Joginder Paul

The Slump

Manda

T

he patrons of the United Club of Nairobi took great pleasure in being known as affluent intellectuals. They paid approximately 30 pounds a year to gorge on the mutton samosas in the club’s garden restaurant, sat listening o conversations between the rich and powerful in the big hall, had a weekly dinner, and every evening mingled with the other members at the bar, totting up a hefty bill while presenting their contrarian opinions on various topics.

According to the rules of the club, people of all races and communities could become its members. But, in truth, the blacks were represented only by the club’s African waiters. At the last General Body Meeting, an Asian member had raised the issue and asked a European Committee Member about why African people did not like to become members at the club. After pondering on the gravity of this query, the High Council had finally reached the conclusion that Africans had not yet become civilized enough. Therefore they were still bereft of the niceties required to lead a socially fit life.

Every time a new member set foot in this large hall of the club, he slowed down, hesitated, and his voice dropped to a whisper. Such was the sight that greeted him- of old members, spiffy in their rich garments and full of elaborate gestures. But once he mingled with them for a while his image sat well with theirs, and he became part of a very happy frame. When dear Mrs Becky runs through the list of merits of a pickle that she has made all by herself, he also relishes the mischief dancing in her eyes. Whenever the tall, middle-aged Bull starts off about his department’s service to the nation, he begins to look at him in wonder and admiration. While listening to the useless son of the richest in an of the city – Narayanji – holding forth he would assure him that the entire country would very soon be forced to acknowledge him as a path:-bearer. And finally, when all the members would be delighted at his behaviour, he would return the4 intimate looks as if to say, ‘Now you too say something complimentary about me.’

‘Ashofi Saheb, your observation is very deep indeed.’ ‘Ashofi Saheb, read your analysis ·in The Kenya.Times. Till date, I haven’t ever seen a better essay on economics.’

‘Ashofi Saheb, it’s amazing how well you shave. Which blade do_ you use?’

When people turn away from lesser gods and begin to venerate one Supreme God, the earthly entities begin to worship each other amongst themselves.

As was their wont, everyone was present at the club that day. When Harmuzji, sitting at the left-hand corner close to the bar counter, lost his hand at cards, he bought every member of the group a double peg of whisky in keeping with their agreed wager.

‘Arre, Harmuz ji,’ Radha Krishna, sitting at another table with another group, headed their way urgently, waving a newspaper at them. ‘ ok at this Harmuz ji ‘ he thrust the newspaper forward, ‘Shyam ji Heer ji have gone bankrupt.’

‘Bankrupt?’ Doctor Inam asked, raising his whisky glass to his lips in no seeming hurry. He was already thinking of how, perhaps, Shyam ji would very soon suffer a heart attack a nd send for his services. ‘How unfortunate.’ He appeared extremely displeased at realizing that his whisky glass was suddenly empty.

‘Shyam ji is a very smart man.’ Harmuz ji took his eyes off the newspaper. ‘Even in this state of bankruptcy he has profited by 15,000 pounds.’

‘How’s that?’

‘Two or three months back, he had deposited this amount under the name of his eldest son and sent it out of th_e colony.’ Harmuz ji had already made up his mind about opening up an account in a bank in England in his wife’s name. He turned his loving gaze upon his wife to encounter her loving gaze upon Narayan ji’s youthful, unemployed son’s luscious hair as she enquired sweetly why he no longer visited their home.

‘Why are so many Asian companies facing bankruptcy these days?’

‘You do not understand Mr Goodluck, the traders are suffering very badly these days.’ Radha Krishna suddenly felt crushed like an insect, flowing away with the tide. His firm was facing severe losses for some months now. ‘We have witnessed a trade slump like this for the first time in the colony. There are men everywhere, swarming, but you cannot see a single buyer.’ ‘Yes, there is indeed a slump these days,’ Narayan ji’s son piped in, ‘my father was mentioning that at least twenty workers will be laid off in our factory soon, three Europeans and seventeen Asians. Mr. Goodluck, your glass is empty. Boy!’

‘In our post office, ninety men will be relieved next month,’ said Mr Goodluck, a high-ranking official at the GPO. ‘God alone knows how this slump has descended upon’. us so suddenly.’ ‘This is a massive slump Mr Hardstone,’ Ashofi Saheb began, ‘today, countries across the world are surviving only because they are supporting each other. In my opinion, it is because of the current trade slump in England and America…that has affected our condition.’ Ashofi Saheb looked all around, his haughty, self-admiring eyes checking out the faces before finally colliding with dear Mrs Veni’s impish ones, barely managing to steady themselves. ‘Why has Mr Veni not come to the club today, Mrs Veni?’

Mrs Veni responded, ‘He has an important case at the court tomorrow, he’s preparing for it,’ as if to say ‘how- doeshis absence matter, your presence here is enough’.

Ashofi Saheb’s joy knew no bounds, ‘But you must believe me when I say that this slump will not last forever.’

‘When I first arrived here in 1950… ‘ It was Shamsher Singh’s habit to listen to his own voice very keenly, ‘You could not spot even a single poor person.’ An African waiter, acting on unspoken orders, came and stood before Shamsher Singh with a cup of coffee laced with brandy. ‘You would not spot a single poor person, no one was unemployed and, in fact, itwas difficult to find people to do your work. But today, even for an ordinary post, there are twenty applicants running around to get it.’

‘How well I speak .in English,’ Shamsher Singh’s mind began its familiar self-praise, ‘how amazingly well! Each one of these people seem to be deeply enamoured by my eloquence in the language.’

‘You are right Mr Singh. My last month was wasted entirely in selecting suitable candidates for two of my clients. My eyes were so tired from reading the applications. Every day someone or the other would land up at my bungalow with a. recommendation.

Now you tell me, how long can a man who gets two thousand as salary waste his time on these trivial matters?’ The speaker’s gaze darted from person to person, as if saying ‘I take home a monthly salary of two thousand did you hear that?’ Then he sat back and relaxed, lighting his American cigar and puffing away deeply at it with satisfaction.

‘Yes, but from where has this chill crept into the market?’ Ram Krishna blurted, bewildered by his losses. He picked up his glass and emptied it of the Stout in a big gulp.

‘In my opinion this is not a massive slump, according to the rules of trade.’

The glass of Stout ran its course through Ram Krishna’s body and made him anxious. He interrupted Ashofi Saheb, ‘But what is the real lesson in all this?’

‘The real lesson?’ Narayan ji’s son unfurled himself and stood up, completely under the influence of his whisky. He turned to Mrs Harmuz, ‘What is a real lesson Mrs Harmuz ji? Today you must absolutely explain the meaning of a real lesson to me.’

Mrs Harmuz ji gently coaxed him back to his seat and began to play lovingly with his beautiful locks.

Harmuz ji loo ke·d upon both of them and decided that the new bank account in Englanl was certainly not going to be in his wife’s name.

‘Mr Ram Krishna,’ he said, ‘the real lesson of this slump is that we-c an no longer trust each other as we used to.’

‘Now we can see our future before us.’

‘The market has grown far more competitive.’

‘We are losing our money.’

‘No politics please.’

‘But I insist on asking, what is the true lesson of this slump?’ Ram Krishna wanted .to place another order for whisky but he remembered that he had invited his income tax advisor home for dinner. A five-year old tax return had got into a problem. He rose up to leave, ‘I still do not understand the real learning from this slump.’

When all the members of the club had left one by one in their cars, then the African servers quickly finished the rest of their chores and collected together at the servant’s quarters. Mesuki looked around at all of them smiling impishly, and fished out a bottle which all the bearers of the dub had quietly topped up with the leftover drinks from the members’ glasses.

‘Lozego, let us begin.’

• ‘There’s quite a fill of cocktail here today.’

‘Harmuzji’s memsaheb did not even touch her last peg today.’

‘Once her fingers begin to dance in that boy’s hair, she usually forgets her pegs.’

‘That rascal Hardstone doesn’t leave even a drop.’

The waiters all began· to pour out the cocktail into their glasses.

‘Matele, Goodluck’s mem saheb is a very interesting woman, much more so than food.’

‘Why aren’t our women like them, friend?’

‘It’s the perfume they wear, buddy, but this woman is naturally attractive. Living a carefree life makes even a sheep look wondrous.’

‘Forget it, what’s all this you are talking about,’ . the old Metheka couldn’t stop himself. ‘Talk about something important, Mesoki, what is this slump they were talking about? The sahebs were saying that a huge slump has hit our country.’

‘Slump?’ The half-drunk Mesoki was thinking ‘let me empty my glass and then I can explain to them what this word means’ · ‘These people were only talking about their own businesses, rafiqui, ‘ Maragori said.

‘I think this slump must be something really attractive that people are drinking double the usual amount.’

‘Mesoki, please tell us, what is this slump?’

Mesoki quickly emptied his glass, wiped his lips and pouring more of the cocktail into the glass, he smiled.

‘Old man, a slump is a downward trend, a fall in the market.

These people are saying that a huge fall in the market has hit our country.’ Mesoki raised his glass to his lips again.

‘Ha, ha, ha, a loss, ha, ha… ‘ Matele guffawed. He often said that his mind. became sharper every time he sat laughing and drinking with his friends.

‘Now you tell me, friends, for how long have you seen this slump?’ Matele questioned, as if asking himself. Then his eyes swelled up with a deep sadness, and he seemed like a bloated corpse floating on the surface of still waters.

‘Friends, our masters, the bwanas, say the slump has hit us today, but I have been seeing it coming for many years, from even before 1930. .While scrubbing the dirty utensils of a trader I used to wonder why my parents didn’t keep me with themselves in the village ‘

Translated By Chandana D1itta

Jambo Rafiqui

T

he story of this country begins with the railways. At the inception of the railways, this part of the Black Continent let out ·a cry like that of a new-born – one who is suddenly exposed to the unfamiliar glare of light. But then the cry of the new-born child is an indication of it being alive! That’s why instead of being wary, the railway employees bent their heads to read the lines on the face of this dear child of theirs. Looking at their eyes filled with love, the little one stopped crying, began to smile and then burst out laughing.

The English priest who stood next to the railway engineer sent out a prayer to Jesus Christ, and made the sign of the Holy Cross on his chest and patted the engineer’s back, ‘May the Son of God shower his blessings on this beautiful child, amen., ‘Kenya!, The railway engineer kissed the shining forehead of the new-born, twirled his blond, sharp moustaches and rose to uncork the mouth of a century-old bottle of whisky from Scotland.

‘Kenya!’ He raised his glass of whisky and in a tone full of cheer, he said, ‘Kenya!,

In response, scores of hands with whisky glasses leapt into the air. It seemed as though this auspicious moment, overcome with joy, had broken into a dance in sheer excitement.

A few yards away from their English bosses, the Indian coolies sat next to the railway line in small groups around the fires they had lit for themselves. Like their masters, they too were celebrating the occasion drinking home-brewed liquor, smoking bidis and fooling around. Perhaps their laughter belied what their eyes were seeing – the sad faces of their wives and kids, thousands of miles away. Disturbed by what they saw in their heads they drank more liquor and taking a long drag on their bidis, got lost in their thoughts of being back in Bombay. What would they buy for their people…fancy shoes Rambai would love; Jeeto will be happier with a dupatta of deeper red; and how handsome would Bashir look in his English hat!

‘Bashire!’

‘Abba!’

Overcome with emotion, the father and son clasped each other in a tight embrace, immense happiness flowing out in streams of tears, fountains of joy soaking their beating hearts.

‘Oye, Shafiq, whose thoughts are you lost in?’

Lal Singh too was lifting the deep red dupatta from Jeeto’s face. ‘Bhai, not a minute goes by when I don’t think of Jeeto. I came away just two months after our marriage.’

Sighing deeply, Lal Singh looked towards the sky full of smiling stars twinkling happily, and he wondered why everything beautiful was always far away. Then.it was as though he could. see his Jeeto amongst the brightest of stars, draped in the same deep red dupatta, embellished with designs woven with a golden thread.

‘Oye, Jeeto, listen to me.’

‘Go, go away!’

‘Ha..ha..ha..’ Still laughing, Lal Singh was startled to hear familiar noises around him, Again today?’

Watch out Shafiq bhai, black me·n are headed this way. . . chas1nga lion.’ Lal Singh then turned his face towards the Indian camp and hollered loudly, ‘Beware… lion… lio. .,

Before he could complete the word, , something heavy fell upon him from behind the bushes with the speed of lightning. Ano er deadly force held Shafiq in an iron-like grip. Both the lions started to bore holes in the sky with theit roaring. There was utter panic all around. In the meanwhile, a group of shrieking African men appeared from nowhere and descended upon the lions with their sharp-edged spears. Within minutes, with the volley of jabs in th e.ir bodies the tormented lions broke into loud bellows while dying a slow painful death.

Raising cries of victory, the Africans dug their spears through the bodies of the animals into the ground. Once the lions went cold, the Africans were ecstatic and danced around the dead bodies in a frenzy. Drawing his last breaths, Lal Singh gazed at the brightest shining star where Jeeto was beckoning to him, wrapped in. her deep red dupatta. In the few remaining breaths, groaning and teary-eyed, Shafiq was also kissing the face of his son Bashir.

The noise and commotion attracted the attention of a couple of Englishmen, who reached the spot holding their double barrel guns. The Africans cast a fleeting glance at them and continued with their celebration. The Indian coolies, who were preparing to shift Lal Singh and Shafiq to the Red Cross camp, abandoned the wounded men and stood aside with deference. .

‘Beautiful!’ exclaimed an Englishman, impressed by the sight of t4e jubilant primitives dancing. .

The other Englishman was thinking how pleased Lizzy would be if he were to send the hides of these lions to her in England. The third one read the mind of his mate and said, ‘If one were to even touch theii; prey, these wretched fellows will turn into one’s deadly enemy. Now see how the whole tribe will taste the raw flesh of these lions. The hides will be given to those who have played the most active role in the hunting and killing.’

‘Oh, look! Two Indian coolies are lying wounded here.’

‘Poor things!’

It was as though the speechless Indian coolies stood pleading fervently to their masters. They stammered, ‘These two are really poor, sahebji. Please save them somehow, sahebji.’

‘Take them to the Red Cross camp at once.’

As soon as they heard the order’s of the white masters, the Indian coolies turned their attention to the injured men.·

‘Don’t worry. Even if they die, their families will get a pension of ten shillings each every month.’

Then he turned to his fellowmen. ‘How servile these Indian coolies are! Loyal and servile.’

‘Yes. Just like my pet dog. But, in fact, their loyalty itself is ‘a validation of the efficacy of our system. When one is dependent on a competent system, initially he may grumble and make angry noises, but eventually loyalty becomes a habit with him.’

‘You are right there. I am certain that once our system starts to operate successfully here, our African friends will also give up their animal-like ways and become loyal on their own eventually.’ ‘Ha… ha… ha.’ The face of an amused Englishman narrowly escaped the sharp edge of the spear of a dancing African, and instead of being apologetic, the man continued with his dance with a couldn’t-care-less attitude.

‘Bloody barbarians!’ Absolutely livid, the Englishman was about to spring upon the African with his double barrel gun when his colleague quickly intervened. ‘Don’t be a fool, Albert. A minor slip-up on your part and we will have riots on our hands, and then after the bloodshed these men will abandon work and run away.’

Albert gnashed his teeth.

‘Ronny is right, Albert. We need these men for this extremely tough mission of ours. We still have to lay hundreds of miles Still gnashing his teeth; Albert poised his gun as if targeting something in space, and it appeared as if his ears were yearning to hear the sound of a gunshot.

The well-mannered Indian coolies gazed at the bloodstains left by Lal Singh and Shafiq as their tears flowed silently.

Dancing joyfully and 1 jumping around, the Africans continued their screaming and shouting, savouring the taste of the lion meat in their thoughts.

Albert continued to gnash his teeth.

‘Kenya!’ A short distance away;, swaying in .the wind, European tents seemed to be crying out loudly in unsteady, happy, drunken voices, ‘Kenya!’

When the railway line reached the dense forests of Voi from Mombasa, the headquarters issued an order that the line to Nairobi be completed quickly.

The treacherous, narrow winding route reached up to the height of 5;500 feet. The freely-roaming, menacing wild animals and the lurking fear of sudden attacks by the savage tribes added to the challenge. But according to the orders it was imperative that the work be completed without delay. In order to accomplish ·this, it was essential that more Africa labour be employed to assist the Indian coolies. Therefore, the officer-in-charge ordered that men from neighbouring tribes be persuaded to join the work force. Responsible African staff members were sent to the homes of the surrounding tribal areas with instructions that they should sweet talk the tribal chiefs by presenting them with English clothes and hunting knives on behalf of the brave English Saheb Bahadur. They were also to tell them that the saheb was desirous of their friendship and co, operation for die completion of the railway line.

The Saheb Bahadur’s African representatives organized a grand feast for the tribal chiefs, who came clad in English clothes gifted to them by the Saheb Bahadur. They enjoyed sweet buns that accompanied roasted meat of some well-fed lambs but when that did not satisfy their large appetites, the local chiefs helped themselves to half-cooked sheep legs from the fire and started to chomp and chew the meat stuck to the bones.

‘This chakula of the wazungu is delicious,’ said a tribal head patting a railway employee on his back, ‘and it even appears puffed up. But rafiqui, if truth be told, it doesn’t fill one’s belly. After wearing the wazungu’s … what was it again? Yes, coat… one feels tied down. Tell the wazungu not to get upset but, truly, all these things are absolutely worthless. There is great joy in wearing loose animal skin or just to be naked. Next time, don’t bother to bring this stuff, though the knives of the wazungu are excellent. Tell him he is welcome to send a hundred or more of these hunting knives.’

The tribal head sliced a whole lamb that was being grilled on a big log with the knife sent by the wazungu, then burst out into wild laughter, ‘This knife is a very useful thing – so easy to hold.and so sharp to chop something! Yes, rafiqui, next time be sure to bring some fifty odd knives like this one, ha…. ha ha.’

‘Sir, if you send your young men to work on the railway line, the wazungu will distribute lots of shillings to them.’

‘Hee…hee… hee… Shillings? What will we do with these useless pieces of yellow metal, rafiqui?’

There are various kinds of metals scattered all over our region. Tell your wazungu to help himself to any number and any type of metal he desires. I always maintain that you black youth of today have lost your minds, that you drive yourselves so hard the whole day chasing after these worthless, pieces of metal. Go mform your white men that all my young lads will present themselves early in the morning to help them. But rafiqui, would not desire any money. If your wazungu can send knives that would be good enough and if they do not do that… even that would be fine. The wazungu are our guest, and it is our duty to come to their aid.’

‘You are a very good man, baba,’ said a black representative of the Saheb Bahadur, ‘and our wazungu are really nice people. Let the railway line react Nairobi, the life of the black men will transform and improve tremendously. Trains will bring novelties from far off places.’

***

Listening intently to the voice of Nature, the railway line was moving forward.

Arre…hold on for a moment.’ Nature held the hand of the railway line gently and stopped it. ‘Do you see that herd of elephants? Let them go away first. These bloody animals are very cruel. If they get even a hint of your presence, they will go wild and start to trumpet in anger. They’ll dig up your work and throw you into the,air, smashing you into smithereens.’

‘Well done! The danger is over for now and you may move forward. But do it cautiously. The route ahead goes through tricky hills.. .. What happened? Tired? How come? You are made of iron, aren’t you? Never mind.. Come, I will carry you on my shoulders.’

Riding on the shoulders of Nature, the railway line began to cover the hilly distance to Nairobi. After a while, Nature came to a sudden halt upon hearing a heart-rending scream. A cheetah had trapped an African between its sharp paws, and its teeth were digging deep into his heart, boring a hole there.

‘A–aa–h!’ The African who had been singing just a few moments ago collapsed and his soul ran shrieking into the dense forest.

‘Bang… bang… ‘ Two bullets fired from the rifle of the English officer silenced the blood-licking cheetah for good.

The officer got himself photographed standing next to the carcasses of the cheetah and the African. This photograph will be published in the papers. Lal Singh and Shafiq’s photographs had also been printed in various newspapers and were seen by Jeeto, who then threw away her deep red dupatta; Bashir had cried till he could cry no more, and had driven himself into a state of frenzy. Looking at the soul of the dead African running through the forest, the bushes whispered to each other, ‘Now who will sing to us?’

Nature gave a pat to the railway line and said, ‘Don’t get nervous. Let’s move forward. Some sacrifice is inevitable when you take on mammoth tasks.’

The railway line placed her head on Nature’s breast and sobbed her heart out. Nature comforted her, wiped her tears and then, holding her fo;1ger, it moved forward. In order to keep the railway line’s sp t up, Nature narrated to her many lyrical stories of the moon and the stars but the line continued to cover the distance silently, like a petrified fairy bending her head over her grief-stricken heart. After having moved several miles forward, a range Qf mountains spread both its arms and blocked her path.

‘Ha… ha… ha… ‘ As though mocking the line by baring his long teeth, ‘Tell me, little one, how will you proceed now?’

‘Bang… bang… ‘ The dynamite jumped up and down, and blinded the mischievous eyes of the mountain.

‘Bang… bang… ‘ The mountain’s bod was split apart. When Nature witnessed her beloved mountain blasted to tiny fragments, her voice drowned in, a flood of tears, ‘Poor child of mine-this mountain stood here with such pride for thousands of years. Look despite having died, its two parts torn apart at the centre stand tall and regal. Your hard-hearted cruel men have brutally murdered my precious, child. I feel like tearing them all to pieces; ·and then strangle you before getting rid of you.’

Nature’s anger made the railway line tremble in fear.

‘But no,’ Nature took hold of herself and said, ‘I will lend my support to you. because I had promised to do that But listen, tell your men ·not to be so heartless .’. .

After moving ahead a little, Nature leapt to· stop the railway line. ‘Look, this is the breg ground of various types. of deadly snakes. Look again… how they have bored holes into the earth at various places to make homes for themselves. These creature& are , very treacherous. Take each step with caution… eyes alert and watchful… hold your breath.’

:Just a few more miles and we will be out of reach of these wretched creatures. Well done. Now you can speed up and reach Haathi River. Our destination is not far from here/ Nature pointed out.

At the thought of being close to the goal now, the railway line forgot her exhaustion. Tripping and stumbling, it hobbled through Haathi River to reach Nairobi amidst loud cheering. The whole of Nairobi stood there to receive her with arms wide open. People went berserk with excitement, and loud music welcomed her. Music made the railway line’s heart jump with joy. The top railway officials accompanied by other honourable citize s came forward to greet her.

From a distance, Nature watched the railway line meet her people. She slunk back silently and receded far back into the dense forest. ‘Kenya!’ Glasses full of old brewed whisky were raised in toast.

‘Kenya!’ The whole country reverberated with the echo.

The railway engines, newly imported from England, started to pull luxury carriages from Mombasa to Nairobi – similar to a victory march, introducing the dark regions to the new light of modernity. Distraught by the continued sound of chug-chug and the shrill, piercing whistles, Nature receded further back into the jungle. The jungle was cleared around the railway line, dreaded animals ran off miles away and soon many small villages mushroomed there. The government appointed chiefs in these settlements and issued instructions that they take care. of the problems of the black people. Indian traders set up all kinds of shops and since items of daily need could not be bought from them without cash, black settlers had no choice but to seek petty jobs under the supervision of the chiefs appointed by the wazungu.

To earn a living, some Africans became railway coolies. Some found jobs a-t Indian shops, others toiled as labourers in the newly set-up farms of European immigrants. Some others boarded trains to Mombasa or Nairobi, where they found jobs as peons in government offices or worked in factories owned by Ismailis and Gujaratis. There were others who found employment as houseboys in European homes, or boi(s) in Indian households, working for food and clothing, and a salary of five shillings per month. Those who found no work survived with the help of the people of their tribe as they ran around in search of work. When they got something to do, their hunger was quenched, or the likely employers.

Or they felt happy to be friends with those who had found employment. When even that did not work, they became petty thieves. A former thief who was nabbed while stealing and jailed had told them that it was fun to be in the prison of the wazungu. There you got jobs without having to run around looking for one, and the convenience of guo, chakul_a, jumba came along free.

‘What? Guo, chakula, and jumba free?’ Those who did not succeed in getting jobs outside became eager to get arrested for some minor theft. But when they were caught stealing by the owners and were abused and kicked out instead of being handed over to the police, they were actually frustrated and · envious of some lucky friend who had been put into a jail.

Gradually the phenomenon of the Indian coolies became a thing of the past. They and their sons turned successful businessmen; they became middle-rung, well-off government officers or skilled artisans. The vacancies left by Indians were swiftly filled up by Africans. Mwangi became another Lal Singh, and Matele, another Shafiq. Many Europeans • became farm owners after clearing beautiful forests. And with the help of cheap African labour, they were prosperous in no time while yet others got employment as top executives in government offices.

According to official reports, the economic condition of the Colony of Kenya slowly gained strength. News of the wealth of this colony drew in many European and Asian hopefuls for work. The government proceeded to prepare many schemes in accordance with modern trends in order to ensure habitation.

More and more jungles were being wiped out.A web of railway lines and highways was spreading all around the country.

Soon’ small shanty towns donned new robes and aspired the big cities. They swaggered about m their new finery while some forests dressed themselves up as small settlements.

The god Uranus of the Black Continent gracefully accepted his defeat and handed over his crown to the beautiful god of a new civilization, Jupiter.

Eventually, scarcity of jobs in smaller settlements drove the black people to big cities in large numbers. ‘When so many others have found a home there, we will also find a way to survive.’ The African parts of the cities start d to fill up. How was it possible to build so many schools to accommodate the children of such a large population? A lot of ·money had already been invested in building hospitals for the black, how could more be built? Thousands had already been given work and a few more could be accommodated, but it was not feasible to make adequate room for such a large multitude. Anyone and everyone was heading to the city.

‘Black people are so uncivilized.’

‘You better stay away. from the black – these people are infested with dangerous diseases.’

‘So many black people are sitting idle, bumming around. Why does the government not throw them into the prison?’

Many unemployed African youth would go off-track, and rolling out cigarette smoke from their nostrils, would roam the streets like habitual criminals. They moved around suspiciously, always on the lookout for an opportunity to make a quick buck. Some others would lose hope and return to their hometowns, only to come back to the city once again in search of work.

The colony continued to make progress. The new inhabitants became wealthier, and more and more Africans got employment for the completion of new projects. Large numbers of Africans kept pouring into the city, and many of them remained jobless.

Despite many schools, hospitals, and scholarships, Africans continued.to be sick, uncultured, and uncouth.

This was Nairobi – the heart of East Africa. Thousands listened to its music, swaying to its magical beat, and people across Europe and Asia tapped their feet to its rhythm. A network of smooth, tarmac roads was laid out everywhere and in place of people, one could see rows of cars racing up and down. In the middle, on many crossroads 1sat a whole lot of manicured green islands decked up with myriad fragrant African flowers These islands looked like dolled-up women winking, beckoning the motorists towards themselves. On both sides of the roads are shops built in Western style with modern corridors, through which walked young women wearing skirts of the latest fashion, hand-in-hand with their beaus. They would stand in front of a shop window and whisper, ‘How beautiful, darling Ledona!’

These were the corridors swept every evening by an African sweeper who would wonder – if I were to own one of these shops, how many shillings would I possess? These many! He would pause, put his hands together to form a cup and gaze at them as though looking at a pile of shillings there – no, these many! Then he’d spread his hands apart, open his arms and ponder… and then, as if hearing the jingle of the shillings slipping from the gaps between his fingers, he would bring his hands hack together and think – these many are enough.

Every year, by the side of these corridors, many skyscrapers rose . high. And with contempt, they recalled the city of Nairobi as it was fifty years ago. In these skyscrapers, there is a huge number of offices – including local agencies of many international airlines where passengers from far off countries are welcomed, and air tickets worth thousands of shillings are sold to passengers who go home on vacation. There are offices of goodwill missions of foreign countries that organize conferences to discuss ways to improve the lot of African people. There are offices of import and export companies that sell meat, butter, bread and other indigenously created marvels to other countries and import motorcars, good quality ready-to-wear garments, perfumes, electric cooking ranges, and refrigerators etc.

This is the largest bank of Nairobi where hundreds of employees and clients are engaged in exchange of money. At its door, is. a young man who is a matriculate standing in a dilemma, wondering whether to g-o in and inquire about his job application or to wait for another three or four days.

Here stands the bungalow of a very wealthy Asian, at whose gate a group of unemployed young Africans stand asking the mistress of the house, ‘Mama, need a boi for the house?’

‘Go, go away. There are already two such scoundrels in the house.?

Then there is this taxi driver rubbing his palms and humbly pleading to the master, ‘Forgive me this one time, saheb. Please don’t dismiss me. Give me one more chance.’ Standing near him is his African fellowman terribly anxious with the thought that he will not get the job if the master accepts the driver’s plea.

Shillings! Cents!

Hee..hee..·. hee… Shillings? What will we do with these useless pieces of yellow metal rafiqui? ‘We are sick.’

‘Go get shillings for the treatment – this 1s not a charitable hospital.’

‘We are starving.’

‘You don’t get food for free.’

‘Our children are running around uselessly.’

‘But where are the shillings to build more schools?’

Shillings! Cents! Nothing moves without these round pieces of yellow metal!

Nairobi!

Mombasa!

Nakuru! .

The Black Continent is ablaze with lights!

When one is dependent on a competent !)Stem, in the beginning he might grumble and make angry noises, eventual/y loyalty becomes a habit with him.

‘Why do you loiter around? If you wish to fill your belly, you have to work for it. Earn your shillings with some honest work.’

‘Work? Where is work?’

‘Look for work That itself is your work.’

Two trains halted at Voi Junction between Nairobi and Mombasa. ;Many years ago there were unpassable dense forests here, now there are crowds of people all around. One of these trains was headed to Nairobi from Mombasa, and the other to Mombasa from Nairobi. Two black men came out of the third class coaches of both the trains. Sad and worried, they both came and stood near the water tap on the platform. They washed their faces, drank some water and then looked at each other.

‘Jambo rafiqui.’

‘Jambo!’

‘Where are you going?’

‘Nairobi.’

‘Where have you come from?’

‘Mombasa.’

Here, have a cigarette, rafiqui’. Why are you going there?’

‘To look for work. Where are you headed rafiqui .

‘Mombasa.

‘Where have you come from?’

‘Nairobi.’

‘Why are you going there, rafiqui’.

‘To look for work.’

Translated by Usha Nagpaj‘

*******

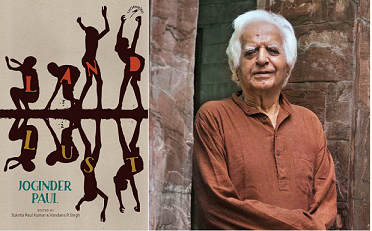

JOGINDER PAUL (1925-2016) eminent Urdu fiction writer was born in Sialkot (Pakistan) and migrated to India at the time of Partition, after which he lived in Kenya for a long time. He chose to write in Urdu, with a conviction that Urdu is 'not a language but a culture'. Though part of the Progressive Urdu Writers' Movement, his creative writing reflects a strong modern sensibility. Paul's fiction is widely read and is the recipient many literary awards including the SAARC Life Achievement Award, Iqbal Samman, Ghalib Award, the Urdu Academy Award and others. His fiction has been translated into many languages. His fiction in English translation has been published by Penguin, HarperCollins, National Book Trust, Katha and others. The well-known translations of his works into English are Sleepwalkers, The Dying Sun, Black Waters & Blind.

Leave a Reply