Tarun K. Saint with M.G. Vassanji

A Foreword

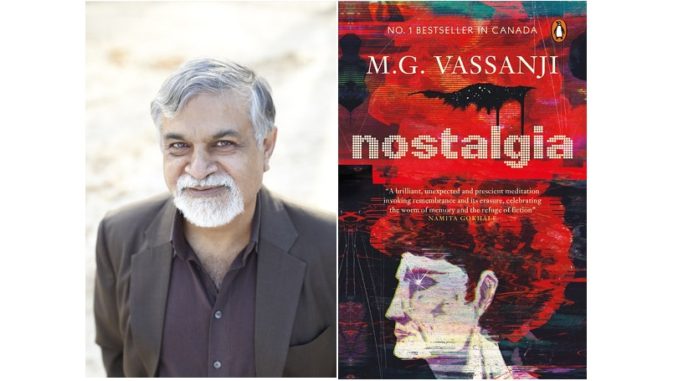

This session features MG Vassanji, who is well-known to writers and readers from South Asia and abroad. Brought up in East Africa, now based in Canada, he is a writer of literary and speculative fiction. The first chapter of his novel Nostalgia follows this dialogue.

**

Tarun K.Saint: Welcome to this session of South Asian SF Dialogues. You have written major novels drawing on your memory of growing up in East Africa, documenting the history of immigrants from India in Kenya, Zanzibar and Tanzania in fictional form and as memoir. A fresh perspective is achieved in your work via research into oral history and folklore. Have the themes of history, memory and identity been crucial to you from the outset as someone part of a community distanced from its roots?

M.G.Vassanji: Yes, it began when I arrived in Toronto after a two year postdoc and eight years in the US, at MIT and Penn. At university, I had done some research in recent African history and Indian (South Asian) involvement there. Africa was very close to me and so was my Indian Gujarati (Khoja) heritage. In Toronto I realized I might not be able to go home, and felt the urge to write stories to recreate the street in which I grew up. Uhuru Street. And I began a novel that was more historical and exploratory about Asians in East Africa. There was a lot of material, written by British administrators and the explorers—Burton, Speke, and so on. Whatever one thought of them, they did describe. Of course, I had my own memories, and the stories I grew up with. How that all came together is even now a wonder to me. You start with scraps and books, and then you have a novel.

TKS: Before turning to such themes as displacement and assimilation you completed a degree in nuclear physics. Was ‘hard’ SF written by authors such as Asimov, Clarke and later Larry Niven and David Brin (many physicists themselves) or for that matter astrophysicist Jayant Narlikar from India, part of the conversation at MIT and Pennsylvania, or even later?

MGV: I had seen and occasionally one or two books by Clarke, Asimov. I did not find them too interesting, I’m afraid. I found Fred Hoyle’s work more interesting. He was of course a real physicist. And Fahrenheit 451. In hard science fiction it seemed to me you could say anything. I am more interested in the human—the conflicts within, the joys and sorrows.

TKS: Which writers were key influences as you began writing and publishing? Were writers from the Anglo-European tradition more important, or was it the African greats like Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka and Ngugi, besides Naipaul and other writers of an Indian background? How did this hybrid set of influences shape your sensibility?

MGV: I wouldn’t say key influences, but those whose works inspired and encouraged me—the African writers you mention, yes. They did in their writings what had not been done before—put Africa on the literary world map. Ngugi especially, coming from Kenya and opening up the world of the Kikuyu people for us. I came from a world that did not exist in the world of fiction. I would say also Graham Greene and Joseph Conrad, with their outcasts and itinerants—people who belonged nowhere, really, and were closer to what I became. As an undergraduate in the US struggling with faith, Dostoyevsky and later Tolstoy. Midnight’s Children, of course.

TKS: After moving to Toronto you have continued to explore a diverse range of issues and concerns in your work, including the experience of double displacement. In your dystopian novel Nostalgia (2016), the theme of memory is explored in a futuristic setting, where aging is forestalled through memory implants, seemingly enabling immortality. The phenomenon of Leaked Memory Syndrome or Nostalgia observed by Dr. Frank Sina, in which memories of previous lives resurface, leads to many ethical dilemmas. Tell us about the genesis of this Toronto based thriller.

MGV: It emerged from the concept of assimilation. Immigrants are always told to assimilate. But what does that mean? You cannot simply discard your memories, language, and heritage, not to say your physical features. One evening, sitting on my porch, I mused, Wouldn’t it be nice to rid oneself of one’s baggage (the concept of baggage I explored in my novel, The Gunny Sack)—change physical features at will, rid oneself of memories and adopt new ones, as one goes on to live long enough.

TKS: Was there a conscious attempt to braid metaphysical conceits from Indian philosophy (reincarnation of the self/soul) explored earlier in Gothic style ghost stories like Madhumati (featuring the late Dilip Kumar and Vyjayanthimala, 1958) with contemporary ethical concerns stemming from genetic engineering?

MGV: They came naturally, and as inspirations as the novel grew and acquired texture. Indian metaphysics and folk mythology are part of my heritage. I grew up with the concept of “my previous life.” The idea of defeating or delaying death and changing personality raises several issues: who can afford to do it? The government can use it to try to rehabilitate criminals; it challenges the idea of karma—because you choose your new life; it challenges the concepts of sin, punishment, redemption; and of course it challenges the idea of a powerful God.

TKS: In the novel, access to memory replacement tech (‘rejuvenation’) is only affordable by the very rich. Please expand on your sense of a differentiated future to come, both within countries and across the digital divide globally (as William Gibson put it, the future is already here, only it is unevenly distributed).

MGV: The wealthy part of the world can afford to live longer with better lives and therefore it attracts immigrants and exiles, who have to be kept in their world—which is nice to visit for holidays but always out there. This of course happens even today.

TKS: The term Nostalgia (with its roots in the Greek term nostos, a word conjoining the notions of returning home with being in pain) is given a fresh connotation with medical overtones in your novel. Is there a sense of the intransigence of memory underlying this, a refusal to succumb to tech driven erasure of older forms of identity?

MGV: I just couldn’t avoid the idea that however much you try, you cannot get rid of memories—they’ll find ways to sneak in. A song line, a word heard somewhere, a scene from a movie can bring on an avalanche of memories.

TKS: Is it possible to write serious SF basing oneself in societies (or communities) which are fundamentally religious and superstitious? One can, of course, write SF as a dark satire about such communities in the manner of Swift’s Voyage to Laputa or, perhaps look back with nostalgia from a late 3045 BC about a distant past when Hanuman could fly and carry back a mountain for a magical herb (Incidentally, the Black Panther movies do something similar by imagining pre-colonial African with Shamans). Even a very brilliant novel like The Overstory, by Richard Powers, has difficulty with the Indian (Hindu, of course!) commuter geek in some future time who whines about Indian gods even as he creates complex modules. What kind of social structure did you imagine in your novel, Nostalgia?

MGV: I imagined a secular, professional elite without any religious beliefs. Then there are pockets of society that cling to religions that themselves have undergone transitions. The Black church on Walnut Street is a remnant of an old Christian faith. Then there is the religion park in the novel where religion is occasional—you can partake of any rite that suits you. Then there are the Indian and pseudo-Indian fanatics who burn themselves to death. All these are allowed to exist as long as they don’t violate the status quo. A bit like Cambridge, Mass in the early seventies!

TKS: One of the crucial problems that has troubled SF writers from the time of Frankenstein onwards is that of imagining human love (and sexuality) in future time. Human love is either monstrous or impossible. Think of Karl Capek’s RUR or Ishiguru’s Never Let Me Go, where love as a sentiment important for the survival of our future becomes unimaginable. In Chris Marker’s great film, La Jettee, the man trapped in a dark authoritarian future travels back in time only to realise heartrendingly that love is now only a fading memory. In Tarkovsky’s haunting version of Solaris, the protagonist understands that love in future time can only be the love for simulacra. To what extent did your speculations about future identity constructs encompass the realm of love/eroticism while writing Nostalgia or after?

MGV: I did not think I was writing Science Fiction. To me that is a construct where anything goes. I thought of myself as writing a realistic novel, very much set in our world, but dystopian. With humanity as I know it, but in altered circumstances. And so the novel was based on the life of a man, with a mother and father and sister. He may have fictional memories of them, but to him they are real. His feelings of empathy and sadness are real. His domestic and sexual life at home is a failure; that is partly a function of longevity and generational disparity. But there comes into his life the very sensual Indian woman to whom he is attracted. He is capable of love. And the fond memories of his real life in that other world that he left behind and calls him, with a wife, are also very real. And there is the lesbian relationship between two women that is described in the novel. It’s a world you can go to, and find things somewhat different.

TKS: Let us know a bit about work in progress, including your forthcoming books and stories. Will the dystopian thriller/SF/speculative fiction remain a possible mode of expression?

MGV: I have a completed novel about a physicist from present-day Pakistan. What I am writing now is a very speculative dystopian novel.

****

Nostalgia: M.G.Vassanji

ONE

His name was Presley Smith. It was the seventh or eighth time he’d had it, he told me. Each time this phenome non in his mind began with one persistent thought, a string of words that had no meaning for him. It’s midnight, the lion is out.

—And the rest of this condition? I asked him.—Any thoughts that follow? Pictures, images in the mind? They do come?

He waited, before responding,—Yes, they come scattered like . . . not always the same. I forget . . . A few times the red bumper of an antique car, and part of the fender. I don’t under stand them—and why this one thought like a prelude . . .

—Do you see these words or hear them?

A longish pause.—I don’t know. Hear them, I think.

—Any other phrase or words that follow these?

—No. Just this one.

—You know what it implies—this kind of recurring thought? You came to me, so you appreciate its significance.

He nodded, spoke slowly, uncertainly.—Something left over from a previous memory? A life I left behind a long time ago. But I can’t relate to this thought, this image. They are alien.

—That’s how they often come—you don’t understand them. And the trick then is not to try and understand them, unravel the thoughts—that only feeds the syndrome and revives those dead circuits in the brain—and brings more of them back. And you don’t want that.

—No.

I watched him stare away at the window behind me, losing himself; he uncrossed his legs, crossed them back again, returned his gaze to me. The window always had that effect on patients, drawing them out, calming them. On the moni tor, hidden from him, Presley’s pulse had already steadied.

I asked,—Do you see in your mind what might be a lion— out stalking, perhaps? Do you have an image of it?

—No.

—Not at all? . . . And midnight—do you see midnight, darkness?

He shook his head, repeated drily,—No.

He was listed as a patient who’d seen two doctors in the city in recent years. Once for a severe attack of Border flu, during the Outbreak three years ago. And then a year ago a consultation with an orthopaedist. I looked up from the monitor.

—Any physical symptoms—racing heart, sweating—to accompany this, er, phenomenon?

—No . . . But I’m not sure, Doctor.

—What?

—A couple of times I thought . . . burning . . . some smoke, meat. I’m not sure. It could be the new neighbours, they like to barbecue.

He grinned sheepishly. But now his pulse had gone up, the fear index risen. This was surprising, the first alarm bell. —And how exactly did it first appear, this thought about the lion out at midnight? Suddenly, full-fledged, or did it approach gradually, begin with a hint, sort of?

—The latter . . . I think . . . like an approaching some thing, it began with a feeling, an expectation, I think.

—A certain mood—that feeling?

He nodded quickly.

—A low mood?

—Yes.

Presley Smith had an Afro-head with red hair and pale skin; striking green eyes, planar nose, large ears. A well-done reconstruction job if somewhat eccentric. The average body frame was, I guessed, as before. He would not be an ethnic purist, or an idealist, I surmised from those eclectic features, not someone hung up on history and origins. And he would not be one of those religious fatalists for whom another, perfect life lies somewhere else, in abstraction, why not let this one fade away. A practical man, an everyman named after a twentieth-century pop icon. Then what ails him, I wondered, what demons from his previous life have come to prey upon him, and why? It’s a question we ask ourselves often enough. The answers rarely satisfy, the soft, slimy mass in the head that we call the brain still eludes us, as enigmatic as ever.

Leaked memory syndrome—Nostalgia, as commonly known—is a malady of the human condition in its present historic phase. Reminders of our discarded lives can not yet be completely blocked, but we can expect their intrusions into our conscious minds to diminish as our understanding of thought-complexes increases and our ability to control them improves.

Chemicals do alleviate the condition, but often they are blunt, their effects diffuse, with collateral outcomes to negoti ate. Stubborn cases require the more intrusive ministrations and shock tactics of a surgical team. It was too soon to suggest anything yet. Meanwhile a lifetime of experiences was ready to flood into his brain behind this lion-harbinger that was only a minor irritation now. Was he aware of the danger that lurked ahead, I could not help but wonder. But then that’s what we were there for, the nostalgia doctors, to close the gates behind the scouts and let the past remain hidden.

I noticed that his right knee, crossed over his left, would go off into a steady vibration that he struggled to bring under control, before it set off again. He could easily have had that seen to. On the vibrating leg, in the gap between his black shoes and green pants he revealed a garishly bright yellow sock that periodically flagged my attention. It is these little tics that often are a giveaway, signals from the land of the dead.

They’re all a puzzle, each stray and escaped thought is only the barest tip of a universe that lies beneath. How far do you reach inside to stem the leak? The deeper you dig, the greater the chance of falling into an endless pit—a hazard ous operation. It needs a delicate hand to know when to seal off and withdraw; turn off the lights and go home and hope there’s no repair needed in the foreseeable future.

—Have you had previous consultations of this sort? Treatments?

He should not remember them if he had them, and he didn’t.

I prescribed a tranquilizer, and a monitor patch for the arm. If he had an episode, there was a means to signal it, he should on no account dwell on it. We settled for a meeting the following week. I have preferred personal meetings at the beginning of consultations, because with the actual talking person before me, tics and all, I can begin to form my clues about the intruders lurking behind their minds. It is easy and amusing to picture them as so many worms to be captured and put away.

—If it worsens before then—this condition—let me know.

—I will. Thanks, Doc.

—Don’t be shy, now.

—I won’t, Doc. Thanks.

He looked surprised at my concern for him, and I felt a blush of embarrassment. We shook hands, and I watched him leave. He had a sturdy profile, with a swaggering walk that did not fit what I had seen of his personality. I kept staring after him, until the clinic manager Lamar’s ample frame filled the doorway suddenly and broke my trance.

—What’s up, Doc?

—Something about this case.

—Oh? What?

I shook my head and sat down.—Let’s see where it goes.

He looked disappointed, reminded me to look at a few reports he’d completed, and left.

From as long back as we can imagine, we humans have striven for immortality. Now that, in our rough and ready way, we’ve begun to approach it, we face the problem of what to do with the vast amount of information we carry. Even if the brain allowed such storage capacity, who would want to be burdened by quantities of redundant, interfering memories? Painful and messy ones? Therefore as regeneration techniques advanced to allow the body to last longer, mind renewal grew alongside. The term is colloquial and inaccurate, of course—what is a mind, after all? No matter, as someone quipped. In fact, it’s selected portions of long-term memory that we renew. New memories in new bodies. New lives. That’s the ideal, though we are still far from it. The body may creak and wobble; memory develop a crack or hole. In the leaked memory syndrome, or Nostalgia, thoughts burrow from a previous life into the conscious mind, threatening to pull the sufferer into an internal abyss.

I am myself a GN, a new-generation person—and feel the body-age sometimes, in the nuts and bolts, as it were, the connections and interphases. By law, no record of a person’s past life exists, nor of calendar age, but the body knows. I am old, in the original sense, though the word hardly gets used these days. Surely there’s a little truth to the media hype that we’ve attained the status of ageless gods. A flawed immortality, but we are the fortunate ones, a new species in the making, who’ve defied death. Very nearly.

Our triumph comes, naturally, with its problems. We’ve not created Utopia, perhaps never will. But the problems are old wine in new bottles, we’ve had them always. The war of the generations, as popularly called, or more plainly, the young versus the old, shows no signs of abating; mostly it’s a cold war, manifest in constant disgruntlement. There’s the occasional street riot that vents frustration. The GN-serial rampage two years ago was a terrible exception—eight elderly GNs murdered over a period of twelve months, their bodies savagely mutilated. The young G0 criminals were apprehended and dealt with. We have assurances from authorities that such acts are very unlikely in the future. We’re not rid of fanatics either—those who will cling to outdated ethnic identities that most of us have forgotten, or for whom longevity is philosophically or morally repugnant. The wide eyed few who dare to turn off their lights, turn down this gift that we’ve given ourselves. But progress is forward, we cannot go back.

At day’s end I came out of the Sunflower Centre into a world of cheery autumn brightness, the courtyard flush in the clear light of a low sun. Further up, the Humber ran placidly along its course down to the lake, and two crews rowed their boats one behind the other, in no great hurry. Across the river, the yellow leaves of October had been set coolly ablaze. It’s always a breathtaking sight. On the bank, this side, students sat stretched out, some with their book pads open, others strolling or hurrying along the paved path, making way for the odd bicycle or two.

I arrived at the riverbank and sat down on a bench.

There was a message from Joanie; she would be out that night at a hockey game with a friend. The Friend, I had every reason to surmise. I never cared for the sport, and was teased for it: Who was I, really? Meaning, what was I before I became what I was. I am, was always my answer. It was my creed, as a minder of memories. I didn’t care for the befores. But Joanie is a G0, a BabyGen, and Babies have no previous lives, no befores. They have actually been born—to be beautiful: flawless, symmetrical, smooth. She was visiting a neighbour and during a block barbecue joined me with a beer and seduced me with her banter. We dated hesitantly, then more passionately, and cohabited. But my beautiful BabyGen was now seeing someone else on the side. Who else but another Baby this time, it always comes to that, doesn’t it. And I no longer wondered what she saw in me.

I popped a couple of pills into my mouth, looked around me; eyes lingered a little too long over a couple of youngsters necking.

The problem with staring at beautiful youngsters is that you are caught between the lust for the pure and supple beauty of youth (I did have Joanie) and a desire for children of your own. I didn’t have children; if I did, in another life that had been erased, I didn’t know. But this man from Yukon, Dr Frank Sina, had none and longed for one. Why the persistent need, like a thirst when you wake up, for a child of your own? There are areas of the brain that conspire to create longings that should have been buried and gone. No amount of erasure and implantation can create musicians or artists at will. Or take away the need for a child.

But what of Presley Smith? He looked surprisingly youthful and limber—and yet his record showed a GN, like me. Evidently I have been negligent, not paid heed to those keep fit reminders we now find everywhere—and so I complain of malfunctions.

It’s midnight, the lion is out. A chant carried over from the past? A line from a poem?

Have I ever had stray thoughts that needed fixing? I cannot know, of course. But judging by my comfort with myself, I can only conclude that whoever my doctors were, they had done a perfect job sealing my previous life off. There was a short period in the past, however, when, very foolishly, though for the sake of research, as I explained to myself, I would lie in bed looking up at the ceiling and fish for a thought; when a likely candidate came I would detain it by repeating it over and over. It never lasted. Soon enough and mercifully I realized my folly and stopped fishing. Now as I sat meditating before the quietly flowing river bathed in the soft afternoon sunlight, I realized that I had a thought that would not go away, and it was precisely this: the image and words of Presley Smith.

*******

Notes Tarun K. Saint acknowledges the help of Dr. Alok Bhalla in framing the questions Excerpt from Nostalgia published with permission from Penguin Random House India.’ M.G. VASSANJI is the author of six novels, two collections of short stories and two works of nonfiction. His first novel, The Gunny Sack, was the winner of the Commonwealth Prize for Canada and the Caribbean. He has won the Giller Prize for both The Book of Secrets and The In-Between World of Vikram Lall, and the Governor General's Literary Award for Non-Fiction for A Place Within: Rediscovering India. His novel The Assassin's Song was shortlisted for both the Scotiabank Giller Prize and the Governor General's Literary Award for Fiction. He was born in Kenya and raised in Tanzania, and attended university in the United States. He lives in Toronto with his wife and two sons.

Tarun K. Saint is the author of Witnessing Partition: Memory, History, Fiction (2010, 2nd. ed. 2020). He edited Bruised Memories: Communal Violence and the Writer (2002) and co-edited (with Ravikant) Translating Partition (2001). He also co-edited Looking Back: India’s Partition, 70 Years On in 2017 with Rakhshanda Jalil and Debjani Sengupta. Recently, he edited The Gollancz Book of South Asian Science Fiction (2019). The bilingual (Indian-Italian) SF anthology Avatar: Indian Science Fiction, co-eds. Francesco Verso and Saint, appeared in January 2020. The Gollancz Book of South Asian Science Fiction volume 2 will appear this year.

Leave a Reply