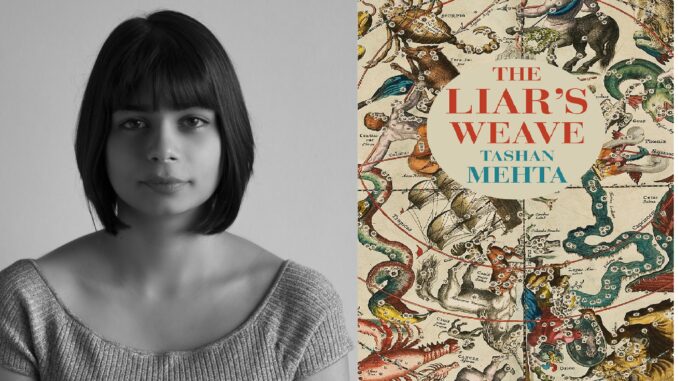

Tarun K. Saint with Tashan Mehta

Tarun K Saint–Which writers left a key imprint on your sensibility as you decided to become a writer? Were writers like Ursula Le Guin and Philip K. Dick and those writing in the fantastical tradition like Borges and Calvino crucial, or did you draw on readings from the sub-continental epics and Indian fantasy writings? Can one speak of a hybrid set of influences for you personally?

Tashan Mehta— Italo Calvino has been hugely influential, although I discovered just how much only after I wrote The Liar’s Weave. His Six Memos for the Next Millennium is fantastic, especially the chapters on lightness and quickness. I recommend them highly for any writer. U. K. Le Guin is also instrumental—she gives you this permission to reimagine what literature might be for and where it may belong, permission that’s important for all writers to hold close and to use.

The Latin American magic realists also played a big role in the formation of my writing—Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Mario Vargas Llosa, Julio Cortázar. Hilary Mantel as well; historical writing has a lot in common with speculative fiction: you’re trying to recreate a world for the reader that they’re unfamiliar with and you’re trying to keep it both strange and intimate. No one does it as well as Hilary Mantel.

I also drew a lot of joy from Gerald Durrell when I was younger, especially My Family and Other Animals. Recreating that joy in people was the primary motivator for becoming a writer (it has, sadly, changed since then). I’ll wrap up this list now, otherwise I could go on forever, but John Le Carré as well: The Constant Gardener was my first taste of a literary novel that didn’t seem to perform or preen. It was as true to the material and the heart of the book; it lived.

So yes, I definitely think one can speak of hybrid influences. As a writer, you pull from whatever you can to make the story walk and talk and live, from every genre.

TKS– Your debut novel The Liar’s Weave appeared in 2017. The novel explores an alternate history diverging significantly from history as we know it. Were there particular models that you had in mind (such as The Man in the High Castle, by Philip K. Dick)?

TM— I do remember being very much in love with Man in the High Castle when I read it in university, but Philip K Dick was doing far more complex things with our relationship to history than The Liar’s Weave. The primary influences for The Liar’s Weave were the magic realists, specifically Marquez and Cortázar. They do this see-saw between the fantastic and the real where you can’t really tell where you’re standing, the real or the fantastic. I love that liminal space. How does the reader feel when pushed into it? How urgent does the fantastic become when it could be reality? I wanted to see what that felt like when the reality was mine.

TKS-There is no nexus event that leads to a divergence (say like Hitler winning WW2) in the novel. The experience of the Parsi protagonist Zahan Merchant who is born without a future, unlike his compatriots, who live lives determined by birth charts, is unique. He is also endowed with the power to change reality with his lies. Give us a sense of how you conceptualized this scenario, with its specific rules and moral conundrums.

TM— Ah, it was tricky. The book was born from a short story where a man could change reality with his lies. When I decided to expand it into a novel, friends pointed out that there needed to be a limit to his power—otherwise, what’s to stop him lying about being king of the world? I was very grumpy with the feedback, but they were, of course, right and it led me to the driving conflict of the novel. Zahan can’t see his own lies; reality doesn’t change for him.

After that, it was just a lot of excel sheets, diagrams, long conversations with anyone who would listen about the mechanics of it, and trying to keep it all straight in my head as I wrote the different drafts. It began with only one rule, but as the world expanded and that one rule met with different scenarios, it grew more complex. That’s how you get to that chapter in the book, near the end, where three or four rules intersect into a reveal. It was crazy, and it was fun; I was very much discovering as I went along. I wouldn’t do it again though; my head hurts just thinking about it.

TKS–The parallel universe in your novel does have its intersections with recognizable moments in history such as the nationalist movement. How important were such occasional congruence and joining of fantasy world-building and the flow of ‘ordinary’ reality?

TM— Less important in the final book but hugely important in an early draft. There was a thread of the novel about how Zahan’s power influences the freedom movement. I axed it in the end—the novel was already growing too large for me to handle, and I wasn’t sure I could do it justice. Several readers have sensed the ghost of that ambition, though, which makes me think I should have just deep-dived into it.

TKS– The vidroha movement in the forest brings in an off-centre, subaltern perspective. However, ambiguities come to the fore as Zahan gets entangled with this group. Can fantasy become an effective vehicle for exploring the fraught situation of disempowered groups? Does this bring the narrative closer to Rushdie-style magical realism?

TM— I think fantasy and speculative fiction are immensely powerful tools for exploring the realities of disenfranchised groups. The speculative has the power to make readers see things anew, from that slightly askew angle, and can provide fresh perspective on a reality they may not particularly want to look at, even if the information is available to them or they’ve gleaned the basics of it.

Interestingly, Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children wasn’t an influence for The Liar’s Weave. He brings a political verisimilitude and realism—a glut of hard-hitting, anchored detail, in a way—that The Liar’s Weave is far from manifesting. If I was to pick the book’s closest companions/inspirations, it would be U. K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed or—although I hadn’t read it when I wrote The Liar’s Weave—Prayaag Akbar’s Leila. Neither is as fantastical as The Liar’s Weave, but they’re both exploring power and powerlessness and what our characters do when they’re on one side of the line and then the other.

TKS— Your forthcoming story ‘The Traveller’ (in the second Gollancz Volume of South Asian SF) takes forward the experimentation with form seen in your novel. Dreams can be seen to transform perceptions and real world manifestations here. Was Le Guin’s The Lathe of Heaven a palpable source of inspiration while writing this story?

TM— It wasn’t, but now I have a new Le Guin to add to my list—thank you! I wrote “The Traveller” from this desire to push the speculative as far into the subjective and the abstract as I could, while still anchoring the reader. How clearly can imagined worlds manifest notions and concepts we commonly describe as “feelings” or “instincts” or even as “indescribable”? For example, if you took a list of what being Indian feels like to me—jugaad, fluid, more “find the gaps” than “follow a path,” instinctive, organic, capable of a reality beyond logic—and manifested that in the literal world, how would the mechanics of it work? And what happens to a traveller who lands on its shores, but is made from a whole different set of concepts and notions?

TKS– Let us know a bit about work in progress, including forthcoming books and stories. Is SFF/speculative fiction likely to be your preferred mode of expression?

TM– Speculative fiction is definitely my preferred mode of expression, although I think the degree of speculative is likely to differ. After writing The Liar’s Weave, I grew interested in alternate worlds built on different assumptions than ours. This, coupled with my new interest in the many shapes of madness, has influenced the short stories I’ve written and the novel I just completed. I have a short story upcoming in Third Eye Anthology about a world where each person experiences a different type of time; it should be out by the end of the year.

I also worked on an experimental project for the Barbican, where I conceptualized and wrote a piece that captured the feeling of a multi-disciplinary residency I was part of. I loved that process; it allowed me to put doubt at the center of the work, a sort of “I don’t know” even from an authorial standpoint, and I want to try a lot more of those. I worked with the designer to create the “artefact” as well, and seeing how the physicality of the book can shape the reader’s experience was lovely. I am working a novella now along those lines.

Alok Bhalla–is writing serious SFF basing oneself in societies (or communities) which are fundamentally religious and superstitious more of a challenge? One can, of course, write SF as a dark satire about such communities in the manner of Swift’s Voyage to Laputa or, perhaps look back with nostalgia from a late 3045 BC about a distant past when Hanuman could fly and carry back a mountain for a magical herb (Incidentally, the Black Panther movies do something similar by imagining pre-colonial Africans with Shamans). Even a brilliant novel like The Overstory, by Richard Powers, has difficulty with the Indian (Hindu, of course!) computer geek in some future time who whines about Indian gods even as he creates complex modules. What kind of social structure did you imagine in your novel, The Liar’s Weave?

TM— The social structure in The Liar’s Weave was relatively simple: I designed it around the main conceit—everyone’s future is known—and the groups created by that assumption. So we have the power-holders (the astrologers), the unfortunate who drew the worst futures (the hatadaiva), and everyone else, trying to live ordinary lives within the confines of that conceit. What drew me to the idea was creating a world as similar to 1920s India as possible. It’s that liminal space I mentioned—I wanted that feeling of what if this could happen? What would it feel like for me?

Religion and superstition worked in my favor in this book, mainly because the idea is based around something that exists—birth charts. It created a platform in reality for me to launch from, and thus take the reader along. That’s largely why foreign audiences struggle withThe Liar’s Weave: they don’t have that platform, and they’re constantly struggling with what’s the secondary world and what’s the primary one.

AB— One of the crucial problems that has troubled SF writers from the time of Frankenstein onwards is that of imagining human love (and sexuality) in future time. Human love is either monstrous or impossible. Think of Karl Capek’s RUR or Ishiguru’sNever Let Me Go, where love as a sentiment important for the survival of our future becomes unimaginable. In Chris Marker’s great film, La Jettee, the man trapped in a dark authoritarian future travels back in time only to realise heartrendingly that love is now only a fading memory. In Tarkovsky’s haunting version of Solaris, the protagonist understands that love in future time can only be the love for simulacra. To what extent did your speculations about alternate identity constructs encompass the realm of love/eroticism while writing The Liar’s Weave or after?

TM— Love was central to my imagining of these alternate selves because it is a core of what makes us human, and an interesting facet of power and powerlessness. Because it’s so integral to being human though, it wasn’t tricky to imagine. There’s no erotic love in The Liar’s Weave—they’re all very chaste, very hilariously pure characters—but there is romantic love (Tarachand and Parineeta), brotherly love (Sorab and Zahan), and what was the driver of the novel at one point, the love between parent and child (Zahan and his mother).

Tarachand and Parineeta were a convenient way to look at how this world of the novel—your future being known and choice erased—would work on a romantic love you didn’t want to give up. Sorab and Zahan were the bond driving the novel: how far do you go for the person you love, even to the point of driving yourself mad? And the third kind of love was the most interesting, because what happens when a mother doesn’t love a child in a way that is traditionally expected? How does that drive the child, and how does it affect the relationship? Those three loves were all consequences of the questions I was asking, and the ways in which the characters act out their humanness. Part of the fun of writing The Liar’s Weave was creating speculative elements that pushed those loves to the brink and beyond.

AB/TKS-In the subcontinent, ghost stories about the superstitious past have had a conservative dimension, perhaps due to fear of change. Has contemporary speculative fiction, including your work, become a vehicle for making more sharply critical statements about present day dilemmas, whether in the domain of religion, ecology, gender relations or politics, eluding the traps of informal and formal censorship in the process?

TM-I think we’ve eluded censorship for now, but it’s likely on its way. Speculative fiction from India is definitely doing smart and engaging things with the issues we’re facing, but its generative power is bound to be noticed at some point, not only by those reading and listening to what is being said, but by those who dislike the narratives being created.

That being said, censorship is not here yet and I hope it won’t happen. There’s real power to this genre. It’s what U. K. Le Guin meant, isn’t it, when she asked us to “imagine new alternatives”? That we could. It’s an acceptance of the power of the idea, of showing the reader new ways of looking such that they see their reality as clearly as possible, warts and all, just as they see all the ways in which it could be different. Indian spec-fic has harnessed this, I think, and I can’t wait to see how it engages with this promise of new alternatives as it evolves as a space.

**

RULEBOOK FOR CREATING A UNIVERSE

Tashan Mehta

In an island that floats at the beginning of time, there is a Rulebook for Creating a Universe. This book is old, with instructions on how to make forever-worlds. It says, ‘When stitching a universe, think carefully about the kind of sun you want. Will it be hot or cold, moss or vein? Your sun will last forever and your planetary colour palettes will depend on it. Choose wisely. Follow the blueprint.’

Beloved, you know this story.

You know Yukti is a weaver on this island-before-time and she hates weaving. Her mother must put the lotus stalk in her hand and even then she will scowl at the water until her mother says, Faster Mu-mu, we don’t own time! So Yukti – who also hates the nickname Mu-mu – will snap open the stalk to reveal filaments of silver that she thinks look like spit. These are the fibres of Time. She will rub them together to make a thread and begin stitching the banana leaf she is assigned.

This is how a single universe is made – on this island, one leaf at a time. Leaves make a tree. Trees and rivers make a planet, planets create a galaxy, and galaxies form a universe. Small to large.This is what Yukti’s mother tells her as she brushes her daughter’s hair at night. She wants Yukti to apply herself. We’re doing good work, Mu-mu. Her daughter leans back into her chest, happy. Are you listening to me? Her daughter shakes her head, giggling. You’re not listening to me, you shaitan. Her mother tickles her until Yukti squeals.

On days her mother takes pity on her, Yukti is sent to harvest the lotuses. This she loves. She’s the only girl on the boat but she belongs – even the men know it. They send her into the thick patches of lotuses, where the boat cannot push its nose, and she wades among petals as large as her torso. The water, which is biting cold, grows warmer when she clutches a lotus stem, then hot when she holds the slippery knife and hacks through it.

Her brother tells her, in conspiratorial whispers, that this is because the lotuses go all the way down to the beginning of time.

But there is nothing in her life until now, nothing really, that explains why the lotuses one day bend their heads and begin talking to her.

Yukti doesn’t understand the lotuses’ language. It is colour that blooms across her mind, the scent of faint perfume, trails of thought that writhe and curl like reeds. It changes her. One day she blinks and the island dissipates, breaking into a zillion fine particles of gold dust. She blinks again and the world coalesces, regrowing its outlines. She trembles.

She begins to dream of volcanoes.

She doesn’t know what a volcano is. They’ve never made one on this island. She tries to describe it to her brother and he tells her that she means a melted sun, that’s all. So she starts thinking of suns.

Apoi, why can’t we make suns?

Her best friend Apoi puts down the fern she is stitching and thinks. They are sitting on a platform that floats on the endless water of their island. Water and lotuses, that’s all their island-before-time is made of. Apoi thinks hard. It is not a normal question; no one here asks these things. But Apoi is the best student in the village and so she finds an answer.

Because suns are big and require strength, she explains. Boys are stronger. Girls have deft fingers and so can stitch forests and rivers.

Yukti wasn’t looking for the textbook version. We can do it too, she says, surly but under her breath. Apoi doesn’t hear.

The Rulebook for Creating a Universetalks about the lotuses. It says, ‘Beware. Lotuses may shimmer and turn to gold dust when you hold them. Ignore this. Hold fast and cut the stalk as low as you can reach. If the lotuses talk, don’t listen. Never listen.’

Yukti has listened.

Ma?

Yes, Mu-mu?

Why don’t you make suns?

Her mother stops stirring her lotus stew. She is more perceptive than Apoi, so she says, Why do you ask?

But Yukti knows this sidestepping tactic. Have you tried? she asks. She doesn’t know that her voice is growing shriller, as it does when she is upset.

No, her mother says gently. But—

Why not? Aggressive now.

Because I don’t want to. Her mother continues stirring her stew, deciding that the best way to deal with this tantrum is to ignore it.

I don’t believe you.

Yukti— Stern now.

I don’t believe you. And if you had tried, only tried, then maybe I could stitch them too!

Yukti is sent to bed without supper. She lies on her mat and feels her skin boil, itching to erupt. She is filled with a bottomless want; she wants to know who decided the things she could and could not do; she wants to scream. The lotus voices whisper.

Later, when her mother kneels by her mat and asks if she wants her hair brushed, Yukti says no with venom. Then she cries into her mother’s lap, with large heaving sobs, as her mother strokes her hair soothingly.

They stop Yukti going out with the boats.

Her mother tries to hide her madness from the village but they learn of it. Yukti is now seeing three of everything. She is saying nonsense words in her sleep. The elders meet and remember the teachings of their ancestors. They have an important task here on this island – they are responsible for all creation. Each task in their society has been carefully crafted to fulfil this purpose of building universes; each person must play their role. A girl must never go to the lotus fields – it only spreads disaster.

The elders visit Yukti’s family. They tell her father to mind his daughter; they comfort Yukti’s mother, who trembles at what Yukti may become.

That night, after the elders leave, her mother makes lotus tea. She sits alone in the dark,steeping over the problem.

She knows her baby better than anyone else. The elders think the problem is small, some vague babbling,but she knows how far it has gone. Her daughter’s eyes are seeing further than they are meant to see. Her grandmother got like that once. They blinded her in fear.

She cannot let that happen to her baby.

From then on, she watches Yukti like a hawk. She makes her weave on a cushion opposite her, in her shadow; if Yukti goes to play, she follows. Her brother is forbidden to tell his sister folktales; her husband is made to wash all trace of lotuses off him before entering the house.

Yukti doesn’t complain.

Instead, she weaves better. She stops talking in her sleep and smiles when she’s supposed to, even though the smile doesn’t reach her eyes. Once, her mother catches her drawing a mountain with a hollow inside,but when she blinks Yukti has rubbed the drawing away – and she doesn’t know if she imagined it.

She must have.

Yukti becomes the best weaver in the village. She is praised; neighbours drop inat the house to admire her work and stay till they are offered free tea. Yukti’s mother pretends to be proud. She thinks of the hollow mountain and wishes her daughter’s smile would reach her eyes.

Then, one day, Yukti glances up from the glow lamp as she kneels beside her mat and looks – really looks – at her mother. Yukti’s eyes are wide, as large as the day her mother gave birth to her. Then she says Ma and holds out her arms.

Her mother collapses into them. She holds her daughter close, pressing her nose into her daughter’s neck, breathing in. When Yukti pulls away and smiles, it reaches her eyes.

That night Yukti’s mother brushes her hair slowly and languidly. They drink lotus tea. They laugh, warm in their love for each other. Then, when the sky is covered with gold-black, Yukti slips out of her mat, past her sleeping family who dream dreams of content, down the stairs and into the cold, where she unties the boat from its moorings and slips it, eel-like, into the catfish-black water.

You know where she is going.

The Rulebook for Creating a Universe talks a lot about the lotuses. It has 547 rules on the flowers, all of them warnings. Rule 89 is in bold. It says, ‘You are not a hero. Lotuses seduce. You are not immune to that seduction. Stay humble and work with the group. Stitch with direction, with the softness of certainty. Never stray.’

The water is emptier than Yukti remembers. Across each mile of glass, she sees the ghosts of lotuses now cut; their dead forms leave gold dust in the air. Yukti knows she is the only one who can see this, just like she is the only one who notices that the stalks the boats bring are yellow. The lotuses are dying. The village is farming too far and too fast; Time is running out.

She wishes her mother could see.

When the lotuses appear, they do so suddenly; Yukti is dwarfed by their petals, each flower eager to touch her skin. They are happy; they have been waiting for her. Her boat is nosed forward with trembling lotus pads; petal tips play with her hair. She laughs. She feels alive, understood. All her fear disappears.

The boat comes to a halt. Yukti waits. Nothing happens. The lotuses watch her. She watches them. Gold dust floats as if on the breath of an invisible creature.

Yukti grows sleepy and leans against the side of the boat. Gently, almost listlessly, she dips her fingers in—

—The water erupts. Gold fans out in all directions; something wraps around her wrist and yanks her in. She thrashes, panicked, but more stems curl around her legs and arms. She fights. She opens her mouth to say please, but water pours down her gullet; the lake closes over her head with a wooosh. The last thing she sees is the lotuses, hazy through the water. They look hungry.

In the beginning, there were ideas. They streamed through the void as gold particles, content to go nowhere. Then similar ideas began to coalesce. They moved out of the neat lines they followed and clustered into logical order – this idea first, that particle second, and so on. In this way, they made Time.

These threads spun themselves into an island, floating in the void. They curled into seeds and became lotuses so that they could open their faces to the void, feel its cool touch. They wanted to have faces. They called to their brothers and sisters still journeying across the void; they asked them to join the island and feel what it was to be. Several did. They rained down and melted and bumped into the lake you now drown in. They even made you, bronze-skinned and yellow-eyed. They gave you only one command: make. But you listened wrong.

Why are you telling me this? Yukti asks.

She is floating in water that is golden, green and blue in different shimmers, like it cannot make up its mind. She isn’t breathing, so she must be dead. But the heart of the island is staring at her like she is anything but.

Why did you come to us? the heart asks.

Yukti doesn’t know how to translate her yearning into the lotuses’ language. She wants to burst out of her skin and flower into a jungle so complex no one could weave it. So instead she says, You are dying.

You heard wrong, the heart says. When did we ask you to snap us open and weave with our innards? What use is dead Time to you, silver like old hair? You were meant to shape the void as we shaped you – by tilting your head to the sky and listening to where the ideas wanted to go. When did you grow deaf?

Yukti wakes because she has to vomit. She vomits and vomits, emptying all the water in her. Then she curls up on the boat’s smooth belly and waits for morning. When it comes, she holds the paddle in her shivering hand and rows home. It takes her longer because she’s tired and the paddle keeps slipping from her grip. When she pulls into the village, it is almost afternoon.

Her community watches her. They discovered Yukti was missing in the middle of the night; her brother raised the alarm. When her mother found the boat gone, her heart sank. But by then it was too late.

The village’s activities lie abandoned; the villagers stand, grave, at the edges of their stilted houses. Yukti can see Apoi, her eyes like petrified pebbles, her mouth forming a similar o. Yukti doesn’t stop; she rows until she reaches her house. When she climbs the stairs slowly, she finds her mother waiting for her. When she dips through the doorway, her mother backs up against the wall, frightened.

In the house’s cool interior, Yukti realizes why. She is glowing.

Mu-mu?

Yukti nods.

Where were you, Mu-mu?Her mother takes a step forward. This girl is her baby, her beloved baby who kept trying to eat her thumb when she born and who laughs like a drunken man, in great big hiccupping hiccups. She will not be scared of her.

Yukti tells her. She knows she must go to the elders with this story but she wants to tell her mother. Besides, she is only fourteen and her parents are still an authority of a sort, even though it is not spelt with a capital A.

So she describes how universes are being built with dead Time, spinning suns that cannot die and so do not truly live. Nothing will change in those galaxies; trees will not grow or shed leaves; rivers will not swell or fade. Mountains will always know only one height – the height the villagers gave them. In time, the dye will fade to reveal the silver weave from which the worlds were made; then this too will grow pale, caking into white ash. Creation will spin with burnt remains, until these too will flake and be swallowed by the void.

Her mother closes her eyes. Her child is mad.

So Yukti shows her. She unfurls the hand she’s kept clutched this whole time to reveal a lotus bud, its petals parted in a surprised and embarrassed breath, its roots intact. She lifts it to her lips and blows. Gold dust settles into her mother’s eyes.

Beloved, you have been in this story. Versions of it play across time, on loop. It’s in your bones.

So, remember. Breathe through your fear and pull up the strands of this story. The elders will not listen. There’s Yukti, clutching onto her mother as they pull her away. She’s frightened, confused. She’s telling them what they cannot see; she’s only trying to save them. Why won’t they listen?

She finds no answer. Her mother is hysterical. She’s fighting with the villagers, trying to get to her child. She’s saying, It’s only make-believe, she doesn’t mean it, she takes it back, she takes it back. Yukti’s father is shouting. Yukti’s brother tries to reach his parents and finds the crowd shrinks away from him, like he is diseased.

Yukti looks for Apoi in the pandemonium, the smartest person in the village, the best student. You have to listen to them, she shouts, hoping her best friend can hear her. She will understand. You have to let it become.

Apoi looks away.

After that, Yukti stops fighting. They drag her out.

Yukti is branded hysterical. Her mother is blamed for this new epidemic of lotus madness. Her father is disciplined, her brother ostracized. If you look closely, you can see her mother’s eyes grow hard in a way that scares Yukti’s father. You can hear the echoes of Yukti’s last words as they tie her to a boat, rippling in the still air. Listen – why won’t you listen?

Fear hardens.

The community pulls together. Scribes draft the Rulebook for Creating a Universe. Artists sketch the first official blueprint. Copies are made. Keepers are appointed. The Rulebook is taught in special schools. Children quiz children on its details, a game. Girls who stitch leaves make sure they copy the veins exactly. Precision is praised.

And Yukti, the girl who won’t stop glowing, is locked in a house built specially for her, far away from the village. She is left to starve. But she doesn’t starve. She eats the gold dust she can scoop from the water by thrusting her hands into the gap in the floor. She listens to her heart shrink until she believes it cannot get any smaller. She stares out of the window as the lotus fields dwindle. They’re crying out for her help. She has nothing left to give.

All this is the story.

Now remember the parts they don’t tell you.

Like how everything is built like a volcano – planets, universes, bodies – with molten change sitting in our bellies. How the lock on Yukti’s jail clicks one night and the door pops open. How five women stand in the doorway, carved by the amber moon. A silhouette of a lotus flower, now fully grown and its roots trailing the floor, hangs from one of their hands.

Some things, Yukti’s mother says as she presses her daughter to her chest and they cry with an emotion that cannot be held in language, can only be done in silence, at night.

Six women stand waist deep in empty water. Gold whirls around them. Yukti turns to her mother, her glow faint now, and says in a small voice, I don’t know what to do.

But her mother is having none of it. She runs her fingers through Yukti’s hair, feeling the strands knot between her knuckles. Her baby. You only have to listen, she says. Her voice is so sure and full of love. It steadies Yukti.

Yukti takes a deep breath and closes her eyes.

They build a universe out of gold dust, collecting in their palms from the water. The particles flock to them, eager. The women shape with their fingers, asking the particles which ones they would like to join with.

Yukti’s yearning fills her. It mixes with her fear and her hope. Who knows what tomorrow will bring? Shemay never see another light orget this chance again. So she crumbles her fear and gives in to her yearning, letting it rise in her like a moltenwave. She pours it into the universe she’s shaping. When the particles in her hand begin to vibrate, she knows they will never be content to stay in a single sequence.

The women weave small and fine and tight, so that when they are done, the whole universe sits on Yukti’s palm, no bigger than a gold speck. Clutching it very gently in her nails, Yukti pulls her arm back as far as it will go. She flings the speck into the void, where it disappears.

The Rulebook for Creating a Universe mentions Yukti only once. It does not take her name. It says, ‘Remember the girl who tried to steal Time to weave a universe. Remember that in her universe suns die and they call god a woman. Do not let that be your daughter.’

Yukti’s seed, pushed deep into the void’s skin, will burst. It will carry colours of its own. The particles in it will link and dissolve and link again into formations that will burn our eyes when viewed through our telescopes. It will create mountains that crush us and ocean depths we cannot touch. It will spiral up and down and up, the dunes of existence. We will keep trying to cross them.

It will have volcanoes.

But let us leave grandeur to science. Let us leave language to itself. Get up and go into the sun, beloved, to the edge of a world that houses you. You are on a beach. You’ve spent the morning scared of a future you cannot predict. You’ve spent the afternoon trying to map out different possibilities to create a rulebook of your own. You’ve prayed to this universe for the only thing it cannot give you: Certainty.

Now let it go. Breathe in the salt. Watch the gold glint on the crest of a wave.

Then walk to where the crabs make their maps and the sea tries to drown them. Let a wave recede and press your toe into the wet sand it leaves behind. Watch it erupt into gold.

This is your inheritance. Listen.

*******

Tashan Mehta is a novelist whose interest lies in form and the fantastical, and how a dialogue between these elements may offer us collective ways of seeing. Her debut novel, The Liar’s Weave, was shortlisted for the Prabha Khaitan Woman's Voice Award and her short stories have been published in several anthologies. She was part of the Sangam House International Writers' Residency (India) and was British Council Writer-in-Residence at Anglia Ruskin University (United Kingdom). You can find out more about her at tashanmehta.com.

Dialogues with South Asian SF Writers in The Beacon

Leave a Reply