An Introduction

Frank Stewart is a respected and honoured poet. His early work, for which he won the Whiting Award, is inspired by his vast reading of Thoreau and the ecological imagination and his abiding interest in two crucial questions: How does one define a moral imagination and its concern for the pain of others who are different and what is the responsibility people have toward all sentient and non-sentient beings? I am fascinated by this new volume of poems by Frank, Still-at-Large (Berkeley, California: El León Literary Arts, 2021), because it refuses to let us forget that since the beginning of the 20th century we, in India and elsewhere, have been living in times of relentless and unashamed national, religious or economic violence; that killers have walked our city streets and villages without remorse and with the confidence that there is no law which can prosecute them. Frank does so with the minimum of words surrounded by blank white spaces. This method of printing forces us to pay attention, even it is only for a moment, to the voices of those who have suffered and survived. It also leaves us bewildered when we are confronted with the heartlessness of those who kill remorselessly. Of course, as those of us who are familiar with either Coleridge’s, ‘The Ancient Mariner’, Paul Celan’s, ‘Death Fuge’ or Yevtushenko’s, Babi Yar’ know, poetry or speech of such remembrance brings no relief, clarity or consolation and yet must be uttered. In his note to me Frank says: “I don’t know how we can write about suffering. Perhaps no one does. But I think that we cannot avoid writing about it, even in a way that ultimately fails, as all our efforts must.’ It is this refusal to stay silent, to speak about the atrocious, however briefly, which makes these poems worth reading and commenting upon.

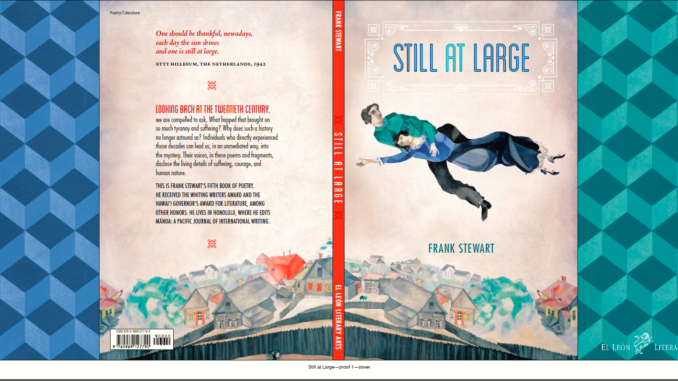

The illustrations are from works by Marc Chagall. Frank Stewart uses some of them in his volume of poems. Alok Bhalla

![]()

Frank Stewart

Still at Large: Poems / Fragments: A Selection

One should be thankful, nowadays,

each day the sun shines

and one is still at large.

Etty Hillesum, The Netherlands, 1942

In order for your own voice to be heard again,

nearer and more vividly,

I link your language to mine from time to time,

inserting in quotes some of the phrases

taken from your writings.

May these portions of your posthumous message,

brought together and presented by me,

serve to open the heart and the mind

of the one who reads them!

Emanuele Artom, Turin, Italy, December 20, 1940

It’s good to know everything.

Shmuel Rotem Czerniaków, Poland, 1930s

![]()

Author’s Note

In his notebooks in 1941, Camus wrote, “Everything is decided. It is simple and straightforward. But then human suffering intervenes and alters all our plans.” The majority of poems and fragments here are moments when plans and suffering meet in the lives of inconsequential men and women—that is, ordinary people whose lives are like everyone else’s. All lives and experiences are significant and consequential to the person who experiences them, of course; they become meaningful to us when we see how tightly significance and insignificance co-exist.

A few of the pieces here are nearly verbatim from the sources where I found them; those sources are noted at the back. Almost all have been shaped and sharpened by me, but none of them are wholly mine.

They are arranged, with few exceptions, chronologically, as their historical context may be helpful to understand the feelings and experiences expressed in them. However, the pages here could be scrambled and have the same coherence; reading them randomly, which I suggest, accomplishes the same effect. History is no more or less than a collection of such moments like these, given coherence when fleeting, insignificant lives are held up to the light. The light is at the bottom of the sea of moments we swim in, and all that’s required to make that light shine is a few words in a solitary, recognizably human voice.

Prologue

For Now

What is that which we hang onto

And which is snuffed out in a second?

I have not yet found a poem that

Encompasses what is happening here—

Much must remain forever unsaid,

Saved up for the hour when

it is handed down to people,

without mediation.

The Russian front, May-June, 1940

I Tell You

The Turks conscripted my father

And this saved us from being rounded up.

You see, the governor in Homs

Sent the village prefect an order

To “poison all the dogs,” which meant

Us Amenians. But the prefect,

Djemal Pasha, knew us.

He ordered the police

To kill all the stray dogs in the streets.

So we were saved. Then he ordered

All the Armenians to change their names.

Homs, Ottoman Empire, 1914

Mother

That night there was nowhere to sleep

Mother slept on the ground

My sister, Khatoun, and me

Sitting near mother

Braiding her hair. A woman passing

Looked at us said

“Why, the poor darlings,

They don’t know their mother has died.”

We were children, how could we know that?

Homs, Ottoman Empire, 1914

Wake Up

You don’t seem to understand what we want.

We want an Armenia without Armenians.

Ankara, Ottoman Empire, December, 1915

The Feast of Vardavar

After the Turks lit the church

Packed with villagers

Intoxicated and merry soldiers danced

Swinging their sabers, beating their chests

They sang

yürü yavrum, yürü!

Dance, children, dance!

I wish my eyes had become blind

So that I would not see.

We escaped but I swear

To me they looked like wild beasts.

Ottoman Empire, 1915

At the Train Station

At the train station, we saw them pleading,

“No! Wait! We will become Muslims! We

will become Germans! We will become

anything you want!” Then the train took them

to Kemah Pass where they cut their throats.

Outside Erzincan, Ottoman Empire, 1915

An Open Field

Farther from the town we reached

An open field. We saw all

The animals had been gathered there,

Our sheep, cows, horses, and so on.

My aunt jumped over the fence

And went over to our cows, hugging them.

But there were soldiers on both sides of

The road to make sure no one swerved

And everyone kept up.

Ottoman Empire, 1915

They Went to the City Hall

And a judge told him, “Child,

Your religion is very bad

And must be renounced. Do you

Renounce it?” He said, evet, effendi,

Yes, sir. “Do you accept the real religion,

The Muslim religion?” Evet, effendi.

The judge said, “Son, your name henceforth

Will be Abdul Rahman oghlu Assad.

Then they gave the boy a fez

And a turban so everyone would know

He was Muslim. Then he had to be

Circumcised, so a religious leader did that.

Afterwards, he could safely go out

On the street. But even then

The Turkish boys would taunt him,

Calling him dönme, turncoat.

Ottoman Empire, 1915

The Book

I had a leather water bottle

Containing about a cup full of water

The children near me were crying

Choor! Choor! Water! Water!

Without being seen

I held out the bottle quickly

Here and there to wet the children’s

lips with a few drops.

I think those drops

Were very precious, and that they were

Recorded in the book of heaven.

Between Marash and Dier el-Zor, Ottoman Empire, June 1915

Turkish Harem

They wore long, blue, sleeveless caftans

And scarves over their shoulders

To shield their faces against the desert winds

Some covered their heads with turbans;

Some had cushions on their heads

Which protected them as they carried heavy loads;

Some had babies in cloth bags on their backs;

Some displayed rings in their nostrils

And had garish, dark-blue tattoos

On their faces bosoms, hands, arms, ankles,

And even their kneecaps.

These women were the lucky ones.

Ras al-Ayn desert, Ottoman Empire, 1915

Beauty, the Oldest Sorrow.

By blackening their faces with dirt or soot

Many girls tried to make themselves ugly

Mama would caution me everyday

“Vergeen, don’t forget to rub dirt on your face.”

She was afraid a soldier would take notice

Of me. I was thirteen.

Ras al-Ayn desert, Ottoman Empire, 1915

Deportees

In the depths of the cedar forest

They came upon tents of black goatskins,

The shelters of Turkish charcoal makers.

“We would have been so happy,”

The priest wrote, “to stop here in that solitude,

To live simply and free

From the unbearable eyes of the police-soldiers.

“We envied those poor workers

But also the startled rabbits that

Jumped from beneath bushes and

Dashed away. And we envied birds

Free in the sky to fly wherever they wished.

“But we were going to the desert

To become handfuls of dust.”

Taurus Mountains, Ottoman Empire, 1916

The Afterlife

During the deportation

I spoke to the captain. “Bey,” I said,

“As a priest, I frighten my congregation

When I tell them their sins

Will make them suffer in the next world

If they won’t atone.

How will you atone for yours?”

“I already atone for mine,” he said.

“After each massacre

I spread my prayer rug and say my namaz,

Thanking Allah

For making me worthy for this jihad.

“My friends wanted me to retire

On account of my old age.

It’s a good thing I didn’t.”

Leaving Yozgat, Ottoman Empire, 1916

![]()

Friendship

After the French soldiers withdrew from Marash

We who had hidden were weak with hunger.

The town was full of Turks firing their weapons

Only Peter, my American friend living there,

Would go with me to the Turkish grain shop

to barter for food. A Turk suddenly ran toward us

And embraced him. “My friend!” he exclaimed,

“How fortunate you did not come to me

For protection! I would have had to kill you.”

Marash, Turkey, 16 February 1920

Beautiful

The way they acted was so proper, so magnificent, so disciplined; they command nothing but respect. The locals could learn a lot from them. Just look at them marching by, on foot or on horseback or with their guns, looking so beautiful, so healthy, and with such cheerful faces; they’re big and sturdy and very neat, making you think, inadvertently, such a pitiful army we have! The people here are so rude and impolite, while they are so proper and polite! It’s easy to see the difference. How dare we fight such a powerful, strong people? No wonder we had to give up fighting after four days, the difference was too great.

The NetherlandsThe Hague, The Netherlands, 1940

His Eyes

A policeman came to their apartment

And wanted to take some of their things.

The woman cried saying

she was a widow with a child.

He said he would take nothing

If she could guess correctly which of his

eyes was the artificial one.

When she guessed the left

He asked her how she knew. Because,

she said, that one has a human look.

Warsaw, Poland, 8 November 1940

Father

I was the girl who played soccer with the boys.

I was the girl who rode a bicycle on the street

Which a lot of Jewish girls didn’t do that.

See, I was born a fighter. I am free. I was always free.

When I was a child my father used to say

That I am dangerous.

Lokov, Poland, 1940

Bridge of Ravens

The new women were holding onto the small bundles

They’d been allowed to take with them—

Curtains, a pot of lard, black bread, a coat.

They saw us as striped silhouettes without faces.

They didn’t know why this was happening to them

Or why they were here. They knew nothing.

At least we knew why we were here.

Ravensbrück, Germany, 1942

Obviously

Obviously it is

Inconvenient

To shoot everybody,

He explained.

Kiev, USSR, April, 1942

Sooner or Later

The wind squealed under the floor

The train had stopped

You could see a skinny horse beside a wire fence.

This time no one got off

to look for the missing children.

Central Europe, 1943

A Journey

From the train we moved five in a row

I was weak and someone put out a hand

I thought it was to help me, but

It was to hit me.

“Russian pigs! Russian bandits!”

Nobody could understand

Why they were being beaten.

We hadn’t learned yet

That this was just the way they behaved.

Ravensbrück, Germany, 1943

A Thin Ray of Brightness

Before dawn, it was hard to see the roads.

We had to concentrate to avoid driving

into the ditches.

At the top of a hill

we could see the outlines of Luxembourg.

The road extended through a forest into the plain.

Ahead the taillights of another column

were disappearing into the woods.

The most beautiful thing I had ever seen.

Outside Luxembourg, Belgium, 1944

More Light

Outside we saw ragged women pillaging,

Their shoulder blades thin as knives.

Some fell into the river,

Others twisted their skirts up to defecate.

We didn’t see no infants except

A red-haired girl with inflamed skin

Who looked like she was sleeping.

Villagers brought us hot broth and horsemeat.

Later, three of us got down from the train

To see if anyone was around,

The only light we had was some stolen candles,

Which wasn’t enough.

Central Europe, 1944

Abandoned

The sweet May rain

Runs down my cheeks.

In a rice paddy an artillery shell

Wallows in the mud.

Southern Okinawa, 1945

The Finest Thing

You must be attached body and soul

And with all the forces of your heart

And character to him.

You must regard yourself as his children

Whom nothing on earth

Could ever make waver

In their unconditional loyalty.

This is the greatest and finest thing

In a man’s life—unconditional

Loyal devotion to the great man

Who is his leader.

Radio broadcast, Berlin, Germany, 20 February 1945

Defiance

He was defiant at his trial.

When the judge asked him

How he’d been able to betray

His fellow partisans, he replied

“I think for a million bucks

you would have done the same thing.”

Prague, Czechoslovakia, 1945

Pancakes

They began wandering in circles

Because of the darkness and heavy snow.

Luminescent rockets streaked through the heavens.

One of them said he swore he could see

His mother carrying warm pancakes for

Everyone. Those who did not die of the cold

Were captured by the Chetniks because

Their feet were frozen, or because

A child would begin crying.

Birać Mountains, 1992

Foreigners

The children asked their teacher,

Who was from Algeria, why after

All her years living in Paris

She walked down the street zigzag.

“This is how you avoid a bullet,”

She answered. How strange they all

Had thought, until much later

When they returned to Croatia

And the bombing began.

Zagreb, Croatia, 1992

Dear Diary

I ran across the bridge today

To see Grandma and Granddad.

They cried with joy. They’ve lost weight

And aged since I last saw them

Four months ago. They told me

I had grown, that I was now a big girl,

Though I am only eleven. That’s nature

At work. Children grow, and

Elderly age. That’s how it is

With those of us who are still alive.

Sarajevo, September 1992

Precisely

Offended by the Dutch peacekeeper

who called him a Nazi, the Serb captain

said, “I understand his family’s story,

OK, but I don’t understand why

he’s making such a fuss,”

referring to the deportations.

“I understand why he gets emotional,

but they’re not Jews, they’re Muslims.”

Near Bratunac, Bosnia, July 1995

![]()

On the Bus

On the buses as they drove past

I could see the women.

Pressing their faces to the windows,

eyes wide, they saw the men

lying in the grass by the road,

pools of blood under

their slashed necks. The women

forced themselves to look

in order to see if any of the men

were their husbands, fathers, and sons.

Outside Srebrenica1995

I Told Them

“Look at me! You haven’t killed all of us!”

Srebrenica, 1999

Music

The medic jabbed him with something

Then we both looked over the trench.

It was a seventeen-year-old girl soldier

Named Jacky, blonde ponytail, small Koran

On a leather strap around her neck. Some said

She was the commandant’s mistress,

But in her small tough voice she said

She was there to fight. Running with a box

Of ammunition beside a friend with short,

Spiked hair, holding a Walkman playing hip-hop.

They left the music on during the shelling.

Near Kosare, Kosovo, 12 May 1999

Look, Look

He stood near the tent

On sentry duty, his helmet on,

An old Kalashnikov slung on his shoulder,

A cigarette in the corner of his mouth.

He was staring at the sky, bright blue

Flecked with pink and orange.

A perfect Turner landscape.

He was talking to himself, mumbling,

Excited as a child. “Look, look at

The light,” he said. “The beautiful light!”

Then he saw I was awake and

Turned to me with joy. “Look,

At the sky! We’re still alive! Isn’t it

Wonderful! We’re still alive!”

I fell asleep again and when I woke up

Someone said he had gone to the front.

Near Kosare, Kosovo Border, May 1999

For the Record

Much later, when she met with the Dutch

Researcher, he seemed unaware

That children had been killed at Potočari.

“There were no children at Potočari,”

he said. She showed him

the documents that proved there were:

“Then,” she asked, “did I kill my children?

Did I undress them?”

“There were no children,” he repeated.

“No one knows where you women hid them.”

The Hague, The Netherlands, 2004

Be

Ruthless without anger

Aggressive without anger

Meeting violence with greater violence

Void of emotion

Not hindered by potential death

Be the loving father, spouse, and friend

As well as the ruthless killer.

Louisville, Kentucky, 2013

Sugar

I was so afraid I wanted to throw up.

I hugged my doll tight, saying “Don’t be afraid,

don’t be afraid, I’m here with you.”

My parents gave us sugar, saying

it would help us be less afraid…

but I found it didn’t change anything for me!

Aleppo, Syria, 2013

Graffiti

Brother do not worry

the Belgian police have released me

for the 23rd time. Back to the lorry…

**

Remember put the tube in your mouth

and the other end out of the lorry’s tarp cover

so you can breath

**

be careful that dog a lot

put oil on you & the dog cannot scent

**

Just look yourself and come yourself

as soon as possible. I am with Pichiu

there is much of control in the streets and

dangerous. If you have read this take the way

to Italy be careful what you doing

**

BE CAREFUL THEY DO CATCH YOU WITH DOGS IN THE PORT!!!

**

I am Sonu Kumar age 17

Brother don’t worry moreover

I have possess a paper of Greece

**

Tomorrow we will try again — we will also …

**

I am Arash in Zeebrugge I have been sent back again

The one from the UK has deceive me

And also Belgium didn’t mean anything

The human trafficker is Asad

**

Have try 12 times without success

Saw it too late left the assholes behind

Port of Zeebrugge, Belgium, 2014

Decency

He had called his parents in a rush on Aug. 8.

“Mama, Papa I love you! Hi to everyone!

Kiss my daughter for me.” His mother was told

Nine days later by an emissary of the Russian army

That her son Konstantin had died at the Ukranian border

In “army exercises.” When she asked,

“Do you believe the words you are telling me?”

He had the decency to reply that he did not.

Russian–Ukranian border, 13 August 2014

![]()

********

Frank Stewart has been editor of Mānoa: a Pacific Journal of International Writing since 1989. He is an essayist, translator, and the author of four books of poetry. For his poetry, he was awarded the prestigious Whiting Writers’ Award in New York in 1986 and other awards, including the Hawai'i Governor's Award for Literature. He has edited eight anthologies on the contemporary literature and environment of Hawai‘i, Asia, and the Pacific. He represented American writers at the Asia-Pacific Conference on Indigenous and Contemporary Poetry, in Manila; was a U.S. representative to the Taipei International Poetry Festival, in Taiwan; the American representative to the Commonwealth Games/Literature in New Delhi.

Leave a Reply