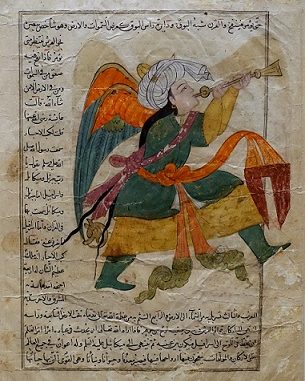

Courtesy: Freer Gallery of Art

Genealogies of Silence in Israfil’s Death

Riyaz Latif

The archangel, Israfil (customarily identified with the Judeo-Christian Raphael), is dead: we are at the cosmic burial of all sounds, and the ensuing silence has a circumference so endless that it presages an all-encompassing erasure. We stand on the hushed ruins of eschatology, at the definitive instant of Time’s cessation which was decreed to be inaugurated with sound, when all would be wakened to creation once again. It is sound that animates the vibrant whirring in all, in everything. But now, mortality has consumed the very sound-bearer who would announce the Resurrection; in Israfil’s death, Noon Meem Rashid, through the majesty of his elegy, brings us face to face with the soul- shattering episode of the death of sounds. Israfil, the metaphoric quintessence of all sounds, is at repose, dead: Israfil, that resplendent archangel with his clarion-horn, the one who shall blow the trumpet to raise the dead on the day of Judgement, the illimitable undying spirit of sounds. No one to shape and craft sounds anymore to their consummate apotheosis; no one to animate space and time through a sonic release. Instead, all sound – in its literal, emblematic, metaphysical significations – is interred into the crypt of silence so overpowering in magnitude that the order of the worlds known and unknown seethes with an elegiac hush. In that elegiac hush, each entity, animate and inanimate, stands at the antipodes of itself.

At the outset, Rashid makes us a participant in his lyrical elucidation by issuing an elegiac imperative: weep tears on the death of the bearer of all sounds; weep tears for the silence that encroaches upon each fiber of our being. Through our tears thus, we are enjoined to mark this resounding occasion, lament the death of sounds’ celestial embodiment, and as an effect of this muting of the now and the hereafter, mournfully bear witness to each thing’s relegation – words, thoughts, materiality, identity, liberty, even space and time – into nothingness.

And what are the properties of the unchained ripples generated by the passing away of this indomitable spirit of sounds on whom legions upon legions of angels inundate all realms with their lamentation? In this silence, we are faced with the death of all articulation, all expression. For, as Rashid reveals to us, the death of sounds disseminates an erasure which enacts a fatal mimesis in all things vibrant and static, material and intangible – in Israfil’s death, silence is embalmed on everything ranging from domes, vaults, walls and pulpits to the preacher’s sermons, discerning ears, and sagacious hearts. It heralds the demise of our capacity for cogent cerebral contemplation, our last existential refuge, according to Rashid.

From a more routine philosophical position, colossal silence might even be worthy of an opportune embrace. But when one is unwittingly extricated from one’s silence into a greater imposed one, when that extrication is delineated by a dissolution of one’s meaning and identity (when in a clamorous solitude, one cannot even recall one’s own name), then the whole prospect begins to acquire the contours of an elegiac disquiet. Here, we could readily invoke Antonio Porchia’s gnomic remark: “In my silence only my voice is missing.”1 And the absence of our voice is the interminable apocalypse that Israfil’s death wrecks upon us. In that sense, Rashid’s poem is an elegiac chant for our contemporary human condition; it is a sad incantation for the world of crass noise on the one hand, and dense solitude as well as severe loneliness on the other. Nearly imperceptible but at the core of the elegy is the “universal man” who has lost the meaning of his existence in the churning defeat of human values. In an inimitable irony, this loss of meaning, this collapse of communication and expression which turns into a curious nightmare in Israfil’ death, bespeaks a silence so composite that even the oppressors of the world can only dolefully dream about strangulating the voices of the dispossessed. There is no voice, there is nothing to suppress! These then are the politics of silence; in Israfil’s death, in the burial of the indomitable spirit of sounds, the vectors of empowerment – at a political, social, existential and even metaphysical level– are subversively reversed.

In Israfil’s death, thus, Rashid elegiacally unfolds for us several genealogies of silence: the deathly hush of our experiential and emotional life lost in the unidimensional colorlessness of our times, of our identity in faceless crowds, of our spiritual restiveness in the prosaic motions of days and nights – helpless human condition and an unrelenting forbidding universe. The inventory of silence, signified by the death of the allegorical exemplar of sounds, Israfil, is extensive, and Noon Meem Rashid’s stately lyrical explorations in Israfil’s Death merit contemplations in a much more expansive, layered manner than what is attempted here in these stray prefatory musings on the poem. Further contemplations are incumbent upon us in order to willfully possess the ‘silence’ of our condition, and if we tamper with Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s phrase a bit, we would admit that the silence of long-forgotten things hangs heavy on our eyelids.2 But for now, let this brief note be an ars poetica for Israfil’s Death and Noon Meem Rashid’s poetic world.

***

Israfil’s Death

Noon Meem Rashid.

(Translated from Urdu by Riyaz Latif)

weep tears on Israfil’s death

that confidant of Gods, that bearer of Discourse

infinite spirit of human sound

illimitable voice of the firmament

hushed now like a fragmentary alphabet

weep tears on Israfil’s death!

come, let’s weep tears on Israfil’s untimely slumber

at repose he is, near his clarion-horn

as if a tempest had gushed him on to the shore

on the sands of the shore, in the shimmering light, quiet

he lays somnolent under the wing of his clarion-horn!

his turban, his tresses, his beard,

how dust-defiled!

beneath whom once stood being and non-being!

how, his clarion-horn, far from his lips,

lost in its own cries, its own laments,

due to it used to dazzle the sluggish and the swift!

weep tears on Israfil’s death –

he was a tumult embodied, a chant incarnate,

he, an insignia of ethereal voices stretched from origin to eternity!

in Israfil’s death,

ring within celestial ring, angels elegiac;

Adam’s progeny, tresses in dust, wretched

Eyes of the Almighty, dark with grief

the ambient hum of the heavens, soundless

no clarion-call emerges from the nonmanifest realms

in Israfil’s death

wherewithal of sounds shut on this world;

the subsistence for minstrels, the sustenance for lutes;

how shall the chanteuse sing now, and what?

the heart-strings of listeners, quiet!

how shall the dancer swirl now, and undulate?

the grounds and the portals and the walls of soirees, quiet!

what shall the town-preacher sermonize now?

the thresholds and the domes and the minarets of mosques, quiet!

thought’s fowler, how shall he spread his snare?

the birds of dwellings and mountains, quiet!

in Israfil’s death,

death of the listening ear, of speaking lips,

death of the visionary eye, of the sagacious heart

due to his breath rose the flurry of dervishes,

conversations of the spirited with the spirited —

the spirited—who today are solitary and withdrawn

ecstasies of tanana hu gone now, and yaarab ha too, vanished

now too vanished, every clamor of streets and lanes

this, our last refuge too, vanished!

in Israfil’s death,

this world’s time as if had stopped, ossified

as though someone had devoured all sounds.

such loneliness that no recollection of perfect beauty

such howling silence that no remembrance of one’s own name

in Israfil’s death

the Lords of the world too

shall long for dreams of muting the tongues;

in which there would be whispers of the dispossessed

the dreams of such lordship

Translator’s Notes 1 Antonio Porchia, Voices (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1988), p. 20. 2 Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s original is: “The weariness of long-forgotten peoples hangs heavy on my eyelids.”

N.M. Rashid or Noon Meem Rashid was he was popularly called was born on August 01 1910 in undivided Punjab. John Keats, Robert Browning and Matthew Arnold were early influences but Rashid soon developed his own world view his poetry traversing the struggle against domination and the relationship between words and meanings, between language and awareness. He rebelled against the traditional form of the 'ghazal' and became the pioneering exponent of free verse in Urdu Literature with his first book, 'Mavra'. He died in London on October 09 1975. Along with Faiz Ahmed Faiz and Miraji he is considered one of the founders of modern Urdu poetry.

Riyaz Latif holds a doctoral degree in art history with a primary concentration on premodern Maghrib (North Africa), and the Mediterranean basin. After a postdoctoral fellowship with the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture at the MIT, he taught at Wellesley College in Massachusetts, and at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, USA. After his return to India in the summer of 2017, he has been working as an independent scholar, and will join the faculty of FLAME University near Pune as associate professor of art history. He emerged as a noteworthy voice in Urdu poetry during the last decade of the twentieth century, and his poems have been published in reputed Urdu literary journals of India & Pakistan. Along with two collections of Urdu poetry, Hindasa Be-Khwaab Raton Ka (2006) and ‘Adam Taraash (2016), as well as a book of translations into Urdu from European poetry, titled Mera Khoya Awazah (2014), he has published a number of articles, and has translated Urdu poetry and prose into English, most of which can be found in the Annual of Urdu Studies. His works in progress – academic essays, personal reflections, poems, translations – center on composite dimensions of literature and culture, as well as art and architectural history. His book manuscript, titled Ornate Visions of Knowledge and Power: the Formation of Marinid Madrasas in Maghrib al-Aqsa, is under review for publication.

———–

More by Riyaz Latif in The Beacon

Reading “At a Window, Waiting for the Starlings”

At a Window, Waiting for the Starlings

Fugitive Shadows: “Banaras” and Other Poems

GHOSTS of MALKAUNS

‘Displeasure of Old Friends’ and other poems

‘ON THE SPIRES OF OUR BREATH’

MIRTH AND THE DUST-CLOUD: REMEMBERING VARIS ALVI

Leave a Reply