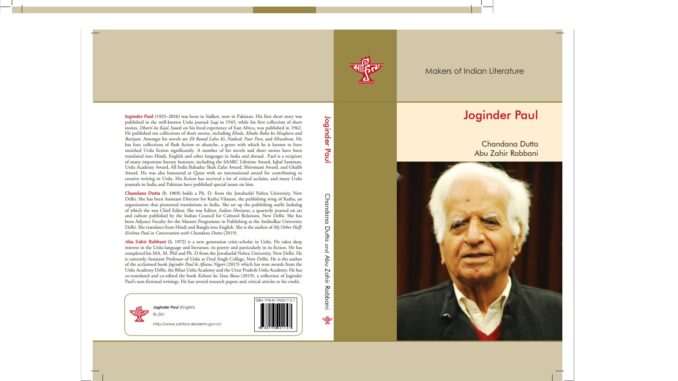

Joginder Paul (Monograph/MAKERS OF INDIAN LITERATURE SERIES)

By Chandana Dutta and Abu Zahir Rabbani

Published by Sahitya Akademi

Ranjana Kaul

J

oginder Paul is a critically acclaimed writer whose name is familiar to every afficianado of Urdu literature. His extensive body of published works, many of which have been translated into other languages, include novels, critical essays, short stories and flash fiction or afsanche. This was a genre which he made very much his own, publishing four collections of these brief literary works, experimenting with and mastering the art of conveying powerful ideas and themes using a bare minimum of words.

The variety and complexity of the body of work which is the legacy of Joginder Paul and an intimate look at the man and his work through the eyes of his wife and soulmate, Krishna Paul, are the subject matter of the two books under review. The first is a monograph on the writer authored by Chandana Dutta and Abu Zahir Rabbani which is a part of the series Makers of Indian Literature published by the Sahitya Akademi. It provides an analytical, detailed, and informative look at the author’s works and the themes and varied literary concerns that animated Paul’s fiction. The second book, My Other Half, is a narrative based on a series of conversations between Chandana Dutta and Joginder Paul’s wife Krishna.

Born in Sialkot, Pakistan, in 1925, Paul moved to Ambala after the partition and then to Kenya, Aurangabad, and finally to Delhi, a peripatetic existence which inevitably gave him a deep insight and sensitivity to feelings of displacement and exile. As a young writer, he joined the Progressive Writers Movement which was launched in 1935 with the idea of propagating a literature that would reflect the socio-economic truths of its time as well as their impact upon the lives of individuals. However, he ultimately came to the conclusion that a writer should constantly continue to experiment with new thoughts, ideas and genres and “should never restrict himself to any ideology or group if that meant surrendering his freedom to write as he pleased.”

Chandana Dutta and Abu Zahir Rabbani’s monograph provides an excellent introduction to the intellectual strength, experimentation, and engagement with the use of language, both of which are such an integral part of Paul’s work. Devoting separate sections to a detailed critical analysis of his oeuvre, the writers point out that, “even today his stories and ideas are as refreshingly apt and powerful, as relevant in their topicality and outlook as they were in their own times,” not merely because of Paul’s “imaginative thought and expression,” but also because he was so modern and of his times, “perhaps even ahead of his times.”

Dharti ka Kaal, Paul’s very first collection of short stories, published in 1961 was based on his experiences of life in the African subcontinent, where he spent a considerable amount of time. It was a place he went back to, for inspiration, in his novel Nadeed (Blind) many years later. The subject and style of Joginder Paul’s writing was very passionate, varied and modern. While dealing with emotive themes such as the Partition and confronting social issues, he also moved beyond them to a world of dream, fantasy, nostalgia and magical fiction in works such as Beyond Black Waters and Sleepwalkers. Using nostalgia and memory as means of questioning and reexamining concepts such as displacement and belonging, he ruminates on the manner in which people who are uprooted sometimes fashion an alternate reality which provides comfort by recreating the space they have been forced to leave behind. Deewane Maulvi sahib, the main protagonist in Sleepwalkers, a mohajir, recreates the beloved Lucknow of his memory in Karachi and exists within this illusory bubble. When this fragile reality is inevitably shattered, and he is forced to accept the fact that he is in Karachi, he waits in anticipation of repatriation to Lucknow!

The complexity of the narrative creates a context within which the writer focuses on the tragedy of being uprooted by engaging with protagonists who occupy a liminal space, at least in their minds and hearts, which belongs neither to India nor to Pakistan. As a Partition writer Paul examines the relationship between selfhood and domicile, of how the reality of belonging to a physical space becomes an integral part of an individual’s identity. Inevitably, exile is a subterranean theme that runs through and enriches a lot of his work.

**

![]()

My Other Half

Krishna Paul (Conversations with Chandana Dutta)

Published by Red River November 2019

While the monograph provides a detailed and informative look at the works, themes and varied literary concerns animating Paul’s fiction, it is Chandana Dutta’s narrative recreation of conversations with Krishna Paul, My Other Half, which goes beyond a normative engagement with the writer’s oeuvre to provide an unexpectedly intimate and engaging glimpse into his life and work. It is written from the unique point of view of someone who shared the writer’s life, as a supportive but critically aware individual who did not always agree with the author’s literary and life choices.

Born in Kenya and married to the author in 1948, Krishna Paul retained her own separate identity, working as a broadcaster, lecturer, and translator apart from pursuing her interests in culture and theatre. Dutta confesses that during her interactions with Krishna Paul the focus of her attention shifted from the author to “this woman behind the storyteller. Who was she really? …. My conversations became as much about Krishna Paul as about her husband.” And the book took on the form of a narrative as, during the course of the conversations, Dutta realized that, “she was narrating a captivating story and the best way to convey that would be to keep the essence of the story.”

Written in a lucid and engaging style, the narrative in a sense becomes an intimate biography of the author, who never really got down to penning his own memoirs, as seen from the point of view of someone who knew him best. Beginning with the consternation caused by Paul’s insistence on spending time alone with his newly married bride in the Ambala railway station waiting room, the narrative, written in the third person, interweaves the personal and the literary, moving seamlessly between personal anecdotes and experiences, connecting them with nuggets of information about the genesis of various literary works. Referring to the very first story narrated to her by her husband, “Byahta,” Krishna Paul wonders if the story was chosen deliberately to “convey to her, subtly, his deepest desires of what a marriage should mean, or even how a married woman should behave.”

The book offers a glimpse into the soul of a restless, driven man for whom his writing was the raison d’ etre of his existence, a complex individual who managed to combine an innate compassion and sensitivity towards other human beings with an obstinacy which uprooted his family time and again just when they had achieved a modicum of comfort. As an “Imported husband”, he moved to Kenya after his marriage, to his wife’s home and to a life which was more stable and rewarding in financial terms, but he remained a perpetual outsider who was quite dismissive of this bourgeois society to which he never really wanted to belong. After a fourteen-year sojourn in Kenya he willingly gave up the respect and financial stability he had achieved during his stay in Nairobi to move back to India and pursue his love of writing and of Urdu.

With an honesty, of which her husband would surely have approved, Krishna does not gloss over his quirks of character. She draws attention to the apparent contradiction between his basically compassionate, generous, and humane nature and his ability to hurt people through his bluntness. However, while accepting these contradictions and moulding herself to fit in with his expectations of her being a typical housewife, she nevertheless retains her individuality and critical ability, and this is what makes this slim and attractive volume so interesting and insightful.

The narrative is interspersed with nuggets of information about the writer and about real-life situations which become the basis for stories, revealing the manner in which the creative process reworks and reinterprets an incident or an event. “Kamina,” for instance, was based on their experience of selling their car while leaving Nairobi though Krishna Paul strongly felt that the incident and her words were “coded in his writings in ways different from her understanding of the situation, of how she remembers it.” A visit to Lake Kikuyu and a chance remark by an old African later metamorphosed into another story “Mojaza.” As Krishnaji tells Dutta, “A tiny spark like this could shape into a brilliant piece in Joginder Paul’s hands. He would be quiet for days. He would be restless, something or the other roiling in his mind … For months together he cogitated and created. It was a process that caused him great pain and suffering. Each piece he wrote was an experience; he lived and felt what his characters did.”

He would discuss the stories, once complete, with his wife and she became his sounding board to the extent to which a writer will allow another individual to impact his or her creations. She rightly says, “I have not travelled any less with him in his literary journey.” While revealing the man behind the author and the woman behind both, Dutta’s narrative reveals the deep bond that grew between these two wholly disparate individuals and Krishnaji’s growing understanding of the compulsions that drove her husband to write. In the brief article, “Only I Would Know” written by her which has been translated from Hindi and which appears at the end of the text Krishna Paul astutely remarks, “His stories and his life are no longer two separate things. Stories are Paul’s life and his life is a story.” She realizes that the apparent disorder of the man and his stories is a “‘crafted disorder’ which is held together with a consciously crafted sense of order, both in him and the stories.” This is an insight which comes after spending half a century with the writer and while there is a sense of pride in the fact that she was Joginder Paul’s first reader there is also a sense of wistfulness in the acknowledgement that, “I have still not understood how far Paul understood me in return.” A wistfulness set off by the wry recognition that “… perhaps that wouldn’t be so easy either.”

This refreshing book is significant not merely because of the unusual viewpoint from which it regards Paul’s work and life or because of its honesty and plain speaking but also because it reveals another individual whose journey becomes as interesting as the literary journey of the author himself. Krishna is aware that her husband, the storyteller, has turned her real life into a story as well but she has no regrets because “The wife of a storyteller must perforce become a story herself …” This brief narrative provides the reader with an opportunity to get a glimpse into her story and into mind of this “friend and partner, first auditor and muse, keeper of all of Joginder Paul’s memories ….”

Together these two slim volumes provide a nuanced, critical and multi-faceted introduction to the life and work of an outstanding writer whose works have enriched Urdu literature and helped greatly to popularize the language.

********

Chandana Dutta is an author, editor and translator. She holds a Ph. D. from Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. She has been Assistant Director for Katha Vilasam, the publishing wing of Katha, an organization that pioneered translations in India. She set up the publishing outfit Indialog of which she was Chief Editor. She was Editor, Indian Horizons, a quarterly journal on art and culture published by the Indian Council for Cultural Relations, New Delhi. She has been Adjunct Faculty for the Masters Programme in Publishing at the Ambedkar University Delhi. She translates from Hindi and Bangla into English.

Abu Zahir Rabbani is a new generation critic-scholar in Urdu. He takes deep interest in the Urdu language and literature, its poetry and particularly in its fiction. He has completed his MA, M. Phil and Ph. D from the Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. He is currently Assistant Professor of Urdu at Dyal Singh College, New Delhi. He is the author of Joginder Paul ki Afsana Nigari (2015) a book that has won awards from the Urdu Academy Delhi, the Bihar Urdu Academy and the Uttar Pradesh Urdu Academy. He has co-translated and co-edited the book Kahani ka Tana Bana, a collection of Joginder Paul’s non-fictional writings (Vani Prakashan 2021).. He has several research papers and critical articles to his credit.

Ranjana Kaul was Associate Prof., Dept. of English at College of Vocational Studies, University of Delhi. Her areas of interest are cultural and imaginative narratives of migrant and displaced peoples and the impact of socio-political determinants on literary representations of women especially those belonging to minority communities. She translates extensively from Kashmiri and Hindi into English. Her translations include This Metropolis by Hari Kishen Kaul (Sahitya Akademi 2011)), Paper Bastions by Meera Kant (Rupa Publications 2011) and Saga of Satisar by Chandrakanta (Zubaan Books 2018). She has also translated numerous short stories for various journals. Joginder Paul in The Beacon

Leave a Reply