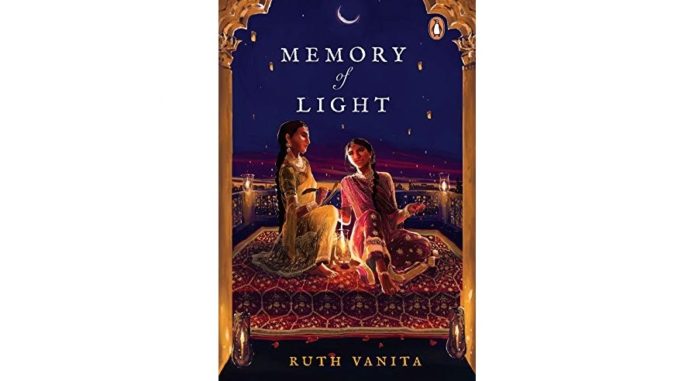

Memory of Light. Ruth Vanita. Penguin Viking India, July 2020. 224 pages

A Prelude

The novel is set in 18th-century north India, and narrated by a courtesan-poet named Nafis, who remembers her life-altering romance with another courtesan, the dancer Chapla, as well as her relationships with family, neighbours, and male and female friends. Historical characters featured in this extract include Sophia Elizabeth Plowden, the British woman diarist who recorded courtesans’ songs, French adventurer Claude Martin’s Indian wife Gori Bibi, and Urdu poets Insha Allah Khan “Insha” and Sa’adat Yar Khan “Rangin”, who wrote about male-male, female-female and male-female amours. Translations of Urdu poetry are by Vanita.

P

ersian kittens were everywhere. Long-bodied and slender, their white silky fur trailing like royal robes, their unwinking eyes appraising and appealing, sapphire, emerald, agate. Looking across the room at an old mirror framed in emerald quartz studded with gems, I watched Chapla laughing in its milky depths. Sitting on the dark red carpet, she smiled down at the kitten walking slowly up her arm and batting at her long plait. Conscious of my eyes and perhaps of Plowden Sahiba’s, she flushed slightly. She was fair enough for the blood to become visible, wine rising in a glass.

We had been asked to a ladies’ get-together at Martin Sahib’s house and here we were; Chapla had run into Plowden Sahiba at Polier Sahib’s house, and then Plowden Sahiba—‘Lizbeth’ Chapla called her—invited her over to her own house to teach her some songs. Chapla didn’t take me along there, I noticed.

The kitten’s tail twitched; two pairs of golden eyes met like patches of sunlight in a glade touching and expanding. Did the kitten sense a being exquisite as itself? I fondled Lizbeth’s little boy, who was at the doll-like age, his hair feathery vermicelli, his skin thick cream. Kishen looked like him, but honey-hued.

‘Won’t you sing?’ Lizbeth asked, tinkling on the harpsichord. She was collecting songs, and had already written down one of the Nawab’s. Much later, I heard that she had them inscribed into a book, with paintings of singers, dancers, musicians. Did we two appear there, as we were that day, one in orange, the other in green?

We sat on the carpet and sang Abru Sahib’s ghazal, which I had marked in the book I had given to Chapla that first morning:

Mil ga’in aapas mein do nazrein ek aalam ho gaya

Jo ki hona tha so kuchh aankhon mein baaham ho gaya

Jis tawajjoh par nazar kar jaan deta tha jahaan

So tawajjoh haa’i in aankhon se’in kyun kam ho gaya

Saath mere tere jo dukh tha so pyare aish tha

Jab se’in tu bichhra hai tab se’in aish sab ghum ho gaya

Raag ki khoobsoorati ke kooch ka dankaa bajaa

Jab gala [gila] mutarib ka yaaron seer se’in bam ho gaya

Two glances met and mingled, a world of loveliness was born

What was to happen happened between those meeting eyes

The world was charmed by the way those eyes met

Alas, why has that regard diminished in these eyes?

When we were together, dear boy, sorrow was pleasure

Since we parted, all my pleasures have vanished

Applaud the beauty of the melody’s departure

When the singer’s lament, friends, moves from treble to bass

Lizbeth clapped her hands in delight, and called her munshi to write down the words. I wondered where Sharad was right now, and Ratan. Had what was to happen happened?

Lizbeth and Chapla went on to the verandah to discuss the English king’s fiftieth birthday celebration, at which Chapla was to dance. I sat with Jugnu and Zeenat, Polier Sahib’s two wives whom he had left behind when he returned to Switzerland, and whom Martin Sahib had kindly taken in. They seemed cheerful rather than bereft, eager to chat and giggle as they made paan.

Chapla and Lizbeth came back, we sang a few more songs, then she and I slipped out into the garden. Which is more pleasurable—being alone together or being with others, knowing that the one they all desire will soon be alone with you?

They call the house Farhat Baksh now, after the Nawab bought it, but to me it will always be Lakh Pera. They certainly felt like a hundred thousand, those trees, whispering round us. We walked, entwined, down a narrow path, to the river slipping by. On the opposite bank, a few jogins were exercising. Oiled muscles, tightly knotted hair, saffron dhotis. A particularly sturdy one threw a discus. Abruptly, she turned to me, her arms tightened. Our toes pressed into the swimming earth. My eyes opened briefly, hers were dark points. Our only kiss in the open air.

For weeks, for months, I may not remember, and then all at once, all together, the scenes rise up, like paintings taken out after being hidden away, bright as if painted last evening, bright enough to hurt the eyes.

We walked back to the house, opened a side door and wandered through the rooms that housed Martin Sahib’s collections. It was as if the contents of a dozen Chowks had been collected together in a shop redolent with cedar, bay leaves and cloves. Shimmering gauzes, velvets, muslins, silks—I could have clothed our whole establishment for decades of performances—coins, medals, jewels, paintings, mirrors, puppets, syringes, fishing rods, books, endless books in many languages, and machines I couldn’t name, though I guessed some were musical instruments. Stuffed peacocks, parrots, monkeys frightening one as they loomed out of dark corners. In that whole fantastical collection, she was the most exotic, the one who held my eyes as she bent over glass cases, from which Burmese rubies and Rajputana emeralds cast unearthly gleams on her face.

‘All their houses are like this, full of curious things,’ she said. ‘Martin, Plowden, Polier, Palmer, de Boigne.’ She placed a large straw hat aslant on her head and struck various poses, mimicking each one’s odd accent as she pronounced his name.

I stifled my laughter in my veil. ‘Like the Nawab Sahib’s museum.’

‘Yes. Almost. He has the largest collection, I think.’

Gori Bibi, Martin Sahib’s chief wife, called us out to the veranda to feed us. Two pomegranates on a silver dish—she picked out the ruby-red seeds and put them in small bowls for us. I was surprised when they melted in my mouth. She laughed.

‘It’s not a pomegranate, it’s a sweet that looks like one. Our cook learnt the trick from Nawab Sahib’s cook.’

‘I’ve heard he can cook yams in a dozen ways?’ asked Chapla.

‘Oh, more, he can cook them differently every day for a month, and you wouldn’t even know they’re yams.’ She poured out tiny cups of wine, scented with special roses from Martin Sahib’s gardens at Najafgarh. She treated us like children and how old she seemed to me then, when everyone over twenty-five was in a category beyond counting. She’s living with Martin Sahib’s other women in Constantia now, where he lies entombed.

Gori Bibi took us up to the roof to see the hot-air balloon. It had carried a man into the sky. Risen above trees and hills as everyone does in dreams. A fortress the building was, with its moat, its drawbridge, its heavy iron doors, and here on the roof its turrets with slits for guards to shoot through. If all else failed, one could escape in the balloon. A tunnel through the sky. The barber who had nicked Nawab Sahib by mistake while cutting his hair, and whom Mordaunt had saved from execution, had been sent up in a balloon instead for punishment, and had descended safely about five miles away.

Then she took us all the way down to see the basement rooms that were partly submerged now. When the river receded during the hot months, they would drain and become cool spaces for Martin Sahib to live in. When we finally got into our boat, the house seemed to shimmer and drift, its top reaching up to the skies, its hidden depths below the river. The sun had not yet set but a full moon was rising amid a few scattered clouds. She sighed and lay down, her head on my lap, then pulled my odhni down so that it shielded both our faces from the sun’s last flare. The boatman was facing the other way.

I was bending over her when someone hailed us, I started back, and there was Rangin Sahib, laughing and bowing. Mir Insha was gazing at the sky, his head on Rangin Sahib’s lap as their boat drifted slowly past. He turned his head without raising it, and smiled at us knowingly.

‘They’ve exchanged turbans, you know,’ I said. ‘They’re brothers now. We should exchange odhnis.’

‘Or bodices. But not transparent ones like yours,’ she laughed, her fingertips, tender as lentil buds, travelling over my silk bodice and pressing the pearl buttons.

‘Those two are on the rise,’ she said. ‘Now that they’ve joined the court of prince Shukoh.’

‘Yes. As soon as he moved here from Delhi, they were introduced to him because of their friendship with his brother.’

‘The one who just died?’

‘Yes. But that’s not the big news for Rangin Sahib. The big news is that Mahtab Baji has decided to take him after all, since he’s prospering. She’s shown Khan Sahib the door.’

‘Really? A happy conclusion for Rangin Sahib, after all that drama.’

Later that night, when we were all sitting together, Mir Insha remarked,

‘What a lustrous evening. It inspired a new ghazal.’

‘Please let us hear it,’ said Ammi politely, and he launched into it right away, still smiling at me.

Chaudahvin taarikh ik abra tanik sa tha jo raat

Sahan gulshan mein ajaayab sair mein dekha tha

Jhilmili si chaadar mahtaab oopar barq ka

Voh dupatta baadle ka tha, jo lahraaya kiya

Yun laga maalum hoti hain yah do pariyaan baaham

Ek ne goya ki saaya doosri par aa kiya

Bu-e gul boli ki aaj aapas mein badli orhni

Chandni khanam ne bi chapla se behnaapa kiya

Khud badaulat to na aa’e aur Insha raat bhar

Aap bin roya kiya, lota kiya, tarpa kiya

On full moon night a small cloud arose

Out in the flower garden, I saw a wonder

A shimmering veil of lightning over the moon

A cloudy veil of fine fabric fluttering

They seemed to me two fairies close together

One drew near, cast her shadow over the other

Flowers’ perfume said they’ve exchanged veils today

Lady Moonlight has become Lady Lightning’s sister

You didn’t have the grace to come, and Insha all night long

Wept, writhed, throbbed alone, without you

Pari, they call us, and for the first time I felt fairy-like, caught in the magical circle of light cast by his verse. As they applauded, several listeners smiled and looked at us.

Next morning, she rehearsed with Azizan, and then we lay in her room eating litchis. I peeled and put them in her mouth one by one as she reclined on a bolster, and she playfully spat out the seeds, aiming for the window. One of the musicians yelled from the street downstairs, demanding to know who was being so rude. Between pretend-scolding and laughing, I asked idly if her name meant anything besides lightning.

‘It has many meanings. It’s one of Lakshmi’s names—she doesn’t stay long in one place, you know. She’s called Chanchal, the restless, the playful one. And it means fickleness, mischief, wine, the tongue.’ She stuck hers, unusually pliant, out at me, then leaned forward to transfer a litchi to mine, and the warning slid away like juice down my throat.

That was the only winter I had something to do with the Christians’ Big Day, the birthday of Jesus. Chapla was taken with the idea of doing something to mark the day. I should have wondered how Maryam was doing, today of all days, but she had disappeared from my mind as a small cloud melts into a flawless sky. Plowden Sahiba had left for Kalkatta a few weeks earlier, so we went to the Palmers’ house, where Chapla had once performed. We knew one of their maids, who took us to her room and gave us that black cake with nuts that I don’t like but that everyone else adores.

I scarcely remember the visit but I remember returning along green lanes through a sunlit winter haze. She was sometimes ahead of me, sometimes behind; we floated and bobbed, two kites playing in the breeze, touching, drifting, then touching again. When we got back, the others were sleeping late as we were not working that evening. She wanted to try making a sweet dish she had seen made in firangis’ kitchens. It had to be steamed in a greased bowl. We mixed milk, butter, sugar, then crumbled bread, nuts and raisins into the mixture. In the liquid our fingertips touched, pressed, she raised hers dripping and put them between my lips.

‘Delicious,’ I said, sucking, and then pulled her down to the coal-stained floor.

‘There’s water on the fire for a second pudding,’ she protested weakly. ‘I overfilled the pot, it’ll boil over.’

‘Let it.’

‘We should cook more often,’ she said later, laughing, after the water had boiled over and the pot was scorched. ‘Seems to inspire you.’

Those few months of being together day after day are a fixed, unmoving circle of light. I remember only a few special days. Is that what happiness is—the cessation of happenings? It was winter but felt warm, waking every afternoon cushioned in rose petals, and going to bed in the last reaches of the night cradled in velvet.

Madan was the only person I told. Pleased to be singled out for my confidences, he took us out to an inn. This was a new enjoyment to me; she had stopped at inns for meals on her many travels. He obtained a private room. In the open pavilion overlooking the river, men gathered, two female singers from a kotha less prominent than ours sang, and a dancing boy performed, all of them stopping at intervals to puff on a hookah. Our room too had a view of the river. Bare-chested servers ran in and out, with hot breads of various kinds. The food was interesting, spicier and greasier than we were used to.

Madan beamed benevolently on us. She got up to visit the bathroom, and I accompanied her. As we closed the door behind us, I daringly blew out the candle and pulled her around to face me in the sudden darkness.

Early morning on Holi, I couldn’t find her anywhere. Heera found me first and soaked me in the orange of palasa flowers. With a pitcher of red hibiscus water, I went next door, saw Ketaki Mausi embracing Ammi and asked her where Chapla was. ‘Haven’t seen her, bitiya. Go look in her room.’

I looked into all the rooms but they were empty. Everyone was outside, screaming and getting drenched, some in the backyards, some in the back alleys. A troupe of revellers in costume came in from the alley. One in a saffron sari, no bodice, barefoot, bare-armed. That hair cascading like a waterfall gave her away even before I saw her face. ‘Look, look, Heera,’ I pointed over the many intervening heads. ‘Look at my gu’iyaan.’ In my excitement, I said it, but perhaps no one heard, amidst the screams. Many others were looking too, all the free-eyed, freethinking men, young and old. Why is open hair so enticing?

The house rang with screams and laughter, then subsided into torpor as we bathed and then retreated, tired, to our rooms. But her mischievous mood lingered. In my dressing room she stood, her back to me, draped in a long and heavy violet veil, edged and spangled with gold, while I pulled on a lehnga to be comfortable.

‘Just hold up a mirror for me to see how this looks,’ she said. There was never any shortage of mirrors in our houses. I picked up a rectangular hand-mirror, then gasped as she half-turned, clad only in strings of pearls, emeralds and rubies.

In the late afternoon, Mir Insha dropped in, on his way to the evening festivities at the palace. He was in a luxurious marigold-coloured outfit, all aglitter. ‘You and I look alike,’ he teased her, eyes sparkling with mischief. ‘I was a fairy-faced one in my youth, believe it or not, Chapla Bai.’

‘Oh, I believe it. You’re still beautiful, Masha’allah.’

*******

Ruth Vanita taught at Delhi University for 20 years and is now Professor at the University of Montana, where she teaches gender and sexuality studies, Indian and British literature, and Hindu philosophy. She volunteered as founding co-editor of Manushi (India’s first nationwide feminist magazine) for 13 years. She is the author of several books, most recently Gender, Sex and the City: Urdu Rekhti Poetry in India 1780–1870; Dancing with the Nation: Courtesans in Bombay Cinema. Her first novel, Memory of Light, appeared from Penguin in 2020. She is now completing a book entitled The Dharma of Justice: Gender, Varna and Species in the Hindu Epics.

Ruth Vanita in The Beacon

Leave a Reply