Tarun K. Saint with Bina Shah

A foreword

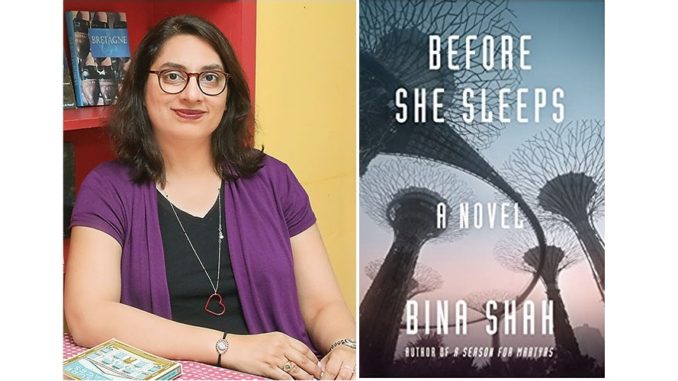

Each episode of South Asian SF Dialogues series will include a well-known writer in an exchange of ideas about the field, and the writer’s work in particular. This inaugural session features Bina Shah, writer of literary and speculative fiction based in Karachi. Followed with an extract from her novel Before She Sleeps

**

Tarun K.Saint: Welcome to this inaugural session of South Asian SF Dialogues, Bina. Fantasy literature has a longstanding provenance in Persian and Urdu-speaking cultures, with the Dastan-e-Amir Hamza being one example that has stood the test of time. To what extent has the advent of modernity in the wake of colonialism and the critical reception of Western forms enabled the advent of forms like SF/speculative fiction in this region? .

Bina Shah: There are at least three generations of Pakistanis who read the great works of classic science fiction by authors like Huxley, Asimov, Le Guin, Bradbury, Vonnegut and the immensely popular novels of Herbert, Gibson, Atwood in their youth. Now these Pakistanis are writing their own science fiction and fantasy, informed as much by the classics of the Western canon as by the Persian and Urdu influences. It’s pure creativity and artistry as opposed to a political or ideological statement in a genre that they simply adore for its openness and potential as opposed to standard literary fiction.

I suppose you can draw parallels between colonialism on earth and space colonies and resource theft in many works of science fiction, but I see that happening more in Afrofuturism than in Pakistan or South Asian SF.

TKS: In the subcontinent, SF writing in Bengali and other languages tended to be regarded as a branch of children’s literature, as a way of promoting science education. Has a more sophisticated form of ‘literary’ SFF drawing on fantistika and the irreal emerged in recent times in contemporary Pakistan, especially with the advent of the Salam awards?

BS: Science fiction and fantasy has been bubbling away in the country for at least the last fifteen or so years, but there are very few practitioners of it that we know of. Pakistani writer and translator Musharraf Ali Farooqi translated Dastaan-e-Amir Hamza in 2007 and Hoshruba’s first volume in 2009, and published his own Jinn Darazgosh in 2009. Meanwhile, Usman T. Malik, who just published his first collection of short stories Midnight Doorways in 2021, has been writing speculative fiction since 2003. The Light Blue Jumper by Sidra Sheikh was published in 2017. The Salam Award is intended to promote what they call “imaginative fiction” which encompasses science fiction and other associated genres, but it’s only been around for four years. It’s all very new and exciting at the moment.

TKS: Who were the key authors that influenced you as an upcoming writer? Let us take a step back to the time when you began writing as a novelist in the making. Were writers in the Anglo-American tradition a more significant influence or was it writing in Urdu and English like Manto, Khadija Mastur and Sidhwa? Can one speak of a hybridizing of varied influences?

BS: Bapsi Sidhwa was a huge influence on my writing. I read The Bride (published abroad as The Pakistani Bride) when I was a young girl and it left me breathless. It was all about character and plot, set in our own Pakistan, but in the mountains, which to me as a southerner living on the Arabian Sea was very exotic. She was also the first Pakistani author who captured my imagination as I’d grown up reading purely American and British literature. I only came across Manto when I was in my late 20s; I wouldn’t have been mature enough to appreciate him before that. But reading Manto then made me aware of the political dimensions of Pakistani writing, while Bapsi Sidhwa made me aware of its sociological context. Bapsi is very good at that, picking out the sociology of the nation but making it come alive in fiction format.

TKS: Your columns and journalistic writing provide an avenue for a critical intervention in ongoing public affairs, from a distinctive feminist perspective. Is there an intersection point for you between column-writing and fiction, especially in terms of theme?

BS: What I work on in a column will always be echoed in something fictional. I like to get at themes from both angles in this way. Writing about a social issue, or something having to do with women in a column or critical essay satisfies me academically and intellectually, but it isn’t until I write about it in fiction that I’m satisfied artistically. There are two parts to being a writer: the intellect and the soul, and I’m only happy when I’ve touched on a theme in both ways.

TKS: The feminist dystopia Before She Sleeps (2018) has been well-received. What led to this foray into world building and SF style extrapolation from contemporary trends, as an authoritarian futurist state in the Middle East seeks to control women’s reproductive abilities?

BS: A long time ago I was thinking about the idea of women who were there to be emotionally but not sexually involved with men who would pay for the privilege. But why would they pay for that privilege? Only in a world where that kind of company and comfort was in short supply. That’s sort of the process that I can remember germinating the book, and it began back in 2008 or so. At the same time I was thinking about the inferior status of women in our part of the world — the Middle East and South Asia — and envisioning a world in which there simply were no women. We were hated so much that we were somehow annihilated, erased from existence. I put the two threads together and came up with the book. It’s a bit of a Frankenstein, really.

TKS: This novel was praised by Margaret Atwood, whose The Handmaid’s Tale is a landmark in this regard. Did you consciously enter into a dialogic engagement with Atwood’s narrative in your projection of the culmination of tendencies towards religious orthodoxy and conservatism in an Eastern context?

BS: Not consciously at all, no. The comparison was drawn after the book was published because it came out when the television show on Hulu was extremely popular. If anything, I turned away from The Handmaid’s Tale because it didn’t speak to my experience growing up and living in South Asia. I needed to write something that spoke to me and to women like me who had experienced the same restrictions in our own cultural context: veiling, seclusion, polygamy, in both Islamic and Hindu traditions, in South Asian and Middle Eastern cultures. That’s why the book has characters called Sabine, Rupa, Diyah, Lin, and so on. We need to see ourselves in the art we create for ourselves.

TKS: Will the SF element be more pronounced in the books to come, in the spectrum from ‘pure’ fantasy to hard SF?

BS: I’m working on the sequel to Before She Sleeps, which will continue in the same vein of speculative fiction. But I’ve also written a short story for a special issue of Wasafiri, the magazine of international contemporary writing, called ‘The Book Smuggler’, about an exiled Arab prince on a space station. Part of his punishment is that he is not permitted to read books. So one of the staff members on the space station smuggles books from his father’s own library back on earth to the exiled prince. I never thought I’d write a story set in space, but there you go.

TKS: Your forthcoming story ‘Looney ka Tabadla’ dedicated to Sa’adat Hasan Manto brings in an element of black comedy in its depiction of a future South Asia where the media honchos responsible for the fanning of hatred in the region are finally held to account. Give us a sense of the genesis of this SFF reinvention of the metaphor of madness.

BS: I’d rather let the story speak for itself but I will say that this is a tongue in cheek play on the utopia that we often think will result if by some miracle Pakistan and India become peaceful neighbors and allies. I think I’m making the point that while Manto said it was madness that drove our countries apart, it will be madness that brings our countries together again. Maybe I’m saying it’s a pipe dream; maybe I’m saying that we’re all lunatics just by virtue of being desi. You can make up your own mind what the story means! I was just being playful, that’s all, and making fun of the macho men we have on both sides of the border who profit from our enmity thanks to an insane media machine. Plenty of madness all around.

TKS: Has the pandemic changed the ground rules for writers of SFF/speculative fiction, also given the radical reshaping of the normal and concomitant rise of authoritarianism in third world spaces?

BS: The thing about SFF and speculative fiction as I understand it, because I’m a very new practitioner, is that there are no rules. You make up the rules as you go along. Don’t like gravity? Invent a planet where there isn’t any. Don’t like misogyny? Invent a country where women rule, as in Begum Rokeya’s seminal work Sultana’s Dream/Ladyland. At the same time, the pandemic is fertile ground for all sorts of fiction that addresses viruses and pandemics, the wiping out of the human species and the resultant dystopia, climate change, medical advances and technology, and more. We’re seeing dystopia before our eyes with lockdowns and border controls, vaccine passports, and mRNA vaccines. Art is freedom, the freedom to imagine new worlds. That’s why authoritarian governments always try to clamp down on art, jail writers and poets, and ban books.

TKS: Can SFF/speculative fiction in its oblique, often estranged treatment of issues play a significant role in spaces where both formal and informal censorship hamstrings writers?

BS: The most famous treatment of censorship was in George Orwell’s dystopia 1984, where he wrote about a totalitarian government that ruled Britain and censored everything. So science fiction and related genres can actually take censorship and authoritarianism on directly. Another more recent example is the success of the Hunger Games novels, also about an authoritarian government and a rebellion against it led by Katniss Everdeen. Censorship has been imposed on science fiction, though, for example in China: apparently in 2011 there was a ban on portraying time travel in tv shows and movies because it “disrespected history”. Further back: after WWII, American occupation in Japan meant you couldn’t write about the war or mention the atomic bomb, but Japanese science fiction writers got away with it. When Ursula K. LeGuin won the National Book Award in 2014, her speech included the following quote:

“Hard times are coming, when we’ll be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now, can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine real grounds for hope. We’ll need writers who can remember freedom—poets, visionaries—realists of a larger reality.”

****

Before She Sleeps; Bina Shah

Chapter 1

SABINE

I MAKE IT A RULE TO ALWAYS LEAVE THE CLIENT’S HOUSE IN THE darkest part of the morning, the half hour before dawn, when the night’s at its thickest and the Agency officers are at their slowest. This is the time of day I fear the most, out of all the hours in the day that pass me by like flies crawling in front of my face. The Client, a man whom I only know as Joseph – none of us uses last names in this business – nods impatiently at all the rules as I set them down; he’s done this many times before, and not always with me. To my relief, he behaves himself, wrapping his arms around me and contentedly sighing every few moments, not attempting anything more intrusive than those chaste embraces.

Within a half hour, I can tell by his regular breathing that he’s fallen asleep. I never sleep when I’m with a Client. Insomnia is a lifetime’s curse without a night’s reprieve, even though it’s precisely what makes me so good at what I do. I slip away from the bed, find the armchair in the room and sink down in it. I match my breathing to mimic Joseph’s as he shifts from left to right and back again. Normally I don’t think, or daydream; I just sit there waiting for morning, knowing that the slightest tension in my body would be enough to wake him from his slumber. I don’t want that.

But towards the early morning, when the alarm on my wrist begins to glow, and I come close for a last embrace, Joseph tightens his arms around me again.

Although it’s not allowed, sometimes I bend the rules and allow a Client a moment or two of comfort before extricating myself gracefully and heading for the door. Lin always tells us to be wary about who plays by the rules and who pushes the boundaries. Joseph’s expensive watch on the nightstand, his plush bedroom slippers by the door, the black silk sheets on the bed, and the low glowing lights sunk into recesses at regular intervals across the floor, making a chiaroscuro of the ceiling, all tell me that this is a man to push boundaries wherever he can.

‘Joseph, I’ve had a lovely time with you. But now I have to leave.’ I turn around to smile at him, the smile that manages to smooth things over with anyone. I’ve spent hours staring into the mirror, perfecting that smile. It doesn’t come naturally.

Joseph raises himself up on one arm. His body was once powerful but now it’s on its way to fast decline: heavy, untoned shoulders, a neck that wrinkles and crepes around his throat, white hairs outnumbering the black ones still dotting his chest. ‘Stay. I can afford to keep you all day if that’s what you want.’

I grimace, my back to him. ‘I’m sorry, Joseph. The rules are the rules. I have to be out of here before dawn.’

‘But why?’

‘You know why,’ I say, momentarily nonplussed. We all know what’s at stake if we’re caught: the Agency has made sure to publicize all crimes well in the Flashes on the display, the Bulletins, even through door-to-door visits, something almost unheard of in this time where almost everything is done remotely and anonymously. All the more ominous when an Agency car is parked outside someone’s house and two officers, with their immaculate uniforms and unreadable faces, are educating someone inside about the repercussions of associating with illegals like me.

Joseph rests his hand lightly on my forearm. ‘I know people. Nothing is going to happen to you or me. If you knew who I am – ’

‘It’s too dangerous for me to know who you are. Or for me to stay any longer than necessary. Now would you please let me get dressed?’

Joseph sighs. But he doesn’t give up. He follows me to the bathroom, standing in the doorway, turning his head away as I coat my skin in gold silicon powder, then put on my clothes. He studies my face as I cover my body with as much cloth in as little time as possible. He follows me to the door of his apartment, his forefinger lingering on the security button, circling it, taunting me with his nonchalance. ‘Are you sure you’re not going to change your mind?’

The sun’s starting to rise, the sky shifting from black to smoky grey. In a few more minutes the blanket of night will start to lift from the horizon and the next Agency patrol will be on the street. Our cars are programmed to keep a two-hundred-yard distance from the patrols, and to abort the pickup if a patrol is on the same street as a Client’s house. My car will simply never arrive. Stranded, I’ll be spotted and my presence immediately messaged to the officers. I’ll be arrested and taken in and my life, as I know it, will be over.

‘Joseph, let me go. Please.’

My fear is an animal I can’t hide – I’ve never been able to completely control my expressions – but for some reason my vulnerability assuages something in Joseph.

‘All right. But keep a night free for me sometime next week.’ I nod, wishing I never had to see Joseph again. His eyes search mine for some sign of disappointment that I have to leave. My gaze is fixed steady on him, and his finger depresses the security button. The door slides open silently. I step out, exchanging the calculated danger of his apartment, and the greed that furnishes it, for the open territory of the illegal and the hunted. I move down the stairs, pause, then creep to the doorway of the luxury apartment building where Joseph lives. My footsteps echo like gunshots in the giant marble-floored hall.

The robotic doorman hums quietly at the left of the entrance. It’s just a computerized desk, where residents punch in for security and to collect messages, or to leave their own messages to complain about a malfunctioning cooling unit or request an extra display to be installed in the second bedroom, but Joseph likes to pretend it’s human, and makes fun of it for being stupid.

I’m grateful for the desk’s stupidity. The gold powder that I’m coated in will prevent the security systems from picking up my DNA on the scanners. The video camera won’t get activated and I can’t be identified as I walk into or out of any building in Green City. As for the other humans: most of the residents are asleep this early in the day. If anyone does see me, they’ll keep their head down and pretend they can’t see me either, like the doorman. No matter how many good-citizenship sessions they attend, now matter how much of the Handbook they’ve memorized, nobody really wants to report me – the filling out of voluminous forms, the interrogations; it’s just not worth the trouble.

My eyes scan the road for the unmarked car, and with a spasm of horror I see a dark blue Agency car with hologram plates sliding down the street toward the building. My heart starts to pound. I pull my head back in. For a moment I’m afraid I’m going to lose all sense of reality. I tremble as I stand in the doorway, counting slowly backward from a hundred.

The Agency car stops directly opposite Joseph’s building. I flatten myself against the wall as the two officers emerge and stand at the side of the road. I’m ready to run back to Joseph’s apartment and beg for his protection. My own car will have sensed the Agency car and gone straight back to the Panah. My only hope is Joseph’s generosity.

If the officers come into the building, they’ll easily see me from across the hall with its cavernous ceiling and absence of greenery; the large hall is as open as an airplane hangar. I might be able to duck down behind the doorman and crouch into the space beneath the counter. If they only glance into the hallway to look for suspicious activity, there’s a chance they won’t catch me. They might be tired, their senses and instincts not working at their best. They will conduct only a perfunctory search, and I can hide, then signal for a new pickup from a different location.

My body lowers, instinctively assuming the stance of a sprinter. I’m a good short-distance runner, but I lack the stamina to go long distances. A sudden burst of energy is all I need now to get under the desk. In my peripheral vision I can see the officers kneeling down, examining the ground for traces of something. I hate the very sight of them, their close-cropped heads and their authoritative, well-developed shoulders. Why have they sent Officers to do what a security squad could take care of? Where’s their electronic equipment, the sniffer bots, the handheld scanners that can trace a drop of blood in a ton of dust?

One of the officers shouts out to the other, and reaches out in front of him to pick up something small that glints and sparkles in the morning sun. I realize that this is no murder investigation. It’s not even a sweep for illegals. The officers don’t look like they are on active Agency duty. They’ve spotted something valuable that someone dropped as they walked by – a gemstone, perhaps, or a currency stick. They’re not exercising their official powers. It’s good old-fashioned greed that’s made them stop, get out of their car, and acquire the trinket to keep it for themselves. I almost laugh out loud in relief.

They get back in their car and drive away. I bend over, trying to regain my calm. My mouth tastes bitter and I reach into my purse for a mint strip that contains a small calming agent embedded in the freshness crystals. My skyrocketing pulse immediately comes back down to earth. As I stand up, the unmarked black car sweeps in to pause in front of the building.

The Panah is waiting for me.

I slip inside the car. The doors lock automatically and the car glides away from the pavement, a big black swan that folds its wings around me and carries me back to the Panah. Embraced by the warmth of the heating and enveloped in the softness of the leather seats, I allow myself to close my eyes. I never have to worry about the Agency officers when I’m inside; they have their instructions never to stop a car with darkened windows or the special silver detailing on the back, which triggers a DO NOT OBSTRUCT message to their handheld devices as we pass them by. I usually never speak to the driver, but right now I have a desperate need for friendly contact. ‘What happened? Did you see them?’

‘Good morning,’ the driver replies at last. Well, he’s not really a human, just a computerized voice and chip system, behind a customized panel, since this is a self-driving car. That keeps all of us safe, in case someone stops the car when it’s on its way to me. It can’t talk much beyond its basic command set, and it’s been programmed to emit false destination signals to Agency officers. ‘My system detected a potential threat,’ continues the driver, ‘but threat level is now low and I am authorized to continue your ride.’

My fingers reach for the flask of tea that Lin always puts in the car. The physical manifestation of her warmth and her care takes the edge off my exhaustion at the end of a long working night. I take a few grateful swallows, then sink back against the seat and close my eyes for a moment.

I want only to see darkness, but instead, my mind conjures up the image that Rupa, Lin, and I saw on this morning’s info bulletin: a dead woman, lying on the floor of a nondescript house somewhere in Green City, her body picked out from the shadows by a ray of bright, unforgiving sunshine.

The info bulletin’s quick, urgent female voice issued from the display, a large screen on a low table in the middle of the Panah’s biggest room. ‘It is reported today, I repeat, today that a Wife has committed suicide in her home in Qanna neighborhood. She was found by her third Husband, who reported the event to the Agency. The Agency immediately sealed off the area, but our sources tell us that the Wife committed suicide in a most criminal manner.’

My stomach clenched at the sight of the woman, arms and legs splayed in grotesque angles, blood pooling around her body, trapping her like an insect in a circle of red amber. Rupa clutched my arm, Lin stiffened by my side. They knew how difficult it was for me to hear this kind of news.

The tinny, officious voice went on, each word a hammer to our hearts. ‘Nurya Salem had five Husbands and was due to be married again to a sixth at the end of the month. It is suspected that she was opposed to the marriage, although this cannot be confirmed. Her children, five girls and two boys, have not been told about her actions. They will be taken to a care facility, informed of their mother’s death and treated for trauma before being returned to the house where the Wife lived with her Husbands. This particular family will be reassigned a Wife by the end of the month, along with compensation for the tragedy endured by them, by order of the Perpetuation Bureau.’

Diyah was saying a prayer in the corner of the room as Lin switched off the display. Even Rupa bowed her head, watching me from the corner of her eye to make sure I was all right. There were no whispered prayers on my lips. Why should I weep for them?

The picture of a tree-filled settlement, green leaves skittering in a gentle breeze, now filled the display, to calm and soothe us. But the woman’s corpse still lay heavy on our minds, her blood smearing us with complicity and despair. It’s understood that while the Officials try to make life in Green City look smooth and placid, sometimes violence or lust or greed breaks through the artificial calm. Crime illustrates what we humans are fully capable of when our manmade defences against our lower selves prove too much to bear. They’ll even use suicide to their advantage. By showing us the woman’s body in such a cruel way, the Bureau wants us to see what happens when human nature isn’t contained. It wants us to know we aren’t strong enough to contain it by ourselves. That we need their help, their guidance. Otherwise, we’re lost. However, we are not Wives, because we aren’t of Green City: we do not consent to their conspiracy, first to decimate us, then to distribute those of us who remain among themselves as if we were cattle, or food.

When I open my eyes again, we’re already far away from Joseph’s compound, sailing swiftly for home. I watch the growing dawn through the darkened windows of my car. The sun has vaulted past the horizon now, the city’s ambitious skyline shot through with threads of a lighter grey. The edges and spaces between the skyscrapers are already starting to bleed red. But the city isn’t singing yet. On a busy day, with its myriad radio frequencies and optic lines, the buzzing of the high-efficiency cars cutting smoothly across fibreglass roads and planes vibrating through the sky, Green City is a chorus of sound and sight. Only the crackle of neon punctuates the hush in those last ghostly minutes when night fades and gives way to a new day in Green City. When I come out of my underground life to the surface, my eyes are weak as a mole’s. I’m dazzled by all the sunlight, limitless space: infinite possibility.

It’s hard to believe that only a hundred years ago there was nothing here but sand. Can you imagine a city pushing itself out of the ground, a nation giving birth to itself? First modest houses, low walls, long, dusty roads, the infant city encircled by desert, reminding it of where it came from. Then more ambitious buildings, bigger houses, children overtaking their fathers, suburban settlements cratered far and wide, pushing the desert back further and further. And now the desert is a mirage where our ancestors once lived. We have defeated the desert and replaced it with this paean to human achievement.

This city, among whose numbers I used to count myself, was once known as Mazun, an ancient name meaning ‘clouds laden with rain’, even though deserts rarely see rain. The heat used to be unbearable every day of the year, and most summer nights you felt as though you couldn’t breathe when you stepped outside. So the Leaders ordered the planting of thousands of trees and cared for them as if they were made of gold. ‘Plant Your Future’, the scheme was called. They requisitioned millions of gallons of cultivated water so that the trees would grow faster than normal, and in twenty years dry desert gave way to lushness and fertility. Seduced by such beauty, the clouds massed over the city, but still needed coaxing to release their treasure. The scientists seed them regularly with biospores whenever they need rain, some of which is falling now on the wide boulevard, misting the windows of the car.

This is how Mazun came to be known as Green City. The Leaders didn’t mind; in fact, they encouraged the new name, knowing everyone would feel prosperous and content as the citizens of a green and pleasant land. They wanted to sever the ties with the past, and to be known as the creators of this oasis, powerful deities who could change even the weather through their will. The Green City ecosystem, a trademarked brand, is all about preserving the seasons and cycles, or at least the illusion of them.

But we have had to pay a heavy price for this new version of normality.

Sipping Lin’s tea, speeding safely away from Joseph’s building, at certain moments in the back of this cold steel carriage, my femininity is no longer my weakness. Then again, women like me are never meant to feel safe. We steal our freedom when and where we can. And I, the provider of peaceful sleep to these men who pay for something they can never own, am destined to spend yet another sleepless night in my bed at the Panah. I never sleep; I keep vigil over my Clients, the men, while they dream. I give them protection and shelter against their nightmares, their loneliness, their melancholy. I’m their sentinel, and in return they pretend to the authorities that I don’t exist. Because if the authorities knew about me, or the Panah, we would die.

I am Morpheus, Insomnia is my ever-faithful lover. Maybe we’re crazy, or we’re criminals, like wretched Nurya Salem. But we know exactly what we are doing, and at what cost to ourselves.

Lin always waits up for me, no matter how late it gets. When I return, I always go straight to her room, and we sit together, while she smokes an e-spliff. I love Lin’s room, the walls painted dark red, the old Moroccan carpets on the floor, her antique wooden chest, sides carved with a filigreed design, underneath the most intricate wall hanging. A brass lamp mirrors the same design, sending richly woven mosaics of light on her walls when, lighted, it turns and twists above our heads, throwing stars onto our bodies.

Her bed is made of the same wood as the chest and draped with a rich, rust-coloured bedspread. Another brass lamp stands on a nightstand next to the bed, casting a warm glow in the room, and cushions with mirrored covers are scattered on the floor. They belonged to Lin’s aunt Ilona Serfati, who smuggled it all in when she, along with her best friend, Fairuza Dastani, founded the Panah. Those names are legend to all of us. We never get tired of hearing how the two of them came to this place, built it with their own hands, and kept it all a secret under the Agency’s nose. We see their brilliance in the artificial garden they built, the Charbagh, with its flowers, shrubs, hanging vines. Their vision illuminates the sophisticated lighting system they set up to mimic the days and seasons. Their rebellion thrills us, gives us courage when we don’t think we can make it through another night or stand to see another Client.

Ilona has been gone for twenty years, but her treasures make Lin’s room feel rich and warm. They remind Lin that she comes from somewhere, from someone. It’s a good thing she had Ilona to help her grow up. I know all too well what it feels like to be motherless, although I’m luckier than Lin. At least I had my mother for twelve years, though the line that truncates my life into before mother and after mother is as painful as a blade on my skin. I can’t imagine what it’s like to grow up orphaned.

I’m the only one Lin lets inside her room. I’m glad. I’d be jealous of anyone else she’d allow into this inner sanctum. We all respect Lin, want to be in her favour, but I am the one chosen to be her confidante, for reasons that she’s never told me.

She rolls her eyes and half smiles when I lie down on her bed, covered in silicon, shining like a golden child. Lin has to perform miracles with both Clients and our benefactors in order to procure the gold. It’s smuggled from the mines of Gedrosia, a country rich in minerals and ore. They send it to her in small tins, hidden underneath other cosmetics, and she mixes it with silicon for us. Clients always complain that it leaves a shimmering residue in their beds, but they’re only half upset about it. My Clients are always fascinated with it, stroking their fingers against my shimmering skin. Some even say it’s an aphrodisiac, but I think they like that it’s real gold dust: we signal to them that we are even more precious than gold.

Lin knows the ins and outs of our bodies, our secret birthmarks and tattoos, the days of our cycle, how often we wash our hair. We’re racehorses she sends off into the night and takes us back into her safekeeping in the morning.

Every time Lin sees the dark circles under my eyes, she shakes her head. Sometimes she says she can smell insomnia coming off me in depressing grey waves.

‘Come on, Sabine, there’s always something you can try. They’re coming up with new drugs all the time.’

‘No, Lin. Believe me, if there were a magic pill to cure me, I’d take it in a heartbeat. Nothing affects me, not even this,’ I say, pointing at the spliff. It’s true: I’d like nothing better than to shut my eyes and drift away, surrender myself to unconsciousness even for a few short hours, with her watching over me. But there’s no cure for the insomnia, chemical or natural, temporary or permanent. I know Lin thinks I’m being foolish. But Lin’s a sound sleeper; she never understands that my mind can’t rest, that my thoughts chase each other like snakes swallowing their own tails, in a dark chemical wave. I often wonder about my father: I wonder if he misses me, if he wishes we could see each other again. Does he realize the cost of his greed to get me married quickly? Is he sorry? Am I sorry that I came here? You can go into your household as a reluctant bride – that’s only a minor infraction – but there’s no way to bow down to Green City when there’s rebellion in your heart. I had no choice, but five years on, I’m still not at peace with my decision. Maybe insomnia’s my punishment for my reluctance.

‘Joseph always tries to get me drunk. He says it’ll make me sleep.’

‘Aren’t you ever tempted?’ Lin asks me. I know this is a test, so I feign ignorance.

‘What? By the alcohol?’

‘Of course,’ says Lin. ‘What did you think I meant?’ ‘It’s against the rules …’ I intone. ‘No intoxicants, no drugs, no alcohol.’

‘Thank god for your unshakable integrity,’ Lin says, with a straight face, looking at the e-spliff in her hand. ‘Imagine if I were having this conversation with Rupa.’

I smile. ‘Rupa’s only human. And so am I.’ That’s as close as I can get to admitting to Lin that I have tasted the drink Joseph has offered me. ‘You’re so hard on her sometimes.’

‘I have to be. She’s younger and she’s difficult.’

I have felt the sharp side of Rupa’s tongue as much as the others have here, but then I know things about her that the others don’t. So I feel sorry for her, and often defend her when Lin remarks drily on how Rupa’s being ‘difficult’. It’s not easy when you’ve come to the Panah from the outside. Lin doesn’t remember because she’s always called it home.

Whereas Rupa bridles at any decree, I actually like the rules Ilona and Fairuza made for us here all those years ago: not because they make me feel safe, but because they give me a space within which to contain myself. Otherwise I would dissolve, boundaryless, into the air surrounding me. I’ve always needed structure to push up against; it defines me and gives me shape. That’s probably the consequence of growing up in Green City: we’re told what to do, how to behave, even what to think, from the day we’re born. I’m not yet used to thinking for myself. The rules of the Panah provide a halfway house between the strictures of Green City and the complete freedom that exists in places I can’t even imagine.

*******

Notes 1. https://uncannymagazine.com/article/censorship-and-genre-fiction-lets-broaden-our-broader-reality/ Tarun K. Saint acknowledges the help of Dr. Alok Bhalla in framing the questions. .The Beacon wishes to thank Pan Macmillan India, publishers of ‘Before She Sleeps’ for permission to reprint the extract. Before She Sleeps; Bina Shah, Pan Macmillan India, 6th August 2020 ₹599.

Bina Shah is a Karachi-based author of five novels and two collections of short stories. Her latest novel, Before She Sleeps, was published by Delphinium Books in August 2018. A regular contributor to The New York Times, Al Jazeera, The Huffington Post, and a frequent guest on the BBC, she has contributed essays and op-eds to Granta, The Independent, and The Guardian, and writes a regular op-ed column for Dawn, Pakistan’s biggest English-language newspaper. She works on issues of women’s rights and female empowerment in Pakistan and across Muslim countries. In 2020 she was awarded the rank of Chevalier in the Ordre des arts et des lettres by the French Ministry of Culture.

Tarun K. Saint is the author of Witnessing Partition: Memory, History, Fiction (2010, 2nd. ed. 2020). He edited Bruised Memories: Communal Violence and the Writer (2002) and co-edited (with Ravikant) Translating Partition (2001). He also co-edited Looking Back: India’s Partition, 70 Years On in 2017 with Rakhshanda Jalil and Debjani Sengupta. Recently, he edited The Gollancz Book of South Asian Science Fiction (2019). The bilingual (Indian-Italian) SF anthology Avatar: Indian Science Fiction, co-eds. Francesco Verso and Saint, appeared in January 2020. The Gollancz Book of South Asian Science Fiction volume 2 will appear this year.

Also read: Science Fiction Matters…

Science Fiction Matters: South Asian Futures to Come

Leave a Reply