Saeed Ibrahim

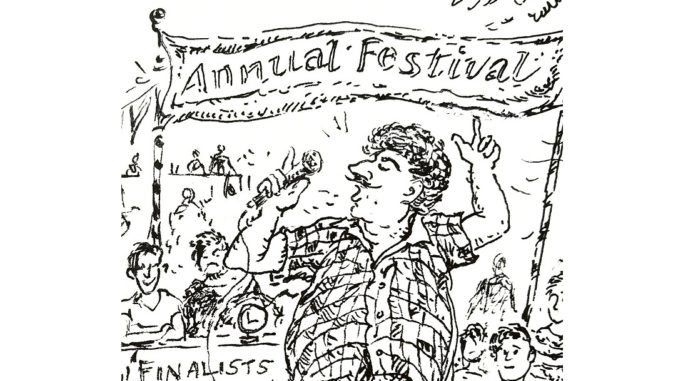

(Illustrations by Danesh Bharucha)

Jeevan looked at his face in the mirror and decided he needed a haircut. His wife had been reminding him for the past week about his overgrown locks but it had not registered. Like in most things, suggestions made by others were ignored until he himself decided that the proposed idea made sense, and then he would promptly proceed to execute it. So it was with the timing of his haircut.

He walked the short distance to his regular hair dressing saloon just a ten minute walk from his home. He was disappointed to see that there were at least two others in the queue before him but he shrugged his shoulders and decided to wait his turn. At least he would be able to catch up on his Sunday newspaper whilst he was waiting. But being used to enjoying his paper in the peace and quiet of his own home, he found the chatter in the barber’s shop disturbing. He turned around and saw that the customer being served in the chair was none other than his neighbour Suresh Babu and that the constant stream of conversation between the barber and his client was coming from this source. In fact it was more a non-stop monologue from Suresh Babu rather than a conversation. The barber added the occasional polite word of agreement out of deference for his customer in between the snip-snip sound of his flying scissors cutting and shaping Suresh Babu’s thick, woolly hair.

![]()

Today’s topic was the recent demonetisation of the Rs. 500 and Rs. 1,000 bank notes by the government and Suresh Babu was holding forth with his views on why it was a disastrous decision bringing undue hardship to the common man and not solving the problem of black money and the use of fake currency. The poor barber, ignorant of the economic fallout of the government’s move, merely nodded his head from time to time, until the lecture perforce came to an end when he had finished cutting Suresh Babu’s hair and called out, “Next please,” to summon the waiting customer.

That call unfortunately was not for Jeevan and he sat patiently waiting for his turn. Having paid the barber, Suresh Babu made towards the exit, but on spotting Jeevan came over and settled down on the seat next to him.

“Hello, how are you Jeevan? I am sorry I did not see you earlier. It is a rare chance to meet you like this. Whilst waiting your turn for a haircut, what better opportunity than to talk to you about the recently completed Assembly Elections. What do you think of the results? I don’t think the opposition put up a strong enough fight. If it was left to me, I would not have given a ticket to that unworthy candidate from our constituency. First of all he has a criminal record, and there are a number of cases of corruption lined up against him……”

Jeevan, who had no interest in politics, was in no mood to hear a lecture on the electoral results. Once he had set forth to achieve an objective or task he always liked to see it through to its completion and today he did want to have his haircut. On the other hand, how was he to endure this torture for the next twenty minutes until his turn came? Screw the haircut, he thought to himself, as he quickly made up his mind and announced, interrupting Suresh Babu in mid sentence:

“I am sorry Suresh Babu. It’s taking too long for my turn. I have some important work to attend to and I will come and have my haircut some other time.” Without waiting for Suresh Babu to respond, he quickly rushed out of the shop and made good his escape before his neighbour could follow him out and stop him.

Suresh Babu was a retired college lecturer and lived in the same apartment building as Jeevan in one of Bangalore’s middle class residential localities. He was a stocky and heavy set man of around sixty-five years with a friendly and gregarious nature, quick to strike up a conversation even with strangers. He was extremely well informed and his knowledge of current affairs was prodigious. But he loved talking and the sound of his own voice, and he often ran the risk of boring his listeners with one of his long spiels. He had a thick bushy moustache and he always preferred bush shirts to tuck-in shirts, perhaps to hide the roundness of his belly. If you passed him by, you would probably not give him a second glance. But he would not allow you to go by unnoticed for he had this habit of buttonholing you if you crossed him on the street. On seeing you, he would stop you in your tracks, hold on to your arm or sleeve and involve you in conversation or rather engage you as an unwilling audience to one of his lengthy monologues on a topic that took his fancy on that particular day.

![]()

For Suresh Babu was a compulsive talker. He would ignore your look of boredom or a stifled yawn and was unperturbed even if you looked away in utter desperation. He would just carry on non-stop. Often having exhausted a particular subject, he would connect it to another topic through a cleverly thought-out thread in order not to interrupt the continuity of his monologue. In vain you would seek an escape route and if you were unable to find one, you just stood there and suffered in silence.

Over time, Jeevan had mastered the art of avoiding him. On spotting him from afar, he would cross over to the other side of the road or time his exit from the building in order not to cross him in the lift. But there were other unsuspecting victims whose inexperience or courtesy Suresh Babu preyed on, unmindful of their lack of interest or that they may have other things to do rather than stop and listen to him.

This said, Suresh Babu, despite his peculiar habit, was in reality quite a well-meaning, friendly and harmless individual, and all the people in the community looked upon his eccentricity with indulgence and tolerance and were never offended by it. In fact in their locality there was a lot of conviviality and fellow feeling going around and the local area committee often organized events and get-togethers where the entire family was encouraged to participate. The most popular of these events was an annual festival that was held over the first weekend of June. The venue was a large school playground where stalls were set up selling home-made food items, handicrafts, toys and knick-knacks. There were also counters with games of skill and games of chance, a raffle and a lucky number dip and several rounds of Tombola. Friendly competitions were also organized for various age groups.

This year one of the competitions organized was a contest for the longest non-stop speech or talk by an individual participant on any subject of his or her choice. The rules were quite simple: the talk was to be on a single topic and the subject was not to be changed, the speaker was not allowed to pause or stop in between, not even to clear his/her throat or take a sip of water and he or she was to speak totally extempore without consulting notes. The competition was open to all residents of the local community provided they were aged18 years and above, with no upper age limit. There was to be a single prize of Rs. 2,000 for the winner and the decision of the three judges was to be final. The contestants were to be judged on both the length as well as the content of their speeches. There was to be a qualifying and eliminating round on the first day and the two finalists were to battle it out on the second and last day of the event.

When Suresh Babu heard of the contest, he was excited, and was the first one to register feeling quite confident that he would walk away with the prize, having several years of experience behind him. After all, he had not been a respected and sought after college lecturer for nothing.

There were a total of six entries received and Suresh Babu, at sixty-five, was the oldest participant. On the first day he arrived at the venue early and was quickly surrounded by a group of young boys one of whom chaffed him good-humouredly:

“Uncle, how come you are taking part? At least you should have given the younger people a chance to win.”

Another teased, “I am sure you will win Uncle. Are you going to give all of us a treat with the prize money?”

Suresh Babu brushed them aside and walked quickly towards the dais. The three judges were seated at a desk in front of the dais and the audience was a crowd of eager onlookers who stood standing in a circle around the makeshift stage. The four young college students, although they were experienced debaters and spoke well, were no match for the other two participants, Suresh Babu and a software engineer working for a well known multinational company. Two of the students got eliminated because they pulled out prepared notes and started to read from them and the other two spoke for ten and twelve minutes each. The software engineer clocked fifteen minutes, leaving Suresh Babu an easy target which he comfortably surpassed, and wrapped up his talk at twenty minutes. The two finalists congratulated each other and the session was brought to a close. The time was fixed at 4 pm for the finals the following day.

The software engineer was a twenty-eight year old youth with a muscular and athletic body, used to regular exercise. He was also an enthusiastic runner who had participated in several 10K and 15K runs in the past two years. To build up stamina and sustaining power he was well aware of the importance of fitness and self discipline. He went home that evening and spent several hours reading up and making notes on his chosen subject in preparation for the following day’s event.

Suresh Babu on the other hand was not in the best shape physically. Short and with a pot belly he had hardly ever exercised in his entire life. And unlike his young competitor, he had not felt the need for preparation. Being over confident, he relied mostly on his wide knowledge and past experience and had put his faith in a totally unscripted and spontaneous delivery of his speech. Despite his self-assurance he had felt a certain physical uneasiness the previous night. He had a feeling of indigestion and heartburn and had woken up several times to wipe a heavy sweat from his forehead and arms. He dismissed this discomfort to the excessive summer heat and went back to a fitful sleep.

The next day he arrived at the festival venue at the appointed time dressed in his Sunday best, a red and blue checked bush shirt and black trousers. Jeevan’s wife was actively involved in community affairs and she was on the organising committee for the fete. Jeevan, for want of anything better to do that Sunday afternoon, decided to amble along to the festival site. He thought maybe he would try his luck at a few rounds of Tombola. He strolled along taking a peek at the various stalls that had been set up, and finally came to the makeshift stage where the finals of the talking competition were being held. Out of curiosity and without really being a supporter of Suresh Babu, he joined the circle of onlookers.

Lots were drawn for who was going to be the first speaker, each participant having to declare at the start the topic or subject of his speech. The software engineer drew the first lot. There was a loud round of applause, as with a sprightly step he strode up to the dais. His chosen subject was “The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Today’s World” and he set off on a detailed and well researched exposition on the subject. With the aid of convincing arguments in favour of the need and relevance of AI, he ended his speech at exactly twenty-eight minutes. He bowed and stepped off the platform leaving the stage for Suresh Babu.

![]()

Suresh Babu came up to the platform and heaved himself up the two short steps of the dais. His chosen subject was “Climate Change” and he launched upon a lengthy speech explaining the causes of climate change and the steps the various countries of the world needed to take to combat its evil effects. He was well into his lecture, when without pausing, he pulled out a handkerchief from his trouser pocket as beads of sweat began to form on his forehead. He mopped his brow with a hurried movement and continued speaking. After a few minutes the sweat on his brow had formed again and he repeated the gesture. He had just launched upon the agenda of the last Climate Conference when he stole a nervous glance at his wrist watch.

A hush filled the gathered crowd. This was so unlike Suresh Babu’s usual self; he was always so self-assured and unperturbed. Confident about his speaking abilities he never bothered about the time. His watch told him that he had been speaking for twenty-two minutes already. He would need to speak for at least another seven minutes in order to overtake the record set by the previous speaker. Would he be able to keep up the effort, he asked himself?

With a surge of sheer will power he carried on, but the speed of his delivery had slackened. All of a sudden he felt a tightness in his throat and chest and with his right hand clutching at his heart, he collapsed in a heap on the stage. He had clocked twenty-three minutes and thirty-five seconds.

![]()

Jeevan, who had earlier been consciously avoiding Suresh Babu, was now torn by guilt and remorse. He, along with some other men rushed to his aid. Someone raised his head and offered him some water, another removed his shoes and loosened his clothing, whilst a third was seen desperately fanning his face. The organizers quickly summoned an ambulance and Suresh Babu was rushed to a nearby hospital. He had infact suffered a heart attack, but with timely attention his condition was soon brought under control. Several tests were conducted at the hospital and it was found that apart from a damaged heart valve, he also had hyper-tension and latent diabetes. He spent a week at the hospital, was advised a course of treatment and complete rest at home, with a cessation of all activities involving exertion and stress.

The talkathon was won by the software engineer, but as far as Suresh Babu was concerned, the event had effectively laid to rest his days as a compulsive talker.

*********

Bangalore based writer, Saeed Ibrahim, is the author of “Twin Tales from Kutcch,” a family saga set in Colonial India, which has won critical acclaim both in India and overseas since its publication last year. Saeed was educated at St. Mary’s High School and St. Xavier’s College in Mumbai, and later, at the University of the Sorbonne in Paris. His short stories are slice-of-life, character-based portraits reflecting on the various subtleties of human nature. Some are humorous and satirical pieces on the quirks and idiosyncrasies in people’s behaviour, whilst others offer surprising insights into the compassionate and humane side of human nature. His book reviews and stories have been published in newspapers and magazines such as “The Deccan Herald,” “The Beacon” and the “Bengaluru Review.”

Indo-French painter Danesh Bharucha was born in Pune, and was 21 when he moved to the South of France, where the popular Belgian artist Laurent Moonens became his mentor. Under Moonens’ tutelage, Bharucha learnt the challenges and subtleties of watercolour painting. Moving to Paris the following year, he worked for 24 years for the Voice of America and discovered his love for pen and ink sketching when he took a course in figure-drawing at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris. In France, Bharucha has exhibited at the Paris Town Hall, the American Embassy, and the Mairie de Meudon. In February and March 2018, the Alliance Française sponsored two major one-man shows of his work in Pune and Chandigarh.

Saeed Ibrahim in The Beacon “Twin Tales From Kutcch”: An extract

Such a hilarious and enjoyable read. Each of us, I am sure can look back and find a “Suresh Babu” in our past or present and relate to him.

The sketches are literally the icing on the cake, and make the story come to life.

Enjoyed the story and how skillfully you wove it.

Jeevan and poor Suresh Babu, I could literally picture the whole event!

Marianne

Extremely enjoyable and entertaining short story . A must read

And excellent illustrations by Danesh Bharucha,so apt with the story