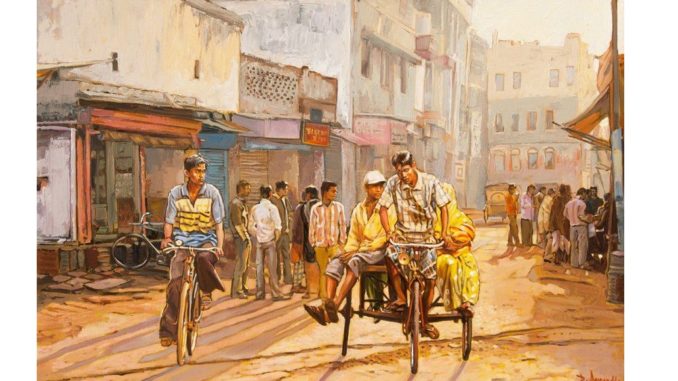

Courtesy: Pinterest

Geetanjali Shree

P

icture this. Small and not so small north Indian towns. Mother speaks Hindi. That makes Hindi literally my mother tongue! All the exchange with the so-called servants – the cook, the peon, the sweeper, the gardener, and more – is in Hindi. So also with other service attendants who land up every now and again – the tailor, the barber, the priest, the milk man, the newspaper boy. The last named brought us Hindi magazines. So we picked up some of our literary lore. The rest we had as bed-time stories from our mother.

This is within the compound of the house. Outside that stretches the town. Streets full of shops and their keepers, fruit and vegetable vendors, rickshaw pullers and tonga drivers. Sounds float in across the boundary – shouts, conversations, abuses, songs, including evocative short ditties sung loudly by itinerant vendors to lure prospective buyers. All in Hindi. Step out to their midst and we are surrounded by the choicest colloquial Hindi, resonant and varied. The music and the cadence of it turning our being!

Step out we did. Sometimes with a purpose on the street – shopping for toys, sweets, festival paraphernalia on religious dates which came non-stop – but everyday to pile into rickshaws and go to school.

School. Another world. English! Another value system. Another status. High!

These used to be Christian missionary schools – simply called ‘convents’ – and English-medium privately run ‘public’ schools. Talk English, think English, play English, pay a fine for speaking in Hindi during any but the Hindi class. In that class we were taught elementary Hindi! Just so we know what the language of ordinary masses is and can converse enough to get by for necessaries in the streets.

Hindi here, indeed, was a minority language, a dying language, an ‘illiterate’ language, and even in that period of euphoric nationalism of a newly independent country, it was given, in these centers of ‘good’ education a token respect!

But our respect for English was not token, merely snooty! We learnt conversation in a silly conventy accent and often without grammar, and were pleased to hear non-English speaking Europeans and the Americans (of course!) exclaim in admiration at our skills. We learnt insufficient and indifferent literature in any of these tongues, but for long remained pleased that we knew names of places in London. And remained uncaring that we knew not names of places in the town of our domicile!

That is how many of us have grown up: in two languages with an objectionable colonial hierarchy separating them. Unsystematic, uneven, skewed in both. Imbibing as also resisting the value system intrinsic to them.

And yet, and yet I say, that is where the minority status of one ends and the superiority demeanour of the other collapses. Still characteristic of the elites in the erstwhile colonised societies, this differential, lop-sided education in the two languages and their literatures freed at least some of us from a backlog of learning and gave us the chance of learning anew in adventurous unconventional ways either or both of these languages.

We embarked on a journey of relearning, rediscovering, reconstructing the language we chose.

It is almost by accident that one of us chooses Hindi and the other English. ‘Almost by accident’ I say, because it might not be entirely so. In some seemingly inexplicable way, the osmosis around me, the politics/economics of language and protest, the appeal of the sound of Hindi I heard, over the appaarent sophistication of the English I was taught, all must have had me ‘chosen’ by Hindi. Even though it might seem that it could equally easily have happened the other way around. And that I could, then, have done just as well or badly in English. Maybe. Maybe not.

Perhaps the look of Hindi, the tonality of it, the distance of it, which gave it an odd ‘sex appeal’ attracted me like English did not. Romance has its own mechanism and dynamics. Perhaps, to stay with the metaphor, the ‘unavailability’ of it also fascinated me. And the ‘otherness’ of it made the adrenalin level shoot up in me! The ‘other’ is known to be dangerous and invested with evil. It is also magic, uncharted territory, beautiful!

Not that English was mine and easier or more available. It only appeared more so. Most of us who studied in those English-medium schools acquired a skin-deep ‘English’ veneer and lost the language in it! Very few of us worked diligently on our skills to actually hone the language and learn its literature. Few of us became R.K. Narayans. Many of us, at a later date, could become Salman Rushdies, ‘inventing’ our own English and a colourful one too, but let those who became Englishwallahs tell that story!

Mine is the story of choosing and being chosen by Hindi to write in it and my relationship with it is still evolving.

Landed with a minority language, have I? What does it mean? Number-wise Hindi figures among the world’s top most spoken languages (being placed second only to Chinese by its partisans!). But yes, its want of a position of power in today’s global village may worry many of its adherants.

Few outside its own circle may know what is happening in Hindi. This is the sentence of sentences in the globalised today! But that many don’t know it does not mean that nothing is happening in the Hindi world, that also is the sentence of sentences in the globalised today!

That even a Salman Rushdie can be foolish enough to declare that nothing (worthwhile) is happening on the non-English Indian literary scene is a measure of the narrowness and ignorance the opening out of the world, paradoxically, has led to! One market dominates and possesses the power and resources of publicity, and knowingly/unknowingly assumes it is the only stage!

It is NOT. Nor is it the only market. Much as we talk about a uniform economy and single market, it is true only to the extent that the American/English market is economically and politically powerful.

But ‘goods’ (here literature) are not just produced by and for it. Nor do those other goods get their life force from it.

Let me ramble on a bit more with my thoughts. The analogy in my mind is bio-diversity which makes for a healthy eco-system. Surely so too with art, literature and culture?

There are three aspects to consider in this eco-system: one, the existence of many markets/centres/ stages; two, many thriving cultures to enrich these centres; three, unevenness in economy. Polity, literacy in the vast space called India, which – mercifully – still lets plurality thrive like perhaps it cannot in the more uniform economy, polity and literacy situation of the ‘West’, if you like the ‘North’. A funny case of India’s two weak points – its size and ‘backwardness’ – turning into advantages!!)

To elaborate a little more, this is the centre, Hindi is the centre, I am a centre. And mind you, this is not a frogs-in-the-well syndrome. It is a centre, if you will, in which we Hindiwallahs congregate, create, network, and also interact with that other centre which has the self-image of being THE centre. That centre is more in the habit of ignoring or/and missing out on other centres. Yet, one way or another (translation, media, anthropology, orality) there is interaction amongst the centres. We are influenced by them, but they are also influenced by us. And so much the richer for it, all of us!

There is no need for martyrdom and self-glorification here. This is how the world and people always operate. At different historical junctures different areas/cultures/languages sit in different power positions. Just watch where Hindi – and Chinese – might not be tomorrow. French and German, alas, are not where they were yesterday.

However, it is not ‘centrality’ that is crucial to the production of art and literature. Not yet at any rate. Crucial to art and literature is life and living in that language. Which Hindi has. Not because of initiatives from the top which fund it and prop it up in the global circuits, but because organically, it throbs in small towns and villages and cosmopolitan areas.

It is this market, a market of exchange not in money and certainly not in dollars (!) which is crucial to the existence, propagation and richness of a literature. While this ‘market’ exists, people will continue to write in Hindi. They will take from – and give – it vibrancy.

Hindi, in fact, is an amazingly vibrant language and has a very active, varied literature. Fed by at least 45 dialects – though, let it be admitted, they are on the wane courtesy larger market forces – and happily borrowing from whatever tongue it comes into contact with, it is rich and eclectic. (Maybe that is why it is so well suited to writers like me, who are born of an impure, hybrid, pluralistic moment!) Comparable eminently, I think, to English which gets its hues and shades from adoption by the Irish, Chinese, African, Scottish, Indians of course, and from its own internal regional variants.

Where Hindi scores over English is that by virtue of the latter being, the language of the high and formally educated and economically privileged, those Indians writing in it – English – come from a similar class and experience (I should be careful and not stretch this fact beyond a point lest I replicate Salman Rushdie’s error, albeit from this side!) and that sets the parameters of the literature produced. Exile and nostalgia for the exotic homeland being the big, big variables in it.

The multitudinous economic, social, educational situations of those writing in Hindi and, I suspect, in other non-English Indian languages – we claim English as one of our national languages – make for multitudinous lineages and experiences. So many Hindis, consequently, emerge. Belonging to the largest human mass in north India, a mass riven with differences, the expression and construction of Hindi follow such varied routes.

Today, almost anyone who is able to learn the basic skill of writing begins to write, so urgent is the need to express and create. Tribes (so-called), Dalits, women bring into their work their own special sounds, smells, traditions, tribulations.

Someone said to me: ‘I want a renaissance in this country.’ I dare say there is a renaissance in this country. ONLY it is not brought under the same canopy, into the same market, to make of it a single powerhouse. Instead, it glows here and glimmers there, and darts and shines and sparkles elsewhere, while in between spreads the ‘darkness’ from the ‘dream’ called globalisation, which projects the self-image of promoting tolerance and plurality and equality, but in fact threatens to subsume all under a uniform sensibility often called radical and secular and modern.

When that succeeds, if it succeeds, our minds will have changed. That is when Hindi – using it now as a metaphor for other flourishing ‘minority’ languages – will be marginalised and finished. Finished not in the sense of becoming a dead language. Hindi, as also those other languages, will technically remain in use. Its vocabulary will stay pretty much as it is now. So also, more or less undisturbed, its syntax. But the sensibility will come from you know where.

In the meantime there will be those, like me, who write happily and NATURALLY in Hindi and find their readers and community within and without. If Hindi is not read more than it is, it is because it lags behind in modern networking. Just as English is read as much as it is because of its economic/political resources and market networking.

And because of the visibility it brings. No wonder a ‘two-day old writer’ in English shares the dais with all time Hindi greats, time and again.

But why go on and on about such things? Power intrudes everywhere. Here too. What is required is to work on your own routes. And roots!

Today I am a reasonably known Hindi writer. Not so long ago, on meeting me and being told I wrote, it was assumed I must be working in English. Hindi? Eyes would pop out in wonder, wanting to pin on me a badge of courage. Writing in a losing language? Writing from where the journey to ‘centre stage’ is longer?

I write for relish and quite naturally. When I started some two decades ago, the two languages – Hindi and English – were entangled within me; a colonial legacy. My early drafts show English words and even paragraphs where my Hindi vocabulary beat me and I let English carry on the flow. What is more, even my Hindi was sometimes a translation from the English and my syntax was often English.

I learnt on the job. As many in India do. You get the licence first and learn through practice afterwards. The driver, the engineer, the doctor, all kill a few and then become experts! Thankfully I killed no one. Except, some might say, the language!

But I will I say I infused into it new blood by using it my way. I should not pretend that there was no internal resistance, no received conventions to surmount. A senior Hindi writer once ticked me off about randomly coupling words There is something called shabda-maitri (friendship between words), he intoned, and only two friendly words make a couple. It was a relaxed evening and there were drinks and I was young and enthusiastic. I pointed out to him, a little too pesky perhaps, his clothes – a pair of western style trousers with an Indian style kurta or shirt! That is my generation and moment, I said, and we look good. Sound good too.

No frivolous comment alone that. Me and my kind – we relearnt our language and literature, unconventionally, incompletely, adventurously. English skips alongside me. And, still, sometimes I am the one skipping beside it! Dragged along, tug tug, hurt hurt…! But mostly I can swish it back where it belongs. Today, I am confident of using Hindi well and in new ways. Even translating from one tongue to another and coupling unlikely partners is working for us with élan. If there is impurity in my language, that is a maxim I am ready to live by, swear by.

That is how I have gone on. Disentangling from the power of English, breezing into the arms of Hindi, building with it a deeper relationship, being a ‘minority’, but trying to find our different routes to visibility, audibility, peoples, markets.

BUT

Not feeling persecuted! Or at least not more than creative writers might feel, by virtue of their vocation being marginalised, oppositional, loner beings.

And how I hope the absence of that kind of sense of persecution does not disqualify me from belonging with the likes of The Beacon! In fact, it is precisely such forums that facilitate our negotiations against the One Centralised Power.

In fact, if I am kept out of here, at long last, I will feel a minority and persecuted!!

*******

Geetanjali Shree has written five novels – Mai, Hamara Sheher Us Baras, Tirohit, Khali Jagah and Ret Samadhi – and five anthologies of short stories in Hindi. She has also written Between Two Worlds: An Intellectual Biography of Premchand in English. Her stories and novels have been translated into French, German, English ,Urdu, Polish, Serbian and Japanese as well as in other Indian languages. She has received various awards for her contribution to Hindi literature and has been invited for many reading tours and residencies in countries such as the UK, France, Switzerland, Germany, Japan, Iceland, Korea, and of course in India. The English translation of Mai won the Sahitya Academy Award. Shree ‘s sixth novel titled Sah-sa is due shortly. Apart from her fiction in Hindi, her choice of language for literary expression, Shree also writes scripts for theatre, mainly with the group Vivadi, which is based in Delhi and of which she is a founding member. Her own writings too have been adapted for the stage by distinguished directors at the NSD. She writes essays in English and Hindi for various publications. She lives in New Delhi, India

Geetanjali Shree in The Beacon Excerpt from Tomb of Sand/Ret Samadhi: Geetanjali Shree Earthworms and Masks: Arcadian Driftwood

Leave a Reply