https://www.theheritagelab.in/india-partition-art/

Alok Bhalla

1

A

strange and dangerous paradox that seems to lie at the very heart of western modernity. On the one hand, modernity’s morally exhilarating philosophic and social urge has been to define itself as secular, rational and cosmopolitan. Modernity’s liberal philosophers, whatever their subtler differences, have declared boldly, and often, that what motivates human beings to act, what gives them their ethical and aesthetic capacities for judgment, what enables them to live in flourishing communities is that each of them needs the other. Without the gaze of the other, without the mirror of the eyes of the other in which they see honour or contempt, beauty or desire, invitation to sociability or unsympathetic dismissal, human beings would not be able to acquire an identity. Tzvetan Todorov asserts that because human beings need the recognition and empathetic attention of others that they acquire that “inner incarnation which we call conscience.”

And at the same time, much of modern politics, both in the west and elsewhere, has been played out in contempt of the other. By asserting a unique national, racial, linguistic or religious identity, the modern West has violently and arrogantly swept away every other mode of thinking, living and worshipping and so supported forms of evil. Most communities now have an imagined past in which both divine grace as well as humiliation at the hands of imaginary Others are so mingled as to demand vengeance for historical wrongs.

Every new-fashioned and resentful assertion of a human fragment, an ethnic enclave, a religious sect, a racial category or a linguistic exclusivity has not only been accompanied by the spectacle of mindless slogans, intolerant sermons, political invective or crass greed, but has also required enforcement by brutal censorship, mythic histories, armed thuggery and finally genocide.

The struggle to form and secure homogenous national, religious or ethnic entities has more often than not resulted in the creation of countless borders of sorrow; and within those “border areas of the mind,” people who do not belong to particular pathologies of fixed identities lose not only their families and their homes but are also prevented from discovering who they are. It is possible to argue that the violent formations of armed national conclaves in the past century are a fulfillment of the old and sad Hobbesian assumption that human life, short as it is, can only be conducted in a state of permanent, bloody and implacable conflict, with every group against every other group.

Unfortunately, Hobbes continues to be the representative philosopher of modernity’s expression of an insularity in which in which every group is hostile to every other, and he seems to have articulated the basis for the hysterical style of passionate resentment we see in the ways various identities defend themselves these days – or, perhaps, always have. Thus, the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben, searching anew for the hidden, “inner demon” of a Europe which still cannot imagine sovereignty without violence, finds the first use of the word holocaust, in relation to the massacre of Jews in England, in a medieval chronicle recording the installation of King Richard I in 1189. According to the chronicler, Richard of Duize, the inhabitants of London celebrated the coronation with a fiery pogrom:

“The very day of the coronation of the king, at about the hour in which the Son was burnt for the Father, they began in London to burn the Jews for their father the demon…; and their celebration of this mystery lasted so long that the holocaust could not be completed before the next day. And the other cities and towns of the region imitated the faith of the inhabitants of London and, with the same devotion, sent their bloodsuckers to hell…”

It seems, then, that since Medieval times national, racial and religious modernities have continued to assume that in a cruelly politicized and economically competitive world it is best to negate the moral worth of the other; that the creation of a plurality cultures—created out of a free conversation “face to face” with the Other, and conducted in open, agnostic spaces without fear of coercion — is not only impossible but is also a threat to a community’s material and regional survival.

If, as the poet Octavio Paz says, irony is the breath of the fallen devil, then it is darkly ironic that the latest antagonistic voices in the divorce of the moral from the political, the religious from the socially responsible, and the individual from the rest of mankind belong, are expressed on one hand by the fine Polish journalist, Ryzard Kapuscinski, and on the other by Avigdor Lieberman, the founder of the right wing political party self-righteously named, Israel Beitenu — “Israel is our Home.” Trying to explain the revival of the anti-Semitic, racist and xenophobic ‘Law and Order Party’ recently in Poland, Kapuscinski says:

You know, if we did not have the figure of The Jew, we would invent something else…In the collective imagination of the Poles, The Other coalesced into the idea of The Jew. For a long time, the Communists had supplanted this idea of The Jew. Now that communism has ended, The Jew is back to being the symbol of the Other of collective hatred.

As if to darken this irony further and so add to the gloom of our modern hell, when the Jewish leader, Lieberman, was asked about the nature of the latest round of conflict with the Palestinians he said:

“What is, really, the reason for the longstanding conflict between Jews and Arabs, between Israel and the Palestinians? Every place around the world where you have two religions, two languages, you have friction, you have conflict. I don’t believe in coexistence. We can be neighbors, but cannot stay together.” Echoing one of the best critics of holocaust literature, Lawrence Langer, one can say that even now, after the experience of so many decades of religious and ethnic atrocities, the goal of life still seems to be the death of others.

What is distressing is that even after the experience of so many decades of religious and ethnic atrocities, the goal of life still seems to be the death of Others.

Also read Portraits of Unspeakable Anguish

It is not surprising that at the base of much of contemporary European and American literatures about identities lies the unstated and unacknowledged assumption that there are natural differences and inequalities between races, religions or cultures. One is likely to find there an unquestioned acceptance of the fact that partitions, apartheids or ethnic boundaries are the natural and inevitable result of long histories of violent aversion between different religious groups like the Christians, Jews and Muslims, as well as between a variety of ethnic and racial groups (consider the archetypal antagonisms of the Serbs, Croats, Slavs, Basques Albanians, Turks, Greeks, Armenians, Spaniards, Irish, Scots, and of course the intense contempt each of them have for red, brown, yellow and black human beings).

2

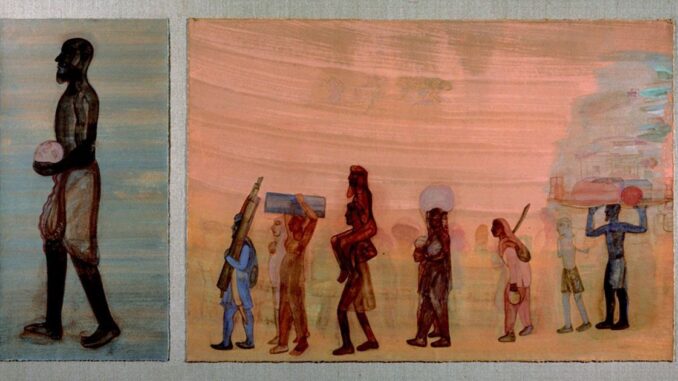

As in Europe or America, where boundaries were carved out to protect linguistic, religious or ethnic homogeneity, the marking of religiously defined political borders between India and Pakistan in 1947 was accompanied by genocidal violence and the largest single migration in history. More than two million people were killed in the name of various gods and about twelve million were driven out of their homes and forced to find shelter in places which had never figured in their emotional or devotional maps. Unlike Europe, Australia or America, however, the voices of protest, even in the midst of atrocities, were not reduced to a whispered undertone. From the first moment when the demands for religious separation and cultural uniqueness were made by some discontented and ambitious Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs, there were a large number of people who protested. They understood that no debates about religious or ethnic identity can be conducted in the public realm without paranoiac hatred of the others colouring the very fabric of daily life.

Instead, they continued to assert, publicly and often in street protests, prayer meetings, newspapers and literary discourses that not only was the present slaughter contrary to the long and intricately textured religious history of India, it was also inimical to the ‘upmaking’ (Ralph Waldo Emerson’s word) of a new, intelligible and rational nation which was possible only if there was space for a rich plurality of ideas, cultures and faiths to continue to engage respectfully with each other.

These were not sentimental voices mixing nostalgia for a world that was merely a fable and desire for a society that could be dismissed as merely idealised. They were, rather, the hopes of a people who were shocked by the sudden and unexpected collapse of an old historical compact which had once been a part of their ordinary lives in the subcontinent; the appeals of Hindus, Muslims, Parsis and Sikhs to restore those normative conditions in which their religious and moral identities had acquired a significance and a value through their daily interactions with each other. Unwilling to bestow legitimacy to the proponents of the ‘the two-nation theory’ of the Muslim League and the calls for separation by fundamentalist Hindus and Sikhs, they refused to abandon their deeply engrained conviction based on lived experiences that different religions had founded their rightful habitation in the Indian subcontinent.

Their repeated calls to sanity are perhaps best exemplified by Gandhi’s admonitions to warring religious factions, with each group asserting its own righteousness and laying claims to greater suffering. “It is a sin,” he declared, “to feel proud of one’s community or caste. It is ignorance too.” Caught as they were, he told them, in a crisis caused by their own obtuseness and momentary amnesia caused either by fear or ambition they should cease lamenting for themselves and turn in sympathy to others who had suffered as much. If they could do that they would understand that human beings, irrespective of the religious identities, comprehend pain in the same way. As a moral consequence of such an understanding, they would instinctively desist from participating in the wretched cycle of wrong for wrong and try harder to save their neighbours from being wounded and their homes from being ruined. Their only dharma, he maintained, was to protect and nurture life wherever it flourished.

It was a pernicious superstition, he said, to claim that there was or ever could be, historically or in the future, a Hindu, Muslim or Sikh India, or that their prayers in temples, mosques or gurudwaras were a measure of their godliness. If they stopped behaving like mobs, armed with daggers, religious invectives and vulgar nationalist zeal, they would realize that god was not more remarkable than a man who abides by the good and home a place where one could live by the covenants of friendship with one’s neighbours. They would, then, realize the only truth that mattered — that “God is life” and that the preservation of life was a sufficient prayer.

3

Partition novels invariably begin by locating themselves within the syncretic cultural and religious habitat Gandhi and others spoke about, and then record in shocked surprise its sudden and brutal destruction. They commemorate a historically available civilisational ethic, which involves both gracefulness towards the self and civility towards others and, at the same time, record how a heterogeneous culture is ruined by the politics of exclusionary identities and the stigmatization of others. It is this doubleness of vision which ensures that partition novels are neither hopelessly utopian nor despairingly vengeful narratives, neither naïve parables about a world that never was nor dossiers of terror. None of the fictional texts claim that historically the relations between different religious groups were always free from suspicion or stupid abuse. Indeed, most of them readily acknowledge that, as in any civil society, there were occasions when religious differences led to murder and arson. But they also record that over a long duration of time such moments were always rare and transient.

That is perhaps why nearly all partition narratives, whether they speak redemptively or despairingly about the future of the countries that came into being in 1947, have three structural and thematic elements in common. The first is that there are hardly any communally charged and vengeful stories which claim holiness for one religious community while laying the charge of endless hooliganism on the other. Rarely do the writers of partition fiction speak about abstract religious entities called Hindus and Muslims, Parsis and Sikhs whose economic and social rights needed to be legally and politically defined, and whose “religiously-informed identities” needed, like some endangered species, special enclaves of protection from other religious predators. Instead, partition novels give a human shape and a human voice to those in whose name, and for whose benefit, the sordid politics of the religious division of the subcontinent was enacted.

The second is that there is almost no fictional text which presents the partition as an inevitable consequence of an ancient hatred between Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs. And since fictional memory refuses to assert that religious communities in pre-partition India felt alienated from each other in their daily lives, there is in the beginning of these texts a note of utter bewilderment at the violence that accompanied the division which quickly turns into rage. They present with great sympathy characters who can neither be consoled nor be urged to forgive. Yet, it is imperative to record that these novels are also instinct with pity and remorse. They truthfully acknowledge the fact that along with many who acted reprehensibly and meanly, there were a countless number of people who were willing to risk offering help to people whose religious identities were different from their own and were shocked when their efforts proved futile.

There are characters in countless novels who say quite suddenly, and without being able to give any reason for it, to the other standing before them at the very brink of extinction, “I want you to be” (St Augustine’s phrase).

They understood that they had never in the past chosen their neighbours, and that in a good society they never should have the right to do so. Hannah Arendt, in her great study of the politics of violence, says that such Augustinian affirmation of the right of the other to survive is a “miracle” enough in dark times.

Ironically, the third element that marks partition fiction is that, even as their characters speak nostalgically about the homes left behind, they complain bitterly that the places they have migrated to are strangely godless. Partition novelists invariably begin by noting that a majority of the migrants were ordinary people who were indistinguishable from each other as Hindus, Muslim or Sikhs. The migrants had not chosen to leave their towns and villages. But by 1947 a majority of them had no other option. Most migrants understood that, far from being participants in ‘pilgrim time,’they were merely poor players trapped in nightmares of migration, exile and alienation. They remembered their past nostalgically, and they thought that their present was devoid of moral power and civilisational purpose.

Their civil spaces had lost coherence, their time had become fragmented, and they did not know how to retrieve their lives again and remake their homes. They were left with a few belongings, some slogans about god, martyrdom, identity and revenge, and a wealth of nostalgic memories of a lost culture and a betrayed tradition.

That is why it is intriguing to note that, while the partition may have been over religious differences, there are no instances of piety and religiosity in partition fiction. Partition novelists cannot imagine characters who go to temples or mosques to offer thanks for their deliverance from an iniquitous past lived amidst unbelievers or heretics. The places where the refugees settle have neither sacred spaces nor devotees. Indeed, for the migrants in partition fiction, the religious division of the subcontinent is the end of their life-story not the beginning of new entanglements in human-time or a pilgrimage towards the divine.

4

A few vignettes from three randomly selected partition narratives should illustrate my contention that for partition fiction writers the politics of religious identities was not only paranoiac but also based on fabricated history.

I. Perhaps, the most poignant lament in partition fiction over the loss of the idea of the religious as a result of the partition is in the work of, Saadat Hasan Manto, a man scornful of all declarations of religiosity. In “Dekh Kabira Roya” (Kabir Wept When He Saw), a text made up of a series of shifting scenes, Manto records through the eyes of Kabir, the great saint-poet of Hindu-Muslim amity, the spiritual ruin of Lahore after 1947. The fifteenth century mystic, Kabir, used to sing against all forms of religious bigotry:

“You slaughter living beings and call it religion

Hey brother, what would irreligion be?

Great Saint – that’s how you love to greet each other:

Who then would you call a murderer?”

As the modern, post-partition Kabir of Manto wanders through the city, he weeps not only over the vandalism of the past and the corruption of the present, but also at the signs of a merciless future the exiled migrants shall face in Pakistan and India. The historical poet, Kabir, believed that his songs were ecstatic dialogues with other men and God. In the fictional text, however, the people Kabir meets in Lahore obscure the distinction between words and daggers, and confuse their passion for slogans with thought. Kabir regrets that beauty is no longer an attribute of God and that language no longer honours human beings. The migrants, who have taken over the city desire nothing but wealth and power, while he, the visionary poet, has inherited only a soulless, godless city. Everywhere he goes, he watches, with tears in his eyes, what men say and do to each other.

Read here When Kabir Saw, he Wept…

One day, Kabir sees a street-vendor tearing pages from a book of religious songs by the remarkable Hindu visionary poet, Surdas, to make paper bags. Tears begin to flow down Kabir’s face. When the vendor asks him why he is weeping, he says “Poems by Bhagat [Saint] Surdas are printed on these pages…Don’t insult them by making paper bags out of them.” The vendor replies: “A man who is named ‘Soordas’ can never be a bhagat.” The vendor’s taunt is made up of a foul pun on the words ‘sur’ and ‘soor’. Sur in Sanskrit means melody and harmony as well as angel and god, but when slurred over is the word for ‘pig’ (soor) in Punjabi. People merely laugh at Kabir, while he laments because he knows that an entire generation has lost the cultural and religious archive of the subcontinent.

II. In Joginder Paul’s Urdu novel, Khwabrau (1991) [The Sleepwalkers] Muslims from Lucknow are so grief-stricken by their exodus to Karachi that, brick by brick, lane by lane, ghazal by ghazal, they seek to rebuild the city they had left behind. They know, beyond reason and debate, that their civilisational being, and hence their home, lies in pre-partition Lucknow. And they are so absolutely convinced that their identity as Muslims is crafted out of a generations of non-antagonistic dialogue with the Hindus that they long for a renewal and continuation of that relationship.

Their Lucknow was a place of agnostic, non-sectarian civil spaces where it was possible for Hindus and Muslims to talk to each other about everything from God’s enigmatic ways to the taste of mangoes.

No amount of Muslim League rhetoric about Hindu oppression and Pakistan as the beginning of sacred time can persuade them otherwise.

They refuse to accept the ignominy of their migration, and their sorrow at having been forced out of Lucknow is unforgiving and unyielding. Migrants from other cities accept the reality of their new life in Karachi; they look at its map and make out of its streets, markets or gardens a new cartography of home. The migrants from Lucknow, however, let their memories spread through the map of Karachi and stain it like watermarks. They retreat so far into their dream-life of Lucknow that they seem distracted and incoherent to others who think of their confused longings for ‘home’ as a form of madness.

The irony of the novel is that even decades later, its protagonist is still a mohajir (an outsider) – a Muslim from Lucknow who finds it impossible to establish a sense of community with the Sindhi Muslims who believe that they have a prior and foundational claim over the city. In the abstract, it may have been possible for the two-nation theorists of the Muslim League to argue, as it always is for myth-making nationalists, that Pakistani nationalism was Muslim nationalism and that both derived their legitimacy from the non-territorial community of Islam.

But life is always a little more untidy and far more enigmatic than the dogma-driven ideologues either know or care to understand, and home is a place which cannot be constructed by political or religious geniis.

In the novel the effort to create a new Pakistani civilization collapses when the protagonist’s house is bombed by a militant Sindhi. His wife, elder son and grandson are killed. At that moment, he is shocked into the awareness that for the past fifty years he has been living in Karachi and not in Lucknow. His ‘madness’ now takes an unexpected turn. He decides to pack up his bags and go back ‘home’ – home to Lucknow where he thinks his wife, children and grandchildren are waiting for him. “I have seen your Karachi to my heart’s content. I am homesick now. Send me back to my Lucknow,” he pleads with the survivors. The historian, Mushirul Hassan, is right when he says that the irony of Jinnah’s dream of a Muslim homeland was that “its consequences were far worse than its causes.” The novel derives its pathos from the fact that the partition makes the protagonist a stranger both in Karachi and in Lucknow.He weeps as he prays, not only to Allah, but also to Khwaja Khizr, the patron saint of all Hindu and Muslim travellers, to see all mohajirs (outsiders) safely back to the places where they belong.

III. I met the distinguished Pakistani fiction writer, Intizar Husain in 1992 when I was working on my anthology of partition stories. The first thing he said to me, as we began to talk about the partition, was: “I have no idea what a purely Islamic identity is.” The creation of Pakistan, he said, was now an irreversible fact, but there was nothing “historically inevitable” about its emergence. To assert that religious identities in India were formed in opposition to each other, he said, was not only bad history but also bad metaphysics. The Mahabharata, the Buddhist tales, or the Gita were as much a part of his Muslim inheritance as the Koran and the songs of the Sufi saints.

Trying to give shape to his unique understanding of his Shia Muslim identity in the Indian subcontinent, and the ways in which it is inextricably knotted up with Hindu and Buddhist history, Intizar Husain’s stories derive their structural design and their thematic content from the story-within-story tradition of the Mahabharata, Katha Sarit Sagar, the Jatakas, The Arabian Nights, and the Islamic Folktales. A thoroughly modern writer, he uses them to reflect upon religious faith and identity, home and exile, historical truth and the endless failures of reason in our times.

Intizar Husain in The Beacon

Thus, he uses the Buddhist Jatakas to show how difficult it is in the present to act righteously in the public realm. In the Jatakas the good is unambiguously located in the Bodhisattava, and is available from generation to generation. The monks in the Jatakas, even those with limited intelligence, can easily recognize the Bodhisattava and follow his example. The monks in Intizar Husain’s stories, however, are like the refugees — baffled exiles far from home and unsure of the path to take. They can recite their religious texts but they do not know how to act so that moral or political perfection is the end result of all their striving. At the end, like many a refugee in the partition stories, they merely give up their quest for the good and remain perplexed till the end:

“They had forgotten when they had left their homes or for how long they had been tossed in the middle of those thundering waters.

‘Shall we ever go back?’

‘Where?’

‘To our homes.’

‘Our homes?’

They were bewildered and anxious once again. Home. The very thought of home threatened to shatter their sanity just as the storm threatens to uproot trees…They had forgotten when they had left their homes or for how long they had been floating like leaves in the middle of the vast body of water.”

5

“The word Swaraj is a sacred word, a Vedic word, meaning self-rule and self restraint and not freedom from all restraints which ‘independence’ often means” (Gandhi in his paper Young India 19 March,1931).

The one person who understood that nostalgia, when it confronts hate and murder, can be paralyzing, and that prayer is not sufficient to heal the grievous wounds of the partition, was Mahatma Gandhi. He made a courageous effort to think about the moral consequences of the partition and the ways of rebuilding a civilisational home again – a home he called ‘swaraj’.

Since, colonialism was for him a form of ‘homelessness’, a kind of moral and political wilderness, it is not surprising that he felt that by demanding a religious division of the country, by wrecking its civilisational integrity, we had failed once more in ‘founding’ our home.

As the partition violence increased, he found himself isolated and humiliated. At his daily prayer meetings, he sometimes talked to people whose entire life-world was ruined and at other times was confronted by people who had committed unspeakable acts of brutality and were not repentant. He must have felt a great loneliness and despondency as he walked through the refugee camps and heard people snarl invectives at him and call for his death. He endured his loneliness and despondency by reminding himself that the first and strangest lesson a satyagrahi must learn, and learn repeatedly throughout his life, is that people are reckless when it comes to violating every moral law, but never brave enough when they have to resist evil. Yet, as if to add to the accumulating ironies about the partition, the same people who had thrown stones at him and had refused to let him conduct his prayer meetings also urged him to help them find ways of making a home for themselves again; to help them recover their sense of fair judgment and compassion again.

The advice Gandhi gave them was based on few minimum and non-negotiable religious and political assumptions. His first and most important assertion was that it is impossible for anyone to imagine a god, any god, who did not, under every circumstance, urge the good and forbid all that was cruel, violent and ugly. In the midst of carnage, he told them that they must first understand that “God is good.” Goodness, he said, is not an attribute of God. Rather “Goodness is God.” Then, expanding his radical lexicon, he added that, “God is life” and, therefore, it was imperative for them to protect and nurture life wherever it flourished. He insisted that unless they understood his formulations about god as ‘good’ and as ‘life’ in their radical simplicity they would never be able to rebuild their shattered homes again.

At his prayer meetings, when people demanded that he should not chant the word ‘Allah’, Gandhi told them that the different cognates of the word ‘God’ had the power to disarm sectarian rage and rid the soul of all that is mean and irrational. He understood that they had suffered grievously. He knew they were anxious to build their homes again. Yet, he insisted, one’s home can never be a place which cherished only their particular god. It must be a place, instead, which the gods cherish because human beings inhabit it; a place which the gods seek because the good abides within its walls. Gandhi’s idea that people can never inhabit a home which they have grabbed from others by force because the good no longer shelters there is exemplified in various fictional texts as well.

For instance, in Ahmad Nadeem Qasmi’s story, “Parmeshwar Singh,” a Sikh family, fleeing from Lahore, finds refuge in Amritsar in a house once owned by Muslims. The family is troubled by the sense that every evening strange shadows slip out of the corners of the house and recite verses from the Koran. In Lahore they had lived in the vicinity of a mosque, and the morning prayer had been part of the harmony of their ordinary lives. Now they are terrified and the muezzin’s call sounds like a scream. Instead of feeling at home, they feel trapped in a nightmare. Things change only after they recognise that, as participants in mob violence, they are as guilty of evil towards others as those whom they blame for their present suffering. Recognising his moral fault, Parmeshwar Singh risks the wrath of the Sikh priests and decides that the Muslim boy he has saved from being killed by the mob of which he had been a part, must not be converted to Sikhism. He thinks that it is his duty, instead, to take the boy to his parents now in Pakistan. In doing so he gives up the bigotry of institutionalised religiosity and the self-righteousness of the vengeful. As wrath is defeated by pity, he begins to understand that the assurance of safety to the innocent is “the first requisite of true religion” (Gandhi). He does not forget his own complicity in the atrocities, but having acted according to the principles of justice at last, he is ready to begin the process of making for himself and his family a home again.

Also Read Plays From a Fractured Land: Edited by Atamjit

The idea of the partition may have carried fine intimations of telos for the religious and political ideologue. For the fiction writers, in India and Pakistan, who based themselves on ordinary and common experiences, however, it was nothing more than a mean, ungenerous and grotesquely inaccurate idea of separate and religiously-defined civilisational habitats. The partition shattered all our assumptions about what constituted our Indian identity. It left us with the difficult task of learning to define ourselves again; of reexamining the interpretations of our history to see if we had been terribly misled about our religious character; of looking at old stories which we had accepted as truthful representations of who we were and would continue to be, so as to find out if they had been so fatally flawed that they could only have led to tragedy. The first thing we did, in the Indian part of the subcontinent at least, was to firmly refuse to call ourselves a Hindu nation state (with similar attempts by many in Pakistan to oppose the formation of a theocratic state). There were, of course, voices of dissent, and a Hindu fanatic assassinated Mahatma Gandhi for having betrayed Hinduism. Yet, as a State, we refused to concede that Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and others were strangers to each other; that they were separate pilgrims in the world who were fated to move along utterly different paths oblivious of each others presence. Instead, we reasserted that members of the different communities and sects shared the same spaces and made their human way together through the same history. Indeed, our conviction was that it was their lives together, for good or ill, that constituted us as a civilisation. It was this radical refusal to give up our pluralistic character, which made us call ourselves a secular and a democratic state.

This declaration was the only possible political articulation of our civil and social character in modern times. In a society of such diversities, how could we have possibly asked anyone to surrender his or her rational, moral, ethnic or religious self to any one group, one morality, and one version of holiness?

I am not suggesting that in the process we became a just society. We obviously did not. I am, however, saying that we self-consciously recognized what was required, given our historical past, if we aspired to become a good civilization.

Alok Bhalla is a literary critic, poet, translator and editor based in New Delhi

Alok Bhalla in The Beacon

Leave a Reply