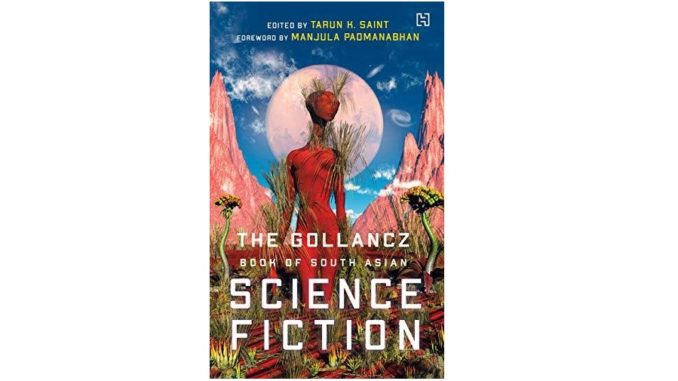

The Gollancz Book of South Asian Science Fiction. 8 March 2019. By Tarun Saint (Editor), Manjula Padmanabhan (Foreword). Hachette India. 424 pages

Tarun K. Saint

T

he Gollancz Book of South Asian Science Fiction is one of the first collections of contemporary (and historic) science fiction (SF) from the subcontinent to appear in the twenty-first century. In this introduction, I hope to highlight the genre’s significance at the global level, as well as elaborate on the basis for the compilation of this omnibus.

Just about two hundred years ago, Frankenstein (1818, revised ed. 1831), Mary Shelley’s novel about the ethical dilemmas untrammelled scientific exploration might usher in, inaugurated the genre of modern SF.1 During a visit to Europe in June 1816, Mary Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Byron and John William Polidori were forced to remain indoors one day as a storm raged outside their villa near Lake Geneva.2 In the evening, they had an animated conversation about ghosts, upon which Byron suggested a ghost-story writing competition (Polidori was the only one to complete his story).That night, a dream occurred to Mary Shelley about a strange phantasm stirring with vital life, beside whom his human creator kneeled. As a result, she began writing a story – a Gothic exploration of the consequences of scientist Victor Frankenstein’s obsession with reanimating corpses through the use of electro-galvanism3 – at the age of eighteen, which became a novel after two years, carving out space for a new genre. The resulting creature is both monster and victim of his creator’s hubris; the achievement of the task of bringing to life the dead (using scientific as well as alchemical/occult means) became a nineteenth-century version of Faust’s unbridled quest for knowledge.

Ever since the publication of Frankenstein the genre of SF has been concerned with the varied consequences of the arrival of modernity, including the advances of scientific knowledge and technology and its sometimes horrific outcomes. Furthermore, the interface between science and the occult, and the possibility of breaching the divide between science and the realm of magic and occult philosophy (as seen in Victor Frankenstein’s fascination with the work of occultist Cornelius Agrippa) has been a recurrent theme in SF, right up to Amitav Ghosh’s The Calcutta Chromosome (1996), steampunk and China Miéville’s oeuvre, testifying to the lasting imprint of Shelley’s concerns.4 The genre’s ability to foreground alternative perspectives with respect to key cultural and socio-political issues subsequently came to the fore in works such as The War of the Worlds (1897), nineteenth-century master of the scientific romance, H.G. Wells’s allegorical take on colonialism, and Yevgeny Zamyatin’s parable of totalitarianism We (1924, new trans. 1993).5 Zamyatin’s masterpiece was in turn one of the inspirations for British author George Orwell’s better-known 1984 (1949).6

Soon after, the twentieth-century American SF maestro Ray Bradbury’s McCarthy-era novel Fahrenheit 451 (1953) depicted a future society where reading was a crime and books were burned, and hence, entire books and works of culture were memorized and shared by members of the resistance group to preserve their contents.7 Later, works of SF by writers in the erstwhile Soviet Union constituted a veritable subculture of dissent. Another SF novel, The Doomed City by Boris and Arkady Strugatsky, perhaps the best of the crop of dissident writers to emerge in the twentieth century in Zamyatin’s wake, evoked the tragic failure of a radical utopian experiment. Written in 1975 in a time of censorship and authoritarian rule, the novel was only published in 1989 after perestroika and glasnost (restructuring and openness) had left their imprint.8

In contrast to this strand of the genre, often critical of science and society, a more conservative strain emerged in the wake of colonialism and imperialism in the late nineteenth century, often with a masculinist thrust, gung-ho for change driven by technology.9 Thus, while the genre has proved enabling for writers seeking to question hegemonic regimes and systems of thought, SF at times has undoubtedly replayed societal stereotypes and rehearsed clichéd notions of identity. For example, much of the pulp SF of the early twentieth century in the United States of America was aimed at an audience of male adolescents or young, often technically trained, men. At its lowest ebb, SF has even served as a propaganda function, as seen in Ronald Reagan’s requisitioning of the services of right-wing-leaning SF writers Larry Niven and Jerry Pournelle (known for their hard-SF style, featuring a strong basis in recent research in scientific disciplines) as speech-writers during the Cold War to help introduce his Strategic Defence Initiative ‘Star Wars’ defence system to the American public. This space laser initiative was vigorously opposed by leading contemporary SF writers of the time like Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke. Clarke described the proposal as a ‘technological obscenity’, while Asimov called it ‘a John Wayne standoff’.10

In the context of the subcontinent, SF’s potential to generate alternative visions of the future has perhaps been insufficiently acknowledged. Despite some innovative and sharply critical SF having appeared in recent years in South Asia, even a speculative fiction manifesto by prominent SF writer Vandana Singh, a contributor in this volume,11 the genre is confined, for the most part, to the children’s section of bookstores, if at all, or placed alongside ‘popular fiction’ genres such as fantasy, barring some regional contexts where it has found a niche.12 It leads one to wonder whether this is the result of SF, or for that matter, speculative fiction,13 not quite having taken in our subcontinental spaces,14 despite the influence of modern scientific thought, industrial development and technological progress, not to mention the recent explosion in the use of social media. Is this lesser, niche status for SF an unwarranted result of the widespread availability and influence of epic and mythological narratives, which may have curtailed the SF impulse?15 Might it be possible to discern in the best SF produced in South Asia in recent times the lineaments of an alternative, perhaps even a South Asian futurism?16 Is it time for Indian/subcontinental SF to step up and make itself heard amidst, what Vandana Singh in her review essay calls, a ‘spiral of silence’17 on a host of issues, ranging from climate change to growing polarization and violence in society, amidst a climate of fear?

This is the right moment for an adequate appreciation of the genre’s critical role in twenty-first-century South Asia, especially at a time when there is a perceptible drift towards modes of irrationalism and bigotry, often with tacit state sanction. While, in the subcontinent, the genre has not been explicitly associated with social movements or protests, in its own quiet way this ‘minor’ genre has whittled away at dominant societal assumptions. A pioneering effort in the subcontinental context is Manjula Padmanabhan’s SF play Harvest (winner of the Onassis Award in 1997) which, set in Bombay in 2010, envisaged a futuristic scenario of harvesting human organs from the ‘Third World’ for sale to recipients in the ‘First World’.18 Padmanabhan has also addressed growing gender hierarchies and imbalances, and the fragility of attempts at forging resistance to modes of bio-politics in her SF novels Escape (2008) and The Island of Lost Girls (2015).19 In a similar vein, writers of SF and speculative fiction Anil Menon in Half of What I Say (2015) and Shovon Chowdhury in The Competent Authority (2013) and Murder with Bengali Characteristics (2015) have made trenchant fictive critiques, in different ways, of state absolutism. Such writings have created alternative templates for the future to come.20

As aficionados of the genre are aware, in the wake of the publication of Frankenstein the genre subsequently evolved with the scientific romances of Jules Verne (in France)21 and H.G. Wells in the late nineteenth century. An era of pulp fiction in the 1920s and 1930s in the USA was launched by innovative editors like Hugo Gernsback (editor of Amazing Stories) and, crucially, John W. Campbell (editor of Astounding Science Fiction, where he played a critical role in shaping the craft of authors like Asimov). Some of the best writers of American SF found a voice during the Golden Age of SF, lasting from the mid-1930s to the mid-1950s, when the triad of Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein and Arthur C. Clarke held sway.22 Later, the New Wave and feminist SF writers of the late 1960s and 1970s were notable for their emphasis on experimentalism, interiority and depth of character and psychology. When SF author and editor Michael Moorcock’s journal, New Worlds, came to the fore in the UK, practitioners of off-beat and avantgarde SF, like British writer J.G. Ballard and Samuel Delany (in America), appeared on the scene.23 Around this time, writers like Ursula K. Le Guin and Philip K. Dick (also from America) inflected the genre in distinctive ways with their interest in so-called ‘soft’ sciences such as anthropology, sociology, psychology and ecology, heralding the emergence of ‘soft’ SF (in contradistinction to the ‘hard’ SF of those like Asimov, trained in the natural and physical sciences)24. The impact of the women’s movement as well as the civil rights movement, and the foregrounding of questions of racial and cultural difference (and the ways these are mediated through language) by African-American writers like Samuel R. Delany (also in the wake of the Amerindian movement, the Latino-Chicano movement and the positing of the need for a rainbow coalition), was felt in the genre as the address of SF began to extend beyond the, often, male and techie readership of the pulps, to ‘the other’. Such approaches were represented in myriad and complex ways in works by Le Guin, James Tiptree Jr. (pseudonym of Alice Sheldon), and later in novels of African-American writer Octavia Butler, which sought to explode the masculinist stereotypes of early SF. 25

Later, the emergence of cyberpunk in the 1980s, with the writings of William Gibson, Bruce Sterling and others, coincided with the invention of the World Wide Web and the Internet (Gibson coined the term ‘cyberspace’ before it existed, in Neuromancer, 1984)26. The rise of humanist SF, with its emphasis on three-dimensional characters, influenced in turn by ‘soft’ social sciences such as sociology, saw the advent of writers like Kim Stanley Robinson among others. In his Mars trilogy and Science in the City series, Robinson brought in extended reflections on environmental issues (this branch of SF has been described as cli-fi, short for climate change fiction). Among other trends that could be identified in this burgeoning field, there was a reinvention of the space opera in innovative ways by Iain M. Banks (in his Culture series) and Alastair Reynolds (in the Revelation Space series), while Octavia Butler reflected on questions of alterity (especially pertaining to race and gender) in an unsettling fashion in her Xenogenesis trilogy, in the light of feminist critiques on positions taken in sciences such as biology and genetics, especially with the advent of biotech and genetic engineering.27

Ann and Jeff VanderMeers’ introduction in The Big Book of Science Fiction has an interesting, if brief, discussion of SF written by authors residing outside the United Kingdom and the USA, including references to Latin American, European, Soviet-era, Chinese and Japanese SF.28 Outside AngloAmerican spaces, some of the more prominent names include Polish writer Stanislaw Lem (Solaris, 1961, tr. 1970), whose writings opened up subversive philosophical possibilities missing in many conventional SF tales;29 and Arkady and Boris Strugatsky (especially Roadside Picnic,1972, tr. 1975) who explored, in unconventional ways, what it means to be human as well as the idea of otherness in the context of situations under authoritarian rule.30 Cixin Liu’s Hugo Award-winning novel The Three Body Problem (2006, tr. 2014) and its sequels The Dark Forest (2008, tr. 2015) and Death’s End (2010, tr. 2106) have shown what non-Western SF might be able to do with the genre, as it retains a situatedness in Chinese culture and history and takes up a dissenting viewpoint that preserves a sense of wonder.31

Ann and Jeff VanderMeer provide an economical definition of SF: ‘… it [SF] depicts the future, whether in a stylized or realistic manner.’32 So, whether that future context is presented in a phantasmagoric way or by using the technical language of hard SF, or whether the future scenario is extrapolated from the present or includes commentary on the past or present, they argue that the story qualifies as SF.33 In their view, this definition allows a delinking of the content or experience offered by SF from market trends that result in the commodification of the genre.34 We may thus steer clear of the easy binarization of ‘literary’ and science or speculative fiction, since there are many SF texts that do cross over these boundaries established by critics and the market.35

To take a recent example of reflection on the genre’s significance, in which this binary was replayed, Amitav Ghosh, in his essay The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, flagged the absence of serious engagement with the issue of climate change in literary fiction, barring a few exceptions.36 When writers did take up the subject, in his view, their work risked being categorized as SF, and thus relegated to the outhouse or periphery. Ghosh refers to Margaret Atwood’s idea that SF and speculative fiction draw on the same deep source, imagined other worlds that are located apart from the everyday one, in another time or dimension, on the other side of a threshold that divides the known from the unknown.37 The era of global warming seems to resist SF, in his view, since it is not happening in an ‘other’ world, nor is it located in another time or dimension.38 Ghosh underlines instead the importance of literary treatment of the subject, engaging with everyday changes occurring in this world, which a few writers of literary fiction have undoubtedly attempted (such as Barbara Kingsolver in Flight Behaviour39, 2012).

Ghosh does, however, acknowledge that the only genre that regularly took up this subject was SF,40 even if in its outhouse of the literary field (his Arthur C. Clarke Award-winning SF novel The Calcutta Chromosome appeared in 1996)41. Ghosh then issues a call for more writers of literary fiction to address the predicament we face due to climate change, overcoming the disdain of collective experience and the non-human in the name of individual human experiences that has resulted from the partitioning of the imaginative from the scientific in this era of modernity.42 In the process, Ghosh perhaps underplays the ongoing efforts of SF writers to imaginatively portray the crises we face (despite his nod to the importance of some SF writers like Clarke, Bradbury and Dick),43 as Vandana Singh has persuasively argued in her critique. Singh instead makes the case for imaginative literature’s (and especially SF and speculative fiction’s) ability to alert us to, what she terms, ‘paradigm blindness’ or a failure to look beyond the paradigm in which one is located and the modes of constructing reality therein.44

Ironically enough, one of the earliest instances of Indian SF, a story by the renowned Bengali scientist Jagadish Chandra Bose, ‘Niruddesher Kahini’ (‘The Story of the Missing One’, 1896), revised and published as ‘Polatok Toofan’ (1921, tr. ‘Runaway Cyclone’), actually dealt with an extreme instance of climatic variations – a life-threatening situation faced by the crew of a ship caught in a cyclone at sea.45 This story written in Bengali, by Bose, a scientist known for his research on electromagnetic waves, was crafted in response to an advertisement issued by a hair oil company announcing a science-based story writing competition, the only condition being that each story would have to feature the hair-oil in question. Indeed, in Bose’s story, a scientist aboard the ship in a moment of danger during the cyclonic storm eventually recalls carrying a bottle of hair-oil with him. He pours this on the waves with effects that are reminiscent of the butterfly effect propounded much later by Edward Lorenz (in the 1960s), according to which a minor perturbation might have major cumulative consequences.46 The life-threatening waves are calmed by the oil’s soothing effects, and the ship is saved. While the exposition of the theory of surface tension underlying this story by the author indicates a somewhat utopian faith in science, it is unlikely that such scientific panacea exists for contemporary ecological crises. Nonetheless, the story in question does anticipate recent concern for abrupt (and potentially destructive) transformations in the natural world and the potential for human/technological intercession, here portrayed in a benevolent light. 47

A detailed historical survey of subcontinental SF is out of the purview of this introduction, given the vast scope of the subject and varied linguistic skills required. I will nevertheless try to highlight a few trends and refer to select important early authors and texts, based on studies in the regional context in a few major languages.

One of the first Bengali (and likely subcontinental) SF stories dealing with innovative and imaginary technology was Hemlal Dutta’s ‘Rahashya’ (‘The Mystery’), which appeared in a journal titled Bigyan Darpan in 1882. Jagadananda Roy’s ‘Shukra Vraman’ (Travels to Venus’) was published in Varati magazine in 1895, and later republished in the volume Prakritiki in 1914.48 The story by J.C. Bose mentioned earlier, ‘Niruddesher Kahini’ (‘The Story of the Missing One’), appeared in 1896, with a revised version in 1921, titled ‘Polatok Toofan’ (‘Runaway Cyclone’).49 Debjani Sengupta in her essay ‘Sadhanbabu’s Friends: Science Fiction in Bengal from 1882 to 1961’ mentions an early twentieth-century work by Sukumar Ray (the father of Satyajit Ray) bringing in a satirical take on scientists in ‘Heshoram Hushiyarer Diary’ (‘The Diary of Heshoram Hushiar’) – possibly inspired by Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World50, and later Premendra Mitra’s ‘Piprey Puran’ (‘The Story of the Ants’) and ‘Mangalbairi’ (‘The Martian Enemies’) as taking the genre forward, with Ray’s works often aimed at a young audience.51 Film-maker and writer Satyajit Ray’s Professor Shonkhu series (published from 1961 till the author’s death) unfolded in a new direction, presented in the form of diary entries documenting the adventures of an eccentric scientist with a sense of humour.52 Satyajit Ray himself became the president of the SF Cineclub, with Premendra Mitra as vice-president and Adrish Bardhan as secretary, in 1966, indicating that this thriving SF subculture traversing film and literature had considerable support among Bengali viewers and readers.53

In his editorial for the special issue of Muse India on Science Fiction, Sami Ahmad Khan refers to Pandit Ambika Dutt Vyas’s ‘Ascharya Vrittant’ published in the magazine Piyush Pravaha (1884), and Babu Keshav Prasad’s ‘Chandra Lok ki Yatra’ published in the magazine Saraswati (1900) as examples of writing in Hindi that qualify as early or proto-SF.54 However, SF appears not to have emerged as a major genre in Hindi and Urdu literature, despite the popularity of translations of Jules Verne and H.G. Wells in those languages.55 Khan also cites proto-SF works in English, such as Kylas Chunder Dutt’s anti-imperial ‘A Journal of Forty-Eight Hours of the Year 1945’, which appeared in The Calcutta Literary Gazette, 6 June 1835.56 Dutt was an eighteen-yearold student of Hindu College, Calcutta, later renamed Presidency College, when he wrote this story, depicting an imaginary anti-colonial revolt in the century to come, for The Calcutta Literary Gazette (6 June 1835). Such a subversive outlook might not have been possible in print after the 1857 uprising, when censorship of anti-colonial writings was imposed in greater measure.57 Shoshee Chunder Dutt’s ‘The Republic of Orissa: A Page from the Annals of the 20th Century’ (1845),58 carried forward this youthful spirit of questioning colonial power as well as local hierarchies, while Rokeya Sakhawat Hussain’s remarkable feminist utopia Sultana’s Dream (1905) appeared at the dawn of the twenty-first century, becoming the basis for subsequent radical imaginings of alternatives to war and patriarchy.59 Each of these early SF texts in English interrogate the power structures in place at the time – whether imperialism, slavery (the re-imposition of which leads to a tribal rebellion in Shoshee Dutt’s story), the likely persistence of hegemonic systems after independence, or extant patriarchal assumptions about the role of women in governance.60 SF critic Suparno Banerjee identifies a more sceptical and critical outlook in ‘Anglophone’ writing, or Indian writing in English, especially in works that have appeared after the 1990s, in comparison to early regional writing, where the writing often seems to rely on Western SF for its model.61 As he shows, such writing often seeks to emulate SF narratives of the Golden Age in its valorization of and belief in the benefits of science and technology, barring some exceptions (such as Sukumar Ray)62.

The anthology It Happened Tomorrow, edited by Marathi SF writer and critic Bal Phondke and published in 1993, was one of the first serious attempts to collate and compile Indian SF stories, mainly in translation.63 In the collection, scientific problems set in an Indian milieu feature in the main, while some make critical references to the social and political uses of science and technology.64 In the preface to the volume, Phondke discusses the regional contexts for early works, including Marathi and Bengali as the major languages in which the genre flourished, appearing often in small regional magazines and periodicals.65 This efflorescence of the genre in these coastal areas may have occurred as a result of the spread of scientific education and people’s science movements in such historically cosmopolitan contexts (after all, the Bengal Renaissance came about as a response to the advent of modernity under the colonial aegis)66.

Phondke’s assertion that Indian SF may be categorized not so much by the geographical origin of the authors as by ‘the cultural and social ambience which gives it its soul’ certainly has an idealistic view at its core.67 Phondke’s preface leans towards Marathi (the strongest current, in his terms) in its delineation of the history and contours of regional SF (though he does acknowledge, among others, the contributions of Adrish Bardhan as editor of Fantastic, a Bengali SF magazine), as Assamese writer Dinesh Chandra Goswami’s Sahitya Akademi paper about Indian SF and fantasy does towards Asomiya.68 While this is to be expected, given the background and training of these editors/ authors, tracing this history can indeed seem at times like ‘hunting a snark’, as Anil Menon puts it in his witty essay on the subject.69 The task of assembling and historicizing subcontinental, let alone Indian, SF still awaits a dedicated team in the future.70

Suparno Banerjee’s more recent 2010 study seeks to position Indian SF in the context of postcolonial debates, and discusses major texts by Indian writers as well as SF novels set in India by Western writers. His emphasis on the dialectics of authority (affirming Western science and technology) and subversion (at times rather uncritically, in the name of a ‘pure’ indigenous epistemology) in Indian SF writings and critical survey of the field is a useful beginning of what needs to become a comprehensive critical discourse. As Banerjee shows, SF criticism needs to be equally alert to our colonial inheritance and the pitfalls of both ill-thought-out versions of Orientalist futurism (Orientalist futurism refers to SF novels set in a future India that replay Orientalist ideas about the East and India in particular), as well as simplistic claims as regards the superiority of native knowledge systems, with knee-jerk recourse to the greatness of ‘Vedic science’.71

Colonial era proto-SF was succeeded by a range of writings in the major Indian languages as well as in English. Nation-building imperatives and the need to propagate the ‘scientific temper’ were likely key objectives of much of the writing of the early phase after Independence, often animated by an idealized view of science and technology and a didactic impulse.72 Yet, as Shiv Viswanathan points out in his foreword to Alternative Futures, some strands of the national movement were futuristic in outlook, keen to provide alternatives to positivist science and instrumental rationality. Viswanathan especially cites Gandhi’s ashrams as laboratories for the future, where swadeshi and Swaraj became the basis for a different mode of thinking and being, opening up the basis for eco-Swaraj (radical ecological democracy)74 in the future. With the rise of environmentalism in the 1960s and 1970s,75 and the subsequent critiques of the excesses of modern science and instrumental rationality73 by J.P.S. Uberoi, Vandana Shiva, Ashis Nandy and Shiv Viswanathan among others, a greater degree of scepticism about science and technology and the developmental discourse came to the fore.76 One of the landmark novels that redefined the contours of Indian SF in the wake of such rethinking, Amitav Ghosh’s The Calcutta Chromosome, looks back at the history of colonial science and normative patterns of scientific research and development prevalent. The novel achieves a critical perspective on the advent of modernity in colonial India during the process of reconstructing the history of the discovery of the malaria parasite in fictive form.77

Even so, many post-Independence subcontinental SF writers happened to be scientists or teachers of science, such as astrophysicist Jayant Narlikar in Marathi and English (he studied under physicist Fred Hoyle, author of The Black Cloud, a novel anticipating the discovery of molecular clouds between stars), teacher of physics Dinesh Chandra Goswami in Asomiya, and zoologist Sukanya Datta in English.78 Among non-scientists writing SF in the ‘popular’ vein, Sujatha Rangarajan’s writings in Tamil are well-known, while Ruchir Joshi’s expansive experimental novel The Last Jet Engine Laugh (2001) included SF elements with a time-span from 1930 to 2030.79 Critiques of a monolithic view of science and new perspectives on destructive development underpinned by a desire for ecological justice are opening up new avenues for self-critical SF to follow.80 This greater degree of self-reflexivity and meta-awareness of both science’s and the genre’s fallibility (also leading to a fluidity of genre-borders) is apparent in the best work of SF writers since the 1990s, including Manjula Padmanabhan, Vandana Singh (The Woman Who Thought She Was a Planet, 2008, Ambiguity Machines and other Stories, 2018, nominated for the Philip K. Dick Award, 2018), Anil Menon, (The Beast with Nine Billion Feet, 2009), Rimi B. Chatterjee (Signal Red, 2005), Priya Sarukkai Chhabria (Generation 14, 2008) and Shovon Chowdhury.81 Recently, award-winning author of literary fiction M.G. Vassanji has written a major SF novel, Nostalgia, indicating the fluidity of genre borders.82

A younger generation of writers such as Suraj Clark Prasad (aka Clark Prasad), Sami Ahmad Khan, Samit Basu (leaning towards fantasy), as well as other writers of South Asian descent such as Mimi Mondal (now living in the USA, nominated for the Hugo Award in 2018 for her co-edited study of Octavia Butler, Luminescent Threads), S.B. Divya (nominated for the Nebula Award for her debut novel, Runtime, 2016, based in the USA), Vina Jie-Min Prasad (in Singapore), Premee Mohamed (in Canada), Nur Nasreen Ibrahim (Salam Award finalist from Pakistan, now based in the USA) and Indrapramit Das (writing as Indra Das, in Kolkata and North America) are attempting to further expand the scope of the genre through their innovative choice of themes – such as the urgent challenges posed by biotechnology, the impact of social media and social technology on society, environmental degradation, changing gender dynamics, sectarian strife and hidebound identity politics – and styles (often highly in dividualized). We can discern in their novels, stories and poems twenty-first century SF’s intersectional potential in tackling questions of difference along fraught lines of gender, community, race and sexuality in both subcontinental and diasporic locations.83

The more all-encompassing term, speculative fiction, may be more appropriate for narratives which often blur generic boundaries (the term speculative non-fiction has now come into play as well), and seem to be more influenced by debates in the social sciences and the humanities,84 even though scientist-writers like Vandana Singh and Anil Menon do continue to bring in hard science/technology based allusions, albeit with a critical understanding of the limits to technology-driven progress.85 The sub-genre of speculative poetry is included here as well, a form of poetic expression exploring various facets of human experience through a speculative lens.86 This anthology, however, restricts its ambit by not including retold mythology, mytho-fantasy and out-and-out fantasy (in which anything can happen and no set rules apply)87.

The genesis of this anthology was not so much the imperative to anthologize the work of earlier writers (though some samples of early SF are provided here), or to further explore the antinomies of postcolonial discourse (including postcolonial SF; see Hopkinson and Mehan, eds., So Long Been Dreaming88). Rather, a sense of disturbance with the situation in contemporary South Asia led to the composition of the concept note which was sent out to both established and younger subcontinental writers in English. If not quite a competition to write a ghost story, the idea was to impel contemporary writers to engage with the present and future, using an SF lens, in this seventy-second year of Independence and the Partition. What might the subcontinent look like, about, seventy years from now?

For the subcontinent, and India in particular, has been rocked by such a number of crises in the last few years that it has often seemed we are living out the plot of a SF novel on a daily basis.89 The annus horribilis 1984 was, for many, a shock, almost living up to Orwellian predictions in the subcontinent. The anti-Sikh pogrom in Delhi that year led to intensive introspection among many about how such large-scale, state-abetted collective violence could occur in India’s democracy, while the Bhopal industrial disaster the same year reminded us of the appalling consequences of reckless and unchecked proliferation of technology in the name of profit. In recent years, the continuing degradation of the environment, the basis for survival for marginalized communities, the threat to freedom of speech with growing intolerance in society across South Asia, the multiplication of incidents featuring violence reminiscent of the Partition (now including videotaped vigilante actions by mobs) with the added complication of mediatized forms of politics and the emergence of social media-based trolls and WhatsApp pressure groups, as well as the targeted killing of authors and journalists, has posed new challenges for commentators and writers.

The stories and poems sent in by writers of three countries of South Asia in response to the concept note (not all of those who were approached did so), often feature world-building and dystopian realities eerily reminiscent of the present, sometimes presented in a satirical light, with elements of black humour. It is the tension between the implicit utopian imaginings of alternative South Asian futures and the representation of stark dystopias that makes these thought experiments in the SF mode so interesting.90 This anthology also includes selected sample stories in translation from some major regional languages, written during the twentieth century. …..

….Taken together, these stories and poems may indicate the direction of alternative South Asian futures to come, as well as the emergence of a subcontinental SF sensibility attuned to socio-cultural nuances and issues that are local as well as global. We can discern here a shared counter-vision, as these writings at their best bear witness to, at times, uncomfortable truths, albeit displaced into ‘other’ timelines and spaces. Such fictive extrapolation provides a perspective rather different from the futurologists, with an emphasis on the human and culturally specific side of the story.91 The future of subcontinental SF, as evidenced by this volume, thus seems promising indeed, even in the face of grim portents in the socio-cultural domain in the subcontinent and seemingly inexorable transformations of the ecological basis for life that are threatening the very existence of the most vulnerable, not just in South Asia. The hope is that for readers this anthology will provide a prism refracting the vivid and at times contrarian imaginings of contemporary South Asian SF.

******

Notes 1. Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, 1818, reprint, New Delhi: Worldview, 2002, ed. with an introduction by Maya Joshi. Also see, Brian Aldiss and David Wingrove, Trillion Year Spree, London: Gollancz, 1986, 36–52. 2. ‘Preface’ in Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, ed. Maya Joshi, New Delhi: Worldview, 2002, vi. The frequent storms that year were a result of the eruption of a volcano, Mount Tambora in Indonesia the previous year, which disrupted weather patterns across the world. http://lithub.com/mary-shelley-abandoned-by-her-creator-andrejected-by-society/ (accessed 28 January 2018). 3. Brian Aldiss and David Wingrove, Trillion Year Spree, London: Gollancz, 1986, 36–52. 4. I am indebted to Geeta Patel for this idea. Also see Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, 1818, reprint, New Delhi: Worldview, 2002, ed. Maya Joshi, 29–33, and Amitav Ghosh, The Calcutta Chromosome: A Novel of Fevers, Delirium and Discovery, New Delhi: Ravi Dayal, 1996. China Mieville’s work often veers towards science fantasy; see, for instance, the blending of elements of crime fiction, SF, and the fantastical in Miéville, The City and The City, London: Pan, 2009. 5. http://www.planetpublish.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/The_War_of_ the_Worlds_NT.pdf (accessed January 2019). See Clarence Brown, ‘Introduction: Zamyatin and the Persian Rooster’ in Yevgeny Zamyatin, We, 1924, new English trans. by Clarence Brown, London: Penguin, 1993, xi–xxvi. Zamyatin went into exile after the controversy and personal attacks following the book’s initial publication outside the Soviet Union – the novel only appeared in his homeland in 1988. 6. George Orwell, 1984, London: Secker and Warburg, 1949. 7. Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451, New York: Ballantine, 1953. Bradbury’s novel, as literary historian and cultural critic Geeta Patel points out, plays with a kind of Christian Puritanism and its tense relationship with the transformative power of art and literature, manifested in the past most strongly in the case of Girolamo Savonarola, the Florentine monk responsible for the original ‘bonfire of the vanities’ when items of ‘luxury’, including ‘indecent’ books were burned in the public square in Florence in 1497. Personal communication. Also see https:// www.historytoday.com/richard-cavendish/execution-florentine-friar-savonarola ( accessed 3 May 2018). 8. Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, The Doomed City, 1989, tr. Andrew Broomfield, Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2016. 9. I am indebted to Anil Menon for this idea. In contrast, Cory Doctorow’s utopian novel Walkaway (London: Head of Zeus, 2017) presents a future society of dropouts (‘walkaways’) who contest the basis of late-capitalist society through the creation of survivor states, reliant on the creative redeployment of new ‘soft’ technologies like 3D printing, even while refusing to succumb to the surveillance state’s attempts to rope them in using war-propelled ‘hard’ technologies. There has been a conservative backlash to attempts to bring in more diversity and complexity in the American SF awards, the charge led by the so-called Sad (and later Rabid) Puppies. See https://newrepublic.com/article/121554/2015-hugo-awards-andhistory-science-fiction-culture-wars (accessed 18 May 2018). 10.https://www.thrillist.com/entertainment/nation/strategic-defenseinitiative-reagan-star-wars-jerry-pournelle-larry-niven (accessed 26 December 2017). 11.‘A Speculative Manifesto’, in The Woman Who Thought She Was a Planet and Other Stories, 2008, reprint, New Delhi: Zubaan, 2013, 200–03. 12. Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay, Aakriti Mandhwani and Anwaisha Maity, ‘Introduction – Indian Genre Fiction: Languages, Literatures, Classifications’, https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Bodhisattva_Chattopadhyay/ publication/326416187_Indian_genre_fiction_languages_literatures_ classifications/links/5b4c6f65a6fdccadaecf70bb/Indian-genre-fiction-languagesliteratures-classifications.pdf, (accessed 11 November 2018). As Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay et al argue, SF has never been as ‘popular’ as other mass cultural genres in the subcontinent despite having emerged from the same crucible and mass genre cultural system, including pulps and periodicals. Instead, SF had a perceived ‘supra-educational’ role here, as a genre for children and young adults, unlike in the West, where it is seen as a genre for adults. 13. Speculative fiction is a more general term, according to one definition, ‘a broad literary genre encompassing any fiction with supernatural, fantastical, or futuristic elements’, http://www.dictionary.com/browse/speculative-fiction (accessed 1 February 2018). In Cecilia Mancuso’s terms, speculative fiction was a term used by science fiction avant-gardists to distinguish their ‘serious’ work from pulp fiction featuring ‘monsters and spaceships’ in Margaret Atwood’s phrase, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/aug/10/speculative-or-sciencefiction-as-margaret-atwood-shows-there-isnt-much-distinction (accessed 4 February 2018). Similarly, Fredric Jameson differentiates between the European art tradition of H.G. Wells’s ‘scientific romances’ or speculative fiction and the commercially driven American pulp tradition, while referring to the work of Olaf Stapledon. See Jameson’s ‘Introduction’ in Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions, 2005, reprinted, London: Verso, 2007, fn.5, xiii. Also see the more hopeful conversation about recent Indian speculative fiction at http:// strangehorizons.com/non-fiction/remaking-the-difference-a-discussion-aboutindian-speculative-fiction/ (accessed 1 May 2018). 14. Ashok Vajpeyi, India Dissents: 3,000 Years of Difference, Doubt and Argument, New Delhi: Speaking Tiger, 2017, esp. 16–18, 55, 65–70, 163–68, 403–05, 428–33, 440–44. This recent volume begins with the Vedic era materialist Charvaka, and includes the pre-modern voices of Kabir and the Sufis as well as pieces by modern figures like Ismat Chughtai and Saadat Hasan Manto, an essay by Amartya Sen, as well as social media-based writings by Kiran Nagarkar and Mrinal Pande, among others, mapping the spectrum of dissenting views across history up to the present. SF writers do not, however, figure at all in this volume. 15. Shiv Viswanathan, ‘Foreword’ in Alternative Futures: India Unshackled, eds. Ashish Kothari and K.J. Joy, New Delhi: UpFront Publishing House, 2017, vii–xi, esp. vii. According to social scientist and cultural critic Shiv Viswanathan, SF has not had the same following as detective fiction in the subcontinent partly because our mythology is so replete with aliens, monsters and witches. 16. South Asian futurism may be comparable to an extent to the notion of afrofuturism, as it envisages a different collective and transnational future while invoking SF elements, in the face of often intractable power structures and hierarchies inherited from the past. For more on afrofuturism, see https://www. theguardian.com/culture/2015/dec/07/afrofuturism-black-identity-future-sciencetechnology (accessed 7 February 2018). I am indebted for this parallel to Ananya Jahanara Kabir. Also see Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay’s reflections at http:// momentum9.no/materials/is-science-fiction-still-science-fiction-when-it-is-writtenon-saturn-or-aliens-alienation-and-science-fiction/ (accessed 7 February 2018). 17. See Singh’s review essay at http://strangehorizons.com/non-fiction/ reviews/the-unthinkability-of-climate-change-thoughts-on-amitav-ghoshs-the-greatderangement/ (accessed 26 December 2017). 18. Manjula Padmanabhan, Harvest, 1997, revised and expanded edition, Gurgaon: Hachette India, 2017. 19. Manjula Padmanabhan, Escape, New Delhi: Picador, 2008, reprinted, Gurgaon: Hachette India, 2015, and The Island of Lost Girls, Gurgaon: Hachette India, 2015. 20. Anil Menon, Half of What I Say, New Delhi: Bloomsbury, 2015; Shovon Chowdhury, The Competent Authority, New Delhi: Aleph Book Company, 2013 and Murder with Bengali Characteristics, New Delhi: Aleph Book Company, 2015. 21. See Jules Verne, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea: An Underwater Tour of the World, 1869–72, Trans. F. P. Walter 1993, reprinted London: Collector’s Library, 2010. 22. See for instance Isaac Asimov, I, Robot, 1950, reprinted, New York: Bantam, 1991, Robert A. Heinlein, Have Space Suit—Will Travel, 1958, reprinted, New York: Ballantine Books, 1977, Arthur C. Clarke, Rendezvous with Rama, 1973, reprinted, London: Gollancz, 2006. 23. See Michael Moorcock, Behold the Man, 1969, reprinted, London: Gollancz, 1999; J.G. Ballard, The Drought, 1965, reprinted, London: Paladin, 1985; Samuel R. Delany, Babel-17, 1967, reprinted London: Gollancz, 1999. 24. See, for instance, Ursula K. Le Guin, The Left Hand of Darkness, 1969, reprinted, London: Orbit, 2009, and The Dispossessed, 1974, reprinted, London: Millenium, 1999. Also, Philip K. Dick, The Man in the High Castle, 1962, reprinted,. London: Penguin, 1965, and Ubik, 1969, reprinted London: Millennium, 2000. Ursula K. Le Guin’s passing has led to a reappraisal of her work and numerous tributes. See Vandana Singh’s acknowledgement of her influence at https://vandanasingh.wordpress.com/2018/01/26/true-journey-is-return-a-tribute-to-ursula-k-leguin/#more-394 (accessed 30 January 2018). 25.This paragraph draws on Ann and Jeff VanderMeer, ‘Introduction’ in The Big Book of Science Fiction, New York: Vintage, 2016, xiii–xxxi, esp. xxiii–xxv. Also see Adam Roberts, Science Fiction, New York: Routledge, 2000, esp. 47–117, and Octavia Butler’s revisiting of the history of slavery through time travel in her novel Kindred, 1979, reprinted, Boston: Beacon, 1988. Delany’s statement about racism and SF is significant in this regard. See http://www.nyrsf.com/racism-and-science-fiction-. html (accessed 17 May 2018). 26. Ibid., xxvi–xxvii, also William Gibson, Neuromancer, 1984,20 reprinted, London: Harper Voyager, 1995, and Adam Roberts’ discussion of the novel in Roberts, Science Fiction, New York: Routledge, 2000, 169–80. 27.This paragraph follows the VanderMeers’, ‘Introduction’, xxvi -xxviii. See, for instance, Kim Stanley Robinson, Green Mars, 1994, reprinted, London: Harper Voyager, 2009, and Robinson, Green Earth: The Science in the Capital Trilogy, 2007, omnibus ed., London: Harper Voyager, 2015. Also see, Iain M. Banks, Look To Windward, 2000, reprinted, London: Orbit, 2010; Alastair Reynolds, Revelation Space, 2000, reprinted, London: Gollancz, 2013. I am indebted to Geeta Patel for her insights as regards Butler’s work. Also see, Octavia Butler, Xenogenesis trilogy (Dawn, 1987, Adulthood Rites, 1988, Imago, 1989), reprinted as Lilith’s Brood, New York: Grand Central Publishing, 2000. 28.Ibid., xxv–xxvi. In contrast, Brian Aldiss’s 2007 SF anthology does not refer to or include any non-Western SF, except for a story by Ted Chiang, who was born and is based in the USA. See Aldiss, ed., A Science Fiction Omnibus, London: Penguin, 2007. 29. Stanislaw Lem, Solaris, 1961, trans., Orlando: Harvest, 1970. Also see his essay on science fiction, in which Lem takes a sharply critical view of American SF, with the exception of Philip K. Dick’s work, in Stanislaw Lem, ‘Science Fiction: A Hopeless Case—with Exceptions’, in Stanislaw Lem, Microworlds: Writings on Science Fiction and Fantasy, ed. Franz Rottensteiner, 1984, reprinted, London: Mandarin, 1991, 45–105. 30. Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, Roadside Picnic, 1972, tr. 1975, reprinted, London: Gollancz, 2000. Andrei Tarkovsky directed major films based on these two novels, Solaris in 1972 and Stalker (based on Roadside Picnic) in 1979. See http://sensesofcinema.com/2002/great-directors/tarkovsky/#film (accessed 3 March 2018). 31. A selection of some of the best of international SF (also including two South Asian exemplars) has been brought together in the VanderMeers’ anthology, The Big Book of Science Fiction, including a story by Cixin Liu. Also see Cixin Liu, The Three Body Problem, 2006, tr. Ken Liu, London: Head of Zeus, 2014; The Dark Forest, 2008, tr. Joel Martinsen, London: Head of Zeus, 2015; and Death’s End, 2010, tr. Ken Liu, London: Head of Zeus, 2016. 32. VanderMeers, ‘Introduction’, xv–xvi. According to SF historians Brian Aldiss and David Wingrove, in Trillion Year Spree (1986), ‘Science fiction is the search for a definition of mankind and his status in the universe which will stand in our advanced but confused state of knowledge (science), and is characteristically cast in the Gothic or post-Gothic mode.’ Aldiss and Wingrove, 25. 33. VanderMeers, ‘Introduction’, xv–xvi. 34. bid., xvi. 35. For instance, Kurt Vonnegut deployed SF devices in his absurdist antiwar novel about the horrific Dresden bombings during the Second World War; his meta-fictional narrative features an (unsuccessful) science fiction writer named Kilgore Trout. See Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse 5, 1969, reprinted, London: Vintage, 1991. Nobel Prize winner Kazuo Ishiguro’s chilling futuristic narrative evoking the interior world of clones raised to donate organs, Never Let Me Go, London: Faber and Faber, 2005, is a notable example of cross-over SF. 36. Amitav Ghosh, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, New Delhi: Penguin Random House, 2016. 37.Ibid., 97. On the difference of viewpoint between Atwood and Le Guin as regards science fiction and speculative fiction , see Le Guin’s review article, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2009/aug/29/margaret-atwood-year-offlood?CMP=share_btn_fb (accessed 4 February 2018). For instances of Atwood’s cli-fi style speculative fiction (part of her MaddAdam trilogy about man-made ecological catastrophe), see Margaret Atwood, Oryx and Crake, 2003, reprinted, London: Virago, 2009, Atwood, The Year of the Flood, 2009, reprinted, London: Virago, 2013 and Atwood, MaddAddam, 2013, reprinted London: Virago, 2014. Fredric Jameson cites Darko Suvin’s view that utopia is a subgenre of science fiction, in his ‘Introduction’, Archaeologies of the Future, xiv. For a notion of South Asia which is ‘civilisational, reciprocal and local in its diversity’, see Shiv Viswanathan, http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/talk-like-a-south-asian/ article22828352.ece (accessed 25 February 2018). 91. For recent futurological speculation forecasting the emergence of suprahuman entities using bioengineering and data-driven algorithms, see Yuval Noah Harari, Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow, 2015, tr., London: Vintage, 2017, esp. 428–62. 38. Amitav Ghosh, The Great Derangement, 97–98. 39. Ibid., 221. Also see Barbara Kingsolver, Flight Behaviour, London: Faber and Faber, 2012. For another engagement with environmental disaster in the satirical mode by a major novelist, see Ian McEwan, Solar, 2010, reprinted, London: Vintage, 2011. 40. As is well-known, SF has negotiated major issues of the time including environmental degradation through extrapolation and displacement into futuristic/ otherworldly contexts (often using techniques of cognitive estrangement, a term coined by prominent SF critic Darko Suvin). According to Suvin, ‘SF is, then, a literary genre whose necessary and sufficient conditions are the presence and interaction of estrangement and cognition, and whose main formal device is an imaginative framework alternative to the author’s empirical environment.’ See Darko Suvin, ‘Estrangement and Cognition’ at http://strangehorizons. com/non-fiction/articles/estrangement-and-cognition/ (accessed 15 December 2017). However, as Geeta Patel observes, previous dystopian and post-apocalyptic narratives (at times allegorical in scope) about resource depletion and environmental degradation did exist and were folded into SF as the genre evolved. Personal communication. Cormac McCarthy’s post-apocalyptic novel, The Road, London: Picador, 2006, is a contemporary instance of this. 41. Amitav Ghosh, The Calcutta Chromosome: A Novel of Fevers, Delirium and Discovery, New Delhi: Ravi Dayal, 1996. 42. Ghosh, The Great Derangement, 86–96. 43. Ibid., 96. 44. See Vandana Singh’s review essay http://strangehorizons.com/non-fiction/ reviews/the-unthinkability-of-climate-change-thoughts-on-amitav-ghoshs-the-greatderangement/ (accessed 15 December 2017). 45. Also see, Vandana Singh’s and Anil Menon’s commentary at http:// strangehorizons.com/fiction/introduction-to-runaway-cyclone-and-sheeshaghat/ (accessed 15 December 2017). For a recent translation by Bodhisattva Chattopadhyaya, see http://strangehorizons.com/fiction/runaway-cyclone/ (accessed 15 December 2017). 46.See http://www.stsci.edu/~lbradley/seminar/butterfly.html (accessed 15 December 2017). In 1952, Ray Bradbury’s story ‘A Sound of Thunder’, showed the disastrous cumulative effects over the years of the inadvertent killing of a butterfly during a safari to the age of dinosaurs, in an age of time travel, http://mrjost.weebly. com/uploads/1/2/8/8/12884680/a_sound_of_thunder_-_text.pdf (accessed 25 January 2018). 47. For instance, see Manjula Padmanabhan’s futuristic take on air pollution in Delhi in the 1980s, and the social attitudes toward the problem in her SF story ‘Sharing Air’ (Kleptomania: Ten Stories, New Delhi: Penguin Books India, 2004, 83–90). 48. Personal communication, Dip Ghosh, based on his article in Bengali https://kalpabiswa.com/article/first_science_fiction/, accessed Nov. 4 , 2020. Also see Debjani Sengupta, ‘Sadhanbabu’s Friends, Science Fiction in Bengal from 1882–1961’, in Sarai Reader 2003: Shaping Technologies, at http://archive.sarai.net/ files/original/e067355930e46f0f188b0fc0e5348cc5.pdf (accessed 15 December, 2017). 49. http://strangehorizons.com/fiction/introduction-to-runawaycyclone-and-sheesha-ghat/ (accessed 15 December 2017). 50. See Sukumar Ray, ‘The Diary of Heshoram Hushiar’, in Satyajit Ray, Travails with the Alien: The Film that was Never Made and other Adventures with Science Fiction (Noida: Harper Collins India, 2018, 190–98). 51. Debjani Sengupta, ‘Sadhanbabu’s Friends’. Also see the discussion of the history of kalpobigyan (the Bengali term for SF) at http://www.sfencyclopedia.com/ entry/bengal (accessed 15 December 2017). Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay proposes that kalpobigyan might take the place of terms like SF or speculative fiction while referring to non-Anglocentric genre fiction, especially but not only from Bengal. See http://strangehorizons.com/non-fiction/articles/recentering-science-fictionand-the-fantastic-what-would-a-non-anglocentric-understanding-of-science-fictionand-fantasy-look-like/ (accessed 13 March 2018). Also see Chattopadhyay’s critical discussion of Premendra Mitra’s Ghanada stories, in comparison to and as a redoing of the colonialist stories of Joseph Jorkens, written by Edward Plunkett, Lord Dunsany (1878–1957) at http://humanitiesunderground.org/aliens-of-the-sameworld-the-case-of-bangla-science-fiction/ (accessed 13 March 2018). According to cultural commentator Sandip Roy, in Bangladesh Humayun Ahmed and Zafar Iqbal are two scientists who have led the field with respect to SF. See ‘The Future in the Past’ at http://indianexpress.com/article/lifestyle/books/the-future-in-thepast-5013283 (accessed 7 January 2018). 52. Ibid. A film version based on Ray’s Professor Shonkhu stories, directed by his son, Sandip Ray, has released in 2018. See Roy, ‘The Future in the Past’ at http://indianexpress.com/article/lifestyle/books/the-future-in-the-past-5013283 (accessed 15 December 2017). Satyajit Ray’s script about an extraterrestrial visitor (titled The Alien) circulated in Hollywood, but the project fell through eventually. This script’s influence on Steven Spielberg’s E.T. became a matter of controversy subsequently. See Satyajit Ray, Travails with the Alien, esp. 71–189. Also see Ashis Nandy’s fascinating discussion of Ray’s science fiction, highlighting his portrayal in three SF stories of the tragedy of a creative person in a conformist society, ‘Satyajit Ray’s Secret Guide to Exquisite Murders: Creativity, Social Criticism and the Partitioning of the Self’, in Ashis Nandy, The Savage Freud and Other Essays on Possible and Retrievable Selves, New Delhi: OUP, 1995, reprinted 2000, 237–66. SF critic and literary historian Suparno Banerjee refers to Ray’s SF stories as an instance of post-colonial hybridity, in Banerjee, ‘Other Tomorrows: Postcoloniality, Science Fiction and India’, 2010, LSU Doctoral Dissertations, 3181, http://digitalcommons. lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3181, 73, 39–41 (accessed 15 December 2017). 53. See Satyajit Ray, Travails with the Alien, 28–33. 54.Sami Ahmed Khan, ‘Editorial’, Muse India Issue 61: May–June 2015, special issue on SF at archive, www.museindia.com (accessed 25 July 2017). For a discussion of the history of Hindi SF see ‘Science Fiction in Hindi – An Overview’ by Arvind Mishra, which mentions Rahul Sankrityayan’s futuristic Baeesvi Sadeen, written in 1924, at http://indiascifiarvind.blogspot.in/2007/08/science-fiction-in-indiaanoverview.html (accessed 3 March 2018). 55. According to eminent Urdu critic Shamsur Rehman Faruqi, Khan Mahboob Tarzi wrote several SF novels in Urdu in the 1940s, including Do Diwane and Barq Paash, yet to be translated. Personal communication. 56. Kylas Chunder Dutt, ‘A Journal of Forty-Eight Hours of the Year 1945’, 1835, reprinted in Shoshee Chunder Dutt, Selections from ‘Bengaliana’, ed. Alex Tickell, Nottingham: Trent Editions, 2005, 149-159. Also,https:// en.wikisource.org/wiki/Index:A_Journal_of_Forty-Eight_Hours_of_the_ Year_1945.djvu (accessed 25 May 2018). 57. Alex Tickell suggests that these writings about imagined rebellions exploit a degree of sanctioned dissent in the pre-1857 period. See Tickell, ‘Introduction’, in Dutt, Selections from ‘Bengaliana’, 19. Also see Meenakshi Mukherjee’s discussion of the relative openness of the English press at the time, in Perishable Empire : Essays on Indian Writing in English, 53–54. 58. Shoshee Chunder Dutt, ‘The Republic of Orissa: A Page from the Annals of the 20th Century’, 1845, reprinted in Dutt, Selections from ‘Bengaliana’, 141–48. Dutt was twenty-one when his piece appeared in The Saturday Evening Harakuru (25 May 1845). See Mukherjee, Perishable Empire, 52–53. 59. See Khan, ‘Editorial’, based on his own doctoral work on SF in India. Also see Shoshee Chunder Dutt, Selections from ‘Bengaliana’, ed. Alex Tickell, Nottingham: Trent Editions, 2005, esp. 141–59. These stories by Kylas Chander Dutt and Shoshee Chunder Dutt are described as the earliest extant narrative texts by Indians writing in English by Meenakshi Mukherjee in The Perishable Empire: Essays on Indian Writing in English, 2000, reprinted, New Delhi: OUP, 2002, 52. For the text of Hussain’s short story, originally published in The Indian Ladies’ Magazine, Madras, 1905, in English, see http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/sultana/dream/dream.html (accessed 17 February 2018). 60. See Suparno Banerjee, ‘Other Tomorrows’, esp. 33–39. 61. Ibid., 201–03. It is likely that similarly sceptical and self-critical work has begun to appear more often in SF written in the bhashas/vernacular languages, since liberalization and its discontents (especially from 1991 onwards) left its imprint; further research into this question is needed. Mahasweta Devi’s Bengali story ‘Pterodactyl, Pirtha, and Puran Sahay’ makes a passionate critique of developmental processes that marginalize tribal populations while invoking paleontology in an ironic vein. See ‘Pterodactyl, Pirtha, and Puran Sahay’, tr. Gayatri Chakravorti Spivak, in Mahasweta Devi, Imaginary Maps: Three Stories, New York: Psychology Press, 1995, 95–196. 62. See Suparno Banerjee, ‘Other Tomorrows’, 201–03, and Nandy, esp. 256–58. Anil Menon is more sanguine about regional SF, though he too acknowledges its paucity and limitations. See Menon, ‘On Hunting a Snark: On the Trail of Regional Science Fiction’, at http://www.literaturaprospectiva.com/wp-content/uploads/ snark-juan.pdf (accessed 15 December 2017). 63. Bal Phondke, ed., It Happened Tomorrow, New Delhi: National Book Trust, 1993, esp. ‘Preface’, ix–xxii. 64.Shubhada Gogate’s Marathi story in translation ‘Birthright’ is an example of this, with its nightmarish vision of the brainwashing of unborn children in statecontrolled Foetus Development Centres. ‘Birthright’, Phondke, ed., It Happened Tomorrow, 100–29. 65. ‘Preface’, Phondke, ed., It Happened Tomorrow, xx. Also see, Banerjee, ‘Other Tomorrows’, 49, 26. 66. http://www.sociologydiscussion.com/science/genesis-of-people-sciencemovement-explained/851, accessed Jan. 23, 2019. 67. In Bal Phondke’s periodization of the history of SF, an initial emphasis on adventure in the first stage (Shelley and beyond) is followed by the era of pulp fiction when there was a balance struck between science and fiction, though science was sought to be propagated by and large as a result of the influence of editors like John W. Campbell. In the third stage, after the Second World War and the nuclear explosions at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, concerns about science’s potential for running amok came to the fore and social concerns began to predominate. In the fourth stage, questions of form and style became important as the aesthetic dimension superseded the purely scientific. In Phondke’s assessment (1993), Indian SF evolved through similar stages, with translations of H.G. Wells, Jules Verne and other SF authors becoming popular at first. Most Indian SF in his view belongs to the second or third stages. Needless to say, even for its time this schema was an oversimplification. Phondke, ‘Preface’, xiii–xviii. Also see, Banerjee ‘Other Tomorrows’, 49–53. 68.See ‘Preface’ Phondke, ed., in It Happened Tomorrow, xvi–xxi, where he flags ‘Tareche Hasya’ by S.B. Ranade, an early Marathi SF story of the nineteenth century, as well as adult-oriented SF in Marathi that began to appear in the 1960s and 1970s, with the support of the journal Naval, edited by Anant Antarkar, further strengthened by the contributions of Jayant Narlikar. Also see the reference to ‘Brachatiyar Desh’, the first Asomiya SF story by Hariprasad Baruah, which appeared in 1937, in Dinesh Chandra Goswami, ‘Science Fiction and Fantasy in Indian Writing’, unpublished paper, presented at the Sahitya Akademi, Seminar on Contemporary Story Writing in India and Iran, 25 November 2016. Goswami has a story about surrogacy in the Indian context, ‘Half a Help’ in Dinesh Chandra Goswami, The Hair Timer: An Anthology of Science Fiction Stories, tr. Amrit Jyoti Mahanta, New Delhi: NBT, 2011, 159–70. 69. 70. 69. Anil Menon, ‘On Hunting a Snark: On the Trail of Regional Science Fiction’, at http://www.literaturaprospectiva.com/wp-content/uploads/snark-juan.pdf (accessed 15 December, 2017). 70. For an interesting recent initiative discussing issues relating to Indian genre fiction in seven languages, Tamil, Urdu, Bangla, Hindi, Odiya, and Marathi, in addition to English, see Bodhisattva Chattopadhyaya et al’s ‘Introduction’, https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Bodhisattva_ Chattopadhyay/publication/326416187_Indian_genre_fiction_languages_ literatures_classifications/links/5b4c6f65a6fdccadaecf70bb/Indian-genre-fictionlanguages-literatures-classifications.pdf (accessed 11 November 2018). 71. For an instance of Orientalist futurism, see Jan Lars Jensen’s Shiva 3000 (London: Pan, 1999). British writer Ian McDonald’s SF based in a future India is more empathetic and moves beyond simplistic stereotypes. See, for instance, Ian McDonald, Cyberabad Days, London: Gollancz, 2009. Ian McDonald’s earlier novel, River of Gods, 2004, reprinted London: Gollancz, 2009, is more problematic and marred by backpacker clichés about India and its varied spectacles. For critical analysis, see Banerjee, ‘Other Tomorrows’, 35–48, 167–77, 209. 72.The Indian Constitution was amended by 42nd Constitutional Amendment Act, 1976 by which an Article 51A was inserted making provisions for the Fundamental Duties prescribed for citizens of India, including the duty ‘to develop the scientific temper, humanism and the spirit of inquiry and reform’. See https://www.quora.com/Is-the-Indian-constitution-the-only-constitution-in-the-world-that-talks-about-developing-scientific-temper (accessed 23 January, 2019). 73. Shiv Viswanathan, ‘Foreword’ in Kothari and Joy, eds., Alternative Futures, vii. He also cites the work of Meghnad Saha and the Science and Culture group, which saw the dangers of synthetic chemistry and sought alternatives to protect primary products like lac and indigo. Viswanathan, ‘Foreword’, viii. For an extended account of radical ecological democracy, see Aseem Shrivastava and Ashish Kothari, Churning the Earth: The Making of Global India, New Delhi: Viking Penguin, 2012, esp. 293–308. Also see Gandhi’s speech to a gathering of Asians (the Inter-Asian Relations Conference, organized by the Indian National Congress before independence) in April 1947, even as the Partition carnage was taking place, for a vision of a collective Asian future, http://www.gandhi-manibhavan.org/gandhicomesalive/speech7.htm (accessed 1 February 2018). An ironic projection of Gandhian ideals into the future appears in Manjula Padmanabhan’s short story ‘Gandhi-Toxin’ in Kleptomania: Ten Stories, New Delhi: Penguin Books India, 2004, 91–98. 74. Viswanathan, ‘Foreword’ in Kothari and Joy, eds., vii. 75. See Ramchandra Guha, Environmentalism: A Global History, New Delhi: OUP, 2000. 76. As eminent sociologist and thinker J.P.S. Uberoi put it in his seminal study, advocating a rethink of modern knowledge systems from a Gandhian perspective, ‘…modern Western science at some time took the wrong direction in the intrinsic sense…its findings, theories and techniques in all its branches are largely untrue, misleading and senseless for mankind as a whole.’ In J.P.S. Uberoi, Science and Culture, Delhi: OUP, 1978, 16. Also see Vandana Shiva’s feminist ecological take in Staying Alive: Women, Ecology and Survival in India, New Delhi: Kali, 1988, https://archive.org/stream/StayingAlive-English-VandanaShiva/Vandana-shivastayingAlive_djvu.txt (accessed 1 February 2018); Ashis Nandy, ‘Satyajit Ray’s Secret Guide to Exquisite Murders: Creativity, Social Criticism and the Partitioning of the Self’, 237-66; and Viswanathan, ‘Foreword’, vii–xi. 77. Amitav Ghosh, The Calcutta Chromosome: A Novel of Fevers, Delirium and Discovery, New Delhi: Ravi Dayal, 1996. Also see Banerjee, ‘Other Tomorrows’, for a critical account, esp. 60–75, and the detailed discussion of the novel in Eric D. Smith’s ‘Claiming the Futures That Are, or, The Cunning of History in Amitav Ghosh’s The Calcutta Chromosome and Manjula Padmanabhan’s ‘GandhiToxin’ in Globalization, Utopia and Postcolonial Science Fiction: New Maps of Hope, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, 98–126. 78. See Jayant Narlikar’s story ‘The Ice Age Cometh’, tr. Jayant Narlikar in Phondke, ed. It Happened Tomorrow, 1–20; Fred Hoyle, The Black Cloud, 1957, reprinted, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1977; D.C. Goswami, The Hair Timer, and Sukanya Datta, Worlds Apart: Science Fiction Stories, 2012, reprinted, New Delhi: National Book Trust, 2014. 79. 80. 79. See, for instance, ‘Jillu’ in Reliving Sujatha: His Best Stories in English, tr. Vimala Balakrishnan New Delhi: Vitasta, 2017, 231–42, and Ruchir Joshi, The Last Jet-Engine Laugh, 2001, reprinted, New Delhi: Harper Collins, 2008. 80. Shiv Viswanathan, ‘Foreword’. Also see, Viswanathan, https://scroll.in/ article/809246/how-indian-science-stopped-being-fun-and-turned-into-a-formula (accessed 1 February 2018). Also see, Kothari and Joy’s imagining of an activist’s address to a Mahasangam of grassroots activists in 2100, in a world transformed by radical ecological democracy, ‘Looking Back into the Future: India, South Asia and the world in 2100’ in Ashish Kothari and K.J. Joy, eds., Alternative Futures: India Unshackled, New Delhi: UpFront Publishing, 2017, 627–45. 81.Vandana Singh, The Woman Who Thought She was a Planet, as well as Eric D. Smith’s critical response at ‘There’s No Splace Like Home: Domesticity, Difference, and the “Long Space” of Short Fiction in Vandana Singh’s The Woman Who Thought She Was a Planet’ in Smith, Globalization, Utopia and Postcolonial Science Fiction, 68–97; Vandana Singh, Ambiguity Machines and Other Stories, New Delhi: Zubaan, 2018. Also see https://www.tor.com/2019/01/14/announcingthe-nominees-for-the-2019-philip-k-dick-award/, accessed 23 January, 2019; Anil Menon, The Beast with Nine Billion Feet, New Delhi: Young Zubaan, 2009; Rimi B. Chatterji, Signal Red, New Delhi: Penguin Books India, 2005; and Priya Sarukkai Chhabria, Generation 14, New Delhi: Penguin Books India, 2008. 82.This remarkable novel is set in Toronto in the near future, at a time when it becomes possible to live lives across several generations through memory transference into recipient bodies; however, a curious case of Leaked Memory Syndrome, or Nostalgia (a malady in which reminders of past lives persist) is discovered by the narrator, a nostalgia doctor named Dr Frank Sina, which eventually leads to an investigation by the Department of Internal Security. See M.G. Vassanji, Nostalgia, New Delhi: Penguin Books India, 2016. 83. Clark Prasad, Baramulla Bomber, New Delhi: Niyogi Books, 2013, and Sami Ahmad Khan, Aliens in Delhi, New Delhi: Niyogi Books, 2016, https://worldsf. wordpress.com/2012/08/28/tuesday-fiction-electric-sonalika-by-samit-basu-authorweek-4/ (accessed 23 November 2018). Also see, http://indianexpress.com/ article/lifestyle/art-and-culture/imagine-it-isnt-hard-to-do-hugo-awards-5143031/ (accessed 20 March 2018) and http://www.eff-words.com/fiction/ (accessed 19 November 2018). For SF stories by some of these authors in online magazines, see http://strangehorizons.com/fiction/the-trees-of-my-youth-grew-tall/ (accessed 23 October 2018), https://www.tor.com/2018/08/01/loss-of-signal-sb-divya/?fbclid=IwAR1zNl jb97zOgBXaDteU02U_wGYFhv0_YqJzImxTpXzx9J75zEUjKmktoEc (accessed 23 October 2018); https://uncannymagazine.com/article/fandom-for-robots/?fbcl id=IwAR2TV77Fztudi0kq8p7kVbL-fhO0qCbgnCvx0jK4uVO5rrw4eANq4XTv0 Jw (accessed 23 October 2018, https://automatareview.com/more-tomorrow-premeemohamed?fbclid=IwAR1HmBpG-heJN-J0CI94zQTR3UMMol G6DxcnFJVJy2Pc0- ktSBqVWGq2eXo (accessed 23 October 2018), http://clarkesworldmagazine.com/das_09_12/ (accessed 23 October 2018). 84. In historian Mukul Kesavan’s novel Looking through Glass, the narrator finds himself inexplicably transported to the 1940s, with an awareness of the destructive impact of the looming Partition. See Mukul Kesavan, Looking through Glass, New Delhi: Ravi Dayal, 1995. Also see, Anil Menon and Vandana Singh, eds., Breaking the Bow: Speculative Fiction Inspired by the Ramayana, New Delhi: Zubaan, 2012. 85. 86. 85. See, for instance, Anil Menon, Half of What I Say, New Delhi: Bloomsbury, 2015, and Vandana Singh’s SF story in tribute to Premendra Mitra, ‘Conservation Laws’ in Singh, The Woman Who Thought She was a Planet, 109–29. Also see Vandana Singh’s collection of speculative stories, Ambiguity Machines and Other Stories. On the history of South Asian speculative fiction, see Mimi Mondal’s article at https://www.tor.com/2018/01/30/a-short-history-of-south-asianspeculative-fiction-part-i/ (accessed 3 February 2018). The influence of SF can be seen in other domains, such as the performing arts, as seen in Raqs Media Collective’s The Return of Tipoo’s Tiger (2017), in which Tipoo Sultan’s tiger (an automaton depicting a tiger devouring a British soldier, now to be found in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London) is the sole relic surviving from European culture of this era many centuries hence, even as its significance is sought to be retrospectively reconstructed, in this speculative multi-media performance piece. The Return of Tipoo’s Tiger, 2017, Performance + Installation, Videos, Ephemera, Talks and Conversations, ‘Collecting Europe’ at the Victoria & Albert Museum’s Lunchroom, Learning Centre. 86. See Randi Anderson’s account at http://www.writersdigest.com/whats-new/ speculative-poetry-know-science-fiction-fantasy-verse (accessed 18 February 2018). 87.Much of such retold mythology approximates kitsch, the degraded form of myths in which clichés and tired rhetoric are presented for instant consumption by the reader, an observation Stanislaw Lem made about much of commercially produced American SF. See Lem, ‘Science Fiction: A Hopeless Case’, 67–71. For a recent critical perspective on the ubiquity of myth in Indian genre fiction (not just SF), see Chattopadhyay et al, ‘Introduction’ at https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Bodhisattva_Chattopadhyay/publication/326416187_Indian_genre_ fiction_languages_literatures_classifications/links/5b4c6f65a6fdccadaecf70bb/ Indian-genre-fiction-languages-literatures-classifications.pdf (accessed 11 November 2018). 88. Nalo Hopkinson, ‘Introduction’, and Uppinder Mehan, ‘Final Thoughts’, in Nalo Hopkinson and Uppinder Mehan, eds., So Long Been Dreaming: Postcolonial Science Fiction and Fantasy, 2004, reprinted, Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2011, 7–11, 269–70. 89. It often seemed that the plot of Jack Finney’s The Body Snatchers (1955) was being realized in an Indian avatar, with ordinary people being transformed into unrecognizable versions of themselves via social media, baying for blood in online (and real-life) lynch-mobs. See Jack Finney, The Body Snatchers, 1955, reprinted, London: Gollancz, 2010. 90. Fredric Jameson cites Darko Suvin’s view that utopia is a subgenre of science fiction, in his ‘Introduction’, Archaeologies of the Future, xiv. For a notion of South Asia which is ‘civilisational, reciprocal and local in its diversity’, see Shiv Viswanathan, http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/talk-like-a-south-asian/ article22828352.ece (accessed 25 February 2018). 91. For a recent futurological speculation forecasting the emergence of supra-human entities using bioengineering and data-driven algorithms, see Yuval Noah Harari, Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow, 2015, tr., London: Vintage, 2017, esp. 428–62.Tarun K. Saint is an independent scholar and writer born in Kenya, and has lived in India since 1972. His research interests include the literature of the Partition and science fiction. He is the author of Witnessing Partition: Memory, History, Fiction (2010), has edited Bruised Memories: Communal Violence and the Writer (2002) and co-edited Translating Partition: Essays, Stories, Criticism (2001) with Ravi Kant. His most recent co-edited volume is Looking Back: The 1947 Partition of India, 70 Years On (2017), a collaboration with Rakhshanda Jalil and Debjani Sengupta.

Leave a Reply