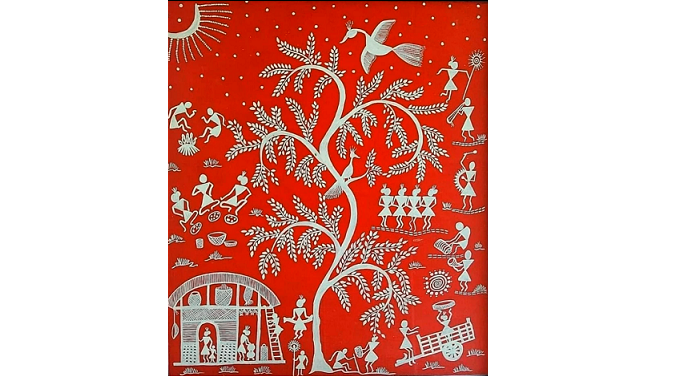

Tree of Life. Warli painting

Asif Raza

I

n her talk with the renowned poet Pat Matsueda, A Conservationist’s Palette: Melissa Chimera Talks with Pat Matsueda, Melissa Chimera, artist and environment activist cites the example of social paradigm shifts in our time (such as the civil rights movement, gay marriages, and the youth climate strike) and poses the question: “Is our prevailing human-centered perspective the only reality?”.

My comments below are an attempt, howsoever sketchy or faltering, to address that question.

The Norwegian philosopher, Arne Naess, was the first to mount a challenge to the traditional ecological perspective alluded to by the artist in her conversation cited above. Since he believed the prevailing human-centered perspective betrayed a lack of depth in understanding the ecosystem, he labeled it “shallow ecology“. and in 1972, put forward his ecological vision which he called “deep ecology” (or ecosophy wherein he laid down the precepts and principles of deep ecology.)

Deep ecology still stands its ground as the most influential ecological paradigm in the contemporary world (despite its distractors and their charges that it encourages “ecofascism”).

“Oh, East is East and West is West, and never the twain shall meet,” Kipling had famously proclaimed in his “The Ballad of East and West” However, one finds it spiritually uplifting to see the twain meet— in deep ecology, the twain being Naess, from the West, and Mahatma Gandhi from the East.

Mahatma Gandhi’s influence on Naess’ environmental writings, with its emphasis on ecological harmony between human and nonhuman entities, cannot be overstated.

Gandhi had gleaned his non-dualist philosophy from the Bhagavat Gita. The Gita concedes intrinsic value to nature, rather than merely an instrumental one of fulfilling only human needs. This vision is the pivot on which Naess’ ecosophy turns.

All deep ecologists following in Naess’ footsteps have rejected shallow ecology and have adhered to the same Gandhian vision that celebrates the oneness of all living and nonliving entities. They criticize shallow ecology for being anthropocentric and non-inclusionary, and for setting up human and nonhuman life as binaries in which the former has ascendency over the latter.

Naess followed Mahatma Gandhi not only in “theory” but also in his “praxis” that is, his social activism was entirely predicated on Gandhi’s political ethics of nonviolence.

Also Read Arne Naess and Deep Ecology: Gandhi’s Profound Influence on its Evolution.

Interestingly, there is another example of a seminal philosopher of the 20th century from the West, namely Martin Heidegger coming to drink, late in his philosophical career, at the fountains of Eastern mysticism, specifically Mahayana Buddhism and Taoism. In doing so, he ended up buttressing the core principles of deep ecology even though his lifelong pursuit was and remained his being-centered ontology and never ecology per se. His life goal was not to marshal support against species extinction, saving the planet, or environmental destruction but to reinstate the forgotten being at the center of western philosophy, a topic that is best avoided here in the interest of not dragging the reader along the thorny path of stiff philosophical jargon. Yet his phenomenological ontology of Being provided deep ecologists with scaffolding for their ecological views.

From the perspective of deep ecologists, the most significant aspect of his phenomenological ontology was its departure from Western analytical thought and, under the influence of Mahayana Buddhism and Taoism, his rejection of dualistic thinking, and simplistic subject-object opposition. It is from this perspective that sprang his brutal critique of Western technology and Modernity. He emphasized the interconnectedness of humans with the nonhuman world and underscored the importance of addressing the needs of both human and nonhuman life.

He single-handedly deconstructed the western metaphysical paradigm that had reigned over philosophy for more than two millennia, blaming it for the dominance of technocratic-utilitarian ethos in western culture, a culture whose calculative rationalism promotes homocentric, dualist views and treatment of nature just as a vast reservoir of resources for systematic extraction and unabated appropriation without conceding it any inherent value. In this way, rejecting, Western analytical thought, he postulates a non-anthropocentric being-centered ontology and advances the Taoist notion of “letting things be”.

More than two decades after its enunciation, Naess presented a reformulation of the salient precepts of deep ecology, based among others, on Buddhist, Taoist, and Heideggerian principles.

******

Asif Raza is an Urdu poet and translates many of them into English. He lives in Tyler, Texas, USA.

Asif Raza in The Beacon

Thank you Asif for raising these important sources of non-human centered thinking across many cultures and many times–or as a colleague of mine once described, that the line between human and nature is pretty blurred among native peoples. I’m always reminded it didn’t exist then, and science tells us that it doesn’t exist now. And any ecological movement that aims to take people out of the equation is in itself an artificial and recent phenomenon, one in contrast to non-dual world view traditionally held in high regard among native peoples for a very long time.