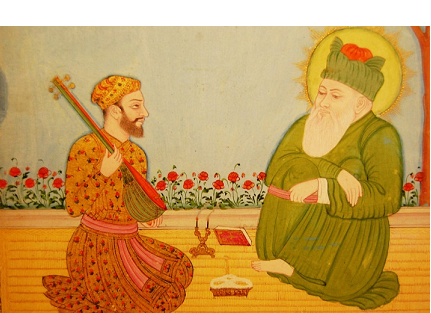

Khusrau with Nizamuddin Auliya. Courtesy: Sufinama

Shamsur Rahman Faruqi

I

t has often been said that the notions of Culture and History are intertwined: one can’t be understood without taking the other into consideration. This does not take away the ambiguities buried in the two terms but does give us a starting point. The term Culture is of more recent origin and has therefore not accumulated the encrustations that the other has accumulated on and around it over time. What makes the term ‘Nation’ more difficult to tackle is its comparatively recent history. Its present meaning, and the aura around it, is the product of European Enlightenment and since European Enlightenment is ineluctably bound up with Colonialism, it follows that as modern terms, ‘Nation’ and ‘Nationalism’ were alien to colonized societies before they were colonized. The colonizer introduced the ideas ‘Nation’ and ‘Nationalism’ into the societies which were brought under his colonialist rule.

Let’s begin with a working definition of the term ‘Nation’. The Oxford English Dictionary should be a good guide to start with. Here’s what it says about ‘Nation’ in its 2009 electronic edition:

“An extensive aggregate of persons so closely associated with each other by common descent, language, or history, as to form a distinct race or people, usually organized as a separate political state and occupying a definite territory…In recent use, the notion of political unity and independence is more important.”

From this follows the concept of ‘The modern nation-state, marked by sovereignty and repudiation of any superior authority.’ But it must be remembered that there were nation-states in the past too, but the notion of an authority, superior to the entity of Nation, was also present. Pre-modern China, for instance, prided itself as being ‘The Middle Kingdom’ and so superior to the rest of the world that for a long time it was illegal to migrate from China to any other country. Even then, the Chinese people and government recognized the moral and ethical authority of Confucius. The notion that one ‘Nation’ has the right to occupy and utilize for its own purpose the space and the resources of another people is purely Enlightenment and is supported in one guise or another by even such eminent Rationalists as Locke, or Hume, or Edmund Burke.

The Eastern peoples, on the whole, didn’t develop the idea of ‘Nation’ and ‘Nationalism’. They understood, historically and culturally, the idea of conquest and annexation. That the heterogeneous peoples whom they conquered could or should be moulded into a ‘Nation’ with a given space and, if possible, language as well, and that all its members should be closely associated with each other culturally was something which didn’t occur in their world-view.

In India, the system of varanas existed before the Muslims and individual Indians were recognized first and foremost as members of a given varana. Much later, the Muslims came to stay, as traders or in military expeditions. They had no caste system, but they readily adopted different kinds of discriminatory social practices imitative of the local practice of distinction among the people by virtue of their ‘caste’, or the accident of their birth. In addition, identifications based on place of origin became prevalent: Iranian, Turk, Afghan, Armenian, so forth. Indian converts to Islam were generally identified as ‘Shaikh’ but many retained numerous topical cultural and symbolic practices of their original milieu. All Muslims, whether local or foreign, adopted or adapted over the years many cultural and symbolic practices from the local populace.

In spite of numerous absorptive or imitative social and religious practices between the practitioners of the two radically different belief systems, all natives of India described themselves as Hindu.

The term ‘Hindu’ was occasionally changed to ‘Hindi’, but the description was non-religious, non-denominational and devoid of any nationalistic or parochial feelings. This state of affairs continued until the middle of the 18th century.

Tek Chand Bahar of Delhi (d. 1766), in his monumental dictionary of Persian language (final recension prepared around 1765), has this to say about the word Hindu (Delhi, Matba’-e Siraji, 1866, Vol. II, P. 770):

ہندو:۔۔۔ساکن ہند۔خان آرزو می فرمایندکہ ہندو قوم مخصوص[است]، و لہـذا بر مسلمانانے کہ ساکن ایں ملک اند،اطلاق آں نمی تواں کرد۔ (بہار عجم، ص770)

Hindu: …Resident or native of India. Khan-e Arzu commands that ‘Hindu’ is a specific community (qaum):the term should not be applied to the Muslims native of or resident in this country.

Bahar goes on to say that according to Khan-e Arzu, use of the word ‘Hindu’ instead of ‘Hindi’ for any Indian is endemic, and is because of taghlib تغلیب. Now the term تغلیب is applied in grammar to a state where the strong is able to overcome the weak. Thus, even according to Khan-e Arzu, the word ‘Hindu’ meant ‘Indian’ in standard parlance

How the term ‘Hindu’ became applicable to the Hindus alone is a long and complex story. But one thing is certain: Khan-e Arzu enters the story in mid-eighteenth century by which time many English practices and notions, especially notions about identity based on Nation and Religion were becoming common in India.

First, the English introduced the word ‘Gentoo’ in their language, to mean a Hindu, or a non-Muslim. Since Judaic culture admits only of ‘Jew’ (=A person of Hebrew descent, one whose religion is Judaism) and Gentile (=Of or pertaining to any or all of the nations other than Jewish), and since early European traders always inquired about a person’s religion, and since they learned that there were Indians who belonged to a non-Judaic (Gentile) order of religion, they combined ‘Hindoo’ and ‘Gentile’ and produced the word ‘Gentoo’.

Here’s what the OED tells us about the meaning of the word ‘Gentoo’:

Gentoo: A non-Muslim inhabitant of Hindustan; a Hindu; in South India, one speaking Telugu…

Three hundred slaves, whom the Persians brought in India; Parsees, jentews…and others (1638).

The inhabitants of the Island…were all Gentows, or Gentiles(1727).

This, then, is the basis of the classification of the Indian people by religion: some were Muslim, others were Gentoo. And here is the OED definition of ‘Hindu’:

Hindu : An Aryan of Northern India (Hindustan) who retains the native religion (Hinduism)…Hence, anyone who professes Hinduism. The King of Cambaya, who was a hindoo, or Indian, that is, pagan (1662). Thus the ‘native religion’ of the Indians was determined as ‘Hinduism’.

Khan-e Arzu was an extraordinarily perceptive linguist and lexicographer. He could see the change that was creeping into the Indian culture by the advent of English ideas. Tek Chand Bahar was not alone in not recognizing the impending change. Nor were the Urdu poets. Barring a few expressions of disdain for the ‘whites’ (the goras) whose colour and deportment were regarded as unattractive, if not exactly repellent, there is almost no mention of Europeans as individuals or as members of a class in 18th century Urdu literature.

Among the outstanding Urdu poets of the 18th century, Sauda died in 1781; Jur’at died in 1809; Mir went soon after, in September 1810. Sauda in Delhi and Jur’at and Mir in Lucknow do not have anything to say about the European. Jur’at has one famous ruba’i, which is more an indictment of the Navabs and dandies of Lucknow-Faizabad whom the poet sees as puppets, or talking birds caged by the English:

سمجہے نہ امیر ان کو کوئ نہ وزیر

انگریز کے ہاتھ اک قفس میں ہیں اسیر

جو کچھ وہ پڑھائیں سو یہ منھ سے بولیں

بنگالےکی مینا ہیں یہ پورب کے امیر

Let none imagine them to be Emirs or Viziers

They are in a cage, put there by the English

They talk what the English teach them to utter

These Emirs of the East are indeed mynas of Bengal

The word that I translate here as ‘East’ is purab in the original, which signifies Awadh for the poets who came to Lucknow from Delhi. As we can see, the poem is more an accusation of powerlessness against the grandees of Awadh than a criticism of the foreigner. Possibly it was composed after 1797 when Asafuddaulah died and the English ousted his son and successor Vazir Ali Khan from the position of Navab and installed Asafuddaulah’s stepbrother Sa’adat Ali Khan in his place.

Insha (d. 1817) has occasionally some satirical or derisive she’r against the English, but apparently there is no consciousness of the anomaly prevailing in the situation where a handful of apparently uncouth foreigners were well on way to ruling the country. For example:

غلام میں تو ہوں ان صاحبوں کی کھڑ پچ کا

ا گچ کا سڑی تو صاحبی اس پر چبوترI am really slave to the cantankerousness and iltemper of these sahibs,

Their sahibi is rotten, of no good, and they lord it over

from their raised platform of mixed mortar.

Shaikh Ghulam Hamadani Mus.hafi (1750-1824) is one poet who was conscious of the dire change that augured no good for the country. He responded to the change in three different ways:

- The large scale rapacity and the organized pillage practiced by the English which was clearly leading to the economic doom of the land.

- The meanness and the small mindedness of the English in dealing with the Indians.

- The Machine-like, soulless organization of the English regime and the transfer of de facto power from Delhi to Calcutta [now Kolkata].

- The growing military and social influence of the English hurting the Indian identity and the Indian ethos.

In modern times, these reactions would count as nationalistic and anti-imperialist. In Mus.hafi’s day, there was no nationalistic consciousness, but the distress caused by conquest and a pervasive foreign presence and the alien ness of the conqueror’s mores was apparent to most, if not all Indians. From about 1796, the stark reality of economic and political loot as it unfolded over the next three decades begins to be reflected in Mus.hafi’s poetry:

ھندوستاں میں دولت و حشمت جو کچھ کہ تھی

ظالم فرنگیوں نے بہ تدبیر کھیںچ لی ( سوم)

Whatever wealth, whatever pomp there was in India,

The tyrannous Firangi pulled it out by stratagem (Divan III, circa1796)کلکتے سے خفا تھا دل مصحفی کا یارو

جب تو چلا گیا وہ دکھن بغیر پوچھے (سوم)

Mus.hafi’s heart was aggrieved with Calcutta, dear friends,

Is that not why he went off to the Deccan without being asked? (Divan III, circa 1796)

There’s no evidence that the poet ever went to Calcutta, or the Deccan. This she’r expresses his resentment of the English regime at Calcutta, and his hope that the order of things in the Deccan would be different. Most likely ‘Deccan’ here refers to Tipu Sultan’s Mysore whose state was finally demolished and devoured by the English in 1799. This reminds one of the much later, and tragic cry of Bahadur Shah Zafar:

اعتبار صبر و طاقت خاک میں رکھوں ظفر

فوج ہندستان نے کب ساتھ ٹیپو کا دیاPrecious little trust can I have, oh Zafar, in my fortitude and strength

Did the armies of Hindustan ever stand by the side of Tipu?

Here is Mus.hafi lamenting the organized and the quietly legalized way the English went about doing their deleterious deeds. This obviously contrasts with the disunity among Indian nobles and the disarray of their armies:

ہاتھ سے گوروں کے جانبر ہوویں کیوںکر اہل ہند

کام کرتے ہی نہیں ہرگز یہ بن کونسل کۓ (چہارم)How can the Indians ever save their lives from the

grasp of the white man?

They don’t do a thing without convening their Council (Divan IV, around 1796)

An interesting cultural insight into the ways of the English: their women not only go out unveiled and in full make up, they also indulge in such mundane if not vulgar activities as bidding at a public auction. The English are light of colour, but are vapid and uninteresting. They pretend to be people of the scientific temperament and believe that their systems—including that of healing and curing—are better than those of the others. I give all the she’rs together below:

میاں مصحفی لیلام میں کل ہم بھی گۓتھے

کر آۓ ہیں اک طرفہ فرنگن کا نظارہ (چہارم)Hey friend Mus.hafi, I too went to see the auction

yesterday,

Well, I certainly observed to the full the delightful sight

of a firangi woman (Divan IV, around 1796)ہے یہ فلک سفلہ وہ پھیکا سا فرنگی

رکھتا ہے مہ و خور سےجو پاس اپنے دو بسکٹ (ہفتم)

The mean tempered heaven is that light coloured,

vapid firangiWho has nothing but two biscuits—the sun and the

moon (DivanVII, circa 1820)زخم شمشیرنگہ حیف کہ اچھا نہ ہوا

کرنے کو اس کی دوا ڈاکٹر انگریز آیا (ہفتم)

How sad, the poor fellow who was wounded by the

sword of the beloved’s glance never recovered,

An English doctor was brought to treat him

(Divan VII, circa 1820)

The innuendo here is manifold: He who is wounded by the beloved’s glance can never get well; even an English doctor couldn’t do much for him; the Englishman may claim to be the maximum healer, but he is no good, really; finally, maybe it was perhaps the English doctor’s ministration that killed him off!

We now look at two she’rs which are withering in their condemnation of English military-political tactics:

مالک الملک نصارا ہوۓ کلکتہ لے

یہ تو نکلی عجب اک وضع کے جنجال کی کھال (ہشتم)

The Christians became God almighty, masters of all

land from Calcutta

Indeed, that turned out to be a strange kind of deep

trench—messy and unfortunate(Divan VIII, 1820-1824)توڑ جوڑ آوے ہے کیا خوب نصارا کے تئیں

فوج دشمن سےوہیں لیتے ہیں سردار کو توڑ (ہشتم)

How nicely have the Christians mastered the art of

breaking and patching!

Right there in battle, they bribe and win over the

enemy’s commander (Divan VIII, 1820-1824)

Echoes of Sirajuddaulah’s Mir Ja’far, of Tipu Sultan’s Mir Sadiq, and perhaps some other, minor ones, forgotten by history, can be heard here loudly.

Mus.hafi’s ideas clearly reflect the perception that the English are interlopers. In all the she’rs that I quoted above, there is a strong sense of Indian or Indo-Muslim identity against a foreign and threatening identity. The English are not only outsiders: they are occupying powers. But Mus.hafi was not just political. Much can be found in his poetry where the distinct sense of a cultural identity also impinges upon his day to day observations.

Yet it must be remembered that the term ‘Culture’ as we understand it today, is again a post-enlightenment concept. From its original meaning of ‘cultivating the soil’ to the modern, somewhat trendy perception of ‘culture’ as something which cultivated people possess, is a far cry. Words which we today use for ‘culture’, like saqafat, tahzib,were not known in pre-modern Urdu. What was known and admired was ‘way of life’. Each people had a way of life. A famous line of Nizamuddin Auliya as capped by Khusrau comes to mind:

ہر قوم راست راہے دینے و قبلہ گاہے

ما قبلہ راست کردیم بر طرف کج کلاہے

Each community has a way, a path of life, and a

direction in which to pray

‘I chose my right direction facing which I pray—

It’s one who wears his cap askew.’

As we all know, the first line was reportedly spoken by Nizamuddin Auliya sahib; the second line was an impromptu response by Khusrau, and the two lines embody an extremely concise description of what pre-modern Indians would define ‘Culture’ if there were such a word in their vocabulary. Pre-modern Urdu writers didn’t write a treatise on culture: they lived it. It was a belief system which trumped religion (witness Khusrau saying that he prays not in the direction of the Ka’ba, but in the direction where Nizamuddin Auliya sahib is); and Nizamuddin Auliya freely recognizing the right of each and all communities to have their ‘way’, their ‘path’ (or dharma), and a direction facing which its people pray.

Thus culture in pre-modern India was, and in many ways still is, a set of symbols rather than a set of eschatological doctrines about life, and God, and death and judgement. Culture is not something ratiocinative, or something that is organized rationally. Shaikh Bajan, Fakhr-e Din Nizami, Shaikh Khub Muhammad Chishti, Muhammad Quli Qutb Shah, the earliest of the Urdu poets from the fifteenth century were as much comfortable with the use of Hindu or non-Islamic imagery in their Islamic religious poetry and prose as they were familiar with their own religious and spiritual traditions.

Over time, Urdu literary practices assimilated, or at least adopted freely and took advantage of mixed culture literary and social symbology. For instance, we have the belief that Sri Krishn was dark complected and that’s why he’s always imaged as blue in face and body. Then we have the river Jamna whose water has a faint green-blue tinge which can be seen distinct from the water of the Ganga at the confluence of the two rivers. Now here is Nasikh (1773-1838) combining the two themes to create a new image:

اشنان کشن جی نے کیا ہے جو مدتوں

اب تک اسی اثر سے ہے رنگ جمن کبود (دوم)Krishnaji has bathed in its waters for ages

And that’s why the waters of the Jamna still are

blue in tint (Divan II)

Let’s now look at Nasikh again, using the symbology of the Ganga for his own purposes:

ہوۓ ہیں عکس فگن میرے داغ گنگا میں

کہاں بہاتے ہیں ہندو چراغ گنگا میں

ادھر بہاتے ہیں گل اور ادھر نہاتے ہیں گل

ہر ایک صبح شگفتہ ہے باغ گنگا میں

کمند موج جو مانند زلف ہے دلکش

ہوا اسیری غم سے فراغ گنگا میںThe red scars of my heart are reflected in the Ganga

It’s not that the Hindus float lamps in the Ganga

On one side, they float flowers; roses bathe on the

other,

Every morning, a garden blossoms in the Ganga

The waves tug at my heart with their lassoes, beautiful

like her tresses

I found release from the chains of sorrow in the Ganga

(Divan I)

Writers in languages like Urdu don’t need to make statements about culture: their poetry is their statement. Yet it is true that with the passing of time and the resultant accumulation of complexities, culture takes on more and myriad meanings. For instance, it is the general view now that culture is the intellectual side of civilization. This opens up some possibilities for refinement.For instance, scientist-writers like C. P.Snow asserted that traditional culture is mainly literary and does not like to change too much, while scientific culture is responsive to new intellectual developments;it is expansive and not restrictive. Such refinements—more like assumptions, rather—are too general.

Other refinements being suggested now in our country seem to be more chauvinistic than philosophical. In fact, it is not complex learned behaviour or pseudo-historical attitudes to life that constitute culture, any kind of culture. It is the social, political and traditional past and present of a people that make a culture. Culture thrives on symbolism, and Urdu literature symbolically expresses all sides of Indo-Muslim culture.

History is a learned subject and that’s why Persian, sometimes Arabic, was the usual medium for it in pre-modern times. That’s why early Urdu has very little historical literature. Short, limited histories in Urdu begin to appear in the North by the 1770’s, but there was no independent discipline of history in Urdu before the 19th century. And that is the reason why historical writing in Urdu has been so heavily slanted toward the assumptions and the imperialist intellectual policies of the colonizer.

Our early accounts of our literature declare articulately as much as inarticulately that Urdu literature was, with rare and perhaps accidental exceptions, uniformly bad. It did not reflect ‘life’ or ‘nature’ as they really were. Much of the blame was, perhaps unconsciously, reflected from the colonialist version of the history of India in the 18th century. According to the comprador or colonial views of the 18th century, there was all-round decline in India at that time: a vacuum appeared in law and governance, so the English stepped in to fill the vacuum. Maulavi Zakaullah’s History of India, and on a lesser scale, Naval Kishor’s History of Awadh are examples of such history writing. They don’t actually state that the advent of the English was just the operation of a natural law. But they clearly imply this.

Even Syed Ahmad Khan Bahadur, in his date-list of rulers at Delhi, took pains to insert George III and his successors alongside Shah Alam Bahadur Shah II and his successors. It was if the Mughals had already ceased to exist, or that they were non-entities. It is interesting to note that though George III ruled from 1760 to 1820, Syed Ahmad Khan showed the duration of his reign as seventeen years, implying that he became King of Delhi-India in 1803, the year the English defeated Scindhia and the Mughal army in the battle of Delhi and installed a resident at the Emperor’s court. Perhaps it was from that time that public proclamations went like this:

ملک خدا کا سلطنت بادشاہ کی حکم کمپنی بہادرکا

The land belongs to God, the rule is of the King,

the writ is that of the Company Bahadur

While mainline historiography in India and abroad has to a certain extent ameliorated the wrongs done to the 18th century of our history by European historians and their collaborators, our literary history continues to sing the same old tunes: The 18th century was a time of chaos; Mughal power had ceased to exist; Delhi had been ravaged and savaged by the Afghans and others so that it had become a wilderness; the literary culture was effete, the language needed ‘reform’; the poets, all followers of the ‘pernicious movement’ ofīhāmgo’ī(indulging in wordplay) were writing trash in the name of poetry; their poetry was not ‘natural’, they knew nothing of ‘nature’, and so on.

Our literary historiographers taught us that since the word ‘urdu’ means ‘army’, our language is named Urdu because it was the product of invading armies who were obliged to interact with the local populace, and thus was born the language called ‘Urdu’. Our generalizing historiographers created, or imagined, ‘two schools’ of Urdu poetry and located them in Delhi and Lucknow. Thus was born the fiction of ‘Dihlavi’ and ‘Lakhnavi’ styles of Urdu poetry, and the proposition that while the Dihlavi style poets were complex, inward-looking, not given to the physicalizations of love, the Lakhnavi style poets were more or less the opposite of Delhi. Force of events has all but exploded the fiction of Two Schools, but we still talk of Dihalaviyat (Delhi-ness) and Lakhnaviyat (Lucknow-ness) in poetry.We still believe in what our 19th century forebears learned in their school and at best early college days: ‘Poetry is the spontaneous overflow of the powerful feelings of the heart.’ We airily dismiss much of our pre-modern poetry and creative prose as unrealistic and therefore valueless because they don’t conform to the Wordsworthian doctrine, a doctrine, one is compelled to say, long abandoned in the West from where our Victorian ancestors adopted it reverently and passed on to us.

On the academic and popular level, and perhaps even on the intellectual level, our literary historiography and therefore our understanding of our literature, are still mired in the primitive understanding of our literature that is essentially based on 19th century English assumptions. Fortunately, our cultural consciousness and our identity as Indo-Muslims are still largely intact.

But for how long? Then we had the foreigner to blame; now we have none but ourselves.

*******

Notes. The main visual is a photograph of a scene from Ramayana as part of Mughal miniature paintings commissioned by Emperor Akbar in the 16th century. This photograph courtesy Wikimedia Commons. Keynote Address by the author at Anjuman Taraqqi Urdu (Hind), New Delhi, March 15,2018: “Urdu Writing over Two Centuries on Nation, j History, Culture: 1800-2017” Many thanks to Mr. Faruqi for permission to use text. Some stylistic changes have been made in the text that is otherwise unaltered.

Shamsur Rahman Faruqi Urdu poet literary critic, novelist, in short a polymath whose contribution to Urdu literature and to Indian letters has been immeasurable. His historical novel Mirror of Beauty, self-translated from Urdu original sheds light on a historical period much abused by conventional (colonial) historiography.

Also read:

Leave a Reply