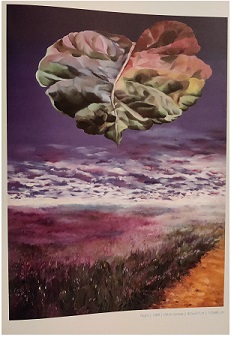

Image of painting by Surya Prakash

Intizar Husain

(Translated from Urdu by Alok Bhalla with Vishwamitter Adil)

H

e went back to the same lane the next day. He knocked at the same door. The same woman with soft feet opened the door and stood before him. His eyes lowered, he held out his bowl for alms. When he received the food, he left. That was the rule of the bhikshus.

He had received alms from countless women at countless doors, but he had never raised his eyes to look at them. He knew that, of all the five senses, the eye was the most vulnerable to sin. The eye, easily enchanted by the beauty of the world, led man astray. A man who was caught in the net of maya suffered. It was the eye that deceived. The wise man, therefore, kept his eyes shut, refused to be deceived and so saved himself from suffering. That was why he never raised his eyes to see whose hands gave him alms.

Even at the door he didn’t lift his eyes to look at the face of the woman who received him everyday. He only saw a pair of soft feet come to the door for a moment and then disappear.

After the first day, he went back to that door the next day and the day after. He went back to it again and again. The woman always gave him alms with great reverence.

It was basant panchami. Yellow sarees fluttered in the breeze in every house, in every lane. It was as if mustard flowers had blossomed in the lanes instead of the fields, and marigolds had filled the houses with their fragrance.

That day he knocked at the same door once again. The same woman with soft feet came to the door again. But that day her feet were painted with mehndi. With his eyes lowered, he looked at those feet and was astonished to see how beautiful mehndi looked on fair feet. The feet of that woman, with mehndi designs, were like works of art. He stared at them as if in a trance. He forgot to beg for alms.

“Bhikshuji, please hurry up! It’s a festival day today.”

He had never heard her voice before. As he lifted his bowl for alms, he couldn’t resist lifting his eyes. And then he couldn’t lower them again. He was fascinated by the beauty of that woman. Her face was like the moon, her hair was dark like rain clouds, her eyes were like the eyes of a doe, her neck was graceful like that of a peacock, her breasts were like ripe pears, her hips were heavy, her waist was slender, her saree was yellow like the flowers of the mustard and she wore a red bindi on her forehead. He was so enchanted that he gazed at her without being conscious of anything else around him.

The woman was shocked. The plate, full of food, slipped from her hand and fell to the ground.

On that sacred day, Sanjaya returned to his monastery with an empty bowl. He was very perturbed.

“Have I fallen in love?” he wondered.

He thought for a long time, but he remained confused. It was as if he had lost his reason. Finally, he went to Ananda and said, “Prabhu, I am very perturbed.”

Ananda looked at him searchingly and asked, “Why?”

“Because of a woman.”

“A woman?”

“Yes, a woman.” Then Sanjaya told him his sad story.

Ananda stared at Sanjaya in surprise as he narrated his tale. Then he closed his eyes and remained silent for some time. After a while he opened his eyes and said, “Bandhu, city streets and houses spread before us nets of attachment. The rule for a bhikshu is that he should wander from street to street and from door to door. One day he should ask for alms at one house, the next day at another. O fool, you didn’t obey that rule. You did exactly what Sundersamudra did.”

“What did Sundersamudra do?”

“Don’t you know what he did?”

“No, Prabhu, I don’t know what he did.”

Then Ananda told Sanjaya the story of Sundersamudra.

The Story of Sundersamudra

It was Janamashtami. The night was lovely and the stars twinkled amidst the clouds in the sky. An old man and an old woman sat in the darkness of their haveli weeping bitterly.

A dancing girl, who was passing by, stopped and asked them in surprise, “Why are you weeping so bitterly? What misfortune has befallen you? On Janamashtami day, when every man, woman and child is full of joyous celebration, why do you sit here shedding tears?”

They replied sorrowfully, “Oh, we’ll never celebrate Janamashtami or Holi or Diwali again! We have lost our son. Every moment of our lives reminds us of him. We can do nothing but weep.”

“You have lost your son!”

“Yes, we had only one son. We have lost him. Now there is nothing but darkness for us in this world.”

“How did you lose him?”

“One day, Lord Buddha walked through this town. The sermon he preached so influenced our son that he gave up his life of pleasure, shaved his head, put on yellow robes and joined the disciples of the Sakyamuni.”

“What is your son’s name?”

“Sundersamudra.”

“I’ll bring him back.”

“You don’t know what you are saying, woman! Has a follower of the Sakyamuni ever returned?”

Annoyed, the dancing girl said, “If he is a muni of one kind, I am a muni of another kind.”

She made inquiries about the Sakyamuni, discovered the name of the town where he was staying and found out where the bhikshus went to beg for food. She went to the same town and rented a large haveli there.

Sundersamudra used to go to that town every day with his bowl to beg for alms. He wandered from lane to lane begging. One day he happened to pass through the lane in which the dancing girl had rented a haveli. The dancing girl had, of course, been on the lookout for him. She went to the door herself with a plate full of food. She talked so sweetly while she gave him alms that Sundersamudra went back to her lane the next day and stood in front of the door of her house.

He became so attached to that house that he stopped wandering from lane to lane. He would go and stand before her door every day and leave with a bowl full of food.

One day, the dancing girl cleverly suggested, “Bhikshuji, if the rules of your order permit, why don’t you stay here today and eat your food. My home will be blessed and will be filled with the radiance of the four moons.”

Sundersamudra thought for a while and then said to himself, “Tathagata never turned down anyone’s request. He didn’t even refuse to eat meat when a fool offered it to him. I, too, should follow the same principle of action.”

So, that day Sundersamudra sat in the verandah of the dancing girl’s house and ate his food. The following day the dancing girl made the same request and once again Sundersamudra accepted her invitation. Well, Sundersamudra began to sit in that verandah every day to eat his food.

Having persuaded Sundersamudra to eat in the verandah of her house, the dancing girl bribed the children of the lane to scream and shout near her house the moment the bhikshu sat down to eat his food.

“Raise a lot of noise and dust,” she urged them. “I shall pretend to be angry and scold you. But you should refuse to obey me.”

The next day the children did as they had been asked to. The dancing girl shouted at them angrily, but they turned a deaf ear to all she said.

When Sundersamudra sat down to eat his food, the dancing girl stood before him with folded hands and said, “Prabhu, the children of the lane are very naughty. They make a lot of noise and raise a lot of dust, and they don’t let you eat in peace. I would be deeply honoured if you were to come inside.”

Sundersamudra once again recalled the Buddha’s principles of action and quietly accepted the dancing girl’s invitation. From that day onwards, Sundersamudra began to eat his food inside the house.

When he sat down to eat, the dancing girl served him with great reverence. But while she waited on him, she did not fail to reveal her charms and graces. How very graceful she was and how very beautiful! Her face was fair, her cheeks were like ripe pomegranates, her plaited hair swayed with the sensuousness of a snake, her eyebrows were arched like two bows, her breasts were round and full, her waist was slim, and her hips heavy. Whenever Sundersamudra glanced at her, he began to feel weak with desire.

The all-knowing and wise Tathagata soon realized that one of his bhikshus was in trouble. Those days Tathagata was living with the monks of his order in Ananthapandaka’s garden on the outskirts of Sravasthi. He called all the monks of his order together to listen to a sermon. When they had all gathered together, Tathagata sat cross-legged under a mango tree with his eyes shut. After some time he opened his eyes and gazed at the assembled monks. Full of wisdom and compassion, he examined Sundersamudra’s face. He looked steadily at him for a while and asked, “Sundersamudra, why is your heart so perturbed?”

Bowing his head, Sundersamudra stammered, “O Tathagata, I have formed an attachment.”

Tathagata continued to gaze at him and said, “Attachment causes suffering. Desire ruins man. Even those monkeys, who understood the dangers of enchantment and desire and turned away from it, are superior to men who long for worldly pleasure.”

Curious, the bhikshus asked, “Tathagata, who were those good monkeys and where did they live?”

“Haven’t you heard the story of the good monkeys?”

The Jataka Tale of the Good Monkeys

Years and years ago, far from the realms of man, in a forest at the foothills of the Himalayas, lived a large troop of monkeys. One day it so happened that a hunter wandered into the forest. After much effort, he managed to trap one of the monkeys. He took that monkey to Benaras and offered him to the King as a gift.

The monkey served the King so faithfully that he was granted his freedom. When he returned home at last, all the other monkeys surrounded him.

“O bandhu,” they cried, “where were you all these days?”

“O bandhu, I was amongst human beings.”

“Amongst human beings! Really? Tell us what they are like.”

“O bandhu, don’t ask me that!”

“But we want to know.”

“All right, if you insist, let me tell you. Like us, human beings are also divided into males and females. The human male, however, has long hair on his chin and the human female has large breasts, so large that they bounce. The female, with large breasts, entices the male with the long beard, traps him in nets of desire, and makes him suffer.”

The monkeys covered their ears with their hands and said, “Enough, bandhu, enough! We have heard enough!”

Then they decided to leave the place where they had heard the tale of evil deeds forever.

Tathagata ended the story and fell silent. Then, a while later, he said, “O bhikshus, I was the monkey who told that tale and you were the monkeys who heard it.”

Surprised, one of the bhikshus asked, “O Tathagata, how do women make men suffer? Aren’t men stronger and women weaker?”

Tathagata said, “O innocent ones! So what if women are physically weaker. They are far cleverer than men and can disarm them easily. Haven’t you heard the Jataka tale about the clever princess?”

“No, Tathagata.”

![]()

Image of painting by Surya Prakash

The Jataka Tale about the Clever Princess

A long, long time ago, the King of Benaras went to Taxila to acquire knowledge. He became very learned and very wise.

The King had a daughter. He looked after her with loving care and guarded her with great zeal. He didn’t want her to fall into bad ways. But a woman, even if she is locked up behind seven doors, cannot be prevented from doing mischief.

Despite all the King’s precautions, the Princess caught the eye of a singer. The palace, however, was so well guarded that the Princess and the singer could never meet each other.

The singer confessed to his old maid-servant that he was in love with the Princess. He persuaded her to go to the palace and become the maid of the Princess. She waited for the right moment to give the singer’s message to the princess.

One day, as the maid was combing the hair of the Princess and searching for lice, she deliberately scratched the Princess’ head with her nails. Familiar with the tricks of enticement and love, the Princess at once guessed that the maid had a secret message for her.

She said, “Arrey, why don’t you give me his message. Speak!”

The maid took courage and said, “He wants to know how the two of you can meet.”

The Princess replied, “What’s so difficult about that! Tell him — a trained elephant, a dark and cloudy night, and a gentle wrist.”

The maid gave the message to the singer. He, too, was experienced at the game and understood the message at once.

He trained an elephant and persuaded a young boy to help him. Then one night, when the skies were covered with the dark monsoon clouds, he mounted his elephant, asked the boy to sit next to him, and waited for the Princess below the palace walls.

That night, the Princess declared to the King, “Maharaj, the rain tonight is delightful. I want to bathe in it.”

The King tried in vain to dissuade her. But the Princess insisted on going out into the dark night to bathe in the rain. She walked up to the parapet of the wall below which the singer was waiting for her on his elephant.

The King, once again, protested, but to no avail. So he followed her out onto the terrace to keep an eye on her. When she began to disrobe, he averted his gaze, but did not let go of her wrist.

The Princess, however, was far too clever for the King. She pretended that she needed both her hands to unlace her dress and urged the King to release her wrist for a moment. At once, she placed the wrist of the boy in the King’s hand and jumped down to meet the singer waiting for her on his elephant. They disappeared into the night.

In the darkness, the King didn’t guess that he had been fooled. He continued to stand with his face averted, holding the wrist of the boy. After a while, his face still turned away, he walked back to the palace. He pushed the boy into his daughter’s room without realizing his mistake, and locked it from the outside.

Only the next morning did he learn that the Princess had eloped with the singer. The King admitted defeat and confessed that it was impossible to guard a woman. “She can vanish even as you are holding her wrist!”

After he had finished the tale, Tathagata sat for a long while in silence. Then he said, “O bhikshus, do you know who that King was? I was the King and had occupied the throne of Benaras in one of my previous births. That Princess was my daughter.”

Then after a pause, he added, “I could decipher the mysteries of nature, but I could never understand the wiles of a woman.”

Sundersamudra suddenly woke up as if from a trance. He realized how dangerous the beauty of a woman could be and resolved to free himself from the trap of the dancing girl. He promised that he would go and tell her never to wait for him again.

When he reached the house of the dancing girl that day, she greeted him with reverence and, as usual, invited him into her house.

That day she had persuaded the children of the lane to shout and play on the veranda of her haveli. She scolded them, but they refused to pay any attention to her. Then the dancing girl stood with folded hands before Sundersamudra and begged, “Bhikshuji, these children are naughty and cannot be dissuaded from playing on the verandah. They will tease and disturb you. So, please come upstairs and eat your food in peace.”

Sundersamudra hesitated at first. Then he said to himself, “People are like children. Their wishes ought to be fulfilled. That is the Buddhist principle of action. Besides, I shall never eat food in this house again. Who knows where I’ll be tomorrow and who will own this haveli?”

So, he stood up and followed her upstairs. As he climbed one step at a time, he kept his eyes lowered. He didn’t pay attention to the woman walking ahead of him. But the dancing girl, who was leading the way, sometimes stopped suddenly as if she was tired. Each time she did so, Sundersamudra bumped into her soft and sensuous body.

When they reached the terrace, she made Sundersamudra sit in an alcove decorated with flowers. Then, pretending that the climb had tired her, she sat down near him.

O bandhu, a woman knows at least forty tricks to entrap a man! The dancing girl knew all of them well! First she yawned and raised her bare arms above her head. Then she suddenly felt shy and lowered them with a coy smile. Then she looked at her nails and played with her fingers. Then she took the end of her saree between her teeth and blushed. Then, for no reason at all, she giggled uncontrollably. Then, immediately afterwards, she covered her face with her hands. Then she spoke loudly. Then she whispered softly.

At first, as if shy, she sat at a distance from Sundersamudra. Soon, she moved up close to him. Once she let the end of her saree slip down her breasts, only to quickly pick it up again and cover herself. Once she lifted her saree to reveal her legs and then quickly pulled it down again. Later she arched her body so far back that her clothes burst open to reveal her breasts, but she hurriedly covered herself up again. Once she leaned so close to him that her lips almost touched his, but she shyly drew back again.

O bandhu, Sundersamudra was completely bewitched! He forgot that he was a bhikshu. She was already burning with passion, and when she saw that he couldn’t resist her anymore, that shameless woman tore off all her clothes and pulled off Sundersamudra’s clothes too. They hugged each other. Their bodies pressed against each other, their limbs twined around each other, they…

Suddenly, Ananda fell silent.

Sanjaya asked, with a tremor in his voice, “What happened next?”

“What happened?” Ananda laughed and said, “Tathagata saw everything from where he sat under a tree. He saw what that shameless woman was doing to one of his bhikshus in an alcove decorated with flowers in a haveli in Sravasthi. Their bodies were about to dissolve into one another, when Amitabha appeared before Sundersamudra in a vision. At once, Sundersamudra came to his senses. He was saved from being drowned in the river of desire.”

Ananda fell silent.

Sanjaya thought for a while and sighed, “Those were indeed blissful years when Tathagata lived in our midst. He could always lead a man, who was enchanted by a woman, back to the path of duty and truth.”

After a brief pause, he asked, “Who will now save me from the deceptive charms of a woman?”

Ananda said, “I will give you the same advice that Amitabha gave me. He said — Ananda, henceforth, you must be your own guiding lamp.”

When Sanjaya heard that, he thought for a while and then said, “I shall be my own guiding lamp.”

So, the next day, as he left for the town with his begging bowl, he vowed to himself that he would not go to the lane in which that woman lived. But when he reached the town, he noticed that every path led to her lane. No matter which path he took, he felt that it turned back to that lane and led to the door of her house. He stopped walking and stood in thought for a while.

How small Sravasthi seemed that day! He knew every lane and alley of that town. He had begged in each lane, he had asked for alms at each door. But that day he saw only one lane and one door, where she stood waiting for him with a plate full of food. He tried to think of the other lanes in the town. To his surprise, he realized that the lanes of the town were spread before him like a net. And that in every lane there were doors at which women stood with plates full of food for the monks who begged for alms. Lanes, doors, women. He reminded himself that they were all nets of maya. Then he recalled the story of the good monkeys who had not only plugged their ears when they had heard about the deceptive charms of women, but had also left the place where they had first heard the story of sin.

“I should also leave this town,” he told himself.

Then Sanjay turned his back on the town and walked towards the forest. Soon he left all the lanes, doors and women behind. He wandered through thick and lonely forests.

One day, he came across an ashoka tree in bloom. He stopped under its shade and sat down to meditate.

It was the season of basant again. The mustard fields were full of yellow flowers. Marigold flowers had filled the air with their fragrance. The ashoka tree was so laden with leaves and flowers that its branches almost touched the ground.

When Sanjaya saw the beauty of the world around him, his heart was filled with ecstasy. He gazed at the ashoka tree for a long time. Then, in astonishment, he said, “O God, is this ashoka tree so full of flowers because a woman injured it?” Soon, he was attracted by the beauty and delicacy of some mehndi bushes near by. “Did those mehndi bushes, so lovely and delicate, inspire that ashoka tree?” It was then that the image of that beautiful woman in a yellow saree rose before his eyes. Spellbound, he gazed at the vision for a long time. When he recovered consciousness, he said to himself with a start, “I am, once again, trapped in the nets of desire.”

He got up and said, “I had sinful dreams under this tree. I must leave this spot at once.”

Sanjaya went on a long journey again. He wandered aimlessly through many forests. Days passed, years went by, flowers blossomed and seasons changed. Each season brought with it its own splendour, its own delight, and then vanished. Each season caused Sanjaya pain. Each season stirred the river of memories and left traces of sorrow. The fields of yellow mustard flowers, the air trembling with music, the sweet smell of mangoes, the swift wings of butterflies, the hum of the slow bee over honeyed flowers, the call of the koel heavy with grief, the fragrance of the champak tree, the sad jingle of bells on a dancer’s feet. Every moment reminded him of the world he had left behind. And the image of that beautiful woman stood before him always.

Sanjaya began to wonder if every path, in every wild forest, led back to her door. He thought about it for a long time and concluded that the seasons were in secret league with the guardians of the five senses, and that the five senses invited suffering. He also concluded that a man could get trapped in the nets of desire in a number of ways. When he touched a soft petal or heard a gentle tune, when he was carried away on the wings of some delicate fragrance or was enraptured by a gorgeous colour. The truth was that every thing in the world could cause sorrow. When Sanjaya realized this, he was very sad. In his grief he said, “There are lanes in a town and seasons in a forest. How can I escape the net of desire?”

Sanjaya was still deep in thought when the leaves turned yellow and began to fall. The days became sad. Dried, yellow leaves lay scattered everywhere. With every gust of the wind more leaves fell from the branches of trees and scattered across the earth.

“What is the significance of this season? Why do leaves turn yellow and fall?” Sanjaya once again plunged into deep thought.

Slowly, a dim memory of something he had heard a long time ago began to stir in his mind and excite him. He recalled a story which was entirely different from his own.

The season was the same, the forest was similar. Tathagata had chosen to begin his meditations when yellow leaves lay scattered on the ground. He picked up a handful of leaves, turned to Ananda and said, “Ananda, have I gathered all the leaves of the forest in my hand?”

Ananda replied, after some hesitation, “O Tathagata, in this season all the trees in the forest shed their leaves. There are infinite leaves scattered on the floor of the forest. Who can count them?”

Tathagata had replied, “Ananda, you have spoken the truth. I have picked up only a handful of leaves. The same is true of all that we know. I have only preached as much Truth as I could gather in my hands. Like the leaves scattered on the earth, Truth is also infinite.”

The recollection of that story had such a strangely profound effect on Sanjaya. He stood rooted to that spot for a long time. After a while he sat down, cross-legged in the posture of meditation, under the shade of a peepal tree which was still covered with the splendour of leaves. He began to meditate on the season when the leaves turn yellow and fall, leaves that were infinite like the Truth. He watched them fall in astonishment. Then, slowly, very slowly, he shut his eyes. “That which is outside me is also within me,” he said to himself.

His eyes shut, he sat in meditation for a very long time. He meditated for days, for years. When he opened his eyes, he realized that countless seasons had passed and that the leaves were falling again. This time his lap was full of dry, yellow leaves. His body had been bathed by a shower of yellow leaves and burnt dry by the heat of the sun. He raised his eyes and saw that the peepal tree was now completely bare. Then he looked all around him. As far as the eye could see, the earth was covered with yellow leaves, and as far as the eye could see, the branches of the trees in the forest were bare.

He looked into his own heart and said, “I too have shed all my desires. They are now like these yellow leaves.”

After a long pause, he said, “All seasons pass. Basant, winter, the monsoon. Flowers wither, perfumes scatter in the breeze, trees shrivel, but the season when the leaves turn yellow and fall returns eternally.”

Then his face lit up with a smile. He felt as if his hands were full. He stood up. He was now at peace.

He said to himself, “My search has come to an end. I should go back.”

Sanjaya entered the forest, his heart despondent and his mind disturbed. He left the forest, his heart full of compassion and his soul at peace.

He walked out of the forest and went back to the town.

Sravasthi echoed with festive mirth that day. The town had been transformed into a gorgeous garden. The air was heavy with perfume, the lanes were gaily decorated. Birds sang, flowers swayed in the breeze, women wandered through the lanes in sarees of fascinating hues.

For a moment Sanjaya thought that he should stand in the middle of the town and preach, “O ignorant men, O dwellers of Sravasthi, don’t lose yourselves in the pleasures of the senses. Flowers wither, perfumes scatter in the breeze, beauty fades, and youthful bodies sag. The seasons of beauty do not last forever. Only the season, when the leaves turn yellow and fall, returns eternally.” But then he realized how completely detached he felt from all that he saw around him. He felt no desire to speak.

He lowered his eyes and walked in silence through the streets of Sravasthi. He didn’t raise his eyes even once to see where he was, before whose door he stood with his begging bowl. “Why should I look up?” he asked himself. “My purpose is to receive alms. Why should a monk bother about where he receives them, at which door and from whose hands?”

His lowered eyes fell on the feet of the woman who gave him alms. He was startled. He saw the same fair and soft feet decorated with mehndi.

“Is she the same woman?” He looked up in surprise and saw her standing before him. She had not changed. He remembered her in the same yellow saree, with the same red bindi on her forehead and the same plate full of food in her hands. He couldn’t lower his eyes. He couldn’t move. He stood as if in a trance.

In that one moment ages and ages seemed to have gone by. It seemed to him as if she had stood, generation after generation and birth after birth, at the same door and in the same manner; and that he had stood, generation after generation and birth after birth, before her, gazing at her in amazement.

Once again, his thoughts were troubled, his soul sorrowful. The season began to change. The trees grew strong and small green leaves appeared on dry branches. Full of doubt, he looked into his soul and asked, “Have new leaves sprouted within me too?” Puzzled, he asked himself again, “I followed the light of my own lamp. Where has it brought me? What leaves are these that I hold in my hands now?”

******

Notes Original title: Patey. Date of publication: 1990

Alok Bhalla is a literary critic, poet, translator and editor based in New Delhi

For the Love of the Earth: A Note on Surya Prakash’s Paintings

By

Alok Bhalla

The paintings of Surya Prakash (1940-2019), an eminent painter from Hyderabad, can be divided into very distinctive phases. His early and youthful work was entirely devoted to painting sites of industrial accidents and waste — primarily crumpled cars abandoned in open spaces. At one stage, however, he made a sudden and radical decision to turn his gaze away from the images of man-made disasters to meditating upon nature to try to find there sources of grace and peace; nature in all its phases – when it was dry and the earth was cracked or when there was rain and even rocky land began to burst with life (for a while he trained under the great artist Ram Kumar when he was painting his landscapes of Varanasi). It is this second phase, during which Surya found a distinctively personal visual idiom and a developed highly sophisticated craft, which brought him professional recognition and personal calm. He never again painted human forms and their sorrows; never again pay attention to the fatigue of the social world or the bitterness of competitive politics; nothing that belongs to our world of flint and steel or can be expressed by hard geometric designs and sharp tense lines (contrast his work with that of his contemporary, Vivan Sunderam’s dark and threatening emergency series with their black hole and instruments of violence or the brutal Machu Picchu prints). Henceforth, (under the deepening influence of Monet, Seurat and Cezanne) his canvases were calm, gentle, and utterly serene lyrics about the simple and elementary things in the natural world: lotus floating on lake waters, leaves falling over sunlit landscapes, shadows floating across hills and flowers, rocks andthe rustle of water.

Having watched the second phase of Surya’s work over a long period of time, I can assert that Surya was one of those rare and gifted modern Indian painters who was in love with the earth as a place of loveliness and delight, of well-being and trustworthiness (the other painter with whose paintings one can compare Surya’s to is J. Swaminathan with their ochre rocks, blue skies and peacocks). Each canvas of his, which records the shades of beauty that lay around him, is an act of homage and an expression of gratitude to the land around where he lived (Hyderabad in the 1970s and 80’s, especially around Banjara and Jubilee Hills, was not yet the brutal and polluted place it has now become). There is in each object he paints a translucence of colours and an exuberance of forms; a luminosity and an enchantment; a confident coming into being of things and their silent disappearance. His paintings are, perhaps, like the dreams that wander through the of minds the arhant who, as the books of sacred lore say, are granted the boon of joy and creativity (I can only think of Mac Chagall’s dream world in comparison that is as magically expansive. The difference is that in Chagall’s paintings human beings, nature and angels seems to be engaged in an eternal dance even as the world around seems to fraught with pain). Surya’s paintings create non-violent spaces in which there is an endless play between the red-rust glow of sunsets and the shades of yellow that spread across fading leaves; where a rich variety of greens weave and fuse their way into an infinity of things in the universe. Surya does not seek to explain the things he paints nor does he look for a purpose and meaning in their existence. He is a non-egotistic painter who accepts without anxiety that stones, leaves, morning light, hills, rippling circles in water are things which are simply given. For him it is the very ‘presentness’ of such things which makes the earth a place of glory (a glory which is so grievously threatened). Indeed, watching his paintings reminds me of the Zen master who, when asked if the visible tree was real, replied it was, and when further asked, in what way it was real, replied that ‘it was real in every way’ (Intizar Husain’s Bhikshu in “Leaves” is in search of precisely this kind of answer which he must arrive at in his ownway).

It is not surprising that Surya Prakash’s canvasses create a sense of flatness of space so as not to give any object or shape a place of privilege even as he lays layer after layer of paint till each colour acquires its unique luster. There is no contention between the shapes he paints or the colour he uses. Further, every shape that is painted seems like only a partial unfolding of its essential form, its mysterious essence which has yet to reveal itself, a delightful moment in the peaceful processes which defines our lives. That is, perhaps, why no single colour draws exclusive and dazzling attention to itself. There is a profusion of colours whose presence and place is decided, not by the formal laws of symmetry and chromatic value, but by the free impulse of the imagination (there being no symmetry or geometry in nature). Each colour reveals its rich tonal variety and blends into other strong, elemental colours. Reds and yellows and blues and greens swirl and flourish around one another, flow and slide into each other and so create, as if out of their own energic abundance, variety and beauty. Each painting by Surya Prakash restores to us our ancient, lost sense of the earth as place of change and play, mortality and delight.

Leave a Reply