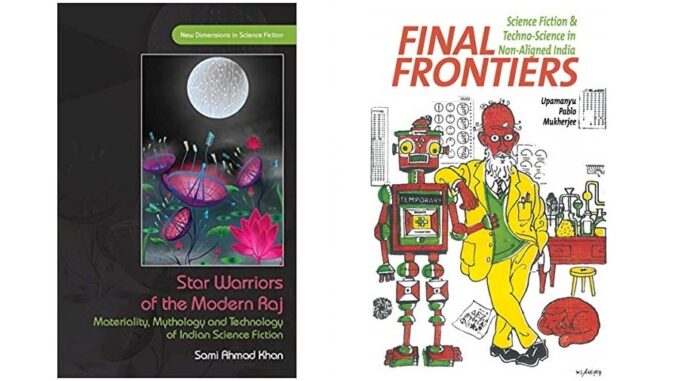

Star Warriors of the Modern Raj: Materiality, Mythology and Technology of Indian Science Fiction. Sami Ahmad Khan. University of Wales Press, 2021. 247 pages

Final Frontiers: Science Fiction & Techno-Science in Non-Aligned India. Upamanyu Pablo Mukherjee. Liverpool University Press, 2020.192 pages.

Barnita Bagchi

I

t is refreshing that we have the recent publication of a number of works on science fiction from India. Two of these recent works are under discussion in this review. The books offer indispensable discussions of science fiction and the relationships of such fiction (a kind of speculative fiction) with utopia, dystopia, fantasy, mythology, and ideology. Cognitive estrangement, as Darko Suvin argued, is fundamental to science fiction, with the reader encountering a strange world that nonetheless has many similarities to that of the reader, triggering disorientation or estrangement. The reader is thereby stimulated to reflect on the fundamental assumptions of society. Khan offers a delightful register of a fan’s guide to Indian science fiction, eschewing Eurocentrism, and avoiding essentialist understandings of SF. Materiality, mythology, ideology, and technology are discussed, with the term TransMIT succinctly capturing the approach. Suvin’s notion of the scifi imagined world as the novel ‘novum’ plays right through the work. Interestingly, Khan prefers the term ‘materiality’ instead of ideology, to capture metaphorically the fusion of mythology, ideology and technology in Indian SF. Mukherjee offers a work which is more formal in academic style, one which deservedly won the 2021 Science Fiction Research Association Book Award for the best first scholarly monograph in SF.

There will be many readers of this review who are familiar with the Ghanada stories of Premendra Mitra, and with the Shonku tales by Ray. A book like Mukherjee’s needed to be written, showing how these tales display convergences and dissonances with the techno-scientific paradigms of Nehruvian India. The book also argues that Indian mid-20th-century science fiction is semi-peripheral in nature, similar to other Third World and even some European SF. The networks of book and press trade in Calcutta or Pune (J.V. Narlikar in mind here) and genteel bourgeoisie affiliations contributed social and cultural capital to writers who were also partly marginal to centres of power in India and abroad. Final Frontiers does a very good job of showing the internationalism of figures like Ray and Mitra, their openness to the world of literature and films from across the world as they knew it. Equally, this book certainly kept this reader refreshingly mindful that speculative and realist fiction are in a sliding scale. It is very good to have quotations from the creator of Ghanada destabilizing easy stereotypical assumptions: Mitra writes that a writer such as he learnt the lessons of life from Hamsun or Gorky. Final Frontiers is great at showing how comic-heroic scientist figures are deployed to raise many questions round authority. Weapons, space, beings from other worlds are skilfully analysed, and related to questions round the development of the world. And the book can show the continuities, not just the differences, between the older SF writers like Narlikar and a contemporary writer and scientist, Vandana Singh.

Mukherjee has a chapter on energy humanities which is one of the most thought-provoking ones in the collection. He applies to the fiction he analyses three fundamental principles of modern energy humanities—an expanded sense of modernity and energy, a recognition of the conceptual and representational challenges posed by modern energy relations, and the capacity of literary-cultural criticism and the works it analyses to face those challenges. This also produces arresting readings of texts such as Satyajit Ray’s Professor Shonku stories; among them, ‘Byomjatrir Diary’ or Space Traveller’s Diary is analysed as presenting its textual seriality as energy that does not dissipate itself. Ray’s Shonku stories probe the boundaries between modern science and other knowledge systems, and often critique the speciesist and gender bias of developmentalism a la Nehru, Mukherjee argues. Ray’s Shonku story titled after the cave of Cochabamba sees the arousal from slumber of an artist of cave-paintings who is also adept at mathematics and technological innovation; the cave is at the border of pre-history and history, and purely linear and reductive views of biological and historical development are utterly disrupted by such stories.

Khan’s book is very attentive to how mythology, technology, ideology, and materiality come together to form 21st century Indian SF. Utilizing metaphors deliberately, it talks about the soul or atman of Indian SF. While being very attentive to the politics of Otherization sometimes found in Indian SF, on the whole, the book concludes that this contemporary mode offers a plurality of voices, and on the whole writes back to parochial and fundamentalist visions. Rich in a plethora of casus-based analysis too, the book is salutary also for making us again aware of the oeuvre of women writers such as Sukanya Datta, zoologist and popularizer of science, or Rimi B. Chatterjee, author of the excellent Signal Red among other books. While I am finishing off this review, I am also answering questions from a woman journalist for a web-based journal, on South Asian speculative fiction by women: paradoxically, a question about which contemporary writers I would particularly recommend makes me think of the need to bridge, even more than we are doing now, the past and present of Indian SF by reading and analysing more, but also by translating more, 20th century bhasha women writers of speculative fiction like Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain and Leela Majumder: figures who were zany, curious, and scientifically minded while being fabulating, and with that quizzical, often biting, perspective towards patriarchy. Works like Mukherjee’s and Khan’s are superb pathways for readers and scholars worldwide to understand how wonderful it will be when we acknowledge the value of Majumder’s environmentally minded SF in Bengali, strewed in numerous works like Batash Bari (House of Wind); happily, academics like myself, Suparno Banerjee, and Debjani Sengupta have been publishing on speculative aspects of Majumder’s works. We need more translations of such work.

Books such as Khan’s and Mukherjee’s offer avenues into understanding the love of speculative fabulation and interest in science of many of these writers: equally, it remains important to remind ourselves, in times of damaging right-wing fundamentalism in India, that Satyajit Ray, for example, excelled at devastating critiques of patriarchal and class-biased religious superstition in films such as Devi (1960), in which a young woman is driven to madness by being made to believe she is a goddess incarnate, or the ironically titled Mahapurush (1965) in his paired films Kapurush o Mahapurush, which makes a film version of a brilliant humorous and satirical Bengali short story, ‘Birinchi Baba’, by Rajsekhar Basu, one which offers a devastating debunking of a fake godman. Rajsekhar Basu was a chemist, humourist, translator, and lexicographer, and his life and oeuvre, as much as Satyalijit Ray’s, enable us to see the many places where Indian SF overlaps with other genres and modes. The books under review also make innovative contributions to a more decolonial understanding of Science Fiction.

*******

Barnita Bagchi is a feminist literary critic and cultural historian, and an Associate Professor in Comparative Literature at Utrecht University in the Netherlands. Her publications include a part-translation with introduction, Sultana’s Dream and Padmarag: Two Feminist Utopias, by Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain (New Delhi: Penguin Classics, 2005), an edited volume, The Politics of the (Im)possible: Utopia and Dystopia Reconsidered (New Delhi, London, Thousand Oaks: SAGE, 2012), a guest-edited Open Library of Humanities open access Special Collection on Utopian Art and Literature from Modern India (2019) and the edited volume Urban Utopias: Memory, Rights, and Speculation (Open access, Kolkata: Jadavpur University Press, 2020).

Also Read Dialogues with South Asian SF Writers

Leave a Reply