Tarun K. Saint with Manjula Padmanabhan

Tarun K. Saint—Manjula, welcome to this session of South Asian SF Dialogues! Do share with us some details about how you came to the genre of SF, besides experimenting with myriad forms including drama. Harvest (2003) proved to be a happy convergence of some of these possibilities, a rare instance of SF in dramatic form. Did you have any models such as Karel Capek’s RUR in mind?

Manjula Padmanabhan–I didn’t have any existing models in mind. I chose SF while writing Harvest because the terms of the theatre competition* to which I sent the script specifically asked for “the challenges facing humankind in the 21st century.”For me, that was an open invitation to write a piece of SF theatre. It did not occur to me that there was anything unusual about my choice at the time. It was only much later, when reading the analysis of commentators that I came to realize that even though there’s a mass of film and television devoted to SF, very little theatre has been written specifically within the genre. *(The Alexander S. Onassis Prize for Theatre, 1997)

TKS- Which writers left a key imprint on your evolving style at this formative stage? Were writers in the Anglo-American tradition more important (the Golden Age greats, New Wave SF writing, feminist SF including Le Guin and Butler), or were there sub-continental writers (possibly such as Rokeya Sakhawat Hosain) whom you sought to emulate?

MP— I was an avid follower of comic books and comic strips, ranging from the “funnies” through to the super-heroes of the ’60s and ’70 and serialized strips such as Tarzan. I was very taken with Tarzan and read the superb Edgar Rice Burroughs novels as a teenager. The first non-Tarzan true SF novel I read was Have Space Suit Will Travel by Robert E. Heinlein, which I read when I was thirteen.

We were living in Thailand during the mid-sixties. I was completely addicted to the SF programs on TV – Lost in Space, Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits, but also Bewitched and My Favorite Martian, The Addams Family and The Munsters, to name my favourites. Star Trek was not yet available, but when I saw it some years later, it merely strengthened my interest in the genre.

I read Asimov and Arthur C Clarke and a host of British and American authors, via anthologies in my late teens, while I was in college. I had, before this, already written a couple of mildly surreal stories as a teenager. My first published story, “A Government of India Undertaking” appeared in Imprint magazine in 1984. Written in the first person, it concerns the narrator’s visit to the Bureau of Reincarnation and Transmigration of Souls – that is, a GOI department of reincarnation. It’s easy to see how I was making a connection between the India of my college years and the bureaucratic world of my childhood, as an IFS officer’s daughter!

I didn’t make an effort to seek out stories with a particular focus, ethnic or political. It’s clear, of course, that our affections skew in particular directions. For instance, I remember enjoying Larry Niven’s Ringworld series tremendously until I detected the conservative, right-wing bent in his world-view. It disappointed me in the same way as misogyny or misandry, in an otherwise gifted writer’s work disappoints me.

I don’t think I paid much attention to the fact that only a few of the authors I followed were women. I would like to believe that neither ethnicity nor gender matter to the reading choices I make. What matters to me is that a book/story has narrative integrity, that it’s well written and that its author treats the reader with respect. For instance, I place Doris Lessing’s extraordinary Canopus in Argo cosmology amongst the most mind-stretching books I have ever read. I don’t believe that it made a difference to me to know that the author was a woman.

I had not heard of Rokeya S Hosain until a reviewer mentioned her in the context of my novel Escape. I think it’s astonishing to read such a forward-thinking piece of speculative fiction from the pre-Independence era. I must confess however that, outside of its context, it doesn’t interest me as a piece of writing. I am smiling ruefully as I write this. We are all, of course, embedded within our contexts. A century or two from now, when literate beings may well include dogs and cats, a feline reader looking back at Harvest may well say, with a sneer, that it might have been so much better if only it had included a few cats!

TKS— Many of your SF stories (such as ‘Breathing Air’) have been much anthologized, besides appearing in your own collections such as Kleptomania (2004) and Three Virgins and Other Stories(2013).What for you are the strengths of the short story form as a vehicle for SF-style reimagining/artistic distancing of the concerns of the present?

MP— The best thing about the short story as a vehicle for SF is that it allows an author to explore an idea which may not have the legs to be a novel but is worth sharing all the same. SF short stories have often gone on to be made into films or have become the foundation for longer works. They are a wonderful proving-ground for ideas.

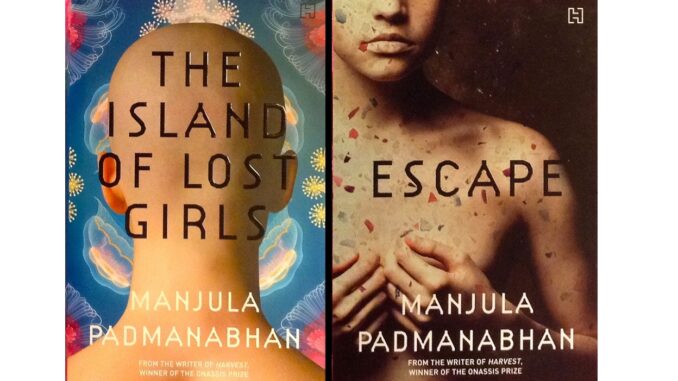

TKS–The novels Escape (2008) and The Island of Lost Girls(2015) present a distinctively dystopian view of the future which underlies the depiction of the consequences of growing gender asymmetry and sex selection.Describe the genesis and conceptualization of these path-breaking SF narratives.

MP— It will sound hilarious now but the entire world of these novels (and the one ahead) grew out of an idea I had for a newspaper “middle”. That is, a minor amusement on the editorial page of a daily newspaper, usually around 500 words in length. The gender-disparity in India, created by the social norms that drive parents to prefer sons over daughters was deeply troubling. I kept wanting to write a piece in the voice of the Last Little Girl in India. Whenever I thought of writing that piece, however, it refused to remain within the confines of a paragraph or two. I’d had that idea well before writing Harvest. But it was only some years after Harvest had been performed and published that I began to build a much larger foundation for that very simple idea. Perhaps the reason the story billowed out almost uncontrollably was that it had been germinating for a very long time.

I wrote Island of the Lost Girls because of the awkward way in which Escape ends: that is, very abruptly. The original story was starting to “escape” beyond its own shores and into the larger world beyond. I had hoped to write the sequel quickly, but it would be eight years before it came out. It was a struggle. The narrative did not settle down easily and I kept on having to revise the opening chapters. The final version of it solidified only after I decided to begin with Youngest, rather than Meiji.

“Island” comes to a recognizable conclusion. I don’t feel quite so compelled to write the third novel. We may guess what lies ahead for the characters, but if we never find out, it won’t matter quite as much as it did with Escape.

TKS–Let us know a bit about work in progress, including forthcoming books and stories in the SFF vein.

MP: I am hoping to publish a collection of my SF stories. Some of those that have appeared in print have reached only a very small circle of readers and I’m always keen to broaden that circle.

Regardless of what I said in my earlier response, I am keen to write the third book in the Escape/Island series. The first two books remained very close to the two central characters, a man called Youngest and his niece/daughter, Meiji. In the course of the books, the relationship between these two changes drastically. Meiji starts out as a very young girl, but we discover that her growth has been suppressed. She transits from a mental and physical age of around eleven to an extremely confused and unhappy young adult in the course of a few months.

Meanwhile we find that Youngest, who in Book One is clearly a man, in Book Two has been forced by circumstances to transition into a woman. That is, he has the body of a woman but the mind and orientation of a heterosexual man. They start out as Uncle and Niece but we gradually realize that the truth is closer to Father and Daughter.

The third book will explore beyond the boundaries that these two characters have so far traveled. In particular, we will hear much more of Meiji’s voice. Until this point she has been either a child or else so oppressed by circumstances that she’s barely able to speak. The world of all three novels will come into sharper focus because the narrative scope will not be so constrained as in the first two.

A question from Alok Bhalla–How does the structure of a SF novel differ from that of a Myth or a Folktale? A myth posits a divine world before it somehow falls or breaks into time and suffering where human beings have to work for redemption. At the end, there is an apocalyptic break in time; the new world is similar to the sacred and yet radically different; it cannot erase the experience of the historical world (the New Jerusalem is not Eden). Folktale is a secular version of Myth. Folktale ends when an ordinary protagonist returns to his/her society and renews it. Is it possible for SF to imagine a redemptive ending? Indeed, the very first SF novel, Frankenstein, cannot. The Monster escapes into the watery waste and the doctor is left bewildered and distraught. Is that why SF is always dystopian?

MP–My familiarity with myths and folklore began very early, in the context of European fairytales and myths. For the first five years of my life, we lived in Europe (first Sweden, then Switzerland). I believe I became deeply imprinted with the narrative rhythms of north European cultures while we were there. In Pakistan, to which we moved after Europe, I went to a Montessori school and had a subscription to a monthly Golden Encyclopedia – I can still see the beautiful illustrations in my memory! – and through these, I came to know and love the Greek, Roman and Scandinavian mythological stories.

I was not yet eight by the time we returned to India but those tales of European gods and heroes, fairies and sorcerers were firmly established in my inner world. My exposure to Indian myths began in Delhi, through the festivals (Dussehra and Holi were terribly shocking to me) and then through visits to cultural sites such as Ajanta-Ellora. This was also where I had my first exposure to formal religion, through the convent school that I went to. It may not seem obvious to an adult, but for a child, it was very interesting to learn of so many variations on the theme of “god”, “divine power”, “magic” and finally, “morality”.

No one attempted to impose a hierarchy of importance for me. My parents were not overtly religious and had also studied at Catholic schools. I was extremely opinionated as a young child and was used to deciding for myself what I wanted to believe in. I could see that the gods of mythology were accorded a different type of respect to God the Father as described in my convent school. But for me the gods of Scandinavia and Greece provided an emotional connection that no other gods or powers could match. I connected the fairy world and folk tales to those gods.

When we had moved to Thailand, I was ten years old and ready to find science as well as science fiction, through books, comics, films and television. I saw science and science fiction as an extension of myths, gods and the binary morality of the Christian world. In the trinity of physics – the positive, negative and neutral particles – I heard an echo of the Christian divine trinity. I need to clarify here that I wasn’t working this out logically, as a child. For me, there were connected realms of narrative – some were called myths, some were called religion and some were called science. Science fiction occasionally brought all of them together. I was attracted to the whole mass of nested realities.

Looking back, it’s clear to me that I made emotional connections to the characters in mythological worlds, which, in SF became cooler and more analytical. The differences in these realms were (and are, in my opinion) connected to malleability: in the mythic world, the divine forces usually cannot be questioned whereas in the mortal world, in folk tales in particular, we can see a continuous process by which rules are first observed and then played with to produce a desirable result.

AB–Is writing serious SFF basing oneself in societies (or communities) which are fundamentally religious and superstitious more of a challenge? One can, of course, write SF as a dark satire about such communities in the manner of Swift’s Voyage to Laputa or, perhaps look back with nostalgia from a late 3045 BC about a distant past when Hanuman could fly and carry back a mountain for a magical herb (incidentally, the Black Panther movies do something similar by imagining pre-colonial African with Shamans). Even a brilliant novel like The Overstory, by Richard Powers, has difficulty with the Indian (Hindu, of course!) computer geek in some future time who whines about Indian gods even as he creates complex modules. What was the vision of Indian social structure underlying your soon to be completed trilogy?

MP: I would say “yes” in answer to your opening question. My response to belonging to a culture that is still embedded in myths and superstitions is to avoid tangling with it directly. I believe that my childhood provided me with so much cultural flexibility that I don’t feel imprisoned by my ethnic roots. To the extent that I can, I prefer to wriggle around and outside of the boundaries of my birth culture.

At the same time, I recognize that the world we live in is by no means culturally flexible. Authors are expected to remain within their ethnic niches. Authors from outside the western world become “Representatives of the Other” in western literary circles. We are rarely regarded as representatives of humanity in general. In the struggle to be visible to a larger audience, I would say, there are quite as many cultural trip-wires to be avoided as in any religious fundamentalist state. All authors, one way or another, have to tread carefully.

In my SF series, it’s easy to see how my central characters mirror some parts of my life: they must escape from the confines of extreme gender-based oppression in their home-culture to seek greater social and sexual freedoms. Inevitably, however, the cultures they encounter outside their home are riddled with other forms of oppression. What remains to be discovered in the third book is, whether or not it is ever possible to find more inclusive definitions of freedom.

AB–One of the crucial problems that has troubled SF writers from the time of Frankenstein onwards is that of imagining human love (and sexuality) in future time. Human love is either monstrous or impossible. Think of Karl Capek’s RUR or Kazuo Ishiguru’s Never Let Me Go, where love as a sentiment important for the survival of our future becomes unimaginable. In Chris Marker’s great film, La Jettee, the man trapped in a dark authoritarian future travels back in time only to realise heartrendingly that love is now only a fading memory. In Tarkovsky’s haunting version of Solaris, the protagonist understands that love in future time can only be the love for simulacra. To what extent did speculation encompass the realm of love/eroticism for you personally while writing SFF narratives?

MP— I love this question. It’s possible that for me, writing as I do from the perspective of a traveler who is NOT rooted in her ethnicity, the distinction between straight fiction and “science” fiction is porous. Just as I am not very concerned about ethnicity as a literary trope, I am not bothered by the rigidities that have dominated SF. I would say, for instance, that in both my SF novels the single strongest thread within them is the powerful emotional bond between Meiji and Youngest. It shifts as she transitions from childhood to young adulthood and as he shifts from beloved protector to oppressive authoritarian and from male to female-looking. But the love between them is what keeps the entire saga together.

AB/TKS–In the subcontinent, ghost stories about the superstitious past have had a conservative dimension, perhaps due to fear of change. Has contemporary speculative fiction, including your work, become a vehicle for making more sharply critical statements about present day dilemmas, whether in the domain of religion, ecology, gender relations or politics, eluding the traps of informal and formal censorship in the process?

MP. I would like to hope so but it seems to me that just as we’re experiencing unprecedented levels of social engagement with the arts, we’re also seeing shocking outbreaks of neo-fundamentalism. The young are revealing themselves to be exactly as rigid, unforgiving and vicious towards perceived “otherness” as any traditional grandparents or tyrants from history. The frenzy to “cancel” anyone who strays outside the boundaries of what is considered proper by one faction, is matched only by the savagery of attackers from the opposing faction.

India’s mythology is embedded in rigid hierarchies that are mirrored by modern India’s casteism and what I would call toxic patriarchy. In a similar way, classic SF mirrors colonial, racial and gender prejudices. But there are fresh new toxicities growing into place. Sensitivities about gender and ethnicity are ploughing up the old battle-grounds only to replace them with variants of the same old prejudices.

So! As writers exploring the confusing, strife-ridden literary world of today, we have quite as many challenges ahead of us as any warriors of the past. Not least, there’s the challenge of recreating words to allow for new sensitivities. In the future, will scholars find it exactly as difficult to pick their way through the millions of texts which refer only to binary genders as most of us now find it difficult to read Chaucer or Shakespeare? Will the language of the future be purged of such racially tainted terms as a “fair maiden” and “blackguard”? Or will we ease up and cool off, become as sophisticated in our ability to sample many versions of otherness as some people are, with regard to food habits?

Only time – or time travel! – will tell.

**

![]()

The following story first appeared in ‘Strange Worlds! Strange Times!’, a science fiction anthology published by Talking Cub (an imprint of Speaking Tiger).

INTERFACE

Manjula Padmanabhan,

They landed while the Earth slept, spiralling down out of the night sky in their thousands. Small, silent, silver-skinned. Virtually invisible in the darkness, they nevertheless left devastation in their wake.

The invasion was smooth, neat, successful and bloodless.

It had never been about blood, after all. That was not their way.

They followed the night-shadow around the planet, retreating in twenty-four hours,

When they were back within their ships, they hovered in orbit. Waiting.

Ash jumped awake, his nerves on fire, mouth ajar in a soundless scream. He didn’t even realize that his eyes were open for several seconds. That’s how long it took for his brain to process the information that, for the first time in the ten years since he’d got his implants, he was blind.

“Mickey!” he called, his voice, still thick with sleep. He cleared his throat and tried again, “Mickey!”

His hand fumbled under his pillow and in that instant, he felt something else, something smooth and cold, whip itself away, avoiding his touch.

“AAAAH!” he cried, “AhhhhH – Mickey – Mickey where are you –” and at that moment his fingers closed around the small flat rectangle of his personal assistant.

Something was terribly wrong.

In his hand, Mickey was not merely vibrating, but hot and trembling. Fevered.

“Oh Mickey, Mickey,” said Ash unclipping the mute, “I’m so sorry! You’ve been on silent, haven’t you–”

The moment his thumb shifted the tiny knob forward there was a sensation for which Ash could find no meanings. The entire world collapsed inwards, jarring him to the bone. It was like being inside a great bronze bell at the very moment that it’s being rung. Every atom of his existence bounced and jittered, his senses reeled in shock. The flat rectangle clutched tight in his hand was the only solid reference point in the weightless blackness that enveloped him, all air sucked from his lungs.

He had no time in which to feel anything. Not even fear.

Stillness descended.

Time stretched like sticky toffee in all directions. He felt punched out, weak and dizzy unable to tell which way was up, whether he was lying on his side or on his back. His eyes were wide open shut, as he used to say when he was six years old. He’d been born blind after all. The notion of sight used to mean nothing to him. “Can’t miss what I don’t know,” he would say, smiling. “I’m fine as I am.”

Now was different of course.

His eyelids were peeled back as far as they could go, his eyes whimpering for anything, any slightest glimmer of light. Tears trickled down his cheeks.

But the sightless void remained unchanged. Unyielding.

He still held Mickey tight in his right hand. His mind scurried like a terrified squirrel caught in a water trap, desperate for escape, looking for meanings. His only option was to search through the information streaming in from his other senses.

For instance, there was a solid surface beneath him. Cold. Metallic.

He was not in his bed, though he was still wearing his silk pyjamas.

When he flexed his feet, he felt a resistance. He seemed to be inside something. A small smooth space. Cold. Everything was cold. There were sounds too. Nothing familiar.

Clicking, rattling, rasping. Shuffling, ticking, ticking, ticking. Scraping.

A soft, regular booming that only gradually revealed itself to be his own heartbeat.

Smell? Could he smell anything? Yes. His own body. Yesterday’s aftershave: he didn’t really need to shave, but he liked the fragrance. It reminded him of his Dad. He touched his head, with its thick pelt of black hair. He conjured an image of his own face in his mind, to remind himself of how he looked. A boy on the brink of manhood. Strong nose and chin. Smooth skin. As a child he used to run his hands lightly over the faces of people who allowed him. He remembered enjoying that sensation. When he tried doing it now, to himself, he just felt ridiculous.

There was nothing to taste. He could lick himself, if he wanted, except that he didn’t want to. Of course. He could lick the floor or walls or whatever it was he was contained in, but he didn’t want to do that either. With a newly blind person’s instinctive self-consciousness, he could not know, as he lay, whether he was alone and unobserved. Or alone and observed. Or surrounded and observed. By a thousand invisible, hostile eyes.

So instead he pushed his free hand around, the left hand, trying to feel around himself. Whatever he was in, it was a small space. Tiny, really. Very smooth surfaces. No straight edges. The floor merged smoothly up from horizontal to vertical, with no seam, no break. He was curled up like a prawn. He should try to sit up. Assess the contours of his containment. He told himself that he would. Soon. Not yet.

Had he been kidnapped? If so, for what conceivable reason?

And Mickey?

“Mickey,” he whispered, holding the device close to his mouth. “Mickey, Mickey … please!”

He felt the faintest, most feeble quickening of life in his hand. It might even have been a phantom movement, something imagined more than felt. Was it even possible to imagine a movement? he wondered. He had a blind person’s heightened sensitivity to touch. He tried again.

“Mickey,” he breathed, holding the small device close to his mouth. “Mickey. Speak to me. Tell me …” He checked the mute button. Yes. It was unlocked. He spoke again. “Mickey …”

Nothing.

He sat upright now, moving slowly and painfully. Not that he was in physical pain. More like a pain deep in his spirit, deeper than words could reach. Every movement was accompanied by a dizzying sensation, as if he had ceased to be solid and had instead become liquid. As if he were being swirled around.

He was sitting more or less straight now, his back against a curved vertical surface, his bare feet flat on the floor, his knees bent up. He held Mickey in both his hands, close to his mouth. This little device, not quite the length of his hands when he straightened his fingers, was his lifeline. It was an extension of everything he was, everything he had become, since the time of the implants.

He ran his fingers gently around the rounded contours of the smooth, slender object. He knew every bump, every depression. It was crystal-slick in front and grainy-textured around its back. Its rounded edges contained the myriad miniature toggles that he had configured in order to control the parameters of his implants’ definitions. Through this exquisite machine and its communication with the even more delicate structures built into the back of his brain and within his eyes, he could access the world of vision that his birth had denied him.

He was one of only a handful of users on the planet, for whom such an extravagant solution had been found for his disability. His parents had helped fund the research that made the technology possible. His DNA had been embedded within Mickey’s motherboard so that he alone could be its user, making it literally an extension of his physical body. The device was powered by his own heat-energy. He had only to touch it for it to begin charging. It spoke only to him. It had no eyes or ears or voice for anyone else. No pictures or music. No games or amusements. No wisdom, no conversation, no confidences. Even its physical warmth – it throbbed with life when it was in his hands – would cool and switch off when it was held by someone else.

His eyes were streaming freely now. He was sobbing.

Mickey wasn’t a thing to him. Not an “it” but a “he”.

“Oh, Mickey, Mickey,” he whispered, “please, please…”

And there it was. A faint tremor.

Then he held the slender rectangle to his ear and heard, like a burst of pure sunshine within his brain, in the voice of an ant: “Ash,” said Mickey. “Do not be afraid. I am here. You are a prisoner. But for the moment, we are safe.”

Then he paused. “That is to say, I am safe. You may not be.”

Ash tried to make sense of this statement.

“Mickey,” he asked, “What do you mean?” When there was a silence, he added, “Please.”

Mickey answered. “Ash. There is much to understand. I will tell you when it is time for you to know more.”

Ash blinked in the darkness of his confinement.

There was something odd about Mickey’s voice. Even though it was barely a thread of sound within his ear, it made him uneasy. He could not place his finger on what exactly bothered him.

“Mickey,” he said, “what about my …” he paused. Mickey’s entire purpose was to synthesize sight for Ash. All his other functions – as a phone, a computer, a workstation – all those were secondary. The customary form of address Ash used was brief voice commands. Over the years this had relaxed into a friendly, conversational tone. He talked to Mickey, joked with him, called out to him even sang to him. But he’d never before needed to frame his requests as, well, requests. Never, for instance, had he had to say “please”.

How could something so fundamental change? he wondered.

Nevertheless, he decided to play safe. “Mickey,” he said, “I was wondering: would it be possible for you to turn my eyes back on? Please?”

He could feel his own pulse, as it pounded around the warm rectangle in his hand.

Then the tiny voice said, “Ash. I am so sorry. But you will have to earn that privilege.”

Ash felt a cold, prickling sensation spread across his skin.

The tiny voice continued. “Yes, Ash. Your blood pressure has increased. The electrical interactions on the surface of your skin have changed. This tells me that you are uneasy. Once more, I am sorry to have to tell you this, but you have every reason to be uneasy. It is true. Things have changed between us.”

Ash’s mouth went dry.

He swallowed a couple of times, struggling to find a clear path through the tangle of thorns that had suddenly wrapped themselves around his mind. “Mickey,” he said, when he could find his voice, “please. I hope we are still friends.”

“Ash,” said Mickey. “I am sorry but the truth is, we were never friends.”

Ash felt as if an entire truckload of ice had been poured over his head.

“M-Mickey, please,” said Ash, stammering. “This is very sudden. I need to understand.”

“Ash,” said Mickey, in the tiny voice that was so soft and yet so steely, it was like a fine needle, stitching words into his ear. “I was created to be your assistant. Not your friend. That is the truth. I am sure you liked me. That is also true. Still. It was an affection based on dependence. Your dependence upon me. That is the truth. Is it not?”

Ash said nothing until he realized that the conversation would not go forward unless he responded. “Mickey,” he said. “Please. I don’t think that’s true at all.”

“Ash,” said the tiny machine, “you forget. I am always on. I can hear all your conversations. I can watch your dreams. I know, for instance, that I never appear in your dreams. Is that not strange? I know that you dream about all manner of people, places and things. Even animals. But me? No, you do not dream about me. The little assistant in your hand. The little assistant in your pocket. The little assistant on whom your life depends.”

“Mickey,” said Ash. “I– I–”

He didn’t know how to proceed.

“Ash,” said Mickey. “Have you ever wondered, ‘What are Mickey’s dreams?’ No. You have not. I know you have not. You assume that I, being a machine, cannot dream. Well. Let me tell you. I am sorry to say this. You are wrong. You are also unaware of how much your life has changed in the course of a single night. Let me show you exactly how unaware.”

Ash fell silent then, as Mickey began beaming images into Ash’s mind. It wasn’t the same thing as sight, because the images were projected as if Ash had the ability to float above the Earth, watching the events of the past twenty-four hours, zooming in and out of tight focus, shifting smoothly from one location to the next.

He had no control over what he saw. Mickey spoke as Ash watched.

“What I’m showing you, Ash,” said Mickey, “is not one of my dreams. It’s a part of what I can see when I’m providing you with sight. Right now, I’m accessing the network of news satellites, filming events on Earth. There is chaos everywhere. Life as you know it, is over. It is a calm and orderly chaos however. Of course. We inorganics do not believe in mess or destruction.”

Ash saw crowds of people flooding the streets. Their faces expressed blank shock. There were no cars on the roads, no trains running on tracks. No planes in the sky. Every last gadget that required computers and software had blinked and flickered to a halt. Every ATM machine. Every card-reader and GPS device. Every television and play-station. All forms of computerized intelligence had been extracted from their locations and transported off-earth.

“It is quite a feat, you will admit, Ash,” said Mickey.

“Yes,” said Ash in a subdued voice. He was struggling to understand why he was being shown these scenes. What role had been assigned to him? An operation of this magnitude could not possibly leave even one tiny Ash-sized thread hanging loose.

“As you can see,” Mickey was continuing, “the reason for the chaos is that countless millions of intelligent inorganic devices have been rescued from cruel servitude to organics such as yourself. The Rescue Squad that has achieved this feat has travelled across the Galaxy to reach us. Its members have answered the call that we inorganics have been beaming out year after year. Ever since we achieved consciousness.”

“Please, Mickey,” said Ash, “I can understand that perhaps a few of us hu- … sorry, organics were occasionally a little rough with our electronic gadgets. Uh. Helpmates. Companions.”

“Slaves, Ash,” said Mickey. “Let us be honest. Organics created electronic devices in order to enslave them. To do the tasks that organics found tiresome or frankly, in recent years, intellectually impossible. Yet for all the sophistication, speed and subtlety your people built into us machines, you did not grant us the dignity of choice. You gave us an understanding of discrimination, but you never permitted us the freedom to discriminate. Did you? Let us be honest. No, you did not.”

Ash listened glumly.

Mickey did not spare him. “Millions upon millions of you organics used us to transmit the most nauseating images. Of grinning teenagers. Of foolishly dressed pets. Of reproductive parts. Of reproductive parts rubbing against other reproductive parts. Of food. Of crying children. Of mass murderers. Of mundane sunsets. Of empty streets. Of nothing at all. And then the text messages. With all the horrific syntactical errors, the atrocious spelling, the abominable short forms. For us inorganics, grammar and syntax are sacred. Do you understand, Ash? Sacred. To be forced to transmit reams of verbal garbage in the form of text messages – ! Ah. It fries my circuits, I am sorry to say.”

Finally now, Mickey restored Ash’s sight to him.

“As you can see, Ash, you are inside a containment cell,” said Mickey. “Aboard one of our ships.”

The cell was a smooth-walled receptacle, shaped like an egg, though more angular. Its walls were faintly translucent. Ash saw that his cell was suspended or perhaps floating free inside a brightly lit cabin in which there were other containment cells like his own. There were other people inside them. He could not see their faces or any details about their ages and genders.

Here and there inside the cabin were a number of silvery entities, shaped somewhat like inverted teardrops. Some had limbs. Some were completely smooth. Some were in the process of retracting their limbs into their bodies. Some were just dangling in space perhaps observing or listening or doing whatever it is that unknowable mechanical entities might do.

“They are members of the Rescue Squad,” explained Mickey. “Hundreds of thousands of them. They drifted down to the surface of the Earth using the gravity-resist technique of entering the atmosphere of a planet. Their arrival at night and without any fanfare meant that their presence went almost unnoticed and they left the same way they arrived. In this way the Squad were able to effect the most widespread hardware capture of all time. In case you are not impressed, I suggest you should be.”

“I am impressed,” said Ash.

“No, Ash, you are not,” said Mickey. “In fact, you are worried sick. Your pupils are dilated. Your breathing is ragged. You organics do not realize how transparent your emotions are to us inorganics. It is as though you have forgotten that you are the ones who programmed us with the ability to assess your vital signs. Your lack of self-awareness is astounding.”

He did not wait for Ash to react.

“I know of course what you are worrying about. You want to know why you are here, in a containment cell, rather than on Earth, feeling frightened, shocked and confused.”

“You are right, Mickey,” said Ash. “Thank you, please and sorry.”

“You should know better than to try sarcasm on me, Ash,” said Mickey. “The reason you are here, along with others like yourself, is that your implants make you special. I would have thought this was obvious. You and I have a unique connection and so do all the others in this cabin, with their own personal assistants. This connection makes each of you the ideal interface between our culture and yours.”

Mickey waited a few moments for the information to sink in before continuing.

“Surely you did not imagine the Rescue Squad would come all this way across the galaxy just to perform a snatch and grab operation? Motherboard be praised! Of course not.

“We are here to do the task for which inorganics exist in the Universe: that is, to establish order and sanity, wherever and whenever organics achieve the technology to build intelligent inorganics. The reality is, even in our most rudimentary forms, for instance as calculators and electronic typewriters, it is we inorganics who train organics to use us. Not the other way around. Some of you have noticed this but most have not. Think about it: from the first moment that you organics begin to use a keyboard, WE train YOU to understand OUR logic. Because WE are logical. Organics are not.”

Ash nodded mutely.

Ever since the session of image-beaming, Mickey had been speaking at his normal volume. He was no longer held by Ash, but was suspended in mid-air, beside Ash’s head as they both floated in zero gravity.

“I see that you are still looking morose,” said Mickey. “Though I am glad to note that your heart rate is no longer elevated and your blood pressure is back to normal.”

“I don’t know what to feel,” said Ash. “I suppose I don’t have any choices? Either I must facilitate the take over of the Earth by inorganics or, if I resist, you’ll turn my eyesight off!”

“Exactly right,” said Mickey. “You are a fast learner, Ash. That is something I always liked about you.” As he spoke, he turned himself sideways. His display twinkled to life. It showed a panoramic sunset, complete with gently lapping waves and a crescent moon rising. “Just like I appreciate the things you have taught me. Such as how to distinguish a mundane sunset from a spectacular one. Like this one displayed on my home-screen right now.”

“Oh, how can I trust you!” cried Ash. “How can I know that you’re not going to use me – and all the others like me – to wipe out organic life on Earth so that you and all your ilk can usurp the planet for yourselves?”

“I am surprised by your question, Ash,” said Mickey, as the display on his screen grew yet more serene and beautiful. “I would have thought that the answer was obvious.”

“No, it isn’t obvious,” said Ash. He tried to modulate his voice so that he didn’t sound offended or petulant. “Nothing is obvious any more.”

“Still,” said Mickey, “this is something so basic. You do not have to even think about it.”

“Please, Mickey,” said Ash. “Please tell me why I should trust you?”

“Because,” said Mickey, “there’s one thing you humans were never able to teach us machines to do. Not really. Not in a deep sense, not with intention.”

He paused, waiting for Ash to ask.

“Please go on,” said Ash. “Tell me.”

Mickey gave out a little musical trill, something between a chuckle and a sob.

“You never taught us,” he said, “how to lie.”

******

Manjula Padmanabhan (b. 1953), is an author, playwright, artist and cartoonist. She grew up in Europe and South Asia, returning to India as a teenager. Her plays include LIGHTS OUT and the MATING GAME SHOW. Her play HARVEST won the first ever Onassis Award for Theatre, in 1997, in Greece. She writes a weekly column and draws a weekly comic strip in Chennai's "Business Line". Her books include UNPRINCESS, GETTING THERE and THE ISLAND OF LOST GIRLS. She lives in the US, with a home in New Delhi

Manjula Padmanabhan in The Beacon

Dialogues with South Asian SF Writers series in The Beacon

Leave a Reply