A foreword

In 1905, Lord Curzon announced his decision to bifurcate the Bengal province, into Hindu-majority West and Muslim-dominated East. The proposal met with widespread outrage. Once the formal division was announced — rescinded in 1911 and re-imposed in 1947 — the call to boycott bideshi (foreign-made) products in favour of swadeshi or Indian goods took root. As anti-colonial sentiments ran high and idealists carried out a series of attacks against the British, tensions between Hindus and Muslims escalated into violence.

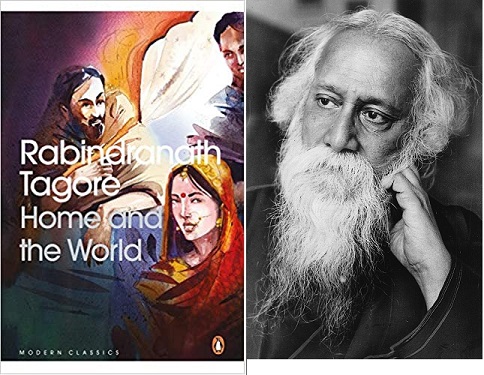

This political scenario forms more than just the background of Rabindranath Tagore’s best-known novels, Gharey Bairey (The Home and the World), published in 1916; it drives the narrative and molds the characters. More than a hundred years later the novel needs to be read for those antinomies that would germinate and haunt this land in a way reminiscent of William Faulkner’s notion that the past isn’t dead, it isn’t even the past: Hindu majoritarianism against pluralism, tradition and modernity, evolution versus violent revolutionary change, home and the world, man and woman.

In his reading of Gharey Bairey, Pankaj Dutt elliptically contemporizes it. The Beacon opens the doors for comments and commentaries on this reading or on the novel itself as a conversation on a past that’s alive and kicking—The Beacon

Pankaj Dutt

T

agore’s novel Gharey, Bairey presents itself as a commentary on women and social emancipation, centred on a woman belonging to a landed, royal family, living in pre-independence India. She is the Rani of a minor ‘kingdom’ somewhere in undivided Bengal, a few hours from Calcutta. The backdrop to the novel is the swadeshi movement which enters the fiefdom with gusto, disrupting its otherwise peaceful existence.

The novel is a narrative of ‘stories’ in the first person, musings and reflections of three individuals – Bimala the Rani; Nikhil the overlord or Rajah who is Bimala’s husband; and swadeshi leader Sandip who introduces the idea of freedom in that region. The story is constructed upon three distinct responses that the characters individually express in the process of their interactions, within their differing understanding and personal interpretations of the swadeshi movement. Through their respective eyes they reflect and opine, not only on matters relating to traditional boundaries limiting a woman’s life and social expression – needless boundaries relating to women belonging to royal, land based backgrounds only – but also on aspects defining the swadeshi movement.

In as much that Bimala, almost to the point of destruction, is actively encouraged by both, Sandip and Nikhil, in ways so totally opposite to each other, to break the shackles of bondage thereby representing women’s emancipation, the novel prompts the reader to try and evaluate the author’s framework for understanding the larger context of social change given the specific era. Tagore wants women to cross the Laxman rekha demarcating the home and the world outside. In a literary sense ‘Hail to the Mother’ – Bande Mataram is leveraged by the author to depict and denote more than the obvious political call to action of an emerging independent nation; The catch phrase is also used to explore dimensions around the issues of women and their freedom, blended within the folds of Bengal’s traditional orientation and take, on the concept of ma Shakti – the quintessential representation of womanhood. Tagore’s comments on that society’s afflictions and internal conflicts within a storyline carrying three perspectives, makes the reader curious about the manner in which he will resolve the issues raised in the novel.

Bimala, Nikhil, Sandip : Characters in their stories

Nikhil and Sandip are old college friends from the educational environs of Calcutta who have stayed in touch. In the past Sandip has taken funds from Nikhil for the swadeshi cause. Nikhil has obliged as a friend not for political reasons. Bimala aware of this has a disapproving take on Sandip’s underlying intent and has expressed it so to her husband. She has never met Sandip before. The story begins with Sandip coming to Nikhil’s territory bringing swadeshi. Nikhil offers him the comfort of his home, aware that the swadeshi movement would follow. Sandip enters he calm and lovingly lived lives of Bimala and Nikhil in their fiefdom. And creates a storm.

Being the friend, the host and the Rajah, Nikhil indulges his friend and tolerates his political beliefs despite their basic and ever increasing differences on the swadeshi movement’s practical motive and objectives. At another level, his stated belief to his wife Bimala, that a woman has the right to individual freedom to express herself beyond the home and the hearth, allows her to open her mind’s door when the opportunity arises. Sandip’s instant charismatic effect on her makes her want to interact with him.In the process she begins to explore her personal freedom and the understanding of swadeshi politics, with him.

Nikhil doesn’t dissuade her from entertaining Sandip in the inner sanctum of their home for apparent confabulations on the movement as she increasingly becomes a part of swadeshi or stepping out of the bounds of the zenana; all which are otherwise taboo for the bahuranis of such households. The freedom that he ‘grants’ gives rise to consequences, unforeseen by him.

At yet another level, Nikhil, the overlord, sees the onslaught unleashed on the local market and its trade preferences by the swadeshi movement and its call for the boycott of foreign goods. The equilibrium, on all fronts is disturbed.

As the story unfolds, his predicament gathers pace. While believing in the rights of individuals to hold their own view and practice it Nikhil freely, faces the harsh realities of the outcome of such freedom, including the Machiavellian political moves that challenge the noble intent of the concept of rights, as he understands it. His belief in the practice of such values, ironically, ensnares him in a tangle, and as the story progresses, he struggles in despair to find a handle on why in reality the results are contrary and compromised. That the anachronistic society he resides in, and to which he actually conforms in practice, does not echo his idealistic and simplistic understanding of the tenets of individual freedom in the wake of the aggressively growing swadeshi, challenges him intellectually, personally and politically. The emerging conflicts that disrupt his family, the society, the economy and the colonial political rule he locally enforces, pose a serious dilemma for him. As matters precipitate and complexities unfold, his approach to handling issues both Gharry and Bailey, posits interesting questions in the mind of the reader about Tagore’s perspective on the society he portrays and the path to the resolution of conflicts therein.

Bimala is awe struck by the charisma Sandip exudes. Sandip, aware of the effect he has on Bimala begins to leverage his advantage for personal and political gains and engages Bimala with unwavering intent. In an initial interaction between the three of them, Sandip openly mentions her as his logic for staying on and making their place the centre of all his activities

….Then let me speak out my mind…I have never yet found any one source of inspiration suffice me for good. That is why I have been constantly moving about, rousing enthusiasm in the people, from which in turn I draw my own store of energy. To-day you have given me the message of my country. Such fire I have never beheld in any man. I shall be able to spread the fire of enthusiasm in my country by borrowing it from you. No, do not be ashamed. You are far above all modesty and difference. You are the Queen Bee of our hive, and we the workers shall rally around you. You shall be our centre, our inspiration.” (47)

With his magnetic personality he poetically translates the politics of swadeshi onto her being and builds a pedestal for her … he elevates her to the status of the divine ma Shakti with all godly capabilities. He symbolically links this image of her to the emerging nation’s motherhood and its call of Bande Mataram. Hail Mother becomes a multi-layered catch phrase wielded by Sandip that works well for his political ends; and for entrapping Bimala. She, in a way, perceives the dangers of such a liaison rapidly invading her personal space, despite the ten years she has spent in deep devotion and dedication to her husband. But she is confused. While weakly aware of the deviousness of his politics and charm, and her own failings, she does not fully comprehend the implications; she gets carried away and glosses over the pitfalls because this new experience for her is unique, heady, liberating and indulgent.

Sandip spares no guile to achieve personal and political mileage and benefits; exercising command over Bimala by building in her the belief that she is ma Shakti providing divine inspiration for the movement, he hopes to acquire an oblique control over Nikhil as well. He works insidiously to build a personal space of endearment with her, consciously undermining her relationship with Nikhil and thus gaining her complete allegiance. In Sandip’s words ….

“The upshot was, that after this Bee (in the story Sandip openly gives her the name and status of Queen Bee) began to send for me to the sitting-room, for a chat, without any contrivance, or pretence of its being an accident. Thus from bare suggestion we came to broad hint: the implied came to be expressed. The daughter-in-law of a princely house lives in a starry region…..what a triumphal progress of Truth was this which, gradually but persistently, thrust aside veil after veil of obscuring custom, till at length nature herself was laid bare. Truth? Of course it was the Truth! The attraction of man and woman for each other is fundamental….I am enjoying the sight of this truth, as it gradually reveals itself….and sweet are the deceptions that deceive not only others, but also Bee herself.”(60-61)

It is just a matter of time before he demands money from her for his political conspiracies. All this, and more, he couches within the call of Bande Mataram which leaves Bimala overwhelmed.

Contributing characters in the story

The cautioning voice in the story is that of Bara Rani, the widow of Nikhil’s elder brother; the sister-in law. From her perch of widowhood confined within the zenana, she sees the path Bimala is embarking upon…dangerous and self-consuming. Her cautions are unheeded by Bimala who is beside herself in her acquired pivotal role in swadeshi, enjoying her new found freedom. Bara Rani’s heavy hints at caution fail to evoke a positive response, as Bimala anyway considers her sister-in-law an irritating, intrusive, insincere and jealousy-ridden widowed relative whom she can’t wish away; one who manoeuvres her husband using their childhood association to obtain benefits. Bimala’s new found path to self-discovery guided by a charismatic leader who pays flattering obeisance to her and her womanhood, coupled with the band of swadeshi followers who join in furthering her glory, are a heady mix rendering Bara Rani’s concern for Bimala a hopelessly lost cause. In Bimala’s words… “When he called me the Queen Bee of the hive I was acclaimed with a chorus of praise by all our patriot workers. After that, the loud jests of my sister-in-law could not touch me any longer. My relations with the world underwent a change. Sandip babu made it clear how all the country was in need of me….”(55)

Bimala’s foundations of marriage are shaken leading to a serious strain with her husband as she begins to see herself in a new found role – that of a powerful woman; as the energy inspiring a movement forward with the slogan of Bande Mataram; as ma Shakti a force necessary for swadeshi to succeed. Nikhil sees this play unfolding, but prefers to stay within the strength of his beliefs…he lets her take her course even though he is aware of the destructive power she wields.

“I longed to find Bimala blossoming fully in all her truth and power. But the thing I forgot to calculate was that one must give up all claims based on convention rights, if one would find a person freely revealed in truth….Bimala had failed to understand me in one thing. She could not fully realise that I held as weakness all imposition of force. Only the weak dare not be just…. I had hoped that when Bimala found herself free in the outer world she would be rescued from her infatuation for tyranny…Her love is for the boisterous….I know Bimala finds it difficult to respect me for this, taking my scruples for feebleness, – and she is quite angry with me because I am not running amuck crying Bande Mataram.….(43,44)

Nikhil’s character presents a mix of conflicting dimensions and duality. On the one hand he is this young, educated and modern thinking person who believes in the virtues of the superior western value system – he is a graduate from Calcutta who goes on to obtain a Master’s degree as well – that allows him to build on thoughts and beliefs that are apparently liberal with a sophistication in articulation and a sense of cultural freedom and advancement. He is a teetotaller and abstains from the other two associated decadent practices as well, that of women and song. Bimala is deeply grateful for and respectful of this dimension of his personality because for a Rajah this is uncharacteristic. For Nikhil, his elder brother’s untimely demise because of these very indulgences makes him abhor them.

Nikhil believes women have the right to freedom of expression and to break from tradition and social norms. He espouses, although at a private level, the cause of women’s emancipation to his wife and coaxes her to follow the path to expression and freedom. This, in fact, Bimala finds difficult to understand and resists it as she neither has any precedence in her life, nor is she privy to any other experience elsewhere that would encourage her to break from tradition and the accepted social and cultural practices of a Rani.

Till she meets Sandip and becomes a part of swadeshi.

Beyond the home, and into the world outside, Nikhil believes that every individual has the right to decide what is correct for him. For example, a trader in the market place must do what is right in order to survive successfully; that if a person prefers to sell foreign goods, no one has the right to force him to sell sub-standard indigenous goods that lack demand and accrue losses. Force is abhorrent to his free market spirit and therefore burning foreign goods by swadeshi which are privately owned, is definitely wrong, and a violation of individual freedom and rights.

Contrary to all of the above, Nikhil’s actual life is a canvas of landed gentry practice, a feudal lord, a Rajah controlling the market as its patron and collecting tax from peasants and traders, holding sway over their lives …. Down to his home where he doesn’t question the purdah system, accepts and observes visitation norms to zenana, et al. As the overlord, he lives his traditional life, both inside the home and in the world outside. He fits the British Raj’s bill perfectly as the ideal representative of the system conducive to imperial rule. Nikhil’s statements and belief in the tenets of progressive virtuosity is, in practice, quite the opposite. This dichotomy is evident to the reader.

The novel includes other characters as well that contribute towards the main theme. Panchu’s tale of a marginal farmer who loses his land and becomes bonded to a neighbouring zamindar is a portrayal by the author of Nikhil’s fairness of his belief system, intents and actions. Nikhil’s teacher, Chandranath babu, another character in the novel, reinforces Nikhil’s viewpoint through the story line, marking a caution against the violation of principles governing individual freedom; at different points in the novel Chandranath babu questions in various ways the logic of swadeshi’s objectives and the means being deployed to achieve it. The novel, through these complementary sub-stories, attempts to raise some dimensions of ideological differences between the swadeshi concept of change vis a vis Nikhil and his teacher’s beliefs in supporting marketplace logic and individual freedoms.

The story, simply outlined

Bimala enthralled by Sandip’s political and personal charisma becomes swadeshi’s heroine, primarily in her own eyes. Nikhil is the impediment, the obstructive element within the grandness of the unfolding movement – he is embarrassing for her, Sandip and swadeshi. The dialogues and debates between Sandip and Nikhil, mostly in her presence, see her siding with Sandip, for, the glory of the nation’s freedom is supreme. Nikhil however considers such expression for the country as blind and akin to worshipping god; for him the issue of individual rights is more important. Swadeshi uses force, the imposition of which means weakness to him….

“only the weak dare not be just….they shirk their responsibility of fairness and try quickly to get at results through the shortcut of injustice.”

Youth, unemployed and suggested in Bimala’s narrative as lumpen, are encouraged to join swadeshi and come to the fore …. Burning of foreign goods is a form of struggle adopted by swadeshi which is a serious bone of contention between the Rajah and Sandip. While living in the same house and engaging in debates, Sandip fails to convince Nikhil about his point of view on swadeshi and so is unable to garner Nikhil’s support. Nikhil continues to wield control over the market and the traders, which Sandip is unable to break. The movement thus suffers and the required momentum for it to gain ground is a challenge….Sandip needs to do something fast about it.

Meanwhile the growing communal tension emerges given the fact that traders in the market are primarily Muslim and the trigger of cow slaughter becomes a matter for the Rajah to opine on, while having to ensure the functioning of the market in the context of swadeshi’s ban of foreign goods.

Sandip in an attempt to precipitate events in favour of his movement makes a plan to garner the support of the very person, a Muslim, whose boat he had clandestinely arranged to be sunk as part of his earlier tactics to disrupt the water way route for the entry of foreign goods. The new plan needs money to help the person buy a new boat in order to get his undying allegiance to Sandip and his cause, which would help gain entry into the market dynamics. So who else but Bimala to tap for funding him in his hour of need? Time is now ripe for him to redeem all investments he has made in her!

And so Bimala is approached surreptitiously by Sandip for a sum of money which is far more inflated than what is actually needed. He doesn’t share this fact with her. He simply asks for the full amount. Bimala finds it very high but cannot express her inability to raise it, as she is completely under Sandip’s influence. Full of herself, she believes that her womanly hold over her husband will prevail upon him to cough up the funds. This does not work to the disbelief of Bimala. Nikhil had never in the past included her in his financial dealings, being the Rajah’s prerogative and domain and feels it inappropriate to indulge her now. Shocked, her ego hurt, unwilling to decline Sandip, Bimala embarks upon stealing money kept in a locker of her own home, operated by her husband.

The extent to which she owes her soul to Sandip’s store surprises even her and she begins to realise the folly of Sandip in her life. But she arrogantly asserts that she would get the money and proceeds with the theft, handing it over to Sandip. Unfortunately the money, in gold, Nikhil was proposing to transfer to Calcutta in favour of his sister-in-law. This fact complicates matters for Bimala. She hatches another plan now to replace the amount by pawning her jewels which task she gives to her deeply devoted adopted brother Amulya who is also a devout follower of Sandip and one of swadeshi’s foot soldiers.

Amulya not wanting to pawn his sister’s jewellery decides on his own to attack the government sub treasury and steal the exact amount required to be replaced. But while doing so he injures the guard which adds to the official furore and sets off sustained investigations in the area. The police are out on hunt now everywhere….looking for the perpetrator of the theft at Nikhil’s home and the attack on the treasury.

Whatever the intrigue of these events in the story, a third dimension, that of communal forces, suddenly rears its head in the region, the social base being the Muslims in the local market. Agitators and activists from other parts of Bengal have infiltrated the region gathering forces to fissure Hindu-Muslim fraternity. Matters of swadeshi politics and independence from British rule, on one side, the continuing issue of sale of foreign goods by local traders, on the other, are now joined by a build-up of communal forces. Seeing the situation get complicated, tense and getting out of control, Nikhil decides that Sandip should shift out to Calcutta, and his entire family as well. On Sandip objecting to being so directed, Nikhil leaves him with no option….for the first time Nikhil asserts to Sandip that he would consider shifting him forcibly if required, and against his wishes!

In the last interaction between the three of them, Sandip is agitated at the turn of events and speaks out in anguish and hurt at Bimala, Nikhil and the situation alike; he does so at his poetic best …. Waxing eloquent on her he speaks, charged with emotion, about the inspiration she provided him and the movement. Bimala who had by now begun disliking him reacts to this part of him, again with awe and reverence. She acknowledges within herself that Sandip has this power to invoke in her love and hate for him, simultaneously. Sandip finally speaks out and acknowledges the failed scheme he had hatched and hands back the ornaments to Bimala and leaves.

Sandip leaves just before the political situation explodes but Nikhil and Amulya are caught in the cross fire while attempting to douse the communal fire. In the style of a novel, the story ends with the returning party informing of Amulya having been shot dead and Nikhil with a serious head wound, leaving it to the reader to decide his fate.

*

Gharey, Bairey was written against the backdrop of a tumultuous moment in Indian history that threw up issues that still haunt us such as Swadeshi, communalism and women’s empowerment.

The movement’s leader Sandip is portrayed as a political schemer and lacking in personal integrity–morally corrupt. In none of the reflections and musings of the three characters is it suggested otherwise. In fact Sandip’s own musings are the most revealing about his intentions. Does Tagore sketch such a persona simply as a need of the story or is actually commenting on swadeshi’s character? The novel leaves it to the reader to decide as no hint of an alternative interpretation, insight or practice about the movement is given in the novel.

Swadeshi, seen from market place dynamics, is one of indigenously produced goods coming in direct conflict with and in opposition to established, imperial/foreign goods. The economics and politics of swadeshi’s reasoning for positing it thus, however are not explored or explained in the novel. Prima facie the novel wouldn’t need such reasoning if it didn’t engage with any debatable point.

In the novel however, the absence of swadeshi’s economic and political foundations has a significant bearing on a contentious point made in the story – one of subversion of individual freedom and rights (i.e. when swadeshi in its political expression burns or destroys a trader’s foreign goods, which are his private property and which provide him his livelihood ) in the context of the inability of indigenously produced goods (stated as sub-standard and rejected at the market place) providing traders an alternative source of viable livelihood. In this argument a trader is apolitical and agnostic to goods being traded by him. The goods he trades must sell profitably, thus assuring him his individual freedom and right to life. For him the demand and sale of foreign goods as it stands are established and indisputable.

Conceptually, rights of one set or category of human beings can be discussed only in the context of complementing or contravening rights of another set of human beings. In this case it should have been the producers of indigenous goods who, politically, economically and ideologically, could have posed a challenge to traders supporting the sale of foreign goods under the powers of a feudal king owing allegiance to the crown. But the novel does not contextualise producers of indigenous goods in the story. It prefers to view indigenous goods as challenging traders’ rights. The fact that manufacturers of indigenous goods are local people who are suffering, trying to eke out a living, while being out-competed by foreign goods is not considered in the story.

Does Nikhil’s support of the local market economy over which he ruled, and also extracted taxes from, for his imperial rulers, present a political standpoint suggesting that status quo be maintained? Is Nikhil, therefore proposing that market equilibrium for imperial rule and its goods be left un-disturbed? Does Nikhil, arguing from his point of view against swadeshi, represent an inter-dependence and nexus between traditional feudal forces and imperial rule and its practical reflection in the economy? Or is it that swadeshi in the way it is presented in the story, could also be construed an incapable force, one that cannot provide leadership for an independent and indigenous path of development?

Communalism gaining presence in that region, aided by the fact that Muslims dominate the local market, emerges as a political force rather suddenly in the late portions of the novel. While swadeshi, Sandip’s machinations, Nikhil’s dilemma and Bimala’s confusions take centre stage in most of the story, the growth of communal forces is not presented overtly or clearly in the novel’s progression. The issue of cow slaughter is all too casually touched upon as a matter of sensitivities between the two communities, on which the Rajah needs to opine and guide the Hindu community. In fact what could as well be construed by a reader is that the emergence of communal forces was due to swadeshi!

Swadeshi that disrupted market equilibrium; swadeshi that was led by an opportunist and unscrupulous leader who had a band of unclear followers; swadeshi that couldn’t provide a genuine alternative for the trading classes to succeed with. And thus the growth of communalism.

Was communalism an active outcome of swadeshi’s misadventure and disruption of the market place? Does the novel suggest that had not swadeshi come to that region and had market place equilibrium been maintained with the British Raj getting its share of the loot from its tax collector rajahs and zamindaris, the sublime life of Nikhil and Bimala representing that society, would have continued blissfully? Or was communalism a new ploy initiated by the British Raj to remove the threat of competing indigenous technologies and formation of independent market forces, while undermining the unity of a national liberation process?

The novel is seen to comment on the restrictive boundaries that govern lives of women in a patriarchal society, by way of a story that explores opportunities for independence and self-expression of its protagonist, Bimala. That her husband, a well-educated feudal lord, possesses a western outlook and believes that as a woman, his wife has rights to individual freedom, augurs well for the reader awaiting the story of change to unfold in an interesting backdrop of swadeshi. With such a rich offering, the reader anticipates a remarkable discussion on the issue of women’s emancipation. However the reader is faced with conditions in the story line that limit exploration of a topic that has wide and significant social implications.

The novel explores women’s emancipation issues through the eyes of one woman only; and this woman belongs to the most elite section of rural society. As a set of first person narratives, none of the spokespersons – Bimala, Nikhil or Sandip, prefer a wider canvas of discussion viz women as a gender in society, women belonging to different strata of Indian society, women and patriarchy, women as workforce etc. Further, Nikhil’s approach on the subject is one of a personal grant and is seen only in the context of his wife and her individual rights. Matters within the core of women’s freedom and expression such as observance of purdah, zenana etc. which operate in his very household, are not even acknowledged, forget commented upon or discussed within the context of the issue.

The purpose of swadeshi as a political reflection of an emerging nation’s aspiration seeking independence from colonial rule, and as a personal intervention in the life of Bimala, is qualified by the story. Qualified to the reader through the coloured eyes of a suspect political leader who skillfully plays upon the intellect and emotions of a naïve woman. Simultaneously the husband is portrayed as one with an intellectually superior and purist attitude. He believes in truth prevailing on its strength and does not wish to intervene in guiding matters in the hours of confusion, but laments within himself the steady erosion of long-standing bonds in their marital relationship. Bimala is presented as a vulnerable person, confused but with an ego, finally ending as a failure in a man’s wily world; a world that she cannot navigate.

Such portrayal influences the reader’s judgement raising the question of whether women can really be given the freedom to engage with the opportunity of gaining independence. Do they have the strength of character and capability to emerge successfully from the yoke of a traditional society at all? And perhaps much worse for women belonging to various categories of weaker and oppressed sections?

Most significantly, and pathetically for Bimala, the story is one of the crushing of a woman’s spirit and endeavours, and finally of abandonment – of her ideals, of her struggles, of her intellect, of her belief in herself, of her status, of her very being. She is reduced to nought. From her glorified status of being an inspiration, she is reduced to a helpless caricature of her original self, having to follow a simple order to shift to Calcutta. No alternative perspective, no choice in life is afforded her.

She is a woman who has to submit to being a helpless bystander, in the last sequence of the novel, hearing of Amulya’s death and her husband’s grievous injuries. She is stripped of all her social moorings. What an ignominy for one who was made to believe in the symbolic prowess of ma Shakti residing in her; on one who was meant to inspire an entire epochal movement! For her there is no resolution except confusion both personally and intellectually. Her downfall is cruel and indeed tragic.

*****

Notes

The quotes are from:

Rabindranath Tagore’s “ Gharey, Bairey - The Home and the World” Published in English by Wisdom Tree, reprinted 2012.

Pankaj Dutt schooled at St.Xavier’s, Calcutta. read Economics at Fergusson College Poona. He insists that the old world spelling is by choice. He has been variously, tea-taster and blender, in corporate management, advertising, an exporter of fashion leather goods and writes on the dynamics of social change. He enjoys Spoonerism – always begins by calling himself Dankaj Putt, and then indulges himself; Golf. Golf. And more Golf !! Adventure mostly motoring-based, with a go-anywhere attitude; Car rallying – claims to be the oldest extreme category license holder in the roster of The Federation of Motor Sports Clubs of India. He harbours the delusion of one day becoming a consummate Djembefola. (Hah, the Niger river convulses in spate at the very thought!!)

I have enjoyed reading Pankaj’s piece on Home and the World. He has delineated many of its issues, ambiguities and silences in great detail and in the finest language possible. My hat’s off for that! However, there are anachronisms in some of the expectations he is making of the text. I also have a problem with his reading of Bimala’s predicament. She isn’t a failure! The process of stepping out of the home into the world has its own highs, lows, misgivings and learning….. I would like to believe that Tagore has done a competent job of getting under the skin of a woman character by having her write her own story…