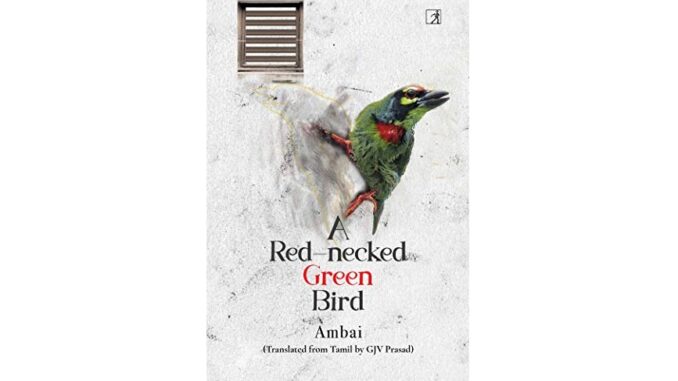

A Red-necked Green Bird. Ambai Translated from Tamil by G JV Prasad. Simon & Schuster India, New Delhi. March 2021. 201 pages

Pradeep Trikha

‘A Baker’s Dozen’

C

ontemporariness, transitory human emotions, and sexuality are the ingredients of Ambai’s A Red-necked Green Bird. The collection has a thirteenth banana in a dozen. Ambai (pen name of C.S. Lakshmi) conjoins metaphors, images, and allegories in stories, mainly drawn from women’s lives. The Tamil author, now living in Mumbai, stays close to home sometimes visiting megacities like Delhi. Her primary concern is to look closely and deeply into the lives of Tamil immigrants in these cities. Ambai uses a vast canvas to express their anxieties and fretfulness regarding human relationships, their personal and domestic experiences, tender and poignant emotions, for example in ‘The Crow with a Swollen Throat’, ‘The City that Rises from Ashes’, ‘A Red-necked Green Bird’, ‘Two Empty Chairs’ and ‘The Lion’s Tail’. Like their histories, ‘food’ also connects the family. For the readers with epicurean interests of their own Ambai deliberately adds cuisine as a narrative device. It is a delight, as in “The Crow with a Swollen Throat”

“Food, I want food… Appa screams when she

entered his room; his nurse was trying to pacify him. You ate just now, didn’t you,

Appa? Didn’t I give you rice, rasam, appalam, everything?’ Her father saw her entering and shouted, ‘Food…’

She sat next to him, ‘Appa, have you forgotten? Today there was pepper rasam and cluster beans poriyal with coconut the way you like it. And rice appalam…’ (3)

Beyond the pleasure in gastronomic details, food in this collection does much heavy lifting, signalling home and connection. At moments of emotional intensity characters head to the kitchen either cooking something, making tea or coffee or chalking out a menu for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.The culinary comforts enhance the relish that the reader feels in the baker’s dozen (that is, 13) stories, the extra delight standing for the thirteenth piece.

Ambai’s stories are multi-dimensional, addressing issues related to society, politics, religion, Partition of 1947, Sikh carnage of 1984, the impact of globalization; all that leads to an existential crisis in the lives of men and women. The writer shows the impact of globalization in ‘The City that Rises from Ashes’. Rapid growth in the real estate business in the megacities brings about a drastic change in the lives of its people; Ambai shows how the marginalised sections in the society were further been marginalized during the process of ‘growth’ and ‘development’. A parallel in the story is drawn from the myth of Khandavprastha in Mahabharata:

“…it was after Khandavprastha was razed in a fire that Indraprastha came up. The home of Nagas, the tribal people one which housed various birds and animals, it was turned into ashes … A Takshak had escaped the fire caused by Indraprastha to take revenge” (22-23).

Globalization, as the story underlines, has benefitted only the big players and not the last man in society.

The title story of the collection, ‘A Red-necked Green Bird’, ferrets out human skirmishes and ensuing identity crises. The story revolves around a father’s dilemma over his adopted daughter Thenmozi’s speech and hearing disability. Initially, Vasanthan (the father) does not accept the reality and desperately saves money to rectify the disability, clinically. The story attempts to sensitize those who chase the “mirage” of ‘the whole’ and ‘the normal’, pointlessly. The story concludes thus:

“That you can reach others with colours and without sound is best exemplified in India by Satish Gujral; he lost his hearing at ten and conversed only by reading lips. He couldn’t hear his voice. The sound that he heard after the cochlear surgical procedure he underwent when he was seventy-two was an electronic one processed by a computer chip implanted in his brain. He often felt that sound was an assault. In his seventy-eighth year, he had another operation to remove the implant. He painted a series with a memory of sound and the safety of silence and exhibited them under the title ‘Back to Silence’. These paintings that have overlapping images are reckoned to be his best paintings. Language is communication. It can happen without sound.” (83)

The story commences with the present, delves into the past of the characters’ lives, and completes the circle by returning, in the end, to the present. Vasanthan leaves the house and his family, writing a note that declares: “I can’t stand anything. I don’t need to. I am a freeman. I hate all bounds. You know it. So, I am going”. (41) Initially both Thenmozhi and her mother Mythili feel that he would return in a day or two. As time goes by, they realise that they should search for him. After leading an active life in the advertising world, he had taken a sort of retirement and had devoted himself to looking after his daughter and wife. He started taking keen interest in household chores. It was he who ‘decided the menu from morning breakfast to the special meals on festivals’ (59).

The story is rich in metaphors, images, symbols and literary allusions. Thenmozhi’s news report submitted at her school read thus:

“In the world that I, we -Edwin and I- live in, there is no sound. Drops of sound fall on us through our hearing aids. They are hot. Hot as fire. Sound is a whip. Gives pain. That is our relationship with sound. There are colours in our world. Visuals too. Earth red. Blood red. Maroon. Vermillion red. Parrot green. Moss green. The green of tender sprouts. That blue. Sky. Light blue. Dark blue. The blue that has both the colours mixed. If you enter it you have paintings from Monet’s blue period. With a river mixed with the sun’s red. If you go swimming in it you reach Van Gogh’s painting of a bedroom blue walls. With blue shirts hanging. Shut blue doors. A table holding a blue bowl, a blue glass pitcher and few blue glass bottles. A painting with blue in it at the head of the bed. Yellow, red and light green are the bed and the bed cover and the chairs. The shut windows have the brush strokes of green.

…Sound is aggression. One that fells silence.

Silence is an ocean. An ocean with buried secrets…We are enjoined to them”. (65-66)

The passage delineates the agony and stress of a school going child who confronts the adult world that considers disability a curse and burden.

A Red-necked Green Bird is a site where the relationship between narrative form and the construction and reception of cultural identity can be questioned. “Two Empty Chairs” deals with appropriations, denials and subversion of myths. It even blurs distinctions between fiction, myth and history. Ambai operates with transnational concerns and challenges historical ways of thinking. This approach is to be welcomed because it goads us on to rethink myth, history and its complicity in power.

It’s a story of an Indian, a Turkish, a German, and a generational gap. Luisa, adopted daughter of Nikhil Bhattacharya, recounts her mother Emilia’s love affair with her biological father from Turkey. Luisa comes to live with her stepfather Nikhil. She recalls her younger days when she used to accompany her mother to Ramayanam discourses. She notices an extra sitting plank on the stage and is intrigued; her mother informs her about a common belief in India that wherever the Ramayanam discourse is organized, Hanuman would come to listen. Luisa relates it to her own life by arranging two unoccupied chairs in the first row whenever her father organizes a musical concert. The story opens with Nikhil’s muddled thoughts, when he receives an email from Luisa announcing her arrival to Mumbai to stay with him. He is reminded of Emilia, her mother. He is perplexed:

“Nikhil was always doubtful as to whether she was a friend or enemy. She was both, he would say. She was the one who criticised him the most. She was also the one who tried to bring him out of the substance addiction, and away from the grip of alcohol. Nikhil was someone who had fully immersed himself in the hippie culture that began to spread in Mumbai in the seventies. Its objective was to question all that was holy, all authority, he said”. (176-177)

Ambai leaves room for the reader’s interpretation. Unfortunately, she gives in to the impulse to over-explain. “The Lion’s Tail” is a story of a working woman who lives on her own:

“She was an ordinary girl. That is how they raised her. Her broadminded, educated, working parents. They had studied abroad and then made Mumbai their home” (142).

Madhura, the protagonist of the story works in the field of computer applications, confronts an unusual experience which she believes is from the ‘eleventh dimension’. She even writes to a scientist to understand the facts but eventually is to be taken to the psychiatric hospital for the treatment. The story concludes with, suspense and romance, “Madhura disappeared in a cloud of smoke” (175).

Almost all the stories are woman-centric and the world is seen from the woman’s point of view. Translated from Tamil by GJV Prasad, an eminent academician, poet and critic the collection offers up an interesting take on the dialogic content between the original writer and translator. . As Ambai, in the preface ‘Stories and Me’, puts it, “We arrived at a process of translation exchanging views and ideas reaching an understanding that the original story will always remain a different experience of writing and reading. Translation can touch it but it will never be an embrace. It was a pleasure working with GJV Prasad on this translation with arguments and fights which always ended in laughter after resolution.” (xi).

Needless to say, the translation for those who have little or no Tamil is indeed a boon, and Prasad’s felicity in both the languages helps reach this collection to a wider audience: thirteen stories a ‘baker’s dozen’.

******

Pradeep Trikha, is Professor in the Department of English, Mohanlal Sukhadia University, Udaipur, Rajasthan, India

Ambai is the nom de plume of CS Lakshmi whop has been an independent researcher in Women’s Studies for more than forty years. As Ambai she writes fiction in Tamil and her short story collections have been published and translated into English. She is currently the Director of SPARROW (Sound & Picture Archives for Research on Women). A Red-necked Green Bird is her seventh collection of short stories. She lives in Mumbai, India.

GJV Prasad is a Professor (retired), Centre for English Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

Leave a Reply