Jan Sahas

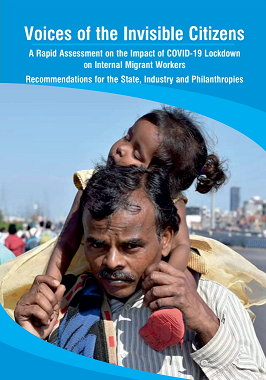

“Forget COVID. We will die of hunger first.”

[Excerpts from the report]

Introduction

![]() A staggering 77% of India’s workforce (3 out 4 workers) falls under the category of vulnerable employment (World Bank, 2019). One of the largest and most vulnerable workforces of India are seasonal migrants – workers who migrate temporarily. Providing informed assessments or drawing strong conclusions about migrant workers is difficult because of data constraints. Figures for seasonal migrants vary from 15.2 million[1] to 55 million[2].

A staggering 77% of India’s workforce (3 out 4 workers) falls under the category of vulnerable employment (World Bank, 2019). One of the largest and most vulnerable workforces of India are seasonal migrants – workers who migrate temporarily. Providing informed assessments or drawing strong conclusions about migrant workers is difficult because of data constraints. Figures for seasonal migrants vary from 15.2 million[1] to 55 million[2].

The increase in migration globally has been traced back to the widening gap between agriculture and non-agriculture sectors along with the growth in unequal distribution of resources and economic opportunities across regions. The scenario is not different in India, as seasonal migration is largely distress driven – geographically, they are from rain-fed agriculture areas and majority of them are landless or small/marginal farmers who have no livelihood opportunities available post the kharif crop harvest. Seasonal migration is often a response strategy to this crisis of lack of job opportunities and the need to earn basic income for subsistence. These migrants are more likely to be socially deprived and poor while having obtained little to no education, with minimal or no assets. Seasonal migrants, thereby, are placed in a situation where they become extremely desperate to find employment and migration provides them with greater economic prospects, which in turn provides sustenance to the workers and their families. However, it exposes these individuals to harsh and vulnerable situations where work and living conditions are extremely poor[3]. The vulnerability of migrants is compounded by their caste identity with majority of them belonging to categories such as Other Backward Castes, Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribe, as caste determines ability to accumulate wealth, income and remittance level.

In the case of seasonal migration, it is seen that most often the whole family migrates along with the labourer. These families are likely to be deprived of social security benefits that are provided by the state. The non-portability of entitlements and lack of a centralised system in India means that migrants have to forgo the facilities of the public distribution system (PDS) in destination states. In this entire process, the lives of migrant workers’ children are most adversely affected. They often have no access to continual education due to the constant movement between source and destination locations – which is a disturbing lacuna given the linearity between out-of-school status and instance of child labour[4]. Furthermore, short-term migrants also face issues in effectively engaging in politics and there is suggestive evidence that voter turnout is lower in states with higher rates of migrations[5].

The aforementioned challenges that migrant workers and their families confront are comparable across sectors that employ them. A major section of seasonal migrants is involved in construction (37%), agriculture (21%), and manufacturing (16%) work. Construction sector employs the highest number of migrant workers across India with 55 million daily-wage workers and contributes around 9% to the country’s GDP.Every year around nine million workers move from rural areas to urban cities in search of work within construction sites and factories alone[6]. Therefore, the focus of this report will be migrant workers engaged in the construction industry given the industry absorbs a significant share of the country’s internal migrants, and thereby play an important role in determining the trends of seasonal migration.

Migrant Labour Under COVID-19

The effect of the countrywide lockdown on daily wage workers has been catastrophic in the short term and as time passes, we will learn further about the long-term effects it will have on them. Industry shutdown has rendered workers unemployed across the country. The sudden announcement of the lockdown denied migrant workers particularly the opportunity to collect their wages or make arrangements for leaving cities. During this crisis, transportation facilities have also been locked down as a result of which migrants are now trapped in destination cities with not enough resources to tide over the situation without the ability to pay rent and maintain physical distances since they typically live in very small rooms which they share with several others. Migrant households currently face the risk of hunger, poor or no access to hygiene and consequent health issues.

![]()

Rational of the Study

Given migrant families are marked by distress and poverty, which are important causal factors for seasonal migration, it is imperative that we understand the impact that a country-wide lockdown will have on seasonal migrants in both the short and long term. Public intellectuals, academics and civil society organisations have repeatedly questioned the inadequate preparation by the State and sudden announcement of extreme measures without consideration for socio-economically weaker sections. It is understood that the vulnerability and marginalisation of this population will only worsen as the lockdown progresses, if they are not provided direct assistance.

Since the lockdown, the central government has announced several welfare measures for those whose lives have been severely impacted by the lockdown. Although the welfare measures taken have been a welcome step towards the right direction, the true effectiveness of these schemes in responding to the crisis can only be witnessed over time. ![]() However, it is important to note here that the announced measures still largely fail to address the concerns of the many daily wage migrant labourers who are either stuck in destination sites without employment or access to PDS entitlements in cities or labourers who do not have adequate ration in their own villages. Media reports from across India have highlighted the loss of livelihoods and income of seasonal migrants.

However, it is important to note here that the announced measures still largely fail to address the concerns of the many daily wage migrant labourers who are either stuck in destination sites without employment or access to PDS entitlements in cities or labourers who do not have adequate ration in their own villages. Media reports from across India have highlighted the loss of livelihoods and income of seasonal migrants.

In these challenging times, a rapid assessment of the impact of COVID-19 lockdown measures and the consequent loss of livelihood on seasonal migrants become further more important to ensure their needs and concerns are heard.

Jan Sahas has been closely working with more than 1,20,000 migrant workers, particularly construction workers and other vulnerable communities. This active community helped us in reaching out to 3196 migrant families from the construction sector.

Study Objectives

To understand the immediate impact of COVID-19 lockdown and needs of migrant workers and their families.

- To analyse the economic impact of the sudden loss of employment on migrant families.

- To understand access to essential services such as healthcare, public distribution systems (ration), banking, etc.

- To document their self-assessment of the long-term impact of the shutdown, their strategies to cope with the same and expectations from the State.

- To analyse the effectiveness of the current schemes and measures taken by Central and State governments of Delhi, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh to aid migrant labourers.

To provide strategies and recommendations on the way forward

Methodology

Rapid assessment has included both primary and secondary sources of information.

Secondary review: Completed a rapid desk research of both existing and the newly-announced schemes as a response to the impact of COVID-19, which is of relevance to migrant families.

Primary research: We utilized a mixed-method approach for this study.

- Quantitative Research: We carried out a phone-based quantitative survey between 27-29 March 2020. Our 40-member surveyor team reached out to workers through phone calls and entered data using Google forms. Since we were unable to reach workers directly because of the lockdown, we decided to use technology in reaching them. Our existing database of approximately 60,000 workers helped in carrying out this exercise seamlessly. This dataset is part of an ongoing study on longitudinal migration tracking (January 2019 to October 2020)

- Sample Size: 3,196 workers (target sample size 5,000 workers)

- Sampling methodology: The survey team was provided a sample of 6000 workers (we have often observed in the past that phone numbers are sometimes unreachable or barred, hence we provided a much larger dataset to surveyors). This sample of 6000 respondents was randomly selected from a subset of our dataset of 60,000 workers – in which workers had informed us that they had recently migrated (in the last 1-2 months).

- Demographic details: All respondents of this survey are engaged in the construction industry.

a. Age: 18-30 years: 1749 workers (54.7%)

31-60 years: 1428 workers (44.7%)

Above 60 years: 19 workers (0.6%)

b. Gender: Men: 3038 (95% approx.)

Women: 157 (4.9% approx.)

Transgender: 1

c. State: Madhya Pradesh: 1974 workers (68% approx.)

Uttar Pradesh: 1169 workers (36% approx.)

Delhi: 8 workers (.25%)

Other States: 45 workers (1.4% approx.)

d. Number of dependents: 362 workers had 1-2 dependents (11.3%)

1739 workers had 3-5 dependents (55.4%)

1049 workers had more than 5 dependents (32.8%)

46 workers mentioned they did not have dependents (1.43%)

- Qualitative Research: We carried out brief telephonic interviews with 5 workers and their families, who had called into the Jan Sahas helpline or had requested us for help during the survey. We also interviewed our helpline and response team who provided their inputs regarding the situation on ground. There were two main reasons to carry out these interviews:

- Firstly, we felt the need to qualitatively capture the fears, apprehensions and sense of devastation of workers in the innumerable calls that we received.

- Secondly, given the fast-changing dynamics on the ground, many of the survey questions quickly became redundant and the need was felt to understand a few important aspects in detail, for instance, the situation of workers stranded in transit.

Main Findings

![]() Anguish, helplessness and desperation – largely define the distress calls we received in the Jan Sahas helpline (about 12000 cases from 20-31 March 2020) and during the rapid assessment survey (more than 300 cases from 27-29 March).

Anguish, helplessness and desperation – largely define the distress calls we received in the Jan Sahas helpline (about 12000 cases from 20-31 March 2020) and during the rapid assessment survey (more than 300 cases from 27-29 March).

A majority of the labourers were trying to return to their homes walking hundreds of kilometres, as they had little to no cash or food supplies left with them combined with an uncertainty of when they will be able to earn something for their sustenance. Labourers with dependents back in the villages expressed their worry about children, pregnant women, sick, elderly, and disabled members of the household who would be most affected, as they have been unable to send any form of remittances to the dependents back home. We also received multiple calls from villages in the Bundelkhand area about not having access to ration.

This also is reflective of the extent of how much migrant workers are excluded from the social mainstream and ![]() deprived of the means of living during such times of crisis. Although state authorities, civil society organizations and collectives are attempting to provide immediate relief to migrants stranded with little to no resources in the destination sites and source locations, we cannot overlook the long-term impact of the crisis.

deprived of the means of living during such times of crisis. Although state authorities, civil society organizations and collectives are attempting to provide immediate relief to migrants stranded with little to no resources in the destination sites and source locations, we cannot overlook the long-term impact of the crisis.

This analysis attempts to provide a rapid assessment of the ground realities to better inform policies and provide action-oriented steps towards mitigating the crisis. In this chapter, we have attempted to analyse measures taken across three major themes: Income, Ration and Support.

The first theme deals with the impact of loss of wages due to sudden unemployment on the already impoverished migrant households, and discusses critically the existing and newly announced schemes that provide financial assistance to the poor. The second theme seeks to explore the implications of the lockdown on the labourers’ food security, specifically in relation to their current unemployment, potentially for the next 3 to 4 weeks. Additionally, this section sheds light on the existing schemes and the newly announced schemes that ensure supply of ration to the beneficiaries. The third theme of support services examines the immediate government directives and state welfare measures taken to address the problems of shelter, transport, health, and sanitation that migrant workers are facing under a nation-wide lockdown.

The following findings are from a combination of critical analysis of government schemes and two different sources of data:

- Existing Jan Sahas database (about 60,000) of migrant workers in the construction sector.

- Rapid assessment survey conducted – 3,196 migrant workers.

- Brief interviews with 5 migrant workers and their families.

“How long can volunteers and charity groups sustain us?” Saurabh, a migrant worker in Madhya Pradesh.

Income

As part of our survey, one of the workers we reached out to was Saurabh. Along with a group of 16 people (including 5 women and 6 children), he was stranded and starving near Badshahpur (Haryana), which is around 15 kilometres from Gurugram, without any food or essentials. All of them were construction workers from Madhya Pradesh, who have been without work since 22 March, 2020. Usually paid on a weekly basis, none of them were paid wages for their last week’s work which was abruptly interrupted by the lockdown. Left with no money or food, Saurabh was requesting for any possible help. At the time of writing this report, Saurabh’s group has received some rations through the intervention of a citizen volunteer group and a kind-hearted policeman at Badshahpur. The question he posed to us as we ended the call was, “How long can volunteers and charity groups sustain us?”

Saurabh’s experience is reflective of the current condition of most workers in the construction sector. Having to find sustenance by working in one of the most exploitative and informal sectors, the sudden lockdown will push these workers further to the margins. Saurabh’s question urges us to take a look at how a large number of citizens of this country are being denied their right to live with dignity and instead depend on charity to stay alive.

General Findings

It is a known fact that migrant labourers in the construction sector mostly lead a hand to mouth existence. Owing to the highly informal and exploitative nature of the sector, labourers are most often paid much below the minimum wage rates prescribed by the local administration. Delay in wage payment, non-payment of wages and arbitrary wage fixing are common practices, which marks the precarity of every labourer who depends on the sector.

The prescribed minimum wages for Delhi are `692, `629 and `571 for skilled, semi-skilled and unskilled workers, respectively[7]. A simple comparison to the current survey demonstrates that at least 55% of migrant workers are ![]() severely underpaid – about 55% labourers we reached out to reported that they earned anything between `200- `400 on days they worked while 39% labourers earned between `400-`600, and about 4% reported earnings above `600 (per day). A positive trend is that a significantly small number of labourers reported that they earned less than `200 in a day.

severely underpaid – about 55% labourers we reached out to reported that they earned anything between `200- `400 on days they worked while 39% labourers earned between `400-`600, and about 4% reported earnings above `600 (per day). A positive trend is that a significantly small number of labourers reported that they earned less than `200 in a day.

An estimation and cross-comparison of average wage and number of days of work lost demonstrates that the estimated loss of income is between `4,000 to `10,000 per labourer. A significantly disturbing data point that emerged from the rapid assessment survey is that 92.5% of labourers have already lost work ranging from one week to three weeks.In a few calls we received, workers reported that they were evicted from their informal settlements or labour camps, and have been either unpaid or abandoned by their contractors, leaving them with no means for sustenance. Each day of unemployment means absolute loss of wages for every labourer and given the abrupt disruption of employment and the exclusion of migrants from social security measures provided by the state, the migrant households, if they have not already managed to return to their native regions, would have little means to survive the 21 days.

A related point to note is the number of dependents the breadwinner has to support. The rapid assessment survey ![]() reveals that around 54% support 3-5 people while 32% support more than 5 people. This is further reinforced by Jan Sahas’ existing database of migrant labourers in Delhi that places the average number of dependents per worker at 4. If we are to read the data on the number of dependents and wage level together, we can estimate the gravity of the economic burden borne by each labourer.

reveals that around 54% support 3-5 people while 32% support more than 5 people. This is further reinforced by Jan Sahas’ existing database of migrant labourers in Delhi that places the average number of dependents per worker at 4. If we are to read the data on the number of dependents and wage level together, we can estimate the gravity of the economic burden borne by each labourer.

Our survey also tried to understand the burden of debt on each labourer. However, taking into account our learning that most often migrants are not comfortable disclosing details about debt, and that severity of debt bondage and related issues is lesser in the construction sector when compared to the agriculture sector, this was not a compulsory probe[8]. Even then, around 984 labourers (about 31%) confirmed that they had taken loans from either banks, moneylenders, contractors or other sources, out of which 84 (about 8%) labourers mentioned they had loans from multiple entities. Although the amount of debt varies from a few thousands to more than Rs 50000, in the current situation of loss of wages for an indefinite period, the repayment of debt will turn out to be an added burden on the household.

More than 79% (774 out of 984) of the total labourers believed that they would not be able to pay off ![]() their debts in the recent future and around 146 mentioned that they didn’t know how it would affect them. A disturbing fact is that close to 50% of the labourers who had taken debt fear that their inability to pay can put them in danger of some kind of violence. This further emphasises the need for the government to ensure its income support schemes urgently reach those eligible.

their debts in the recent future and around 146 mentioned that they didn’t know how it would affect them. A disturbing fact is that close to 50% of the labourers who had taken debt fear that their inability to pay can put them in danger of some kind of violence. This further emphasises the need for the government to ensure its income support schemes urgently reach those eligible.

Further, we also wanted to understand workers’ plight in the case of a potential extension of the ![]() lockdown and when asked how long they would be able to sustain themselves and their families if the lockdown continued beyond 21-days, a significant 66% mentioned they will not be able to manage beyond a week and 22% households mentioned they can manage for a month.

lockdown and when asked how long they would be able to sustain themselves and their families if the lockdown continued beyond 21-days, a significant 66% mentioned they will not be able to manage beyond a week and 22% households mentioned they can manage for a month.

In the absence of any alternate means to earn a livelihood or provision of accessible welfare/ supportive schemes, these households will face a major crisis that will inevitably lead to starvation, malnutrition, illnesses, debt bondage or inability to admit children in schools in the subsequent academic year.

[Editor: The report lists and analyses union and state government schemes but as it notes apropos the non-termination policy adumbrated by the Centre:]

“Further, the directive also advised all public and private establishments to not terminate their employees, especially the casual or contractual labourers or reduce their wages. Even if the place of employment is deemed non-operational, the employees are to be considered on duty and paid without any deduction of wages. However, there is no mechanism that monitors the job status or change in wages of the employees, especially of casual and contractual labourers, which is evident by the overwhelming figure 90% labourers (approx.) have already lost their source of income in the last 3 weeks. “ [Emphasis in original]

Rations

General Findings

![]() In an effort to understand the current condition in terms of having sufficient ration – close to 40% mentioned that they can sustain themselves for the next 2 weeks and 18% stated that they can sustain for the next 2-4 weeks. However, it is important to note that an alarming number of workers – 1,352 workers – that is 42.3% workers stated that they do not have any ration left for the day, let alone for the next few days. Further, we asked our workers the main obstacles they faced in not being able to buy or access ration – about 33% workers mentioned they did not have the money to buy it, 14% mentioned that they did not have ration cards and about 12% mentioned that they could not access it in their current location as they were migrants.

In an effort to understand the current condition in terms of having sufficient ration – close to 40% mentioned that they can sustain themselves for the next 2 weeks and 18% stated that they can sustain for the next 2-4 weeks. However, it is important to note that an alarming number of workers – 1,352 workers – that is 42.3% workers stated that they do not have any ration left for the day, let alone for the next few days. Further, we asked our workers the main obstacles they faced in not being able to buy or access ration – about 33% workers mentioned they did not have the money to buy it, 14% mentioned that they did not have ration cards and about 12% mentioned that they could not access it in their current location as they were migrants.

The aforementioned conditions reveal the existing precarity that daily-wage labourers and their families experienced after the abrupt lockdown that has clearly put the lives of millions of workers in jeopardy. As mentioned in the previous section, lack of livelihood for more than 3 weeks along with an average of 3-5 dependents to feed has led to genuine fears of dying from starvation before the virus can potentially harm them. According to labourers’ own accounts, there is a sheer absence of basic resources – food and water-for them to survive even for another day.

Workers state that while they are aware of the dangerous implications of their actions in the event of a lockdown, they are forced to make a choice between their safety and hunger. Based on reports from media articles, labourers were stranded on borders with no water or food. Labourers who were working at a construction site stated that they have resorted to consuming water that is used for construction at their site for drinking purposes.[9] According to a report by Centre for Policy Research on the impact of the lockdown on daily wage labourers in Delhi, even the shutdown of informal safety nets such as religious institutions and street food donation drives for urban poor has been a disadvantage for these individuals.[10]

Fear of the implications of the virus on their health, insensitivity of the public, exploitative contractors, police brutality, and government apathy have compounded the already precarious existence of the migrant community in India.

[As the report observes]

The extensive media coverage of the mass movement of migrants, media reports along with concerns by activists and public has ensured that the centre and state move towards direct action now in addressing this issue. Across media reports, a similar statement is heard “Forget COVID, we will die of hunger first”. Migrants even before the spread of the pandemic have often been at risk of facing poor and unsafe living conditions especially within destination cities. The different factors which make their living conditions often vulnerable include overcrowding which could lead to transmission of infectious diseases, poor nutrition, quality of water, poor sanitation which could include accommodations lacking proper sanitation facilities[11]. In a country where public toilet coverage is dismal and poorly maintained, it is apparent that the ones on the move have no option than resorting to open defecation, and no means to follow the hygiene practises that would protect them from COVID infection.

Following are our recommendations.

- Central government should take the lead in coordinating with all states to ensure that there is parity in the economic relief measures that are being announced at State level and the disparities do not create new hierarchies of poverty and discrimination.

- Centre must ensure that essential ration provision is uniformly enforced across states: Unconditional support for rice, dal/pulses and salt. Our survey demonstrates 14% labourers do not have ration cards. Immediate measures must be taken by the Centre and States to provide them ration to prevent hunger deaths.

- Our database shows that around 94% of labourers do not have BOCW cards making them ineligible for any BOCW related benefit transfer. The status of these unregistered labourers remains precarious – if our dataset is representative of the 55 million labourers currently employed in the construction sector then more than 51 million labourers will not have access to any benefits. There must be immediate measures taken to bring the unregistered workers under the ambit of the Board, and to ensure they receive the benefit.

- Our research demonstrates that 17% of labourers do not have bank accounts: Immediately explore multiple options of ensuring economic benefits reach migrants on time – probably through flexibility in options of availing economic relief either through Jan Dhan accounts, Aadhar identification and cash payment at doorstep using Gram Panchayat and postal offices.

- Our survey shows that a staggering 42% of labourers mentioned that they had no ration left even for the day, let alone for the duration of the lockdown. PM CARES fund must be immediately utilised for income assistance to labourers taking into account the real loss in wages and the stipulated monthly minimum wages, for at least the next 3-6 months to prevent indebtedness or debt bondages, and consequent bonded/forced labour.

- 31% of workers mentioned they have loans and they will find it difficult to repay it without employment: Directives to be issued to banks to waive off loans of migrant labourers and to reschedule or waive off Self Help Group loans. Another directive addressing moneylenders, contractors and recruiters should be released asking them not to harass workers to repay debt and defer payments for the next 2-3 months.

- Unemployment allowance: Under both MNREGA as well as BOCW laws, there are provisions that allow for the state to pay for unemployment allowance MNREGA. Increase allocations from the Centre for the states to activate these respective provisions in the law, and announce these measures including detailed provisions of payment transfers from Centre to State to ensure that there is no delay in payments.

- The directive of the Central Ministry of Labour and Employment advised all public and private establishments to not terminate their employees, especially the casual or contractual labourers or reduce their wages: Our

surveys demonstrate 90% labourers (approx.) have already lost their source of income in the last 3 weeks. Centre should immediately institute a mechanism that monitors the job status or change in wages of the employees.

surveys demonstrate 90% labourers (approx.) have already lost their source of income in the last 3 weeks. Centre should immediately institute a mechanism that monitors the job status or change in wages of the employees. - Immediately, engage frontline health workers to identify and provide emergency support to pregnant women: In our survey, 328 workers mentioned that one of their immediate family members is pregnant. Further, half of these workers asked for immediate material support because they didn’t have enough ration to sustain for the week. Immediate support should be provided to them in the form of prenatal checks, medicines and appropriate nutrition.

- Our survey shows that 62% workers did not have any information about emergency welfare measures provided by the government and 37% workers did not know how to access the existing schemes. This is an important measure to mitigate the current status of fear and confusion: Reach out using online tools like Google Forms for surveys, social media communication and creation of credible IEC material for digital and physical circulation.

- The general practise of considering the male member of the family as the sole and default breadwinner, render female labourers belonging to the household invisible. It must be ensured that women labourers do not lose assistance they are entitled to, due to gender bias in counting.

*********

[1]N. S. S. O., 2010. NSS 64th ROUND (July 2007 – June 2008). [Online] Available at: http://mospi.nic.in/sites/default/files/publication_reports/533_final.pdf [2]Internal migration in India: A very moving story. [Online] Available at:https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/blogs/et-commentary/internal-migration-in-india-a-very-moving-story/ [3]Srivastava, R., 2012. National Workshop on Internal Migration and Human Development. [Online] Available at: http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/FIELD/New_Delhi/pdf/Internal_Migration_Workshop_-_Vol_2_07.pdf [4]Srivastava, R., 2012. National Workshop on Internal Migration and Human Development. [Online] Available at: http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/FIELD/New_Delhi/pdf/Internal_Migration_Workshop_-_Vol_2_07.pdf [5] TISS (2015) Inclusive Elections in India: A Study on Domestic Migration and Issues in Electoral Participation. Available online http://www.shram.org/reports_pdf/eci_report.pdf [6]Westcott, B. & Sur, P., 2020.Indian migrant workers could undermine the world's largest lockdown. [Online] Available at: https://edition.cnn.com/2020/03/27/india/coronavirus-covid-19-india-2703-intl-hnk/index.html [7]A guide to minimum wage in India in 2020. [Online] Available at:https://www.india-briefing.com/news/guide-minimum-wage-india-2020-19406.html/ [8]Anti Slavery International., 2017. Slavery in India's Brick Kilns & the Payment System. [Online] Available at: https://www.antislavery.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Slavery-In-Indias-Brick-Kilns-The-Payment-System.pdf [9]Frontline-The Hindu, 2020. Report highlights workers’ suffering during lockdown (Online) Available at https://frontline.thehindu.com/dispatches/article31183768.ece [10]Center for Policy Research, 2020. A Crisis of Hunger: A ground report on the repercussions of COVID-19 related lockdown on Delhi’s vulnerable populations (Online) Available at https://www.cprindia.org/research/reports/crisis-hunger-ground-report-repercussions-covid-19-related-lockdown-delhi%E2%80%99s-0 [11]Borhade, A., 2011. Migrant’s (Denied) access to health care in Ind. [Online] Available at: http://www.dishafoundation.ngo/projects/research-pdf/migration-and-health-in-india.pdf

Notes. --Excerpts from the report “Voices of The Invisible Citizens” prepared by Jan Sahas. --The Beacon wishes to acknowledge its gratitude to the team at Jan Sahas for this outstanding public service. And for allowing us to publish excerpts from it!

Leave a Reply