gallerist.in

M. Nandakumar.

(Translated from Malayalam by Aadya Sain)

A

fter two months of being transferred to this city branch, I met my other. He came to open a new bank account last summer. A quiet afternoon. When he filled out the form, I found out that we shared the same name. I’m A. Sudhakaran; he’s M. Sudhakaran. Just a difference in the initials. He laughed aloud when I mentioned it. Hearing his laughter, the employees and some clients stared at us.

Upon seeing the ‘Silence’ board, he lowered his voice and said: “But initial is an important difference.”

M Sudhakaran is eight years older than me. Against the occupation column, he wrote ‘sales executive’. I inquired what he was selling.

“Encyclopedias, dictionaries, general knowledge…are you interested?”

Since there was no chance for me to write any public exams, I shook my head.

“Since you’re my other, I’ll give you a discount; just pay half the price”, he laughed in a low voice. I dodged him by saying I would consider the offer. By afternoon, the word ‘other’ had crept into my mind.

I lived on the third-floor of the Metro Plaza tourist home and had my meals from the hotel downstairs. It was nearly half an hour’s walk to the bank and back in the morning and evening. Twilights were spent on the seashore. Once in a while in the theatres. That was my daily routine in those days. Three employees from the bank also lived in the same Metro Plaza. They were my first acquaintances in this town. Since I was not an expert in playing card games with naughty bachelors, joining in Sunday alcohol parties or sharing spicy jokes, our friendship was limited to greetings.

I didn’t feel any particular closeness or distance towards the world I saw from the third-floor veranda.

One evening, I saw M. Sudhakaran again on my walk along the seashore. He was carrying a big cloth bag filled with thick books. He waved his hand upon seeing me from a distance.

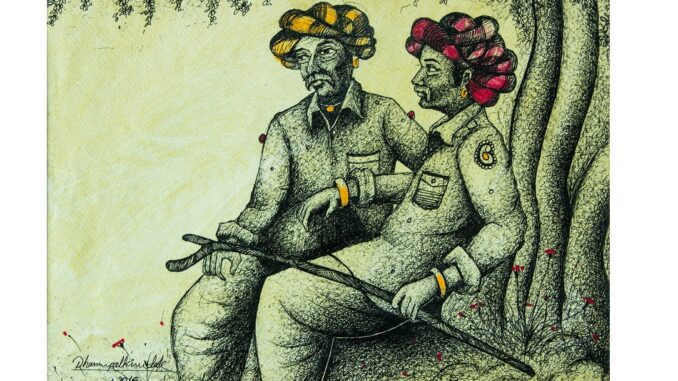

M walked along the frothy fringe of the waves, wetting his feet. Although he stooped a little, I noticed that my other was taller than me, around six feet. His long face, grizzled beard, and forehead seemed wider since he was fast balding. He yelled while dragging his feet in the sand:

“Hello, other…”

We sat on the pedestal of one of the many statues on the beach, enjoying the evening sea breeze after a hot day.

“How were sales today?” I asked.

“It was quite okay. Sold an Oxford dictionary and two Rapidex Spoken English coursebooks.” M was excited.

Maybe because we shared the same name, the awkwardness between us slowly disappeared. M summed up his life in that intimacy as the waves brought some debris to the shore in the twilight.

M was born, brought up, and educated in this town. After earning a postgraduate degree in economics, he set off for Bombay. Just like many others in the 70s. After a series of odd jobs, he got into a share trading consultancy in Andheri, which was not a bad job and with a fair salary. Along with his work, he published a series of articles in a weekly magazine on instances of fraud and scams in the stock market, with evidence. The encouragement of a journalist friend was the inspiration for this article. He was fired from the consultancy before the series was completed. As if that was not enough, he was framed by the firm and put behind bars. It was the emergency period. Just because that journalist friend had connections with higher officials, his life was not in danger. After six months of imprisonment, he came back to his hometown.

“Hot peanuts…hot peanuts…,”

A scrawny Tamil girl came to us with a basket. “Sir, please buy some….”

M bought two packs of peanuts.

“Shouldn’t we have some hot nuts to crack while reminiscing?”

I munched the peanuts while listening to my other recounting his experiences.

Upon reaching M’s hometown, he worked as a manager in the Basel Mission’s tile company for some time. It was then that he fell in love for the first time.

“Rema was a clerk in the company’s finance department. Both of our parents were against us. Caste issues. We bought some utensils and furniture and rented a house near the tile company. That was all.”

“What about kids?”

“No kids…she left me before any materialised.”

I was stunned for a moment by his cool indifference. “Then what did you do?”

“What can I do? She was soon tired of me. Isn’t this common with humans?” M’s laughter blended with the roaring voice of the sea.

The night Rema revealed that she was in love with another man, M. Sudhakaran lay down thinking.

“Who’s he?” M asked calmly.

He knew the man—a youngster who works at a saree shop on court road.

The next day, M arranged a rented house for them. He moved the utensils, furniture, and television to their new location in a box cart. He no longer needed them. While handing some money to Rema, he consoled her:

“He may not have much salary. Inform me when the money is tight. I’ll help you as best I can.” That’s when Rema broke down for real.

“You never loved me.”

M smiled: “That’s where you are wrong.”

M left the tile company after his divorce. He wandered as a medical representative in many places. His current job was selling words and knowledge.

M Sudhakaran inquired about A. Sudhakaran’s news.

What I have to describe was a mediocre life. My homeland was on the district’s border, about 300 kilometres away. Parents are retired teachers, and a homemaker sister with her family. My wife, Lathika, works in a school as a Maths teacher. Two-year-old son Jithu. Regular phone calls to home and occasional visits whenever two or three holidays come in a row. Nothing more.

The darkness that began from the horizon traversed across the vast waters and slowly enveloped the coastal town. People and their shadows gradually decreased. As I stared at the waves in the light of the distant boats, I could not get a grip on the mind of my other. After bidding farewell, I walked aiming at the Metro Plaza while thoughts about him drifted in strange directions.

Days later, I saw M. Sudhakaran in front of a procession to the collectorate. He was raising slogans against Vasco da Gama and the Department of Culture. I had also read the news that the government had decided to name the beach where Gama was supposed to have landed by his name.

When the protest march dispersed, we went to a tea shop near the town hall.

He had left the bookselling job because it was not profitable. He was looking for a new job and had recently taken up photography with an old Canon camera. Some evening newspapers had agreed to publish his photographs.

“There’s no point in doing anything, so let’s try everything.”

The moral of his lesson was to face life without any hint of failure or disappointment. What exactly was it? Can a permanent bank employee like myself understand?

M occasionally visited my room in the Metro Plaza to talk about politics, literature, and global events. My familiar perceptions were confused when he viewed the matters from the other side. I began to forget the contents of the books I had read in college. I have no particular politics beyond the frown I have when I see the newspaper and the TV. The headaches gifted by the newly installed ERP software on the bank’s computer network, mother’s rheumatoid arthritis, Lathika’s staffroom gossip, Jithu’s phrases that do not exist in any language… They were enough to make my world eventful.

My only luxury was the happiness of eating the chicken biriyani from Hilda’s Hut, run by an Anglo-Indian lady in Francis Lane (even though the amount of fennel was too much in the masala). Somewhere in between this, M’s ephemeral attracted me. His rebellious denunciations had the potential to destroy my boredom.

That’s how I started to visit the public library and art gallery exhibitions with M. Sudhakaran.

Even though I met some of his friends, I preferred to sit alone under the Gulmohar tree.

On a Sunday, M took me to watch a play staged in the town hall. He booked our tickets. The theme was an adaptation of a French play in which the people of an area are entirely transformed into rhinoceroses to indicate the spread of totalitarianism. I was enjoying the novelty of the stage, the setting of light and sound, and the liveliness of the actors. Suddenly, I heard some noise from the back row.

“Ayyo…snake…snake…I think it bit me…it’s a cobra…somebody please help!”

The play was disrupted. We rushed out through the tumbling chairs. As we walked through the back alley of the army camp, M explained the essence of the play to me; about the willpower of the alcoholic protagonist of the play to remain as a human when everyone else turns into a rhinoceros.

“We all have grown horns, dear fellow….”

On the way, M revealed the reality behind the cobra incident. The snake had been bought and brought down by those who had quarreled and left the theatre troupe playing that day. The troupe was split because of differences in opinion.

“The opposition group is staging this same play differently next month. Let’s go and watch that too.”

M Sudharakaran’s savings account was not particularly beneficial or harmful to the branch. Occasionally he came to withdraw cash from the ATM in front of the bank. Small amounts were received for non-retail transactions. Meanwhile, about Rs 20,000 was deposited into his account. That evening M came to celebrate at the Metro Plaza with half a bottle of whiskey.

“You appear to have struck gold.”

One of the well-wishers of M. Sudhakaran had decided to make a film. The project originated under the mango tree in the public library. M should write the story and screenplay.

“What’s the story?”

“It’s our misconception that a film needs a story.”

He poured out the second peg and began to shape his ideas.

“Our city, its streets, people, and the sights…that’s the story. Jewellery shops and waste heaps should be shown in adjacent shots. Also, the overbridges and the streets where wooden furniture is sold, twice-weekly ships that sail towards the island. Then parks, bars, zoos, the dirt, the flow, and that one man who walks through it all. I have to figure out what his life will be like. The advance for that trouble is these twenty thousand rupees.”

“Isn’t this your story?” I doubted.

“Hahaha… then what about imagining the life of A. Sudhakaran? There’s nothing fresh in my life. Nothing interests me.”

Maybe because of the screenplay writing, I didn’t see M for some days. Summer and monsoon have passed, and now it’s the Onam vacation. I, Lathika and Jithu visited Shimla and Manali with the bank’s family package. Sparse pine forests in the Himalayan valleys, buildings and railways which are colonial monuments, a temple of goddess Kali, Taradevi hill, molten silver like mountain peaks, River Beas which flows through the valleys of Kullu, apple orchards… Lathika recorded everything she saw with her camera. Even before reaching home from the tour, Jithu caught a cough and fever.

Thus, the vacation came to an end. After returning to the city and getting my room key back from the receptionist in the Metro Plaza, she informed me:

“Someone called here asking for you after you left for your home town two days ago.” “What’s the matter?”

“They thought you got into an accident. I informed them that you’re okay and had left for your home town.”

“That’s right. The only accident that happened was my going home.”

I began looking for M. Sudhakaran’s phone number. My guess that someone had mistaken him for me was correct. M was bedridden with a broken leg. A drunk biker hit him and left without looking back. The accident had occurred on the street towards the lodge.

I know he was staying at the Burma Lodge close to the railway station. Even though I had known him for months, I had never visited his lodge. He had never invited me.

Lathika had given me chutney powder, fried banana and yam chips in separate packets for my ‘other’. I put them in a plastic bag and walked to the railway station.

I arrived at the Burma Lodge, squashed in a maze among workshops and shops selling automobile spare parts. Burma Lodge had been in existence since the city’s inception. Freight lorries were parked in front of the building.

M Sudhakaran lay on a rope bed under the rotten roof supported by ancient pillars. He tried to get up when he saw me. The fat man in the chair beside him gently propped up M against the wall.

“This has been my palace for ages,” he says, his deep laugh unaffected.

His right leg was in a plaster cast all the way up to his knee. Some of his ribs on both sides are broken. Stitching and plastering were done in the government hospital. One and a half months of bed rest was needed for a full recovery.

“What about the cinema?”

“A cooker betrayed me,” he couldn’t laugh as heartily because of the pain in the ribs.

M had met with the Director to discuss the screenplay’s progress. An old ancestral house in the middle of a coconut grove was rented for the film’s production. The discussion was fruitless. The storyline’s discontinuity and irrationality were the issues. M contended that the world is not so logical. The director was displeased. After purchasing fish, vegetables, and liquor, they decided to continue the debate.

“You prepare the rice by the time I return. I’ll prepare sambar and fish fry.”

After measuring out the hard-to-cook matta rice and giving the rice cooker to him, the director went to the market. M washed the rice three or four times and put it in the cooker with a reasonable amount of water. But, the lid of that Prestige cooker was confusing. No matter how many times he tried, the lid was not closing properly.

M was still struggling with the cooker when the director returned with half a kilogram of sardine, sambar pieces and rum.

The director yelled: “Don’t write the story for my film if you don’t even know how to put on the lid of a cooker.”

M winked at me, saying it was a relief that the director hadn’t demanded the refund money yet. “I didn’t have to beg people for money to pay the hospital bill because of that money.”

The fat man who sat next to M lit his next beedi. He was trying to tune into the Ceylon station on his pocket radio. Mukesh’s love song floated out through the static of the radio.

I took a look around. Ten or twelve cots were strewn across the shattered floor with stained bedclothes and pillows. The clothes on the hangers were faded. Broken buckets were stored beneath the cots. In the corner of the room, an old man sat down to light the kerosene stove. Another man folded and pressed the clothes under the bed to make them appear ironed.

M introduced the fat man. He was a lottery seller on the train; now, helped M to the bathroom and hospital. Street vendors and long-distance truck drivers stop for a rest. The cost of the beds is fifteen rupees per night. That is Burma Lodge.

“This small bed is more than enough for me. I have the city during the day. A place to sleep when the sun goes down. Tea and snacks from the Burma canteen. Since it’s been fifteen years, I only have to pay now and then. The Seth was a friend of my father in Burma.”

I placed the snacks sent by Lathika on a three-legged table near the wall. M asked about the new words Jithu had learned lately.

“Kammachi, which means Kanmashi- the kajal. Pownder, which means powder. He can say pappadam without a mistake.”

“My Onam this year became like this…but it’s okay.” M sighed. I sat there without any topics to discuss.

“I got a translation work.” M became excited. “Economic papers and philosophical essays of Karl Marx written in 1844. It’s a superb collection. The publisher gave this to me, knowing I hold a postgraduate degree in economics. My interest is in the rebellious tones of love in them. The alienation of man from the products made by him, the work, nature, fellow beings…and the rage about each human being moving away from themselves, as well as the great empathy, felt for the human condition….”

“I’m likely to finish this job.” M didn’t laugh.

We didn’t talk about anything for a while. The electric lamp lit by someone had a depressing brightness. The shadows of the hanging clothes fell on the plaster-peeled wall. M appeared to be an older man all of a sudden. His long white beard, baldness, and stooped posture contributed to his appearance. He may now be the same height as me.

M asked the lottery seller to take the leather box under the bed and put it on the table. He opened the box by pressing the metal locks on each side. He took a thin book from the bundle of shirts and pants.

“These are the poems I wrote. They were published when I was young. Only two hundred copies were printed. It’s not currently available. I didn’t write any further; I couldn’t.”

M took a Parker pen from a chamber from the lid of the box. He slowly opened the book.

Under the space where the heading ‘A User Manual for Losers’ and his name printed even smaller as M. Sudhakaran, he wrote carefully in neat blue handwriting:

To my other, With love, M

He signed like an ECG graph.

“I’ve two copies with me. You can have one.” I took the book.

“OK then, I’m leaving. I’ll come again tomorrow.”

“No need… I’ve got these people. When I can walk, I’ll come by your room.”

When I stood up, M said out of nowhere: “I saw Rema. She has two kids now. They’ve grown well.” He suddenly stopped.

As I walked out of Burma Lodge through the corridors of the mortuary of vehicles, I believed that I understood M. I got the difference in our initials. From now on, our meetings will be cut short like one of those long-forgotten friendships.

I called Lathika after reaching my room in Metro Plaza. Jithu’s fever subsided.

I started to go through the ‘A User Manual for Losers’ from the veranda of the third floor. Usually, I don’t read poems. It’s a foreign realm for me.

There were only a few lines in his last poem: “A traveler is destined to die on the road

But I am dying instead of you Only for you.”

I closed the book and shut my door against the night outside.

********

Nandakumar has penned various works of fiction including Vayillakkunnilappan (A Mouthless God- Stories), Kathakal (Stories), Nilavilikkunnilekkulla Kayattam (Ascending the Hill of Scream-Novella), Kalidasante Maranam (Death of Kalidasa-Novel), Nashtakkanakkukarkku Oru Jeevitha Sahayi (A User Manual for Losers-Stories), Chennai: Vazhithettiyavarude Yathravivaranam (Chennai: Travelogue by those who lost their ways- poems), Neerenkal Cheppedukal (Novel) and co-authored Pranayam: 1024 Kurukkuvazhikal (Love: 1024 shortcuts- Novel) with G. S. Subha. ‘Chithrasoothram’ (Image Threads), a film directed by Vipin Vijay, is based on the novella ‘Varthali: Cyber Spaceil Oru Pranaya Nadakam’ (Varthali: A Love Play in Cyberspace). The movie bagged national and state awards for sound and camera and also a special jury mention for the director. The short story “A User Manual for Losers” was published in Mathrubhumi Weekly under the title Nashtakkanakkukarkku Oru Jeevitha Sahayi. Nandakumar hails from Palakkad in Kerala, completed B.Tech from Palakkad NSS Engineering College, and worked with Wipro Net Technologies, Cat Net ISP Tanzania, Cybage and other IT companies.. He currently worksas a technical writer.

Aadya. S. A, known by her pen name Aadya Sain, is a postgraduate student at the Institute of English, Kerala University. She graduated from Govt. College for Women, Thiruvananthapuram. A strong interest in the South Asian languages and their culture led her to learn Japanese; now she has ventured into learning other anguages such as Korean, Chinese and German. He has published some of her Haiku poems in Japanese and its Malayalam and English translation in Upadhwani magazine in 2022. Currently she is working on the translation of contemporary Japanese poems to Malayalam. To become a a successful translator in multiple languages is her goal..

A well narrated story with a deep Message and translated commendably without losing the essence of the original work.

Loved this work.In this busy world where people walk with problems, disappointments, one should open his eyes wide enough to see his fellow beings,who will always stand by you with out expectations. Really loved the translation by Aadya. It was simple and easy to understand. This line “There’s no point in doing anything, so let’s try everything” gives hope.