When Rushdie moved from London to New York city in 1999, and the fatwa was officially lifted by the Iranian Government, finally, it seemed that Rushdie had shaken off the fatwa corpse off his back. As a New Yorker, Rushdie witnessed the death and destruction of Sept 11th, and his own experience earned him the authority to become a commentator on Islamic terrorism, and he also become a champion of freedom of speech. In New York, Rushdie was able to live to the full the life and fortune of a celebrity-writer and live like a superman among writers (while the icons of Superman and Batman were themselves becoming alarmingly human). In an interview, Rushdie speaks of how finally Satanic Verses was finally leading “the ordinary life of a novel, being read, being liked or not liked, and people were finally able see how funny it is and not just anti-religious.”

Rushdie is right about the comedy of the novel. The genre of the Satanic Verses changed in the aftermath of the “Rushdie Affair” so violently into non-fiction that for both sides, it became an exercise in forensic pathology. Where are the secrets located? Where is the blasphemy located?

If the fate of Nabokov’s Lolita represents one end of the death of the novel, Satanic Verses represents the other end.

But the novel itself, while it remains unread if purchased on both the liberal and the Muslim side for radically opposed reasons, Satanic Verses is a quintessentially South-Asian novel, a post-colonial novel, for its humor alone.

As Sara Suleri put it in her essay, Whither Rushdie, “As a mere crusade against the intransigence of Islam, the Verses would not be interesting at all; the text’s impelling significance inheres instead in its ability to question and to recast the repercussions of ‘”exile” in the idiom of postcolonialism.” Suleri reads Rushdie’s so-called “blasphemy” as “a gesture of wrenching loyalty that chooses disloyalty in order to dramatize its continuing obsession with the metaphors that Islam makes available to a postcolonial sensibility.”

Suleri’s handling of the notion of blasphemy allows for its derivation from the cultural context of secular Muslim identity rather than as inevitably belonging to a Western secular consciousness. The most nuanced essays on Satanic Verses have been written by postcolonial or South Asian writers: Sara Suleri, Feroza Juzzawala, Homi Bhabha, Gayatri Spivak, Aamir Mufti, Srinivas Aravamudan, and others.

Aamir Mufti in “Reading the “Rushdie Affair” shows that while the “liberal shock” at the Muslim refusal to read the novel dominates the rhetorical context of the “Rushdie Affair,” the liberal reading of the novel also operated within philistine pop-cultural forms of reading. But this much vaunted shock conceals the liberal non-reading. The condescending ease with which the liberal support for Rushdie claimed for itself the rigor and seriousness of real reading while the Muslim response to the novel was categorized as philistine, backward, fanatic and shocking has to do with liberalism’s ability to inflate their “goodness” to maximum advantage. In this new 2022 phase of the “Rushdie Affair,” on September 16th Friday, PEN American and New York Public Library will be hosting a reading from the Satanic Verses and those unable to attend the “Stand with Salman” event can read passages from the novel and share it as a video.

It is not what the liberal support for Rushdie has affirmed that I have a problem with, it is what it has left out. Everybody agrees it is about free speech. I am all for free speech. But saying free speech does not change the reality that free speech is always in tension with force or violence or purveyors of violence. Free speech is not free. Rushdie has paid the price. Reading Satanic Verses is more important. Rushdie is an easy bandwagon to get on. Satanic Verses is a novel that asks to be read with care because it epitomizes, in Suleri’s words, “the urgent cultural fidelity represented by specific acts of religious betrayal.” The novel, like good fiction does, shows the implicatedness of goodness with non-goodness, of faith with doubt, of loyalty with disloyalty to do away with false pieties and political perversions of religion to show what absence of faith can do to a human being.

“Read dangerously” is the motto of Conjunctions, a journal of contemporary writing I read occasionally, and the title also of Azar Nafisi’s book of essays, the author of Reading Lolita in Tehran. As mottos go, it is admirable and trendy. It suggests that we should read fearlessly. Perhaps, what it also suggests is that we must ‘read subversively, transgressively.’ I quibble with the subjectiveness of the suggestion, also with the directiveness and the sense that a book must be confronted rather than actively read or listened to or faced! The first act of reading, it seems to me, is simply attentiveness.

If there is something worse than reading dangerously, it is ‘non-Reading dangerously’ and that can be said, fundamentally, to encapsulate the “Rushdie Affair.” And that is why the ‘sentence’-or “the longest public execution” could not be shaken off.

And Rushdie has encountered it once again 33 years later on the stage at the Chautauqua Institution in New York, in the form of the knife-wielding Hadi Matar.

Free speech is easy to say but doing it has a full cost to attached to it. Invoking it as a rhetorical slogan and deactivating it of context, is an artifice, a slogan.

What if there was not such vainglorious non-reading on both sides of the conflict? What if instead of a lazy reliance on abstractions like free-speech and blasphemy, there was some curiosity about the more than that meets the eye in the different responses ranging from rage to anger to a sense of injury to support for Rushdie within the Muslim public sphere?

The truth is that liberalism today seems to have internalized its own version of the punitive blasphemy law in many ways. Not only do they censor and cancel people for expressing opinions they do not like, today’s liberals also increasingly direct what we read, what we say, what we hear and what we should not read or hear. They organize, consolidate, and manipulate to cancel people. They tip the scales, stack the deck, and champion their own fairness. The liberals are the ones who are far too certain about their goodness now. Rushdie’s Satanic Verses asks to be read for this constant tussle between certainty and doubt, not just supported.

The words of Rowan Williams, the current Archbishop of Canterbury, remind us “not to segregate goodness from reality.”

The good are those who don’t always like to see what they are implicated in. And that can blind us to how we are shaped by what we do not know. Simply to focus on goodness can be a problem.

Rowan Williams, the Archbishop of Canterbury, speaking about Marylinn Robinson’s Gilead

******

Padma Challakere teaches high-school English in St.Paul, MN. She has taught literature and writing in liberal arts colleges in Minnesota for two decades. In the last few years, she has published essays in Counter Punch, The Hindu, The Deccan Herald, and The Wire on topics such as the Afghanistan war novel, Ustad Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Kishori Amonkar, V.S Naipaul, and Bret Easton Ellis.

Padmaja Challakere in The Beacon

“The looking glass” has significantly magnified the current global issues of fundamentalism. I really love that part where you talk about “non-reading” of the other side which gravely contributes to conflicts. And, a thorough review of the “Rushdie Affair”! No wonder, it has been the topic for your research previously. No “Rush” for Salman to “die”, May he live on!

Congratulations ma’am, for one more engaging and brilliant write up!