Ismat Chugtai

{Translated from Urdu by M. Asaduddin)

IN WINTER when I put a quilt over myself its shadows on the wall seem to sway like an elephant. That sets my mind racing into the labyrinth of times past. Memories come crowding in.

Sorry. I’m not going to regale you with any romantic tale about my own quilt. It’s hardly a subject for romance. It seems to me that the blanket, though less comfortable, does not cast shadows as terrifying as the quilt, dancing on the wall.

I was then a small girl and fought all day with my brothers and their friends. Often I wondered why the hell I was so aggressive. At my age my other sisters were busy drawing admirers while I fought with any boy or girl I ran into!

This was why when my mother went to Agra she left me with an adopted sister of hers for about a week. She knew well that there was no one in that house, not even a mouse with which I could get into a fight. It was severe punishment for me! So Amma left me with Begum Jaan, the same lady whose quilt is etched in my memory like the scar left by a blacksmith’s brand. Her poor parents agreed to marry her off to the Nawab who was of ‘ripe years’ because he was very virtuous. No one had ever seen a nautch girl or prostitute in his house. He had performed Haj and helped several others to do it.

He, however, had a strange hobby. Some people are crazy enough to cultivate interests like breeding pigeons and watching cockfights. Nawab Saheb had contempt for such disgusting sports. He kept an open house for students—young, fair and slender-waisted boys whose expenses were borne by him.

Having married Begum Jaan he tucked her away in the house with his other possessions and promptly forgot her. The frail, beautiful Begum wasted away in anguished loneliness.

One did not know when Begum Jaan’s life began— whether it was when she committed the mistake of being born or when she came to the Nawab’s house as his bride, climbed the four-poster bed and started counting her days. Or was it when she watched through the drawing room door the increasing number of firm-calved, supple- waisted boys and delicacies begin to come for them from the kitchen! Begum Jaan would have glimpses of them in their perfumed, flimsy shirts and feel as though she was being raked over burning embers!

Or did it start when she gave up on amulets, talismans, black magic and other ways of retaining the love of her straying husband? She arranged for night long reading of the scripture but in vain. One cannot draw blood from a stone. The Nawab didn’t budge an inch. Begum Jaan was heart- broken and turned to books. But she didn’t get relief. Romantic novels and sentimental verse depressed her even more. She began to pass sleepless nights yearning for a love that had never been.

She felt like throwing all her clothes into the oven. One dresses up to impress people. Now, the Nawab didn’t have a moment to spare. He was too busy chasing the gossamer shirts, nor did he allow her to go out. Relatives, however, would come for visits and would stay for months while she remained a prisoner in the house. These relatives, free-loaders all, made her blood boil. They helped themselves to rich food and got warm stuff made for themselves while she stiffened with cold despite the new cotton in her quilt. As she tossed and turned, her quilt made newer shapes on the wall but none of them held promise of life for her. Then why must one live? …such a life as Begum Jaan was destined to live. But then she started living and lived her life to the full.

It was Rabbu who rescued her from the fall.

Soon her thin body began to fill out. Her cheeks began to glow and she blossomed in beauty. It was a special oil massage that brought life back to the half-dead Begum Jaan. Sorry, you won’t find the recipe for this oil even in the most exclusive magazines.

When I first saw Begum Jaan she was around forty. She looked a picture of grandeur, reclining on the couch. Rabbu sat against her back, massaging her waist. A purple shawl covered her feet as she sat in regal splendour, a veritable Maharani. I was fascinated by her looks and felt like sitting by her for hours, just adoring her. Her complexion was marble white without a speck of ruddiness. Her hair was black and always bathed in oil. I had never seen the parting of her hair crooked, nor a single hair out of place. Her eyes were black and the elegantly-plucked eyebrows seemed like two bows spreading over the demure eyes. Her eyelids were heavy and eyelashes dense. However, the most fascinating part of her face were her lips—usually dyed in lipstick and with a mere trace of down on her upper lip. Long hair covered her temples. Sometimes her face seemed to change shape under my gaze and looked as though it were the face of a young boy…

Her skin was also white and smooth and seemed as though someone had stitched it tightly over her body. When she stretched her legs for the massage I stole a glance at their sheen, enraptured. She was very tall and the ample flesh on her body made her look stately and magnificent. Her hands were large and smooth, her waist exquisitely formed. Rabbu used to massage her back for hours together. It was as though getting the massage was one of the basic necessities of life. Rather—more important than life’s necessities.

Rabbu had no other household duties. Perched on the couch she was always massaging some part of her body or the other. At times I could hardly bear it— the sight of Rabbu massaging or rubbing at all hours. Speaking for myself, if anyone were to touch my body so often I would certainly rot to death.

Even this daily massaging was not enough. On the days she took a bath, she would massage the Begum’s body with a variety of oils and pastes for two hours. And she would massage with such vigour that even imagining it made me sick. The doors would be closed, the braziers would be lit and then the session began. Usually Rabbu was the only person allowed to remain inside on such occasions. Other maids handed over the necessary things at the door, muttering disapproval.

In fact—Begum Jaan was afflicted with a persistent itch. Despite using all the oils and balms the itch remained stubbornly there. Doctors and hakims pronounced that nothing was wrong, the skin was unblemished. It could be an infection under the skin. “These doctors are crazy… There’s nothing wrong with you. It’s just the heat of the body,” Rabbu would say, smiling while she gazed at Begum Jaan dreamily.

Rabbu! She was as dark as Begum Jaan was fair, as purple as the other one was white. She seemed to glow like heated iron. Her face was scarred by small- pox. She was short, stocky and had a small paunch. Her hands were small but agile, her large, swollen lips were always wet. A strange, sickening stench exuded from her body. And her tiny, puffy hands moved dexterously over Begum Jaan’s body—now at her waist, now at her hips, then sliding down her thighs and dashing to her ankles. Whenever I sat by Begum Jaan my eyes would remain glued to those roving hands.

All through the year Begum Jaan would wear Hyderbadi jaali karga kurtas, white and billowing, and brightly coloured pyjamas. And even if it was warm and the fan was on, she would cover herself with a light shawl. She loved winter. I, too, liked to be at her house in that season. She rarely moved out. Lying on the carpet she would munch dry fruits as Rabbu rubbed her back. The other maids were jealous of Rabbu. The witch! She ate, sat and even slept with Begum Jaan! Rabbu and Begum Jaan were the subject of their gossip during leisure hours. Someone would mention their name and the whole group would burst into loud guffaws. What juicy stories they made up about them! Begum Jaan was oblivious to all this, cut off as she was from the world outside. Her existence was centred on herself and her itch.

I have already mentioned that I was very young at that time and was in love with Begum Jaan. She, too, was fond of me. When Amma decided to go to Agra, she left me with Begum Jaan for a week. She knew that left alone in the house I would fight with my brothers or roam around. The arrangement pleased both Begum Jaan and me.

After all she was Amma’s adopted sister! Now the question was— where would I sleep? In Begum Jaan’s room, naturally. A small bed was placed alongside hers. Till ten or eleven at night we chatted and played “Chance.” Then I went to bed. Rabbu was still rubbing her back as I fell asleep. “Ugly woman!” I thought. I woke up at night and was scared. It was pitch dark and Begum Jaan’s quilt was shaking vigorously as though an elephant was struggling inside.

“Begum Jaan…,” I could barely form the words out of fear. The elephant stopped shaking and the quilt came down.

“What’s it? Get back to sleep.” Begum Jaan’s voice seemed to come from somewhere.

“I’m scared,” I whimpered.

“Get back to sleep. What’s there to be scared of? Recite the Ayatul kursi.”*

“All right…” I began to recite the prayer but each time I reached ya lamu ma bain… I forgot the lines though I knew the entire ayat by heart.

“May I come to you, Begum Jaan?”

“No, child… Get back to sleep.” Her tone was rather abrupt. Then I heard two people whispering. Oh God, who was this other person? I was really afraid.

“Begum Jaan… I think there’s a thief in the room.”

“Go to sleep, child… There’s no thief,” this was Rabbu’s voice. I drew the quilt over my face and fell asleep.

By morning I had totally forgotten the terrifying scene enacted at night. I have always been superstitious—night fears, sleep- walking and sleep-talking were daily occurrences in my childhood. Everyone used to say that I was possessed by evil spirits. So the incident slipped from my memory. The quilt looked perfectly innocent in the morning.

But the following night I woke up again and heard Begum Jaan and Rabbu arguing in a subdued tone. I could not hear what they were saying and what was the upshot of the tiff but I heard Rabbu crying. the tiff but I heard Rabbu crying.

Then came the slurping sound of a cat licking a plate… I was scared and got back to sleep.

The next day Rabbu went to see her son, an irascible young man. Begum Jaan had done a lot to help him out—bought him a shop, got him a job in the village. But nothing really pleased him. He stayed with Nawab Saheb for some time, who got him new clothes and other gifts; but he ran away for no good reason and never came back, even to see Rabbu…

Rabbu had gone to a relative’s house to see him. Begum Jaan was reluctant to let her go but realised that Rabbu was helpless. So she didn’t prevent her from going.

Also read : The Midnight Knock at 4 pm: Ismat Chugtai’s ‘Lihaaf’ Trial

All through the day Begum Jaan was out of her element. Her body ached at every joint, but she couldn’t bear anyone’s touch. She didn’t eat anything and kept moping in the bed the whole day. “Shall I rub your back, Begum Jaan…?” I asked zestfully as I shuffled the deck of cards. She began to peer at me.

“Shall I, really?” I put away the cards and began to rub her back while Begum Jaan lay there quietly. Rabbu was due to return the next day… but she didn’t. Begum Jaan grew more and more irritable. She drank cup after cup of tea and her head began to ache.

I again began rubbing her back which was smooth as the top of a table. I rubbed gently and was happy to be of some use to her.

“A little harder… open the straps,” Begum Jaan said.

“Here… a little below the shoulder… that’s right… Ah! what pleasure…” She expressed her satisfaction between sensuous breaths. “A little further…,” Begum Jaan instructed though her hands could easily reach that spot. But she wanted me to stroke it. How proud I felt! “Here… oh, oh, you’re tickling me… Ah!” She smiled. I chatted away as I continued to massage her.

“I’ll send you to the market tomorrow… What do you want?

…A doll that sleeps or wakes up as you want?”

“No, Begum Jaan… I don’t want dolls… Do you think I’m still a child?”

“So you’re an old woman then,” she laughed. “If not a doll I’ll get you a babua*… Dress it up yourself. I’ll give you a lot of rags. Okay?”

“Okay,” I answered.

“Here,” She would take my hand and place it where it itched and I, lost in the thought of the babua, kept on scratching her listlessly while she talked.

“Listen… you need some more frocks. I’ll send for the tailor tomorrow and ask him to make new ones for you. Your mother has left some dress material.”

“I don’t want that red material… It looks so cheap,” I was chattering, oblivious of where my hands travelled. Begum Jaan lay still… Oh God! I jerked my hand away.

“Hey girl, watch where your hands are… You hurt my ribs.” Begum Jaan smiled mischievously. I was embarrassed.

“Come here and lie down beside me…” She made me lie down with my head on her arm “How skinny you are… your ribs are coming out.” She began counting my ribs.

I tried to protest.

“Come on, I’m not going to eat you up. How tight this sweater is! And you don’t have a warm vest on.” I felt very uncomfortable.

“How many ribs does one have?” She changed the topic.

“Nine on one side, ten on the other,” I blurted out my school hygiene, rather incoherently.

“Take away your hand… Let’s see… one, two, three…”

I wanted to run away, but she held me tightly. I tried to wriggle out and Begum Jaan began to laugh loudly. To this day whenever I am reminded of her face at that moment I feel jittery. Her eyelids had drooped, her upper lip showed a black shadow and tiny beads of sweat sparkled on her lips and nose despite the cold. Her hands were cold like ice but clammy as though the skin had been stripped off. She had put away the shawl and in the fine karga kurta her body shone like a ball of dough. The heavy gold buttons of the kurta were open and swinging to one side.

It was evening and the room was getting enveloped in darkness. A strange fright overwhelmed me. Begum Jaan’s deep-set eyes focused on me and I felt like crying. She was pressing me as though I were a clay doll and the odour of her warm body made me almost throw up. But she was like one possessed. I could neither scream nor cry.

After some time she stopped and lay back exhausted. She was breathing heavily and her face looked pale and dull. I thought she was going to die and rushed out of the room…

Thank God Rabbu returned that night. Scared, I went to bed rather early and pulled the quilt over me. But sleep evaded me for hours.

Amma was taking so long to return from Agra! I had got so terrified of Begum Jaan that I spent the whole day in the company of maids. I felt too nervous to step into her room. What could I have said to anyone? That I was afraid of Begum Jaan? Begum Jaan who was so attached to me?

That day Rabbu and Begum Jaan had a tiff again. This did not augur well for me because Begum Jaan’s thoughts were immediately directed towards me. She realised that I was wandering outdoors in the cold and might die of pneumonia! “Child, do you want to put me to shame in public? If something should happen to you, it’ll be a disaster.” She made me sit beside her as she washed her face and hands in the water basin. Tea was set on a tripod next to her.

“Make tea, please… and give me a cup,” she said as she wiped her face with a towel. “I’ll change in the meanwhile.”

I took tea while she dressed. During her body massage she sent for me repeatedly. I went in, keeping my face turned away and ran out after doing the errand. When she changed her dress I began to feel jittery. Turning my face away from her I sipped my tea.

My heart yearned in anguish for Amma. This punishment was much more severe than I deserved for fighting with my brothers. Amma always disliked my playing with boys. Now tell me, are they man-eaters that they would eat up her darling? And who are the boys? My own brothers and their puny, little friends! She was a believer in strict segregation for women. And Begum Jaan here was more terrifying than all the loafers of the world. Left to myself, I would have run out to the street— even further away! But I was helpless and had to stay there much against my wish.

Begum Jaan had decked herself up elaborately and perfumed herself with the warm scent of attars. Then she began to shower me with affection. “I want to go home,” was my answer to all her suggestions. Then I started crying.

“There, there… come near me… I’ll take you to the market today. Okay?”

But I kept up the refrain of going home. All the toys and sweets of the world had no interest for me.

“Your brothers will bash you up, you witch,” She tapped me affectionately on my cheek.

“Let them.”

“Raw mangoes are sour to taste, Begum Jaan,” hissed Rabbu, burning with jealousy.

Then Begum Jaan had a fit. The gold necklace she had offered me moments ago flew into pieces. The muslin net dupatta was torn to shreds. And her hair-parting which was never crooked was a tangled mess.

“Oh! Oh! Oh!” She screamed between spasms. I ran out.

Begum Jaan regained her senses after much fuss and ministrations. When I peered into the room on tiptoe, I saw Rabbu rubbing her body, nestling against her waist.

“Take off your shoes,” Rabbu said while stroking Begum Jaan’s ribs. Mouse-like, I snuggled into my quilt.

There was a peculiar noise again. In the dark Begum Jaan’s quilt was once again swaying like an elephant. “Allah! Ah!…” I moaned in a feeble voice. The elephant inside the quilt heaved up and then sat down. I was mute. The elephant started to sway again. I was scared stiff. However, I had resolved to switch on the light that night, come what may. The elephant started fluttering once again and it seemed as though it was trying to squat. There was sound of someone smacking her lips, as though savouring a tasty pickle. Now I understood! Begum Jaan had not eaten anything the whole day. And Rabbu, the witch, was a notorious glutton. She must be polishing off some goodies. Flaring my nostrils I scented the air. There was only the smell of attar, sandalwood and henna, nothing else.

Once again the quilt started swinging. I tried to lie down still but the quilt began to assume such grotesque shapes that I was thoroughly shaken. It seemed as though a large frog was inflating itself noisily and was about to leap on me.

“Aa… Ammi…” I whimpered courageously. No one paid any heed. The quilt crept into my brain and began to grow larger. I stretched my leg nervously to the other side of the bed to grope for the switch and turned it on. The elephant somersaulted inside the quilt which deflated immediately. During the somer- sault the corner of the quilt rose by almost a foot…

Good God! I gasped and plunged into my bed.

*******

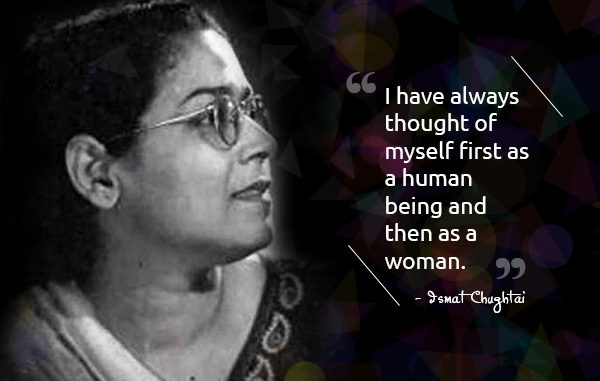

Notes -The Beacon wishes to thank M. Asaduddin for permission to reproduce this translation.Ismat Chugtai (1915-1991) was a fierce writer who really needs no introduction. Fiercely independent, an early votary of feminine agency she was often referred to as the 'Grande Dame of Urdu fiction', championing free speech and women empowerment. Her outspoken nature marked her out as an early feminist with her writings on sexuality, class conflict, and femininity. Chughtai wrote for many publications in Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, and after the heat and dust of the Lahore trial in the early 1940s where she was refused to cave in to pressure to apologise for her story, Lihaaf, she would go on to win acclaim. Lihaaf would become hugely popular; her other creatibe works are Gainda, Intikhab, Terhi Lakeer, Garam Hawa, among a host of others.

M. Asaduddin is Professor of English and Advisor to the Vice-Chancellor, Jamia Milia Islamia, New Delhi. Among other writings he has translated Ismat Chugtai’s autobiography, A Life in Words Memoirs. He has also translated and edited four volumes of the complete stories of Premchand.

Leave a Reply