Courtesy: Wikipedia

A Preface

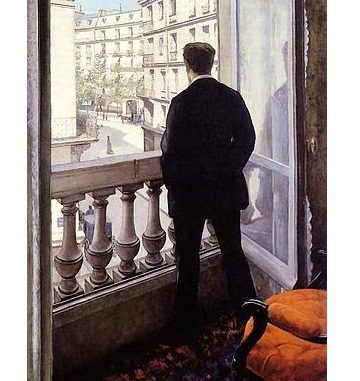

On March 22 this year we featured an essay by Riyaz Latif that, on a surface view is a meditation on gazing out a window; some urban landscapes and then the red breasted rosy starlings that “sketched the skies.” Repeated readings reveal it to be much more, a lyric, an open ended text, an invitation to be read per the reader’s own subjectivities, a textual invitation to a conversation.

From across the world, in Texas, another poet, Asif Raza responded.

We would like to believe that the conversation has started; a conversation that begins in the act of reading, an act that creates its own codes of empathic engagement, a reaching out to another’s subjectivity, a confluence that then creates another text fostering further conversations.

So here’s Asif Raza’s take on Latif’s essay; here’s hoping that others will be encouraged to participate. We believe that the silos of what Latif calls “seething silences” in which we are billeted can be breached. What better way than conversation through reading? And writing.—The Beacon

***

Asif Raza

N

otwithstanding the pain and outrage he feels at the indecencies of the dystopian world that he inhabits, Riyaz Latif makes it clear that his essay At a Window, Waiting for the Starlings is not intended to be an engagement in activism of one kind or another. On the contrary, as he squarely puts it, eschewing any socio-political, cultural or didactic agenda, his purpose is to present to the reader “nothing more than a reflective artifact “of his visual experience. It is not an externally motivated endeavor but one dictated by an inner creative urge ascending from the depths of his being.

Latif’s rueful escape from the disordered and distorted world he inhabits, and his refuge in his “seething silence,” in other words, his retributory rejection of it, and his turning inwards, attests to the fact that an individual’s alienation, isolated consciousness, fragmentation of self, are tropes that have never ceased to represent the angst of self-aware individuals in the technologically advanced postmodern age. Rather, one can assert that under the postmodern conditions, where human subjectivity has come under renewed assault, where the simulated experience has become indistinguishable from the actual so that illusion and reality are no longer binaries, where space has shrunk and time has been dislocated, atomization of self and of experience has rather intensified.

The angst of alienation and loneliness in a disorienting urban world, which lost its horizon of meanings at the outbreak of the industrial revolution, was first given expression to by Baudelaire who holds the canonical status of being “the first urban poet”, in his modern-era- inaugurating, “Flowers of Evil”. The tradition he established was continued after him, among others, by Rilke, Baudelaire’s true heir, who continued the spiritual journey from exteriority to interiority commenced by him. In my view, both Baudelaire and Rilke should help us in providing a frame of reference within which to gain an insight into Latif’s musings.

In this visually intense essay, the physical setting of the narrator (sitting in his chair in an apartment seven floors high), reminds me of the poets’ position in Baudelaire’s “Landscape “in which, ensconced in his attic-chamber, he looks, from high above down to the city beneath his eyes. However, unable to immerse himself in it, he transports himself to his transcendental realm of imagination. As he says with idealistic nonchalance:

“I shall close all the doors and shutters tight,

And build my fairy castles in the night”

And

“………………….in vain

Will Riot below, storm my window pane

To make me raise my head.”

By refusing to confront the world and instead indulging in his “idyllic childhood” musings, the poet turns his attic-chamber into a figure for his interiority. Our narrator’s apartment-room (his equivalent of the poet’s attic-chamber) from which he launches his visual journey may be, by contrast, construed as a figure for his exteriority since, he does not shutter the world out but confronts it (though in the end, as we shall see he too will “withdraw” from his exteriority and move into his interiority, and therefrom, “create” his own transcendental vision).

As he watches from his top down perspective the cityscape down below, his acute self-consciousness is reflected in the way he registers minute details of his material setting and circumstance. As such, he comes across as a being who is trapped in the limits of his physical existence. A window frame affords him a line of sight. But paradoxical as frames are, as Derrida has demonstrated, while it makes his visual experience possible, it delimits it too. Or as he puts it, “it reins you to its sanitized geometry”. That is the frame’s fatality. He might have liked to restrict his vision to the sight of the red breasted starlings descending “onto the tree-tops.” But then, as he admits, “the eye is fated to register much more than the cascading arrival of the red breasted starlings”. So, he surrenders to the physicality of the fact that the eye has its own fatality too.

Starting from the tree tops his gaze stretches in a linear fashion to span the grotesque incongruities of myriad revolting sights testifying to the gross socioeconomic disparities and the moral depravity of the postmodern city, perversely ‘masquerading’ itself as a human habitat. Again, he might have liked to bypass these sights of urban blight. But as he puts it, “such is the fate of vision and the frame: hand in hand, they are unwittingly induced to chisel panoramas of disenchantments.”

Upon reaching the last frontier of his journey of the gaze, that is, a denaturalized postmodern urban horizon, and discovering no coherent vision but only a riot of “intertwining disparities”, he, in muted angst, but urbanely, stages what he calls his “creative withdrawal.” As he does so his gaze registers more sordid images of the hyperreal urban phantasmagoria. Among others, of violence against nature and its degradation: an elephant loitering deracinated, exiled from his natural habitat, attempting a communion not with its own kind but with sands of the river in which no water flows. It is a world that has lost its organic unity and symmetry it once might have had, a devitalized world over which, as Heidegger would say, “Techne” rules and from which “Poiesis” has been eliminated. The only sign that it is a site of a human habitation, as he poignantly records, is the sight of “washed clothes lined up to dry on the river edge.”

He retracts his gaze all the way to the river bed, and from there, to the window frame from which he first unfolded his vision and spotted the arrival of the birds, in unison, over the tree-tops.

In its dialectical movement, his gaze has traversed a circle of futility because at the end of it “all you get is the stillness of the dusty green vegetation awaiting the arrival of the winged legions.” Though the birds are missing, still, as he puts it, you can “set the stage for the verdant arrival of the winged legions” but “only if you disinherit the autocracy of the seeing eyes.” To be able to accomplish that, however, as he reminds you (or rhetorically himself), “You must blur your vision by a fraction”. That is, only by suppressing your vision, by imposing willful blindness on your eyes, and only by filtering or bracketing out the disenchanting world, will you be ready to receive the “fluttering arrival” of the auspicious red-breasted starlings in unison.

By what seems like a brilliant speech act, he paints the picture of the starlings in masterful strokes and in dazzling colors. There is an unspoken contrast drawn between the celestial realm of their flight above, and the devitalized world down below. The starlings fly ebulliently, free, on their own accord, “sketching the sky”. Yet, despite the geometry of their flight assuming myriad complex formations, the ever-shifting contours of their flight, or their “fluid anarchy,” they stay in synchrony; they move as “one being” (as one organic community one might say, that has been lost to man). It is a “flapping organism” in which, the erstwhile disenchanted narrator hears in enchantment, the resonance of “a long- lost poetic heartbeat’’.

The coherence and aesthetic unity that he did not see with his ‘seeing eyes’, the narrator now sees in the birds’ flight. Bur at this point, as I see it, it is not a perceptional experience but a transcendental vision of his inwardness, one unencumbered by the heaviness of the seeing eyes and manifested to his senses seen by his “mind’s eye”.

Baudelaire too, in landscape liberated himself from “the tyranny of the visual” by closing his eyes and not lifting his head up because he firmly believed, that not seeing the world was a prerequisite for attaining a profound vision. But he also realized that such liberation was momentary. The narrator realizes it too, when in the end, despite his willfully blurred vision, he finds himself back again: “delimited to the window frame”.

At this juncture, the narrator invokes the lines from Rilke’s First Elegy. Rilke, who too, like Baudelaire, firmly believed the personal moment of transcendence to be evanescent, illustrates the point by the invoking the figure of circus acrobats (in his Fourth Elegy). After the summersault, an acrobat cannot stay at his apogee, or settle at his moment of perfection, for more than a second. Thereafter, he must fall back to the ground, instantly. The narrator’s rise, like the acrobat’s, too meets its fall, and instantaneously. As he observes, rather plaintively, observing the starlings: “You move fractionally, and they perish in the almost imperceptible delicacy of the gesture”. At that juncture, you must follow the imperative and, as he puts it, “must retract your vision fully back into the eye…” The fatality of the frame, the widow, and the heaviness of sight returns.

In the end, he seems to have come full circle back to his resigned self, acutely conscious of his entrapment into the limits of his physical existence. But, at his juncture, a radical transformation has occurred: having completely withdrawn his gaze and himself from what lies outside the window frame, the inside of the frame becomes a figure of his interiority. But the experience of his interiority is not a pure experience. It is still grounded in the world. One is fated to suffer this duality of the exterior and the interior forever unless it is ended by death whereby the realm of being and nonbeing regain their lost unity.

In the last few lines, with a touch of metaphysical pathos, and in a rather elegiac tone, the narrator seems to take a position that is grounded in monist ontology: life is only an epiphenomenon of matter, merely a play of material interactions that ends with death. And when that fated moment comes “you must relinquish the play of the eyes”.

In his Seventh Elegy, Rilke celebrates the creative potential of the artists and poets for overcoming the duality of the exterior and interior world in this world. It is accomplished by taking the visible world inwards, into one’s consciousness, and transforming its objects therein, into phenomena of one’s mind, into one’s thoughts, which are then manifested to the senses by the poet, in symbols and images, for himself and his reader. By doing so, the poet rescues them from linear time, death and decay to which they are subject in the physical world. This perpetuation of one’s moments of transcendence in poetic language exemplifies human, rather than some mystical or metaphysical transcendence (which he rejects in his Seventh Elegy). One achieves it not by relinquishing the world, but by owning it, by participating in it.

In my view, this essay, with its highly-poeticized prose begs to be labeled as a lyric essay. Its densely textured, evocative and highly sensuous prose (which is though just as cerebral), its figurative thrust, compelling visual images, repetitions, and meticulously chosen words (such that hardly any may be replaceable) are some of the characteristics that, in my view, set it apart from a traditional narrative and bring it close to a prose poem.

By locating himself in the aesthetic realm and writing this lyric essay with the sole purpose of crafting an object of art, or artifact, Latif has realized his personal moment of human transcendence. It is a triumph that is enduring in the Rilkean sense in which a work of art embodied in poetic language is enduring. It is a linguistic conquest whereby Latif succeeds in rescuing his elfin starlings from the oblivion to which we, mired in our quotidian existence with its utilitarian preoccupations, consign them. Thereby, he has succeeded in salvaging “little things” from the ravages of linear time and space, and has poetically preserved them in his interiority where eternity reigns.

******

Asif Raza writes poetry in Urdu and translates many of them into English. His poems have been published in several literary journals in India and Pakistan. Several of his original poems as well as his English translations of them were published in the now defunct bilingual journal, Annual of Urdu Studies, University of Wisconsin. He has authored three collections of poems: Bujhe Rangon ki Raunaq (Splendor of Faded colors), Tanhai ke Tehwar(Festivals of Solitude) and AaeeneKeZindani (Captives of the Mirror) published in two editions, the first one in Delhi, India (under the supervision of Shamsur Rahman Faruqi, who also wrote its foreword) and the other in Karachi, Pakistan. Asif Raza came to the U.S. in 1975 on a fellowship. After a doctorate in Sociology, he taught at the University of Missouri, Columbia, Northern Illinois University, DeKalb and a senior college in Texas. He lives in Tyler, Texas More by this author in The Beacon CONVERSATION WITHOUT MAPS ARCH OF MEMORIES and other poems More by Riyaz Latif in The Beacon

Fugitive Shadows: “Banaras” and Other Poems

GHOSTS of MALKAUNS

‘Displeasure of Old Friends’ and other poems

‘ON THE SPIRES OF OUR BREATH’

MIRTH AND THE DUST-CLOUD: REMEMBERING VARIS ALVI

Leave a Reply