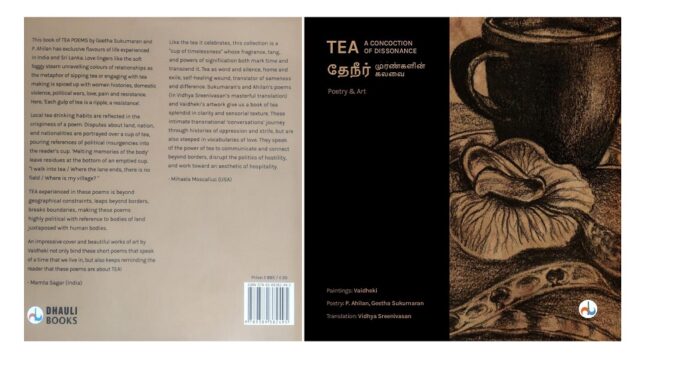

Tea: A Concoction of Dissonance. Bilingual Poetry—Tamil/English, by P. Ahilan Geetha Sukumaran (translated from Tamil by Vidhya Sreenivasan) and Paintings by Vaidheki. Dhauli Books, Bhubaneswar: 2021. 108 pages –

A.J. Thomas

R

uminations on tea, its relationship with the modern human psyche, the resonances of empire-building, colonisation, free trade, monopoly, exploitation of poverty and of inhuman exploitation bordering on mass enslavement, ethnic trafficking which ended in ethnic cleansing and genocide—all these can be read into the poems and the paintings in this volume, somewhat like the esoteric astral readings by clairvoyants using tea leaves or dregs in a teacup.

The mystic tea-ceremonies of East Asia, specifically of China that go back to about five millennia, along with those of Korea, Japan, and other countries, and of Turkey, Morocco, and certain other nations of North-West Africa, nourish already extant rich traditions. The almost-similarly arcane addiction to tea that the British acquired during the 17th century, (the Dutch having newly introduced it from China, which was where this herb was exclusively grown,) triggered a particular branch of colonial expansion and cultural sophistication in those lands conquered by the coloniser.

British aggression in China that began in the early years of the reign of Queen Victoria, known as the Opium Wars, was really intended to break the adamant Chinese who refused to give up their secrets of tea and its cultivation. (A similar anecdote involving the Portuguese conquistador Vasco da Gama and the Zamorin of Calicut in the early 16th century, involving the cultivation of the pepper vine is prevalent in Kerala. When one of the courtiers of the Zamorin informed the king that the Portuguese were clandestinely planning to grow pepper vines in their native land, having smuggled its tendrils out of the country, the Zamorin remarked wryly: ‘They can try all they want! But how will they smuggle out Tiruvaatira Njaattuvela?’ This latter phenomenon was a peculiar rain-shine combination that lasted about ten days during the Southwest Monsoon, from June 22 every year, in the specific geographic location of Kerala–longitude and latitude-wise–which could never be transferred elsewhere! Even the hapless colonies had a thing or two up their sleeves against the colonisers!!)

Having eventually learned the art of tea-planting, the British colonisers set up tea estates in India in the high range and terai areas of the Indian subcontinent like Darjeeling, Assam (and other vast swathes of tribal lands in this Province), the Nilgiris, Valparai, Munnar, Peermade, and the hilly areas of Ceylon (Sri Lanka), to ensure uninterrupted supply of the heavenly brew across all classes of their society. The habit of tea-drinking spread to the elite imperial subjects in all the colonies of the empire where the sun never set. Countless struggles driven by different ideologies were spawned by the devotees of this golden orange beverage. There are also individual cases of illustrious names, involving tea and its exquisite nurturing qualities. Karl Marx survived on green tea and biscuits in London during his early struggling years of exile! About a century later, V.K.Krishna Menon, the fiery Indian nationalist, “a stoic workaholic who thrived on endless cups of tea and biscuits…(Siddin Vadakut in Mint, 18 July 2013)” as he lived and led the struggle for India’s freedom in London in the 1930s.

In the 17th century, a Mongolian trader had introduced the herb to Tsar Mikhael I, and by the 19th century, all over the Russian empire the samovar and tea-brewing had acquired cult status(as one learns through Russian literature of the period.) In the 20th century, the Chinese overwhelmed the Arab world in the Middle East and the Magreb, and the population of the entire Levant, through their green tea revolution. In these parts of the world, a sumptuous meal is always accompanied by tiny glasses or porcelain cups of sweet, hot green tea!

Now, the two poets and the painter who put this book together have engaged in the conjuring act of artistic creation which enriches the 100-odd pages of this exquisite volume, which has been dedicated to tea plantation workers.

The loaded poetic “Foreword” by Riaz Latif, nevertheless, successfully places the book before the readers, giving a whiff of what one is to encounter in these pages. Read how he describes tea and its magical hold on people: ‘These poetic meditations spiralling in the ineffable stirrings of tea, these gnomic “concoctions of dissonance,” unfold a veritable apotheosis of the herb. The aromatic steamy mists rising up from the premium flush of freshly brewed tea drape in their wafting the unborn worlds of fiery incantations—sublime elations, scorching agonies, dewdrops of tender intimacy, the violence in our souls, the visceral hues of menstrual blood that stain our perennial apathy. Succinctly, germinating from the Samudra-manthan of tea, these poetic ruminations are like liquescent shards strewn around the unfinished torso of existence….’

Interestingly, each collaborator adds a preface about what prompted their involvement in this project and this makes for interesting reading. The painter, Vaidheki, in a short paragraph, titled “Drawing Tea” also describes how she conceived and realized the artistic vision ensconced in the book, through her works interspersed among the poems. She succinctly puts it: ‘The creative act is a journey with a stranger where the self is occupied with the self; it is an inward journey.’

Ahilan (incidentally whose poem –“Maruvili-Echo-Reverberation” translated by Geetha Sukumaran –I had the honour of publishing in Indian Literature No.315, January-February 2020, in memory of the great Malayalam poet Aattoor Ravivarma, who had been engaged poetically with the Sri Lankan Tamils’ struggle for long) has written a paragraph, “Writing Tea”, introducing his contribution to the anthology. Here he narrates the story of how this volume came about. It all began with Vaidheki’s paintings with tea-drinking and its accessories as subject matter. Ahilan had continuous conversations with Vaidheki on this topic.

“These conversations created a cultural framework within which I could talk about the socio-political dimensions, the intricate cultural and psychological folds hidden beneath this quotidian practice. Thoughts about how this everyday gesture takes shape as a language of the body, as the structure of a tradition and the way it is intricately woven into social positionalities took root in me. These thoughts opened up the world of tea for me. In the shaded venues of that world, I found my words.”

He shared these with Geetha Sukumaran, and thus, this book project involving the three of them took shape. In “Tasting Tea” Geetha Sukumaran based out of Canada shares reminiscences of her childhood when she began to acquire the tastes of different varieties of tea-preparation, and how they shaped her approach to this celestial brew. ‘Perhaps because I had spent much of my childhood in several North Indian cities, memories of varied tastes of tea brewed in different colours in my mind during my discussions with Ahilan and Vaidheki. Since Canada is a coffee country, Indian ‘chai’ is often identified with an intense hint of cinnamon….’

Transcending geographical borders, ‘tea’ took on the tint of a cup in myriad thoughts boiling together: Zen Buddhism, colonial plantation slavery, indentured labour, class and gender divisions, multinational corporates, consumerism, and human relationships. In the narrow streets and wide streets, at all times, amidst the taste of the cup of tea someone holds somewhere, a tea moment happened singularly for us. A moment that transpired into art and poetry.’

![]()

Ahilan has written 30 short poems in Tamil, ranging from 2 lines to 8 lines in length, most of them usually falling between 4 and 6 lines. The English translations are at the bottom half of the page. The thick black characters of the Tamil script and the formally chiselled black of the Roman script of the English text together make the page on glazed art paper, also a work of art.

Sample these:

Poem No.1

I am no one.

The morning tea that you have*,

sitting on the verandah

after the rains that poured last night.

If the original Tamil word ‘arunthum’(drinking—’you are drinking,’ in this context) instead of ‘have’ was used, the translation would have been more to the point.

Here is the picture of a woman’s labour in the kitchen and in a man’s life, undervalued and taken for granted all the time:

Poem No.4

With her broken body

she wove, for the millionth time,

a cup of tea.

‘What colour is this?’

His anger on seeing insipid tea.

‘The various shades of menstrual blood,’ she said.

The sheer poetry of tea!

Poem No.7

Tea-vapour became a cloud.

‘Do not leave, O breath, she said

pressing her centuries-old love on his hand.

Above the parted river’s turbulence,

rain was born.

Meditative poetry bordering on a haiku:

Poem No.10

Tea

In between each drop, the breath rests.

Time breaks off.

In the poem below, one can get a glimpse of the history of the ignominious exploitation of tea-labourers in the process of the production of the premium pleasure-powder of the rich in the early days, which eventually turned into the lifeblood of the proletariat too, like the precious and highly expensive calfskin-bound library edition books of centuries’ vintage are turned into paperbacks for the plebians.

Poem No.12

Steaming red tea

fills decorated cups

and is crowned the national drink.

Even after a century’s passing

the ones whose blood

colours the tea red

are the layam-dwellers.

Here’s the confession of a truly lonely soul, soothed by the heavenly tea.

Poem No.14

In a world with no one,

tea is my companion.

Look at this portrait of a woman labourer in a tea-plantation.

Poem No.25.

The many stretchmarks of pregnancy,

a hundred, hundred thousand black scars

where the leeches have sucked,

shoulders cut to the bone by wicker baskets

and bloodied fingers gnawed away by tealeaf stain,

her body—

A new map traced on the walls of the teacup.

Geetha Sukumaran also more or less follows Ahilan’s pattern in the format of her poems; except for a 3-liner, all are creations of 4-line, 5-line, 6-line, 7-line, 8-line and even a 9-line.

In the poem below, a woman’s body and its abuse, disregarding the dignity of her person, are highlighted by the ending lines borrowed from Meena Kandasamy:

Poem No.4

I brought my fingers to

Her trembling fingers

Which grasped the teacup

Embittered by

The melting memories of the body.

‘To them corpses are superior

To a woman who has been raped,’

She said. *

*https://www.thewhitereview.org/feature/meena-kandasamy

The catholicity of tea and the poet’s cosmopolitan experiences are expressed in the poem below:

Poem No.5

California, Singapore, London:

In all parts,

bodies gripping teacups search

for familiar curves of bone,

folds of skin,

for the remnants of home

welling in their eyes.

A far-stretching recall of Sangam poetry is inserted to satirically describe the taste of tea in a particular café, during a tete a tete between ‘he’ and ‘she’ in the poem below. There is also an indirect hint at the kind of relationship between them.:

Poem No.6

‘Tell me about your love,’ he said

at the café, caressing the teacup.

‘The water in the puddle

back in his village

is certainly not more delicious than this tea’

when, with a laugh she said,

She rose from the springs of Kurunthokai.

![]()

Resonances of the plight of the uprooted Sri Lankan Tamils echo from the lines of the following poem:

Poem No.8

Those

with nothing but memories

keep drenching themselves

in the steam

that curls over

black tea gleaming in a cup.

This is how pure love-poetry is possible over teacups:

Poem No.11

That evening

the sky soared tawny.

They were drinking

the kisses melting in the teacup.

Narrations of bodies in the privacy of the kitchen is described incomparably in the following lines:

Poem No.12

Tea had been served in the hall.

Then, in secret, they sipped the stories

streaming down with sweat from

the spine and the hip

in the kitchen

where, again, fennel and orange peel

simmered with tea leaves.

The tempestuousness of an active youth and its eventual quieting down and the final departure are encapsulated in the following poem:

Poem No.20

Each gulp of tea

is a ripple

A resistance

A protest

A harmony

then, silence.

And later,

The emptiness of a broken cup.

We should drink to that! Tea, in its the concoctions of dissonance.

******

A.J. Thomas is an English-language poet, fiction writer, editor and translator of creative and non-fiction prose from Malayalam to English and has more than 20 titles to his credit. He was on the editorial team of Indian Literature, Sahitya Akademi’s literary journal, as its Assistant Editor, Editor and now is its Guest Editor. He is on the panel of advisors to The Beacon

Vaidheki received a MA in Fine Arts in painting from MS University in Baroda, India. Currently, she teaches art at an international school in Chennai. She is also a freelance artist.

Vidhya Sreenivasan translates short stories and poetry from Tamil. A poet herself, she taught English literature at Stella Maris College in Chennai, India.

PACKIYANATHAN AHILAN born in Jaffna, Sri Lanka, is a senior lecturer in Art History at the University of Jaffna. He has published three poetry collections. An English translation of his poems ‘Then There Were No Witnesses’ was published by Mawenzi House, Canada in 2018. He writes critical essays on poetry, heritage, theatre & visual arts

Geetha Sukumaran is a poet and a bilingual translator in English and Tamil. Her first poetry collection Otrai pakadaiyil enchum nampikkai was published in 2014. Her English translation of Ahilan's poetry Then There Were No Witnesses was published by Mawenzi House, Toronto (2018). She is the recipient of the SPARROW R Thyagarajan award for her poetry. She is the founder of Conflict and Food Studies and a doctoral student in the Humanities program at York University, Toronto.

Thomas. P.Ahilan. Geetha Sukumaran. Vidhya Sreenivasan in The Beacon.

Leave a Reply