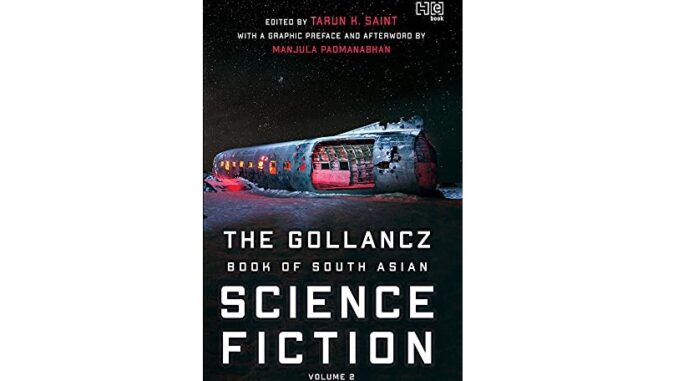

The Gollancz Book of South Asian Science Fiction Volume 2. Tarun K. Saint (Editor). Preface by Manjula Padmanabhan. Hatchette India. 8 October 2021. 488 pages

Shweta Khilnani

(Of Home, History, Humans and Beyond!)

T

he second edition of the Gollancz Book of South Asian Fiction, edited by Tarun K. Saint, with a graphic preface by Manjula Padmanabhan, builds on the ideals established by the first collection, which appeared in early 2019. The collection of fiction and poetry was a unique effort as it provided a platform for writers and readers to unravel the textures and feelings of South Asian science fiction and fantasy. The second edition expands its horizons in multiple ways – it features a more diverse group of writers from Indian, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Tibet and the stories challenge established generic boundaries, producing a rich blend of SF, horror and fantasy. The hybrid, genre-bending stories add a new dimension to the existing corpus of South Asian literature and seek to represent the contemporary moment with all its myriad nuances. The short stories and poems, with their fantastical and surreal worlds, negotiate a distinctly South Asian past and simultaneously attempt to transcend it. On the one hand, they are manifestations of the search for appropriate metaphors to succinctly communicate the historical and contemporary lived experiences of people from South Asia (itself a rather broad category), while on the other hand, they sometimes reveal a desire to overcome the ghosts of the colonial past, or at least, reconceptualise them in different terms.

The collection begins with Shiv Ramdas’ “And Now His Lordship is Laughing”, nominated for the 2019 Nebula and Hugo Awards. The story is set in colonial Bengal in 1943 and follows Apa, an old woman acclaimed for her putul making skills. She adamantly refuses to make one of her “dolls” at the behest of the Governor of Bengal in the midst of a brutal famine which kills her grandson, Nilesh. The famine is a result of the Denial of Rice policy, designed to provide resources to the Allied troops. This historical fantasy employs the voodoo doll with its native magic spell as Apa’s subversive tool for revenge.

Tellingly, the resistance comes not in the form of weapons or armed revolt; instead, it is realised through laughter as cries of the “high, shrill crackle” of the putul reverberate ceaselessly through the halls of the English masters.

The colonial subject’s rebellion is uniquely conceptualised by Ramdas as the surplus of mirth and laughter counterposed against the deprivation caused by the famine.

This historical fantasy then gives way to a rich array of fantastical worlds, right from the surreal land that is dreamed in Tashan Mehta’s “The Traveller” to the grotesque in Muhammed Zafar Iqbal’s “The Zoo” to the Kafkaesque in “The Ministry of Relevance” by Arjun Raj Gaind. While some of them are set in the near or distant future, others exist in an atemporal setting. Of course, SF shares a knotty relation with time. While it is usually assumed to be a future-oriented genre, owing to its ability to render imaginative visions of the future, it is equally concerned with the past and the present. Fredric Jameson has written extensively about SF and temporality wherein he argues that SF illustrates the present moment, often tangentially, and attempts to break through the impasse created by the conditions of a late capitalist and consumerist society which obfuscate our engagement with the present in any meaningful manner. Through its representation of an imagined future, the present becomes the historical past, and this temporal disjunction facilitates a critical engagement with contemporary reality. This has been a traditional trope which can be found in the most iconic SF narratives including Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. Both these novels, like countless other examples of SF, present a dystopic future ripe with totalitarianism and surveillance. With respect to this vision of the future, the present moment becomes the past and we are able to apprehend it as a historical reality.

Several stories from the collection employ this peculiar feature of SF to draw attention to contemporary alarming political and cultural developments in parts of South Asia. In Jayaprakash Satyamurthy’s “Dimensions of Life Under Fascism”, in the “twenty-sixth year of the MoSha Rajya” in “Bharat” (not India), people mysteriously turn into two-dimensional flat cardboard cut-outs versions of themselves while consuming “some form of state mandated spiritual content”.

Flatness becomes a metaphor for rigid cultural homogeneity which discourages any resistance or deviation from the state sanctioned way of life.

While the dystopia imagined in this story is a result of the lack of depth or diversity of any kind, in Soham Guha’s “The Song of Ice” (translated by Arunava Sinha), the dystopic conditions emerge from a more material, physical factor – the extreme paucity of food to sustain the inhabitants of the huge sprawling city of Calcutta – all 320 of them. An ecological catastrophe of unmatched proportions results in an acute shortage of food supplies, which in turn, leads to the division of the city into camps based on religious, communal identities. The dystopic future becomes a reflection of the painful history of communal relations marred by hostility and violence. Such is the longevity of the spectre of Indian nationalism and its discontents that they reverberate even in the aftermath of an ecological catastrophe that threatens to make humans extinct globally. At the same time, the prospect of the extinction of the species itself and the encounter with the sheer abjectness of cannibalism, engenders a reconsideration of communal hostilities. Historical conflicts seem to pale in comparison to the struggle for survival of a species and the desire to transcend one’s history is articulated. This coming together of historical identity with the notion of existence as a species makes for a fascinating paradigm, one that is treated in depth with more nuance in other stories from the collection, penned by Vandana Singh and Giti Chandra .

The figure of the ‘other’ manifests itself in a variety of ways in SF in general, and this collection of stories in particular. In addition to the obvious figure of the alien, a being from another celestial body or universe, one also finds members of non-human origins, whether in the form of The Celestial One in Chandra’s “A Species of Least Concern” or the genial djinn in Saad Z. Hossain’s “Bring your Own Spoon”. However, there is another manifestation of the ‘other’ which is a pervasive presence in the collection, that of the immigrant, the outsider, the person in exile. Kalsang Yangzom’s “The Crossing” and Salik Shah’s “Shambhala”, both based in Tibet, articulate the precarious lives and experiences of refugees or immigrants, ready to risk their present in the search for a more hopeful future. Senna Ahmad’s “The Glow-in-the-Dark Girls” comments poignantly on the dispensability of the lives of refugees steeped in poverty. The girls from the title of the story are capable of setting places on fire owing to some genetic experiments carried out on them presumably by the military. Even as their ability to cause destruction maims their own bodies, their suffering pales in comparison to the plight of a dead American teenager backpacking around the world. The introduction of the novum, characteristic to SF as a genre, often understood as the one radical departure from reality that gives a narrative a distinct science-fictional feel, allows these stories to bring out the precarity of the lives and experiences of refugees and immigrants. At the same time, Sami Ahmad Khan’s “Biryani Bagh”, a play on Shaheen Bagh, which became the epicentre of the protests against CAA laws in 2020, demonstrates the many phenomena through which the ‘other’ as a source of threat is manufactured by people in positions of political power. The techno-dystopic, cyberpunk world is marked by the presence of intensive data surveillance machines and forms of genetic purification, along with a society marked by hostile communal relations.

Once again, the history of the nation haunts its future(s) as the ‘othering’ of minority religious groups reaches its frightening climax.

Even as a number of stories present an alarming vision of the future marked by precarity of resources, excessive surveillance and a debilitating dependence on technology, it also offers fleeting moments of hope, resilience and survival. In “Bring Your Own Spoon” by Saad Z. Hossain, set in an ecologically ravished Dhaka, the brief sense of respite comes in the form of an unlikely alliance between a human being and a djinn, who come together to open a restaurant. Defying all odds, their humble food joint becomes a community kitchen of sorts, where the smell and taste of long-forgotten dishes like grilled fish and rice stimulates conversations between people who exist at the very margins of the society. The issue of survival assumes a more central role in Giti Chandra’s “A Species of Least Concern” as the sole female survivor from the planet goes in search of a new home and a new progeny. The title is a reference to a category of species which could survive and preserve regardless of a complete lack of attention or care. Such species of ‘least concern’ can withstand physical illness, victimisation, hostility, predatory behaviour, while often overlooked, are perhaps best suited for survival.

In this gendered take on the issue of survival and generational responsibility, Chandra cleverly draws attention towards a characteristically masculine (read violent) way of approaching humanity’s relationship with Earth, often imagined as a feminised, motherly entity.

The story makes us wonder if we treat our planet just like we treat women, as a species of least concern – inflicting all sorts of damage upon it but still expecting it to survive?

And if this masculine treatment, premised on the denial of the feminine, has only led to monumental disaster, perhaps it is time to reconceptualise this gendered relationship.

Also read Dialogues With South Asian SF Writers

In a similar vein, Vandana Singh’s brilliant story “A Different Sea” engenders a broader reconceptualization of our very existence as human beings. Through her encounters with different beings, the protagonist, Rasika inches towards a radically different understanding of herself and her place in the world. The story follows her as she attempts to build bridges across time and space with the historical, generational and species ‘other’.

In her professional endeavour, she is preoccupied with Khanaa, a historical figure separated from her by a couple of centuries, just like her private life is an attempt to solve the mystery that is her daughter and care for Khatru, a genial, lovable alien who arrived at her doorstep during a thunderstorm. Through her encounter with this form of radical alterity, a form of extra-terrestrial life, Rasika inherits a new form of relationality with the world around her. It is quite literally, a different kind of ‘worlding’ for her, a form of existence where one embraces the other, without silencing them or appropriating their position. This is accompanied by an acknowledgement of the intimacy of the relationships that constitute the world. This form of ‘worlding’ premised on care, ethics and engagement, is instantly reminiscent of the notion of ‘planetarity’, discussed extensively by Gayatri Spivak in The Death of a Discipline where Spivak proposes to replace the notion of the globe with that of the planet (2003).

More specifically, it entails a shift from the “globe as financial-technocratic system towards planet as world-ecology” (Elias and Moraru 2015). Globalisation has always been steeped in the vocabulary of technology, acceleration and homogeneity. On the other hand, the notion of planetarity is premised on the model of relationality and a return to ethics. It promotes genuine contact and deep familiarisation with radical alterity in terms of their languages, habits, belief structures etc. In doing so, it also moves towards a different notion of collectivity and identity formation.

Instead of establishing communities on the notion of imagined similarities and differences, a planetary approach would encourage us to understand the differences, to inhabit the space of the other and to accept that we are just one among many organisms that inhabit the planet.

It goes without saying that this is a radical departure from traditional forms of community formation, especially the rhetoric of colonial and postcolonial ideology which concerns itself deeply with the category of the ‘other’. It is undoubtedly a compelling idea which presents the possibility of a world where we might be able to transcend the spectre of the past and mould a different future.

One wonders if we, a people with a shared history, can build this bridge from self to self, as Rasika does in Vandana Singh’s story, or, are we destined to live with the past in perpetuity, quite like Melli from Giti Chandra’s story who has inherited memories “coded into her DNA by centuries of trauma”.

***

References: Jameson, Fredric. “Progress v/s Utopia:, Or, Can We Imagine The Future?”. Science Fiction Studies, vol. 9, no. 2, 1982, pp. 147-158. Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. The Death of a Discipline. New York: Columbia University Press, 2003. Elias, Amy J. and Moraru Christian. “Introduction. The Planetary Condition.” The Planetary Turn: Relationality and Geo-Aesthetics in the Twenty First Century. Eds. Amy J Elias And Christian Moraru. Illinios: Northwestern University Press 2015.

*******

Shweta Khilnani is a PhD scholar at the Department of English, University of Delhi. She also teaches English Literature at SGTB Khalsa College, University of Delhi. Her PhD dissertation focuses on the nexus between the literary, the affective and the political with respect to digital narratives. Among her publications are an co-edited anthology titled Imagining Worlds, Mapping Possibilities: Select Science Fiction Stories (2020) and a forthcoming co-edited anthology titled Science Fiction in India: Parallel Worlds and Postcolonial Paradigms.

Shweta Khilnani in The Beacon

Leave a Reply