M.G.Vassanji

O

ne afternoon at a tea following a seminar on Gandhi, in Shimla, India, to my utter astonishment I was approached by a woman who spoke to me in Swahili. Veena Sharma—small, soft-spoken, and sari-clad—was not from Africa but she had spent some years in Dar es Salaam in the 1970s, broadcasting for All India Radio. She seemed to know all the important people in Dar, people whom I, a mere student from modest Kariakoo and Upanga, only read about in newspapers. Her interest in Africa remained. Four weeks later, at the tea lounge of the India International Centre in Delhi, Veena introduced me to a woman called Urmila Jhaveri.

Coincidences happen; this one seemed miraculous. As I stood chatting with Mrs Jhaveri in a Gujarati as formal as I could muster, I couldn’t help but keep wondering at the improbability of this meeting. We both came from Dar es Salaam, she was a fellow mhindi from Africa, that was enough to be excited about. It was also one more demonstration of the fact that East African Asian identity is real, and becomes evident especially outside of that milieau. But there was more to our meeting, and this my new acquaintance could never have guessed.

The name Jhaveri takes me to one of my earliest memories: I was eight, my family had moved to Dar from Nairobi, and my mother had opened a shop in a new building on Uhuru Street, on the second floor of which we now lived. Independence was around the corner, and the first-ever general election in the country was about to take place for representatives to the Legislative Council. White-and-black posters with photos of the candidates had been pasted on the buildings of Gaam and Kariakoo, exhorting, “Vote for Jhaveri!” or “Vote for Daya!” Young Asian men came around to canvas, exhorting, “Ma, are you going to vote?” Daya was the doctor who treated my grandmother, and he had my mother’s vote. He was from our own community, and that was the extent of our politics. KL Jhaveri, a criminal lawyer, however, had the backing of Nyerere—leader of the African TANU party—and won the seat. Years later he wrote a book about his political life, Marching with Nyerere: Africanisation of Asians. The subtitle is significant. It is a bold assertion, it is unequivocal, it speaks to the time.

KL was from Dar, Urmila from Pemba. She missed Dar, she told me in Delhi, and all its familiarity, having left only the previous year because KL needed constant medical attention. Their daughter lived with her family in Delhi. When I visited them at their suburban home a few days later, KL was seated on a sofa, an extremely frail-looking man, literally skin and bones, shorn of all flesh. He was lively, and complained about the Indian production of his book. In Delhi he was keeping himself busy writing, though you wondered how in his fragile state he managed even to finger the keys. Urmila and I, in Tanzianian Indian fashion, chatted over bhajia and chai. She said she was writing her own memoir. It would be a valuable contribution to East African history, though I wondered if it would be allowed to see the light of day.

As the call for African freedom rose in the 1950s, and subsequently for real freedom—from “neocolonialism”— in the years thereafter, the Asians faced a choice of loyalties. The shopkeepers and small businesspeople, in the manner of their class everywhere, were nervous about change. Most of them merely eked out a living; they had been protected by the colonial administration, and the only nation they knew was their small and exclusive community. Our long-standing barber, Madhu Bhai—who passed by our shop every month to cut my brothers’ and my hair on the pavement, in full public view—was one of those who succumbed to his fears and left for Gujarat, much to my sorrow.

Among the professionals and the educated, however, there was an elite that responded positively to the call for freedom. The Jhaveris reflected the optimism of that class—educated abroad, still in their thirties, and savvy about the world. Well aware of India’s own struggles and excited about African independence, they moved in the enlightened and secular circles of the Asian Association (founded in 1950). The questions they posed themselves, often expressed in their bulletin, The Tanganyikan, concerned the future of Tanganyika—which they saw as democratic and nonracial—and the role of the Asians in it. In a report to the Association, KL Jhaveri for example opposed the proposal of the government-supported Capricorn Society, which would restrict the role of the Africans using economic and other criteria and called for a federation with Kenya and Rhodesia. (11) In an eloquent article, Amir Jamal wrote, “The Asians of Tanganyika…have a great opportunity of making a significant contribution to build up a strong and stable society. What is needed is a complete change in their outlook towards the realities.” (15) This at a time when many Asians feared that come independence the Africans would simply walk in and take over their shops.

Sophia Mustafa, of Qadiyani (Ahmadi) background and wife of a judge, ran for the Legislative Council in the Moshi area. Soon after that election, she wrote a book titled The Tanganyika Way, and it quite catches the excitement, the freshness, and perhaps the naive idealism of the period. Wearing a sari and not very fluent in Swahili (she was born in India), she enthusiastically embraced the idea of citizenship above race, and exhorted fellow Asians to think beyond communal and racial identities. In a speech she gave to the Asian Association, she said,

I…appeal to you all here to forget your various sects or communities as such, and all consider yourselves as Asians. And, when you have succeeded in dissolving your mutual differences and antagonisms, you will go further and sink your race as a distinctive factor and consider yourselves as Tanganyikans. The Tanganyika Way (83)

A dramatic and bold statement. Sophia Mustafa came not only from a racial minority in Tanganyika, but also from a small and persecuted minority among Muslims; and the violence of the Partition of India was recent memory. It is not surprising then that she spoke for dissolving differences among Asians. She envisioned a future in which Asians did not only run shops or work as white-collar professionals but also farmed and worked with their hands. (The Gujarati trading class did not traditionally dirty their hands.) In a moving passage she describes the moment when the constitutional conference of March 1961 concluded in Dar es Salaam, and a garlanded Julius Nyerere emerged from the hall to be driven slowly in a motorcade, holding up a placard that said “Independence 1961.” (143) The governor of Tanganyika turned to her and said, “Was this not the day we were all waiting for, Mrs Mustafa?” (143)

Her book ends with a collective rallying call for the new multiracial Tanganyika. But much more was at stake in the complex and tumultuous times that followed. There would come the revolution of Zanzibar, with the horrific racial violence few could or can explain even now, the attempted coup in Tanganyika, the union with Zanzibar, the war with Amin’s Uganda, and the decades of socialism and cold war politics during which many Asians left. She herself left politics, and like Urmila Jhaveri much later, she had to leave the country in older age for the sake of the health of her ailing husband. I met her in Toronto in the 2000s, and she died soon afterwards shortly after her husband. She had written two novels, one of them set in Kenya, where she had spent some time.

The most powerful, admired, and enigmatic Asian in politics, however, was Amir Jamal. Educated in India, where in 1942 he happened to attend a Congress meeting in which Gandhi gave notice to the British to “Quit India,” Jamal kept his distance from communal affiliations. From 1961 to 1980 he held various ministerial positions in government, including that of minister of finance. The website of the Brandt21 Forum (of the Centre for Global Negotiations) writes,

Jamal’s utter integrity, dedication and selfless service, along with his political ability, were recognized throughout Tanzania, and Jamal was repeatedly elected with ever-increasing majorities from predominantly African constituencies.

He died in 1995 in a Vancouver hospital after a year of illness. According to Sophia Mustafa, Nyerere made a call to Vancouver begging that the body of his friend be returned to Tanzania to receive full honours. Unfortunately, this did not happen.

Because of the violence of the freedom struggle in Kenya and, since early colonial days the presence of white settlers, whose ideas about the country’s future leaned towards the models of South Africa and Rhodesia, Kenyan politics was always more colourful and louder than that of Tanzania. Kenyan Asian demography was also quite different from that of Tanzania, a fact often not realized or simply ignored; it comprised not only the Gujarati shopkeeper class but also the descendants of the Punjabi indentured workers who had come to build the railway in the early twentieth century, and a professional elite—doctors, lawyers, teachers—who arrived much later. The presence of the settlers meant that business was more profitable. The Europeans—the whites—spent more freely. Big game hunters and visitors, among them Teddy Roosevelt, the Prince of Wales, Ernest Hemngway, and the castes of Hollywood African adventure movies, would have been outfitted at least partly at the Asian shops. Tanzanians, on the other hand, were for the most part the easy-going Kutchi-speakers who began their African lives in Zanzibar, and continued in Dar es Salaam, where their customers were Africans. Tanzanian Asians were largely also Swahili-speakers, unlike their Kenyan counterparts (with the exception of Mombasa).

And yet, Kenya had—perhaps because of better education and better economic status–produced some remarkable Asian activism, since as far back as the 1920s, in the form of legal and publishing services for African activists (including Jomo Kenyatta), opposition to apartheid, and promoting labour relations. Zarina Patel in her study of the businessman A M Jeevanjee, who was also her grandfather, writes of the Asian contribution to Kenya with some passion:

Led by AMJ and Manilal Desai, [the Asians] put a halt to the settlers’ bid for self-government… They enabled Harry Thuku to meet with Marcus Garvey, Mbiu Koinange to travel overseas… They established newspapers in Kenya and gave access to their presses to the African nationalist movement… [They] were instrumental in founding the trade union movement, which was a leader in the struggle for independence. In fact, the first public demand for Kenya’s independence was made by Makhan Singh, an Asian… [It was] Ambu and Lila Patel who spearheaded the Free Jomo Kenyatta movement. Challenge to Colonialism 220-221

In the 1950s, Indian prime minister Nehru’s representative to Kenya, Apa Pant, got on settler nerves by being friendly with the Kikuyu, and many Asians from the Nyeri region recall hiding or giving rides to Mau Mau suspects during the Emergency, when anyone could simply be detained and Kikuyu movement was highly restricted.

After independence, however, the potent brew of Kenyan politics, with its corruption, tribalism, and violent vendettas made it impossible for the Asian minority to raise its voice. They were too small in number, they were a soft touch—mostly traders and white-collar workers—and they were uncertain and nervous. Still, in those early years in Kenya, the debates about citizenship and African identity among Asians were intense. The young and educated were keen to be a part of politics and nation-building. But in the clamour for new opportunities, amidst all the tribal and personal rivalries, the Asians were too easily shoved aside. Makhan Singh, who had spent ten years in colonial detention, was ignored by the new leaders. Pio Gama Pinto the journalist, who spent four years in detention for his support of the Mau Mau and whose activism continued, was assassinated. In a climate of increasing corruption and state violence, it was far too easy to intimidate the Asians, blame them all for exploitation and racism—to call them the Jews of Africa who bred uncontrollably and dangerously. “To be branded an Asian,” wrote the playwright Kuldip Sondhi, “and be damned for it is an experience every Asian undergoes in Africa.” On their part the Asians remained insular: it was in their character. They could join in nation-building activities, but at the end of the day they reported to family and community. Their predicament was put succinctly and with some bitterness by a Sikh gentleman, who was quoted in the papers as stating, “The problem with us Asians is that we are not white enough to be white nor black enough to be black.” The white man who had been top dog during colonialism now came as a benefactor and representative of Europe. He was cool. The Asian “Jew” moved to the background.

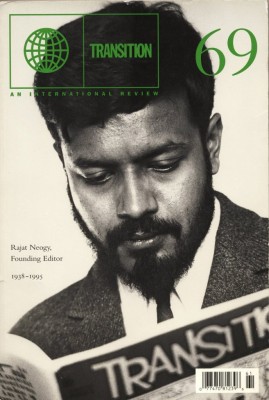

In December 1995, in The New York Times there appeared an obituary of a Ugandan Asian. London’s Independent carried his obituary the following month. This in itself is remarkable. Uganda, except for war or disease, is hardly of global interest, and the Asian from there even less so. The deceased, aged 57, was Rajat Neogy, someone special. He was founder and editor of the hugely influential literary magazine Transition that came out of Makerere University in Kampala in the 1960s. Neogy was born in Kampala in 1938 and had studied in London. There’s not much known about him that’s published, but he had blazed onto the literary scene. Transition’s pages gathered a remarkable array of literary and political luminaries—James Baldwin, Wole Soyinka, Chinua Achebe, Kofi Awoonor, a young Paul Theroux, Christopher Okigbo, Ezekiel Mphalele, Okot p’Bitek, Tom Mboya and Kenneth Kaunda. Benjamin Mkapa, the future president of Tanzania was associate editor. Ali Mazrui followed him. Said Henry Louis Gates Jr of Harvard about Neogy after his death, “This man created an African-based journal of letters that everybody in the intellectual world, it seemed, was excited about. He fought fascism in blackface, and that was rare and courageous.” Ngugi would credit the publication of a story in Transition as a turning point in his life.

The post-independence 1960s was a special period for Africa. In keeping with the general intellectual fervor and political idealism of the period, Makerere University had became a literary hub. A new literature was in the making, and the young people were busy defining their role in it. In 1962 the first African Writers’ Conference took place at Makerere, a milestone that is still remembered. Soyinka, Achebe, Ngugi, Nkosi, Taban were present, Soyinka later saying of it, “We went to join a convocation of writers and intellectuals from every corner of the continent… We were on safari on African soil: the signs along the way all showed the same slogan: Destination Kampala! Africa’s postcolonial renaissance.” There would have been few other places in the world where there was such an excitement about new literature, new ideas, and new politics. The inspiration arrived at this conference for a new publishing imprint of literary titles called an African Writers Series, which was soon launched by Heinemann in UK, with Achebe as the series editor. The excitement reached as far as my high school in Dar, where literary competitions were held, new drama was produced, and a parade of literary luminaries passed through, including Chinua Achebe. When many years later my first novel was published in this series, it was for me a moment of arrival. The headmaster who brought Achebe to our school, Peter Palangyo, himself turned out to be a novelist.

Besides Neogy, the editor of Transition, several Asian writers were a part of this emerging East African literary consciousness centered in Kampala: Bahadur Tejani (b 1942 Uganda), Peter Nazareth (b. 1940 Uganda), Amin Kassam (b. 1948 Kenya), and Yusuf Kassam (b. 1943 Tanzania). All were near-contemporaries of Ngugi wa Thiongo (b. 1938), who was already claiming attention as J T Ngugi. Here was an opportunity for forming an Asian African identity through literature.

It was typical of those times that Wole Soyinka in his anthology Poems of Black Africa (1975) includes the poetry of Amin Kassam, Yusuf Kassam, and Bahadur Tejani. “Black” in the title denotes southern Africa, embracing while not denying ethnic or racial particularities. It is a generous anthology, as is evident from Soyinka’s introduction. But—one imagines, from this distance in time—for these young Asian writers the exuberance and power of the African literary consciousness around them must have been intimidating. Theirs was not an easy place to be. There was first the whole historical baggage of India to confront; education requires an honest appreciation of identity and history, and India surely had to be confronted—it could not be dismissed simply as poor and out there. But more than that was the all-consuming presence and pull of community and family—through which, in fact, India manifested its presence in most of us, through religion and language, customs, foods, and traditions. (Nazareth was a Goan; Amin Kassam and Bahadur Tejani, Khoja Ismailis.) And finally there was the consciousness, all the time, especially in Kenya, of being the Other, an insecurity enhanced by frequent discussions of the “Asian question,” and frequent racist provocations by African demagogues.

To write meant to write with your whole being, and that was hard to do, with family looking on, the community watching nervously, and presumably the father wondering what the future was in all that scribbling: why not marry and settle down in the age-old fashion? And so, whereas the poetry of Okot p’Bitek, for example, is firmly grounded on African soil and fully confident of its intent, and Taban Lo Liyong writes an essay with provocative gusto about the barenness of East African writing, while the black African poets struggle with their gods and tangle with their native languages and speech rhythms, their village life and urban squalor, all the three Asian poets mentioned above, and several others who wrote occasionally, seemed largely to prefer the safety of the universal, the minimal, the casual observation—and even the obscure and abstract, shying away from their gods and languages, their traditions and personal lives. To ground their creative output in Africa, it would have to be grounded in Asian Africa, their own lives and experiences as Asians from their respective communities, which could not have been easy—on one hand to produce a genuine aesthetic and make yourself understood and accepted, on the other, not to offend the home gallery. The result was a nervous uncertainty to the writing, a wavering aesthetic.

In some of his poetry, however, Tejani directly confronts his dilemma of being different, an Indian in Africa, revealing a personal anguish that is a consistent thread. Tejani is particular is deeply attracted to the physicality of the African, compared to the bloodless reserve and interiority of the Asian. (This is a theme that occurs in Nazareth’s work too.) In one poem, “Lines for a Hindi Poet,” Tejani uses a scene witnessed in a New Delhi park—two dogs freely mating—to call for a loosening of Asian attitudes to love and sex. The result is an incantation:

Lord! Lord!

Let the brown blood

rediscover the animal

in itself,

and have free limbs

and laughing eyes of

love-play.

In “On Top of Africa,” the poet again laments the difference, capturing vividly and in surely more ways than one the anguish of the Asian African:

I shall remember

the dogged voice of conscience

self-pity warring with [the] will

of the brown body

to keep up

with the black flesh

forging ahead

on the way

to Kilimanjaro

There were some plays written by Asian writers, some of them for stage, some for radio. Peter Nazareth wrote for the radio, Ganesh Bagchi wrote for the stage, Kuldip Sondhi wrote for both radio and stage. These plays, some of them minimalist and experimental, others more situational, were produced for educated multiracial audiences who could not be bothered with cultural specificities. In Bagchi’s “The Deviant,” for example, a man and woman, who perhaps live together, discuss whether they should get married; the characters could be anywhere, and (almost) anybody. In a radio play, as Shirley Cordeaux of the BBC wrote in her introduction to Nazareth’s Two Radio Plays, “sound is everything.” In the BBC productions of these plays, the cast is in fact from several different countries (though not from East Africa), actors who happened to be available in London at the time. Kuldip Sondhi of Mombasa wrote plays, for radio and stage, that were more located locally. It is hard to imagine the radio play “Devil in the Mixer,” which is set mostly at a construction site, with its easily recognizable voices, produced anywhere else but in Kenya; it could easily have been staged. “Undesignated,” which won a prize, is about the anxieties of promotion in a government office in newly independent Kenya, where the protagonists are Hindu and Muslim Asians, and Africans. Sondhi, who was born in Lahore in 1924, is from an older generation than the Makerere crop of young writers. His plays of the period, though set in realistic situations, exist in the interracial borderland. To see the inside of an Asian home or an Indian dance on stage, or invocations to the gods, one would have to go to a community drama in Gujarati or Punjabi, intended for “insider” audiences. The Khoja Ismailis in the 1950s regularly staged plays with religious and family-value motifs that came with ready-made Hindi film songs.

Fiction, however, gave scope for in-depth and honest portrayals of Asian life. In his novel, Day After Tomorrow (1971), Bahadur Tejani pursues his theme of Asian inadequacy. His protagonist Shamsher, who grew up in the countryside, is in love with Africa—its simplicity and honesty, its grace; and he dislikes the Indians around him. He observes, “The estrangement with their environment and with the people around him made him feel that all Indians were the remnants of a decaying civilization.” One detects echoes of Naipaul. Elsewhere, witnessing a scene at the Kampala football stadium, he observes:

The African people, full of physical vigour and joy of life, flocked in large crowds to watch their players perform. The whole place rang with ululations and joyous shouts so that the very walls of the stadium trembled with it. As if lusting to participate in the struggle.

And,

He was captivated by the graceful movement of the Muganda female. Her elegant dress that exaggerated her back-swing. The sharp delicate features and the glow of the fresh skin reminded him of the sun dying in a clash of hot sympathy for the earth.

The novel is sketchy and schematic, simple and romantic, forgiveable in a young man’s first effort; there is no complexity of characters or even ideas; it examines Asian life very perfunctorily (compare Ngugi’s treatments of Kikuyu life, which are so grounded in the earth of Kenya.). The Asian woman is hardly observed. In a sari, one might argue, she would look as elegant as Tejani’s Muganda female, with a “back-swing” as well. Is a taboo at work here or simply disinterest? The novel however has some beautiful descriptions of Asians in a rural setting, and the awesome, looming greatness of the African continent. And it does explore the idea of what a new Asian African might be. In his Epilogue, in which the author very pessimistically addresses the reader directly, he rejects the idea of the separation of races, very much as Sophia Mustafa had propounded:

…we in East Africa, numbed by our pluralities, have decided to erect the one firm ideal of multi-racialism: that is, to keep quiet. To display a deliberate sense of graceful relaxation which is meant to show the non-existence of tension.

For Tejani, then, as for Sophia Mustafa, a mere racial coexistence was unacceptable. There had to be a single identity.

A new East African literary consciousness had thus emerged. The Asian writers were part of it and spoke confidently of a collective we and a collective future. “What is an East African culture?” Neogy asked, for example, in his editorial to the first issue of Transition.

And then suddenly, everything changed. Neogy was put into detention in 1968 for criticizing the Uganda government, after which he left Uganda. He died in San Franciso. Idi Amin appeared and expelled the Asians of Uganda (“the engineers of corruption”). Tejani ended up teaching in New York, where he would write fantasy and comic fiction and poetry. Amin Kassam and Yusuf Kassam disappeared from the literary scene, and Peter Nazareth, after two novels, became a literary critic in Iowa.

That creative spark, inspired by the promise of a new dawn, a new Africa, with all its excitement and uncertainty, was gone.

Was that creative spark, that hope, doomed from the beginning? A cultural magazine is a broker, a provider of sorts—was Neogy and his Transition a mere broker, a deliverer of goods—that typical, stereotypical role of the Asian in Africa?

Peter Nazareth’s novel In a Brown Mantle, written just before Idi Amin had his dream, presents an extremely pessimistic portrayal of the Asian’s fate in Uganda. (The country is actually given a fictitious name, and the Asian home and family are hardly portrayed.) In the novel, Deo D’Souza is an idealistic young Goan who leaves his civil service job to work for the political party that brings the country its independence. He is assertive about his African-ness. But he is never fully accepted –“When will you return home?” is a taunt he often hears. Fed up of the racism, and the political corruption and betrayal, he leaves the country, saying, “Goodbye Mother Africa—your bastard son loves you.”

A tough, a moving testament. But one has to pause here: loved you? no longer loves you? What then does it mean to belong? There were Asians who never left Uganda even after Idi Amin’s dictat—and were never heard of again. I met an Asian woman in Vancouver who told me, after visiting her Ugandan homeland more than twenty years after Idi Amin, “I did not mind seeing that Africans had taken over my father’s business. At least that way they could come up.” That’s belonging from the gut.

However, for three decades Peter Nazareth championed African literature. Dozens of writers passed through his department in Iowa City. (He was also instrumental in the publication of my first novel in the African Writers Series.) But he never visited his native Uganda. I have convinced myself that the turning away from Africa by many Asians was not from bitterness, entirely, but also from grief.

Those Africans who cheered Amin’s decision, in East Africa and beyond, could not have imagined that their boxer hero would end up killing thousands of Africans within a few years, turning the Nile red, and would provoke a war with Tanzania that would cripple the area economically for many years; that the goading racist stereotypes, so manifest in the pages of the Uganda Argus at the time, were reminiscent of the antisemitism of Europe of three decades before; that the mild ethnic cleansing in Uganda was but a foreshadowing of the genocide of Rwanda. (On their way to India, many Asians left Kampala for Mombasa in sealed trains.)

In a 2012 article in the electronic African magazine Pambazuka, Ngugi paid a tribute to the Asians of East Africa, pointing out their contributions. In particular he mentions his days at Makerere:

The lead role of an African woman in my drama, The Black Hermit, the first major play ever in English by an East African black native, was an Indian. No make up, just a headscarf and a kanga shawl on her long dress but Suzie Wooman played the African mother to perfection, her act generating a standing ovation lasting into minutes. I dedicated my first novel, Weep Not Child, to my Indian classmate, Jasbir Kalsi… Ghulsa [Gulzar?] Nensi led a multi-ethnic team that made the costumes for the play while Bahadur Tejani led the team that raised money for the production.

He adds:

It was not simply at the personal realm. Commerce, arts, crafts, medical and legal professions in Kenya have the marks of the Indian genius all over them. Politics too, and it should never be forgotten that Mahatma Gandhi started and honed his political and organizing skills in South Africa …

If only he—or someone—had said this thirty years earlier. In an issue of Transition in 1967, Wole Soyinka had issued a scathing warning to African writers: “…would a stranger to the literary creations of African writers find a discrepancy between subject matter and environment?” There was a “lack of vital relevance” in the writing, he charged. “Reality, the ever present fertile reality was ignored by the writer and resigned to the new visionary—the politicians”

******

M.G. VASSANJI is the author of six novels, two collections of short stories and two works of nonfiction. His first novel, The Gunny Sack, was the winner of the Commonwealth Prize for Canada and the Caribbean. He has won the Giller Prize for both The Book of Secrets and The In-Between World of Vikram Lall, and the Governor General's Literary Award for Non-Fiction for A Place Within: Rediscovering India. His novel The Assassin's Song was shortlisted for both the Scotiabank Giller Prize and the Governor General's Literary Award for Fiction. He was born in Kenya and raised in Tanzania, and attended university in the United States. He lives in Toronto with his wife and two sons.

Leave a Reply