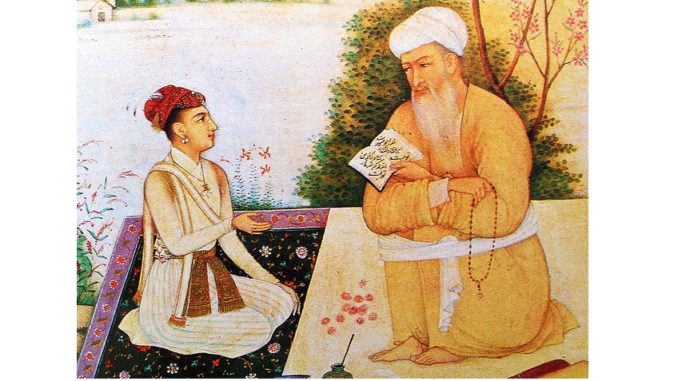

Dara Shikoh with Mian Mir sufii saint

Shamsur Rahman Faruqi

I

t is a matter of gratification and in fact, an occasion to celebrate, that the Anjuman, now concluding the first decade after the centenary of its founding in 1903, has chosen to remember Dara Shikoh as we approach the 400th birth centenary of this great man, who might also have become known as a Great Mughal, had he survived and succeeded to the throne.

Dara Shikoh was born (March 20, 1615) a most privileged baby, if not in the world, certainly in the vast lands of Hind, Sind and the Deccan shortly to be ruled by his father, the mighty Shahjahan. Born on the bank of Anasagar, in Ajmer—both lake and city revered by king and commoner because of their association with Mu’inuddin Chishti, then as now India’s most well-loved Muslim saint, he lived a comparatively protected life until about the time of his death. In contrast, Aurangzeb who defeated Dara in the wars of succession—such wars being routine among the Mughals—and then had him killed, friendless and humiliated, had always been a man well versed in the arts of battle and war.

Kishan Chand Ikhlas quotes the following line of verse as the chronogram composed on Dara Shikoh’s birth:

The first rose in the Royal Rose-Garden

This would suggest that he was seen by some, if not all, as destined to succeed his father Prince Khurram to the Empire, even though Khurram wasn’t himself King at that time and it would be another twelve years before he sat on his father Jahangir’s throne.

When Dara Shikoh died (August 30, 1659), he was seen as a martyr. Kishan Chand Ikhlas quotes a beautiful line of verse as the chronogram of his death:

He had been Dara; he became a Major Martyr

The literary beauty of the line consists in the many connotations of the word dara all of which apply here: The name of the dead Prince; the name of the great Iranian King Dara (Darius in Greek and English); Possessor, owner; Master, ruler.

Most historians have been at pains to point out the perceived contrasts between Dara Shikoh and Aurangzeb. In fact, they had much in common, though Aurangzeb inherited more from his father than did Dara. The physical resemblance between Aurangzeb and his father was very nearly uncanny. Aurangzeb inherited his father’s ruthlessness, while Dara Shikoh was more scholarly than either his father or his sibling. But this is not to say that Aurangzeb or Shahjahan didn’t care for poetry, or learning. Indeed, I suspect that Aurangzeb was more read in poetry than Dara, just as Dara was more read in philosophical Sufism, and Vedanta, than Aurangzeb.

A number of historians have suggested that the main negativity of Dara’s character was in his haughtiness, and unwillingness to tolerate anything less than total obsequiousness.

In fact, if an anecdote narrated by the seventeenth-eighteenth century poet Muhammad Afzal Sarkhush in his tazkira Kalimatush Shu’ara (commenced 1682) is to be accepted as reliable, Dara Shikoh forgave his court jester Haji Tamkin when the latter cracked in full court an obscene joke at the expense of both Dara Shikoh and his newly married son Sulaiman Shikoh.

The main contrast between Aurangzeb and Dara Shikoh consists in their end. And unfortunately, it is the aura of victimhood and tragedy and romance around Dara’s last days and death that invests him with an almost impenetrable halo. This halo has long prevented the general public and even reasonably informed students of Mughal history from appreciating the full extent of Dara Shikoh’s learning, and his command of Vedanta and Sufism and Philosophy. Ignorance about Dara Shikoh’s intellectual attainments is so wide that most of us don’t know that he was a serious Persian poet, and not just an occasional poet like most of the major Mughal Princes before him. Very few of us know that he wrote poetry with the takhallus Qadiri and compiled a not insignificant, though slim divan of his poems.

I am aware of very few assessments of Dara Shikoh as a poet. The few that are accessible to me, including a paper by Asif Naim Siddiqi of Aligarh, don’t place much value on his poetry. Asif Naim has in fact asserted that the poetry of Dara Shikoh is not really in the mainstream of Persian poetry of his time because it’s not in the sabk-i hindi (Indian Style) which became the prevalent mode of Persin poetry from the time of Akbar.

There is no doubt that what first strikes a reader of Dara Shikoh’s poetry is its didactic and hortatory tone. It seems that true to this reputation of being a stern master, Dara Shikoh the poet is exhorting and admonishing the reader all the time. There is also an obvious stress on certain themes, small in number: themes which are superficially similar and relate to the status of man and his reltionaship with the Divine. But in fact, there is more to Dara Shikoh’s poetry than strikes a cursory reader. He is certainly not with poets like Mirza Razi Danish, or Abu Talib Kalim, the leading poets of his time, but he cannot be summed up in a routine paragraph or two by saying that he was one of the many leading Mughal princes of the blood who wrote poetry in their spare time, if spare time they ever had.

First of all, Qadiri comes through as a master of the language. In fact, the one poet whom his poetry often calls to mind is Rumi, and not because of Rum’s Sufi themes, but because of his perfect mastery over his medium. There have been many, unfortunately more among the Indians than the Iranians, who have blamed Indian Persian born poets—with the honourable exception of Khusrau—for not having sufficient command of colloquial, idiomatic Persian. This accusation, even if true, cannot be laid at the door of Dara Shikoh. If ever one wrote like a native speaker, it was Dara Shikoh. The very first ghazal, which expresses Vedantic ideas though with some influence of Shaikh Muhyi’uddin Ibn- Arabi, perhaps through the teachings of Shah Muhibullah Ilahabadi, shows great command of language and felicity of expression. I give below as literal a translation as possible:

GHAZAL 1

Everything exists in my being:

This, my external apparentness, is actually

a hidden treasure.

Although I hid my voice behind a curtain,

Yet my song became apparent through the

reed.

I saw nothing but my own self;

It wasn’t the Other who made

his appearance through me.

Imagination’s creatures are mortal, not I;

My appearance is forever existent.

My head is bent, because it is toward me

That I prostrate myself.

I captured myself, and I came to rest,

seated:

How happy, how fortunate, is my posture!

There is no difference: Qadir (The All

Powerful) or Qadiri (Qadir’s follower)—

All my contingentness is nothing but

Necessity.

It is clear that the mastery here is in the apparent simplicity. It would need a Shah Muhibullah Ilahabadi to do justice to the depths of thought in this ghazal. In Persian, it would need a Khusrau to attain this level of compression, except, of course that Khusrau was never triumphalistic as Qadiri is.

Qadiri repeats in other ghazals many of the themes of his first ghazal, and his didactic tone can sometimes become somewhat jarring. But that is just an illusion. Qadiri’s poems can also express the various and variegated moods of qabz: It is the mood which prevails upon the traveller on the Path when finds his progress thwarted: his ability to absorb the Divine Radiance seems to have shrunk.

There are numerous states of feeling or mood that can inicate to the reader what qabz can do to the seeker. According to the Chishti Sufis, it could also presage confiscation of past levels of attainment and cessation of future favours.

Let’s look at a ghazal that typically reflects the moods of loneliness and the state of unreaching:

GHAZAL 187

Please become the life for my withered soul!

Remove my body’s pain, be my physic.

I fall from my feet in your Path—

Make me your prisoner, and walk away.

Enemies give me pain, and misery;

By my guard against these dogs, these monsters.

I lost all my luggage, all that I had:

Become my goods and luggage, become my

Quartermaster.

My body is your home, your hermitage:

Enter in happiness, and illuminate.

Regard me as nothing, and do kindnesses,

Be the cause for Benevolence, Grace and

Selfless good.

Your friendship, your discourse, are for

Qadiri alone—

Enter his abode, and be the Master.

The tone here is nearer to the early Sufi poets, like Iraqi and Sanai; in fact, there is more passion here than one would find in Sanai. But Qadiri’s talent shows itself best in his ruba’is. Traditionally, the ruba’i has been used for Sufistic themes of the intellectual type, that is, the theme and thought is mostly Neoplatonical, with resonances of Ibn-e Arabi. Most Sufistic ruba’is can be read as a love poems even, because they have more intensity of feeling, than of thought.

Qadiri wrote more than a hundred ruba’is—a remarkable number seeing as how his ghazals, mostly short, are just 216. He prefers Vedantic-Sufistic themes, as in his ghazals, but he very often adopts the complexity and wordplay which are the distinguishing characteristics of the sabk-i hindi poets. The other technique that the sabk-i hindi poets perfected if they didn’t invent it is called tamsil: The poet makes a statement (da’wa) then brings in an exemplum to ‘prove’ that statement. Dara Shikoh shows himself quite adept at this in his ruba’is. This is ruba’i number 82:

If you wish to be counted among those

those who have the power of sight,

Move on from mere words to the inner

experience

You don’t become a believer in Unity by just

saying the word:

The word ‘sugar’ however repeated, doesn’t

sweeten the mouth.

We can see the neat ‘argument’ that proves the da’wa. It is also a proposition in linguistics, for the word and the thing it stands for are not the same. Ruba’i number 59:

He who has gnosis brightens and ornaments

your heart, your soul,

He makes a garden out of the thorn that he

pulls out from its place;

He who has attained Perfection liberates

everyone from error:

One candle lights up a thousand more.

I will now present one last ruba’i, which shows a perfect fusion of Vedantic-Sufism with the sabk-i hindi mode of poetry. Ruba’i number 100:

Nothing is but Truth; why do you imagine

this to be hard to follow?

I say: you are nought but Truth, and I don’t

lie;

If there are a hundred waves on the ocean’s

surface

There’s not one that can create a rupture

in the ocean’s unity.

It is true that Qadiri’ poetry doesn’t have some of the themes which are among the special features of sabk-i hindi poetry: unreachng; absence in resence; failure of communication, even rejection of communication; intensive use of metaphor, where a metaphor is in its turn treated as fact. All this could not coexist with Qadiri’s special kind of Vedantic Sufism, and his vision of the reality of the divine-human of existence. But his language is certainly closer to the sabk-i hindi poets than to anyone else.

Qadiri’s poetry has a flow, a smoothness of rhythm, called ravani by Khusrau who placed the greatest value on this quality of poetry. Of course, Qadiri never tested or stretched himself: he wrote no qasida (not even in praise of the Prophet, or to celebrate the Power and Existence of God); he wrote no masnavi either. So it can be said that poetry was, after all, a marginal activity for him. This must not, however, deceive us into believing that he wasn’t a substantial poet.

******

Author’s note: 1. All translations have been made by me. 2.The text that I have used is Iksir-e Azam, Diwan-e Dara Shikoh, ed. Amad Nabi Khan, Lahore, University of the Punjab, 1969. I am grateful to Professor Asif Naim of Aligarh Muslim University for making available its copy to me. 3.The pronunciation shikoh instead of shukoh, and in fact, of many other Persian names and words might jar on the ears of the native speakers of Persian.. I find it perfectly natural, and certainly more comfortable, to stick to my Indian pronunciation. Still, I apologize to those of my readers who would have liked me to follow the Iranian mode. 4.Presidential Address, Conference on Dara Shikoh, Context of History, Context of the Present Anjuman Taraqqi-e Urdu (Hind) New Delhi, March 22, 2013.

Shamsur Rahman Faruqi Urdu poet literary critic, novelist, in short a polymath whose contribution to Urdu literature and to Indian letters has been immeasurable. His historical novel Mirror of Beauty, self-translated from Urdu original sheds light on a historical period much abused by conventional (colonial) historiography.

Shamsur Rahman Faruqi in The Beacon

Mir in Chandigarh

Urdu Writing Over Two Centuries On Nation, History, Culture

CONVERSATION WITHOUT MAPS

Leave a Reply