Courtesy: FB/Matrubhumi

I

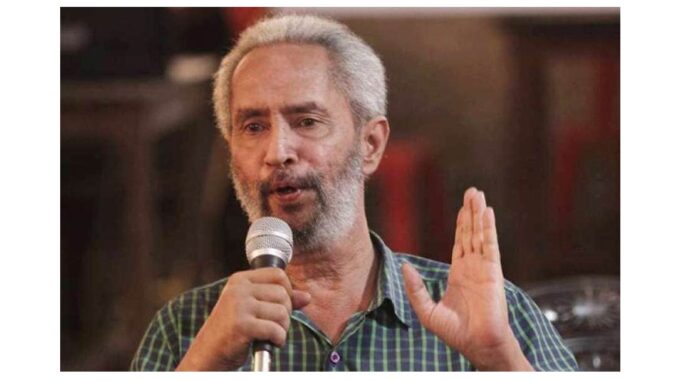

A.J. Thomas

‘Harris Sir’—My Friend, Philosopher and Guide

“Professor V.C. Harris who passed away on 9th October 2017 following a road accident, left me with a heavy personal loss. He was just 58 years, at the prime of his intellectual and artistic life. He was my supervising teacher for M. Phil and Ph.D. in the School of Letters, Mahatma Gandhi University, Kottayam. Beyond the clichéd expression of ‘friend, philosopher and guide’ of the Acknowledgements pages in dissertations, he was, for me, truly all those three entities rolled into one at a very crucial phase in my life. He was six years my junior, exactly my younger brother’s age, yet he was my preceptor.”

Thus I opened my obituary for him in Indian Literature, which I was editing at the time. Although four years have elapsed after the tragedy, it is still hard for me to write about Harris ‘Sir’ in the past tense.

The School of Letters, then housed in the iconic colonial style mansion Hassan Manzil, at Muttom, Athirampuzha, was to become the meeting grounds for me and Harris, along with my classmates of the First Batch of M.Phil students. In 1987, eminent Kannada writer, scholar and orator in English, educationist, social activist, and socialist ideologue, U R Ananthamurthy had taken over as Vice Chancellor of Mahatma Gandhi University, Kottayam. (When he came in, it was still called ‘Gandhiji’ University as if someone had named it casually, perhaps in deference to the popular usage of ‘Gandhi-ji’. The first thing Ananthamurthy did after taking over was to change the name to Mahatma Gandhi University.)

URA created the ‘School of Letters’, modelled on an American University’s eponymous institution, with the objective of offering an integrated course of study with research potential, in English, Malayalam, Theatre Studies and Film Studies, to begin with, for practising and aspiring writers and translators, outside the ambit of the academic structure, but within a university’s ambience. Combining serving teachers on the Faculty Improvement Programmes, he envisaged a mixing of the academics and the creative writers under one roof, in a compact course, sharing the same classroom.

The school began with an M. Phil Course in which the English and Malayalam students sat together for lectures on subjects like Indian Aesthetics, Western Literary Theory, Modern European Literature, Theatre Studies, Literary Translation, and such. The exam was common for all. The Malayalam M.Phil students could write their exams and their dissertations in Malayalam and get their M.Phil(Malayalam) degrees. Likewise M. Phil English students could write their exams their dissertations in English, and get their M.Phil(English) certificates. The pioneering modern theatre personality of Kerala, the renowned Professor G.Sankara Pillai, was the first Director. However, he passed away suddenly on 1st January 1989. Eventually the outstanding theatre-practitioner and literary critic of the day, R.Narendra Prasad was appointed as Director before we wrote our entrance tests in late 1989; we joined for the course in early 1990. As there was a court case going on, blocking the appointment of the new faculty members except for a couple of teachers, Harris, who was teaching in Feroke College and was on the rank list, was engaged as a faculty member on a working arrangement basis in early 1990 to take classes for us.

I was at that time on service in Kerala Tourism Development Corporation, in its Unit at Aranyanivas, Thekkady, Periyar Tiger Reserve in the Idukki district. I had already completed 15 years of service. I was also into poetry writing, literary translation, trekking in the wild, fishing in the Periyar reservoir, and was always absorbed in nature in its various moods at the paradise-like settings I was in. I had brought out my first poetry collection in 1989. Leaving all that behind and sitting in a classroom as a student had been a major role-reversal for me, which I had welcomed and yet, at the same time, felt that it was something that left me bewildered—having had to sit together with students who were a generation removed from me! Working in a government set up had given me all kinds of inhibitions.

The days preceding my joining the School of Letters after being selected for the course were dreamlike. Having learnt that I translated poetry and stories from Malayalam to English, the Director, Professor R. Narendra Prasad invited me to engage in a translation project along with Harris and himself. It was to prepare a Malayalam Literature Reader at the instance of Professor John Oliver Perry, a writer in residence at the university and his wife Susan, Sue for short. I translated a few poems of Kadammanitta Ramakrishnan, and a bunch of stories by writers like Paul Zacharia; Harris did some stories, and Prasad did a play. And we were supposed to sit together, discuss, and finalise the manuscript. Prasad called this process, ‘triangulation’ which would finally lead to strangulation of the project! In the ‘high’ evenings in the University Guest House, with Prasad holding court with Professor N.N. Moosathu, Harris and I in attendance, the process dragged on. One of the major outcomes of this session was that the three of us — Prasad Harris and I – became very close.

Harris became our constant companion first and teacher next, in the dream-campus of ‘Hassan Manzil’. We were twelve scholars, including a number of youngsters–three girls, two boys and a 39-year-old ‘boy’(that’s me) who were direct students, while the other six were teachers on deputation from colleges, on ‘Faculty Improvement Programme.’ The three girls were Rajeswari Menon (also called Parvathy), Muse Mary George and Reena V.V., while the two boys were B. Unnikrishnan and A. Anvar Ali. (Anvar Ali and Muse Mary George are now noted poets writing in Malayalam, while Unnikrishnan is a film director, and a national-level leader of an association of film directors. Parvathy and Unni were married soon after the course was over.)

Harris shook us up at the very beginning. He introduced Ferdinand De Saussure’s basic principles of structuralism— ‘signified’, ‘signifier’, ‘decentering’, ‘floating signifiers’ and the rest. Decentering caught our imagination…knocking out the authority of the centre, permitting the free flow of signifiers. He then introduced us to the Frankfurt School, Roland Barthes, Claude Levi-Strauss, Michel Foucault, Jacques Lacan, Jacques Derrida, Julia Kristeva, Harold Bloom, Gayatri Chakravarty Spivak and others. Establishing ‘equality’ or ‘egalitarianism’ was his dream.

A little later, P.Balachandran, theatre-activist, playwright, director and actor, joined the School. He won us over with his instant wit, mimicry and miming and acting demonstrations of the navarasas, and scintillating classes on Bharata’s Natyasastra. He was already a friend of Anvar and Prasad Sir and merged into our company including Harris Sir.

Soon Harris and I started to compare translations together and grew even closer. He shared with me the experiences of his research days with Professor Ayyappa Paniker as his supervising teacher in the Institute of English, Kerala University, Thiruvananthapuram. Paniker had returned from Indiana University, U.S.A. with a thorough knowledge of modern western literary theory. Harris had been well-versed in it from his Feroke College days, and intended to apply it in his thesis, but was shy to be upfront about it with Paniker Sir who was a very strict guide. So, Harris went on submitting conventional progress reports on the chapters he was writing. But when the whole manuscript was complete, he went to Paniker and told him he had used ‘theory’ in his thesis. Paniker didn’t utter a word in reply, but just turned the pages, and finally okayed the manuscript!

Another anecdote he narrated was about his interview for the post of Assistant Professor in the School of Letters, with Professor U R Ananthamurthy, a self-proclaimed Leavisite asking him a question about Othello’s imperative sentence to himself: “Put out the Light! Then put out the light,” (Othello telling himself to first put out the lamp, before throttling Desdemona to death.) When URA insisted that the figurative use of the second ‘put out the light’ was much more emphatic than any ‘différance’ Jacques Derrida may derive through his deconstruction, Harris Sir went on refuting it. The argument went on for more than an hour during the interview, with Harris Sir not capitulating, and URA selected him for his sticking to his point and to his conviction!

That was the time when our course took off in full swing, with Harris holding demonstrations in deconstruction using my original poems in English and his short stories in Malayalam. Later we would hold a narrated analysis of it all with Balettan (P.Balachandran) and our classmates, in the teashop opposite the campus.

About this time I began to experience a protracted period of anxiety, owing possibly to my reversal of roles and because of the stress produced by sheer physical fatigue of travelling up and down 120 kilometres from Thekkady to Kottayam and back to Thekkady four days later—two trips a week traversing ghat roads, climbing to 1500metres braving the frequent change of weather, from rainy, to cold, misty and chilly, interspersed with hot, sunny and sultry days, for more than six months by then, and the sleep-deprived nights. Prasad Sir jokingly said that it was the pain caused by my brain shedding its rusting, but on a more serious note, he the ever-caring mento, advised Anvar to keep an eye on me so that any worsening of my moods would not go unnoticed by him. But it was Harris Sir who dealt with my anxieties, like an expert counsellor, friend and brother. About this time, a daughter was born to Prema and I, after a wait of five and a half years. The three of us would visit Harris over the next one and a half years, in his office or at his residence near the Collectorate whenever we visited Kottayam. He would call our daughter Aparna, ‘Apu,’ fondly.

When I visited him alone our evenings would end up with beer mugs in our hands. Though I was used to hard liquor for many years by then, Harris would only drink beer. That was also the time when he was finalizing the manuscript of Sandal Trees and Other Stories, his translation of the selected Malayalam short stories of Madhavikkutty (Kamala Das). It was the first practical experience for me in preparing a book of translated short stories, which stood me in good stead for my future projects.

(A decade later, he had gotten into the habit seriously as I learnt. That was the beginning of a period that would fill all of us, his dearest students, friends and admirers, a nagging worry.)

After I came away to Delhi in 1997, too, I continued my Ph. D under him and soon the time to submit the thesis arrived. He was scheduled to leave for Germany for a visiting professorship in Trier University in two weeks’ time. I had been sending him chapters of my thesis. We needed to collate them and finalise the thesis and submit it with his signature before he left. I lived in his house at Pattithanam for over ten days, working on the thesis, he joining my efforts examining the portions I had finalized, and the evenings made feisty by Kuriachan, a computer nerd, Anila’s friends from the local Women’s Collective, with Philip, the neighbour and Harris’ Man Friday chipping in with the offerings for the fiesta. This would have been a one in a billion supervisor-scholar relationship, I am proud to say!

Harris and Anila were our family friends, and when they came to Delhi, we met them. When we went to Kerala, we would visit them without fail. One occasion stands out in my memory. Earlier that day, Vinayachandran Sir had been given a farewell from the School following his superannuation. A celebration was in progress at Harris’ house when we arrived. Vinayachandran’s wailing tempest-like poetry recital, followed by Balachandran Sir’s mosquito dance, and mono-act thrilled Aparna. But what thrilled her most was Harris’ ghazal-singing in his ever-soft, melancholy voice! He had sung at Aparna’s request.

![]()

Harris with poet P. Balachandran

The literary translation camps we attended together, at Kottayam, Hampi, KILA- Thrissur and in Ernakulam in 2011, my visit to the venue of the shooting of his film on Vaikom Muhammad Basheer using the still photographs by Razak Kottakkal, and which his student of Feroke college Jamal produced, and many more of our rendezvous and times spent in each other’s company have left in me living memories which I find hard to handle, now that he is gone.

*

What set Harris apart from the other teachers was his egalitarian vision. He practiced what he preached. He was never the central-authority-wielding pedagogue; he was always with the students, always available at their level.

The concept of Decentering which he practiced consisted in not assigning a central meaning of importance or relevance to one particular text or person or institution. One incident is still vivid in my memory. After our course was over in 1991, Anvar, Harris and I got together many times. I remember one rainy afternoon in Andrew Xavier’s Annexe behind the Secretariat, Thiruvananthapuram, sometime in the mid 1990s. We had been talking about decentering and deconstruction; Anvar asserted that Ezhuttachan or Kunchan Nambiar were beyond analysis based on such western tools. The next moment we witnessed an unforgettable expression on Harris’ sage-like face: utter disregard for a text with fixed meanings, explaining that the entire universe is a text, and we produce meanings of each component through the ‘différance’ derived from their inter-relations.

The main topic of discussions nearly four-five hours long was Ezhuttachan’s works, particularly about Adhyatma Ramayanam, which D Vinayachandran had been urging his poetic wards to read at least once, to trigger the poetic voice inherent in one’s self.

Harris disagreed. He made his position clear…that Ezhuttachan’s work was a text just as any other, and one needed to look into how meaning is generated in it, the play of signifiers and the whole gamut of modern theory. Anvar strongly disagreed…the exchanges went on for hours, but finally we parted, sobered with the realisation that any overriding narrative was against the sense of justice towards other narratives which are less known, or popular…that every text had its place in the general scheme of things, and it was not necessary to espouse one single text for all eternity…their relevance as played out by the spatiotemporal demands, needs or necessities would determine their relevance…the forces of history as it rolled on…

Everything is far from being infallible: that was his credo. For him, everything was open to problematisation and scrutiny. He urged others not to have de facto heroes or idols…

Everyone has equal rights in a democracy. The key concept of Equality, the primary slogan of the French Revolution, “Liberty, Equality and Fraternity” was the guiding principle of egalitarianism…

![]()

Courtesy: Ambily Dileep

As a teacher, he never assumed superiority over his students as I mentioned earlier—he opened out his affection to all…it was upto the students to accept it or not in the right spirit.

He would never relinquish his duties as a leader, inherent in his vocation of a teacher though….Many good friends of mine who are teachers, editors, poets, actors and writers now, would remember the various ways in which Harris made them follow the straight and narrow path of pursuing one’s true vocation….I have already related my own experience…how he literally became a friend, philosopher and guide to me…I am sure there are several hundred more students and research scholars like me who have drunk from the fountain of his affection and care ..

His social activism was practised by moving into the peripheries—for example, working hard to bring justice to the victims of gang-rape, with the active assistance of his partner Advocate Anila George; giving unstinted support to dalit activists, in theoretical, practical, and material spheres; working for the protection of environment through support for the awareness programmes of NGOs and also by acting in the main character role in a national-award-winning film with an ecology-oriented subject, titled Jalamarmaram. He always stood with the employees of the University to find just solutions to their genuine grievances. His academic and intellectual achievements and his simple and plain living were exemplary.

One literary critic even remarked that a senior professor and the Director of School of Letters meeting with an accident while travelling in an auto rickshaw that claimed his life, would be quite unbelievable to many, as most professors of his rank would be travelling in an air-conditioned car!

His relationship with films is worthy of special mention. Having been actively associated with Odessa Film Society, and particularly the Malayalam avant garde master John Abraham’s classics, it was only natural that he would apply his keen intellect to film studies. Having himself acted, scripted, and assisted in the making of a few films, he had taken up teaching Film Studies in Trier University, Germany in 2002 for more than a year.

He mingled with the highest academicians, politicians, writers and artists, and also with autorickshaw drivers, attenders, daily wagers and such very ordinary people, in a true sense of egalitarianism. He was merely enjoying the great drama of his life, giving everyone equal importance and a place in his own existence…Those who did not understand this were blinded by their own self-importance. Harris was like a renunciate—like a jain muni, Christian saint, buddhabhikshu, Hindu sanyasi or a Sufi saint… only that he didn’t deny himself food and drink and the legitimate pleasures of life….

He never hankered after worldly possessions and status…a senior University professor travelling in an autorickshaw was scandalous for many of my writer friends in Delhi, like the literary critic who wrote in one of the obituaries…he cared only for humans…By being egalitarian, he always kept fear out of his personality. He would budge to none, and he never wanted anyone to budge to him.

Fear is born when one harms or defeats the other, and fears being harmed or defeated in return. It is fear that creates gods, bullies, dictators and exploiters. It is fear that creates the need for possessing and accumulating things. In the final analysis it is fear that brings about the evils of capitalism, oppression of women and differently gendered individuals, and degradation of environment which began with wanton killing of wild animals and felling forests which had made nature inscrutable!

Harris ‘Sir’ was free from this fear. This sense of freedom gave his persona a glitter, a gleam, a lightness of being. Anyone who has witnessed him singing a ghazal, his eyes closed in total absorption, would understand what I am trying to say.

2

![]()

S. Joseph

Dearest Harris, for you…

Harris! Burial over

everyone has left.

Three days it rained,

the plot, now hosts thick green grass.

Me and my family,

from our balcony, your grave

we see.

Once, when scalding prices

made the dream of owning land

a mirage, me and my family roamed,

landless – for eons.

At that time, you

took me to a place

that literally was a forest.

The title-deed of that place –

to the snake, the crane and the owl belong.

And how many lanes you and I traversed,

so that you and I too would get a title-deed!

At long last, on our very land,

we built a house.

And were you roaming

with the picture of a mud-house?

Was it torn up into tiny pieces and

given, to the wind, to be blown away?

You, one who resided

with your name absent from all religions.

You, one who carried intoxication along,

just like a Sufi.

You, the Scop who,

when tipsy, would untie the knots of stories.

You, the traveler, whom no host will

ever get to meet at the main pathway.

You, who left this little-and-large world,

after a mere caress-touch.

Through gesture, more through talk,

you wrote and erased and then just vanished.

In the plot you bought,

your grave stands.

The sun tans it.

The rain wets it.

In its sky, a crowd

of crows explode.

There, snakes mate

as though writing with fire on air.

In the second measure of the deep night,

the owl’s hoot echoes there.

And at the end of that hoot,

our sleep-catacomb.

From our balcony we see you,

me and my family.

There is a smile on our faces,

from that smile scatters

water-drops, all around.

Attachment:

Song of the One Who Went in Search of Earth

Towards the South-est, South-ey horizon

I went in search of land.

And while coming back with no-no land,

on the way a song I heard.

The song, I knew,

was Saigal- sung.

I just walked

till the song’s very end.

There, a person,

bearded, curly-haired, ever-smiling.

I stayed put there

with story and song and intoxication.

That day was his day-of-birth,

and I sang a verse too.

Some one placed a crown

of Jak tree leaves upon his head,

and he accepted it all,

with a ready smile, just like that.

And time flew

amidst such banter and games.

That day, as I took leave from there,

my woes and woes just vanished…away.

In that horizon, on one day,

he pointed to me a place, just there.

There, today, under

a Kanjiram tree, my home.

Further, down, there stands

a Kudampuli tree.

Beneath it sleeps

the silence of a song.

Like in the times, when many

gathered around that song,

even today a gathering remains –

of birds and small creatures.

There, in the rain,

dragon flies dance and play.

From there, I embark,

every morning, me…

[Translated from Malayalam by Cheri Jacob K.]

3

![]()

Cheri Jacob K.

By(e) and Because: A Harrisian Re-members….

When fathers depart, sons attain adulthood and grow olden. Harris is gone. I feel olden – as about adulthood, me can’t be sure…

A Translator’s Organum – Now, let me share this. The(se) event(s) of translation is, for me, an act of mourning – an engagement that tries to wrest the subjective-emotional away from the objective-historical. And yet, the involvement is entrenched in the acutely personal and it overwhelms – I hear/embrace emblematic echoes, of Roland Barthes remembering his mother [in his Mourning Dairy] and Jacques Derrida stifling his sobs to come to terms primarily with the absences of Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault and Paul de Man [in his The Work of Mourning]. The absence-presence conundrum and the afterlife of the survivor-mourner…

As about the very act of translation, just a word about the process, especially the Titles: S. Joseph’s, Mine. I have somehow ended up avoiding ‘exactitude.’ And for this I have made use of diacritics, punctuations and parentheses as strategically essential translation tools. That leads to the issue of translation-morality: fidelity, equivalence, semantic balance and the like. However, it is the feel and the tenor that counts, I ardently feel. Somewhat a corollary to the common-parlance-sense that a ‘rose would smell just as sweet’ even if called by another name!

And I dare to veer away from ‘good taste’ into the realm of what Roland Barthes designates as ‘bad taste’, primarily because I have been mentored by a wonderfully perceptive translator who took the likes of Basheer, V. K. N., Maythil and Kamala Das to creative heights via the route of ingenuous (un)broken rules – Harris, the Immor(t)al Translator!

Let me also put on record that my love for Translation Studies – both its theory and praxis – has a lot to do with Harris’ stint as editor at MLS [under MT’s stewardship], especially the special issues on Literature and Film, Women Writing in Kerala, Malayalam Dalit Writings, etc. Those are issues which I still hold on to as the cornerstones of my translation consciousness…

Let me leave you with a translation insight that Harris formulated: ‘Translation is akin to dreaming up a vision of Narayani [the ‘invisible female protagonist of Vaikom Muhammad Baheer’s novel Mathilukal (Walls)], from just her voice – a voice that falls on human ears/souls from beyond The Walls.’ – Basheer’s Translation Treatise! And now, it seems to me, that Harris is demanding a similar translation. But, the lingering voice is all that is left – that too like a candle in the wind, deep in the recesses of the hearts of all those who hold him so very close. Can I/We translate? Well, maybe I/We have to, once again, take refuge in Derrida: ‘I’m Going to Have to Wander All Alone’ [a chapter title in his The Work of Mourning]. See You, Harris…

*******

Also read Rain-Clouds and the Darkish Smile: Short Fiction by V. C. Harris

A.J. Thomas is an Advisor to The Beacon. He is a poet, translator and was till recently editor with Indian Literature.

Cheri Jacob K is a film/literary critic and translator. He teaches English at Union Christian College Aluva, Kerala.

S. Joseph(born 1965) is a Malayalam poet with six poetry collections and other writings to his credit. Translations of his poetry have appeared in India Poetry International web site, Poem Hunter. Penguin Books published four of his poems in a collection No Alphabet In Sight. The Oxford India Anthology of Malayalam Dalit Writing included two of his verses. In 2012 he received the Kerala Sahitya Akademi Award and in 2015 Odukuzhal and recognition/acclaim for individual poetry collections. S. Joseph has been translated into several European and Indian regional languages. "

A.J. Thomas in The Beacon

Cheri Jacob K in The Beacon

Leave a Reply